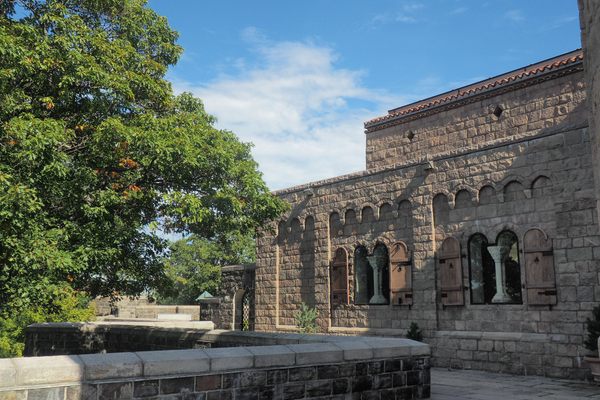

Van Gelder Studio

Hundreds of iconic jazz records were made in this church-like space.

As a teenage jazz fan growing up in New Jersey, Rudy Van Gelder would head all the way into New York to hear the musicians he loved. By the time he was 20, they were coming to him instead. An optometrist by trade, Van Gelder spent evenings and weekends recording musicians in a studio in his parents’ living room in Hackensack. By the end of 1954, so many hits had been cut there—and so many record jacket photos taken—that jazz fans the world over were “familiar with the curtains in the Van Gelder living room,” as the historian Ira Gitler once wrote.

In 1959, Van Gelder quit his day job and moved himself and his equipment to a house in Englewood Cliffs, where he built a new studio. The space, designed by an acolyte of Frank Lloyd Wright’s, was “high-domed, wooden-beamed, brick-tiled,” spare, and modern, with 39-foot ceilings, Gitler wrote. More than one musician compared it to a chapel or cathedral—an impression underscored by the fact that so many greats came to record there, including John Coltrane, Herbie Hancock, and Art Blakey. Coltrane’s recently discovered “lost” record, Both Directions at Once, was recorded at Van Gelder Studios on March 6, 1963.

In his recordings, Van Gelder was committed to capturing the warmth and intimacy of live jazz. “My goal is to make musicians sound the way they want to be heard,” he once told the New York Times. “Someone wanted to put a man on the moon, but it was an engineer who got him there.” His process was meticulous, and the particulars of it were closely guarded: according to historian David Simons, if someone took a photograph in his studio, he’d move the microphones around first so that no one could steal his secrets.

He had more esoteric tactics, too. One day in September of 1991, the saxophonist Joe Henderson was recording by himself, and requested that Van Gelder dim the lights. “How about no lights,” Van Gelder reportedly replied, before plunging the whole studio into darkness. The song that followed became the title track of Lush Life, and won Henderson a Grammy for “Best Jazz Instrumental Performance” in 1992.

Van Gelder died in 2016, at age 91, and left his home and studio to his longtime assistant, Maureen Sickler. She and her husband still record bands in the space—although, she says, it’s less busy than it used to be.

Know Before You Go

For information about visiting the site, contact Maureen Sickler at [email protected].

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook