AO Edited

Valley of 10,000 Smokes

In 1912, this idyllic Alaska landscape was blown apart in the largest volcanic eruption of the 20th century.

The trees warn you of what’s ahead. When you start out on the 20-plus miles of single-lane gravel road, by foot or National Park Service bus, the spruce crowd in on either side, many as tall as a four-story building. The further you travel along the road from Katmai National Park’s Brooks Camp Visitor Center, the shorter the trees, with more and more open space between them. By the time you crest the final hill, only a few spruce, pint-sized and slender, grow between wide spreads of fireweed and lichen.

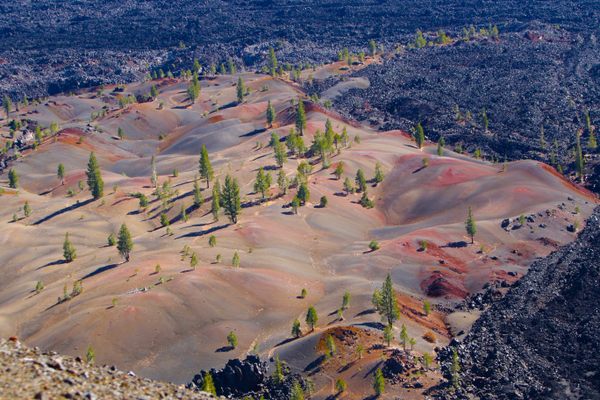

At the top of the hill, looking to the southeast, you begin to understand why. Before you, a broad, flat valley fills the space between dark mountains, their summits hidden behind clouds. The black rock of the peaks is a sharp contrast to the valley floor’s desert colors. Its pale yellows and pinks are broken up only by the wiggling lines of deep, narrow canyons, carved by meltwater rivers over the past century.

Nothing in the valley is more than 110 years old. Whatever stood here before then was obliterated in 1912 during the most powerful volcanic eruption of the 20th century.

The Novarupta event, which unfolded over several days beginning June 6, blew apart mountains. Pyroclastic flows of lava, ash, and superhot gas hurtled through the original valley at more than 100 mph, incinerating everything in their path. By the time it was over, the eruption had expelled three cubic miles of magma. For comparison, 1883’s Krakatau eruption, considered one of the world’s most powerful, released 2.2 cubic miles, and the Mt. St. Helens eruption of 1980 just 0.1 cubic mile.

Novarupta changed the global climate, cooling the Northern Hemisphere by about 2 degrees Fahrenheit for months afterward. And it changed this corner of southwestern Alaska forever: The pastel-colored valley floor visible today is actually ash from the 1912 eruption, dumped several hundred feet thick in places.

Visitors expecting to see 10,000 thin lines of smoke snaking upward from the pale ash layer will, however, be disappointed. The name was coined in 1916 by botanist Robert Griggs, one of the first people to visit the area following the eruption. At the time, the earth was still seething, the valley floor dotted with scores of steam vents, which have since died out. The eruption was considered scientifically significant enough that, two years later in 1918, President Woodrow Wilson declared the roughly 50-square-mile valley and its surroundings as Katmai National Monument. The monument expanded over time and was eventually designated as a national park in 1980.

In the century-plus since the eruption, the valley in general has become a more hospitable place. White spruce, its seeds spread by the wind, has begun to reestablish itself. Wolves, brown bears, caribou, and even lynx frequent the area. One species that has not returned, at least not permanently, is our own. Two Alutiiq/Supiaq villages near the valley were abandoned as the eruption unfolded, their residents dispersed to nearby Kodiak Island and elsewhere along the Alaska Peninsula. Novarupta also ended the use of a traditional trade route that ran through nearby Katmai Pass.

Know Before You Go

To access the Valley of 10,000 Smokes, visitors arrive by floatplane or water taxi to Brooks Camp, 23 miles to the northwest, and attend a mandatory bear safety orientation at the visitor center. From there, you can hike along the road or take a bus, part of a ranger-led day trip that runs daily June-September and must be booked in advance. There is an exhibit on the Novarupta event of 1912 at the Robert F. Griggs Visitor Center, overlooking the valley at the road’s end, and a handful of day hike options from there.

The views from the visitor center are stunning, but to see the Novarupta lava dome, which marks the epicenter of the eruption, you need to backcountry hike several miles deeper into the valley. There are numerous potential routes to the lava dome, but all of them take at least two days and involve hazardous river crossings. Backcountry campers must carry their food in bear-resistant containers.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook