The Hidden Colonial Cemeteries of Oyster Bay

Some of the earliest burial grounds of New York State are to be found hidden away in this quaint town.

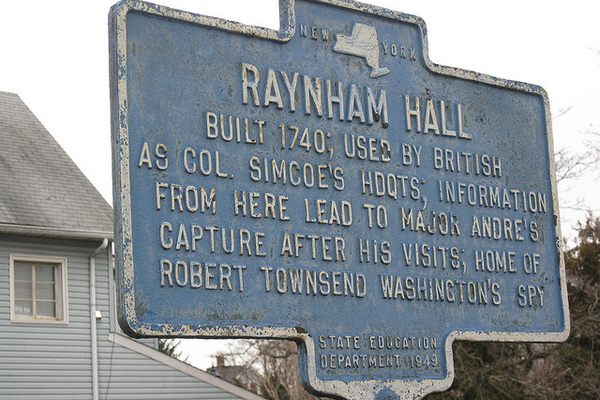

The quaint town of Oyster Bay, located on the north shore of Long Island, is steeped in history. The home of Theodore Roosevelt, it also played a vital part in George Washington’s spy ring during the Revolutionary War. But a large part of Oyster Bay’s history remains hidden from view.

Dotted around the town are numerous colonial era cemeteries, that as the town’s population has grown, have found themselves hidden away. Found at the end of small alleys running alongside private homes, or nestled behind driveways and surrounded by back gardens, visiting the cemeteries feels almost like trespassing, even though they remain open to the public.

Here are just three of them, along with directions about how to find these old burial grounds that are some of the oldest to be found in New York State.

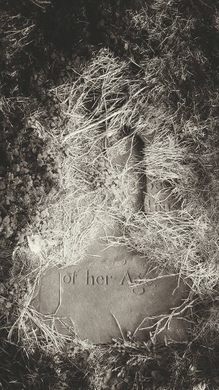

Running parallel to West Main Street, is Orchard Street. The idyllic small town charm of the wooden houses holds one such graveyard, the Old Baptist Cemetery. Surrounded by white picket fences and overlooked by bedrooms windows, is a burying ground that dates back to at least 1749, which is the earliest readable stone. Here the headstones often lie askew, some completely fallen over. One remarkable head stone, belonging to Mary, the wife of the town Reverend, Marmaduke Earl has been half consumed by a tree. Other residents of the forgotten burying ground include early members of the Townsend and Underhill families who dominated early colonial life in Oyster Bay.

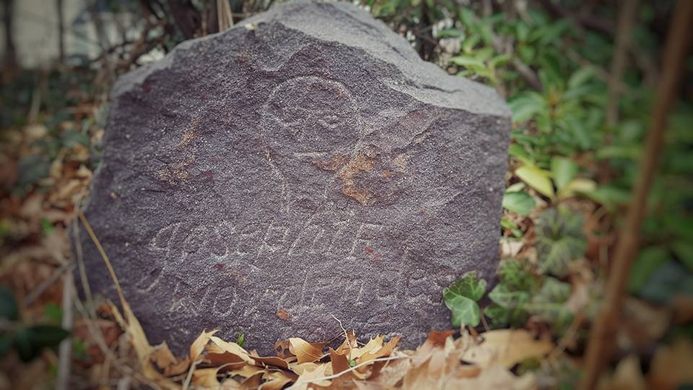

Traveling eastwards along East Main Street, turning left on McCouns Lane, and left again on Agnes Street, as the quiet road rises to the top of a hill, on the left hand side is a fenced plot of land. Again surrounded by houses, is a quiet, overgown burial ground, with many of the ancient tombstones covered in creeping undergrowth. Many of the headstones have deteriorated, making them hard to read. But the common colonial motifs — skulls, winged hour glasses, and the like — are still visible. This still place, covered in broken tree limbs and a carpet of leaves, rarely receives any visitors, the only sounds coming from the birds.

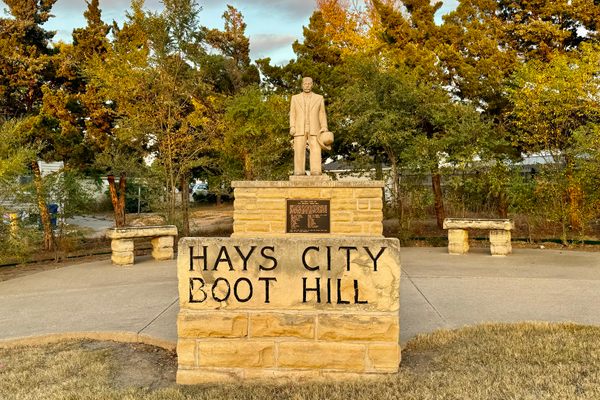

Then, hidden away at the end of Simcoe Street is perhaps the most important cemetery of all; the Fort Hill burying ground. Almost impossible to find, access is gained by approaching the last house on the right. Walking down a narrow unpaved trail running alongside a fine wooden home, is a chained, rusted gate, closed by an openable bolt. One of the earliest graves here dates to 1668, belonging to John Townsend, a local wealthy merchant. Most remarkably, here also lies Robert Townsend, who operated under the code name “Culper Junior” in General Washington’s spy service. He was instrumental in uncovering the Benedict Arnold and Major John André plot to surrender West Point to the British army.

This deteriorating ancient graveyard is surrounded on all sides by more back gardens, filled with children’s toys, flower beds and swimming pools. It is also home to a daughter of the Townsend household, Sarah, also known as Sally, sister to Robert. Sarah Townsend is remarkable in that she received what is said to be the first Valentine’s Card given in America.

The hidden cemeteries of Oyster Bay appear to have received little by way of maintenance, and have just become a forgotten part of the town. But it appears that this has always been the case. One Samuel Youngs wrote of the difficulty in tracking down the early colonial graves in a poem from the early 1800s:

Where are the stones that mark the bones

Of those who die in Oyster Bay?

There are no stones to mark the bones

Of those who die in Oyster Bay.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook