The Rufus Stone

A stone, covered in metal, commemorating an event that happened somewhere else a thousand years ago.

William Rufus loved hunting. Really loved hunting. He would have been more than happy to have spent all day, every day tearing after game through the forests of England. This was just as well really, as much of England had been turned into a giant playground for the Norman nobility that had assumed control of the country after the 1066 invasion.

One of the first things that Rufus’s father, William I, also known as William the Conqueror, did upon seizing the throne after the Battle of Hastings in 1066, was to declare vast tracts of land as “forest.” This did not mean the same thing as it does today. Those forests were huge areas of trees and open scrubland—the perfect environment for deer. Only Norman nobility was allowed to do very much of anything in the forests, which preserved them as vast playgrounds for the elite, and there were stiff penalties for anyone caught doing something that they shouldn’t, which usually involved having something cut off. The jewel in the crown was undoubtedly the New Forest in southern Hampshire.

Rufus was the third son of the first Norman king, and given the name “Rufus,” or “The Red,” probably because of red hair or a ruddy complexion, though no likenesses of him survive from the period. The brothers had famously tempestuous relationships with each other and with their father, and were often inclined to declare war on each other. Indeed, the king died from injuries sustained while besieging his eldest son, Robert Curthose. Curthouse inherited the plum prize of Normandy, while Rufus was given the less coveted sovereignty of England. As the third son, he would not have been given such a prize had not his middle brother been killed in, yes, a hunting accident in, you guessed it, the New Forest.

William II, as Rufus was known, was not a popular king. Any Norman would have been unpopular with the Anglo-Saxons, but he was also unpopular with his own people and, most importantly, with the Church, though he was a fair king with regard to war and diplomacy. Perhaps most importantly, William II failed in his most important duty as a medieval monarch: siring a son to succeed him. He appears to have neither married, nor taken a mistress, which led to accusations of homosexuality.

His unpopularity with his own people meant that the events of the August 2, 1100, would always to be mired in suspicion. William II and his entourage went into New Forest to engage in his favorite pastime, hunting. It seemed that a particularly fine stag became their quarry, and one of the king’s henchmen, a French noble named Walter Tyrell, famed as the hunting party’s best archer, took shot at it. The arrow, it is said, completely missed its mark, ricocheted off of an oak tree, and punctured the king’s lung, killing him. In apparent disarray, everyone left the king’s body where it fell, and Tyrell hightailed it back to France to escape repercussions (there were none, as no one was particularly upset). The body was recovered by a local charcoal burner named Purkis, who took the dead monarch in his cart to Winchester, where a low-key burial took place in the cathedral. William II’s younger brother Henry seems to have been particularly delighted by his brother’s termination. Quick as a wink, and before anyone could complain, he went to Winchester and had himself crowned King Henry I, even though there were no archbishops present.

Rumors began to circulate as to what had happened in the forest.

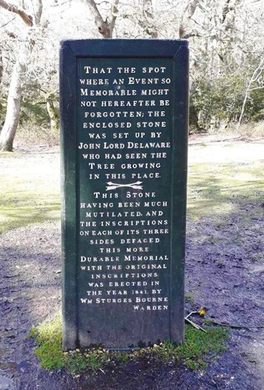

The Rufus Stone was erected in the late 18th century, some time after King Charles II had been shown “the tree” from which the fatal arrow glanced. Except, it wasn’t the actual tree, and historians are in broad agreement that the “accident” had happened somewhere on the Beaulieu Estate, some miles away. The tree shown to Charles II was then cut down and burnt, and a monument erected. Originally about 5 feet-10 inches tall, surmounted by a stone ball. In 1789, another royal visit by King George and Queen Charlotte led to an inscription being added:

“Here stood the Oak Tree, on which an arrow shot by Sir Walter Tyrrell at a Stag, glanced and struck King William the second, surnamed Rufus, on the breast, of which he instantly died, on the second day of August, anno 1100.

That the spot where an Event so Memorable might not hereafter be forgotten; the enclosed stone was set up by John Lord Delaware who had seen the Tree growing in this place. This Stone having been much mutilated, and the inscriptions on each of its three sides defaced, this more Durable Memorial, with the original inscriptions, was erected in the year 1841, by Wm [William] Sturges Bourne Warden.

King William the second, surnamed Rufus being slain, as before related, was laid in a cart, belonging to one Purkis,[e] and drawn from hence, to Winchester, and buried in the Cathedral Church, of that City.”

In 1841, a cast iron cover was placed over the stone, as it had been vandalized. So the stone was no longer really a stone. An oak tree still stands nearby, perhaps grown from an acorn of the tree shown to Charles II.

Only a bowshot away is the Walter Tyrell Public House, named after the man who rather unfortunately shot the King—somewhere else. It all still leaves the question of whether it was an accident or an act of filial regicide.

Know Before You Go

Parking at the Rufus Stone car park is free, and the stone is a very short walk away across the public road. It is accessible at all hours.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook