America’s Largest Outdoor Theatre Event Features 700 Lip Syncing Mormons

The annual Hill Cumorah Pageant is the real Book of Mormon.

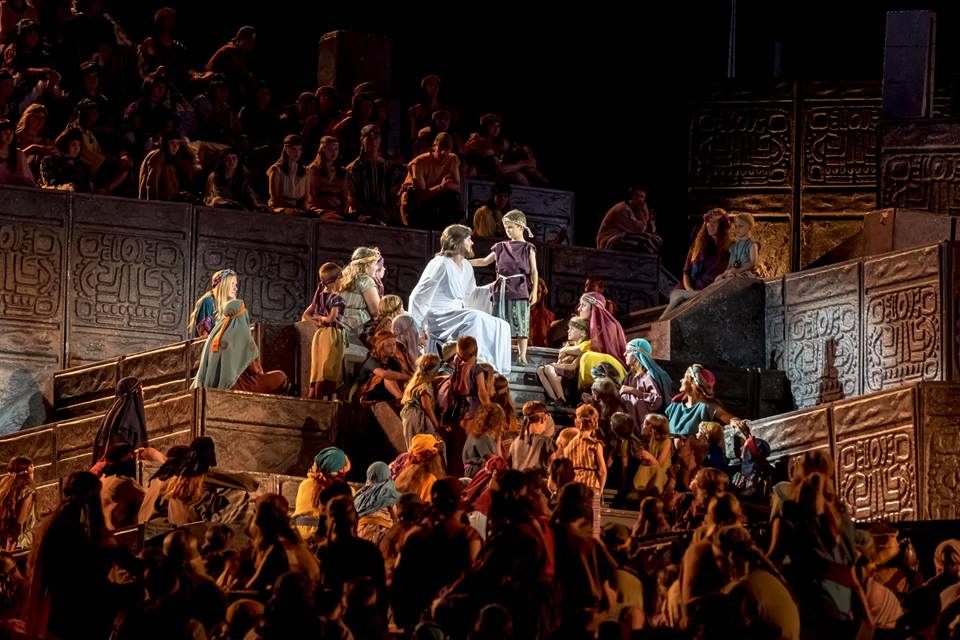

Opening night of the 2016 Hill Cumorah Pageant. (Photo: Courtesy Hill Cumorah Pageant)

“It’s better than Disney World,” said Kelsey Trainor, standing in a field in upstate New York, surrounded by 700 costumed Mormons.

All around were throngs of missionaries and tourists. People took photos in front of a seven-tiered stage, and families staked out seats among rows of green plastic chairs. Children walked around in the grass, dressed as the sinners of an ancient Mesoamerican civilization. Out on the highway, protestors shouted into bullhorns.

Kelsey and her four friends had driven up from Virginia in a chartered bus. It was the middle of July, and the bus did not have air-conditioning. Nevertheless, the young women were in good spirits. They had met some of their favorite prophets. Also, they had just taken a photo with Joseph Smith.

“It’s a little bit overwhelming,” says Teresa Weigeshoff, one of Trainor’s buddies.

Each summer, some 900 members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints gather in rural New York. There, on a sacred hillside, they reenact key scenes from the Book of Mormon.

The Hill Cumorah Pageant is an elaborate production—possibly the largest annual outdoor theatrical production in the United States—yet most of the world has no idea that it exists. It has taken place since 1937. The current version, with a script by science fiction novelist Orson Scott Card (Ender’s Game), debuted in 1988. The exact number of participants changes annually, and this year’s pageant included 744 actors, 150 crew members, and nine directors. The show involves water cannons and jets of fire. A spotlight representing the Star of Bethlehem is so powerful that its use requires annual approval from the FAA.

According to the Church, this part of New York was the site of a civilization-ending battle around 400 C.E. That was just a few centuries after Mormons believe that Jesus visited the Americas, and 800 years after an Israelite prophet named Lehi left Jerusalem and sailed to the New World.

Mormons believe that this is also the spot where a 21 year-old farmer named Joseph Smith dug up a set of inscribed golden plates in 1827. Using a sacred stone in a hat, he translated the inscriptions into English and published them as the Book of Mormon.

If you’re a believer, the Book of Mormon is scripture, on par with the Old and New Testaments. If you’re a skeptic, the Book of Mormon is a kind of extraordinary Biblical fan-fiction—a book that takes figures and themes from the Christian Bible, inflects them with an American vibe (Mormon prophets talk a lot about freedom and “the voice of the people”), and then sets the whole story in the familiar Promised Land of the Americas.

For many, then, this corner of New York has a certain magnetism. Most American Mormons now live in the West, but thousands volunteer each year to take part in the Pageant—not everyone gets a slot—and thousands more travel to the town of Palmyra to see the show, along with plenty of non-Mormons.

For such an extravagant production, the casting is pretty casual. You don’t need any acting experience to appear in the Hill Cumorah Pageant. You won’t get paid. You do need to be a Mormon, and if you’re employed, you do need to take three weeks off from work. Roles are reassigned each year, even for returning actors. When the cast arrives in Palmyra a week before opening night, the directors line them up in the amphitheater and quickly start handing out parts. Within a few hours, they have filled the show’s 1,200 roles (most actors are double-cast).

The 2016 Hill Cumorah Pageant. (Photo: Courtesy Hill Cumorah Pageant)

Because the whole pageant is sound-tracked—the actors are lip-syncing—and because it’s hard to read facial expressions from so far—the stage is huge—the job mostly involves hitting your mark, gesturing impressively, and trying not to accidentally whack anyone with a fake spear.

Backstage, the vibe feels like a summer camp. Entire families appear in the show together. At the foot of the hill where Smith found the Golden Plates, cast members park RVs, hook up outdoor refrigerators, and set up grills. “You know, the little ones, they like to pile on. They just sleep on the floor, they do whatever. We make it work,” says Joshua Boswell, who plays the prophet Alma, about the RV in which he’s staying with his wife and nine of their eleven children.

A Pageant volunteeer, Heather Williams, gave me a backstage tour. In one of the seven dressing rooms, we walked past racks of tunics and plastic tubs full of bangles. In a shed, the prop master showed us a large vase—he and his daughter found it at Pier 1 Imports—that had been repackaged as exotic booty from an ancient battle.

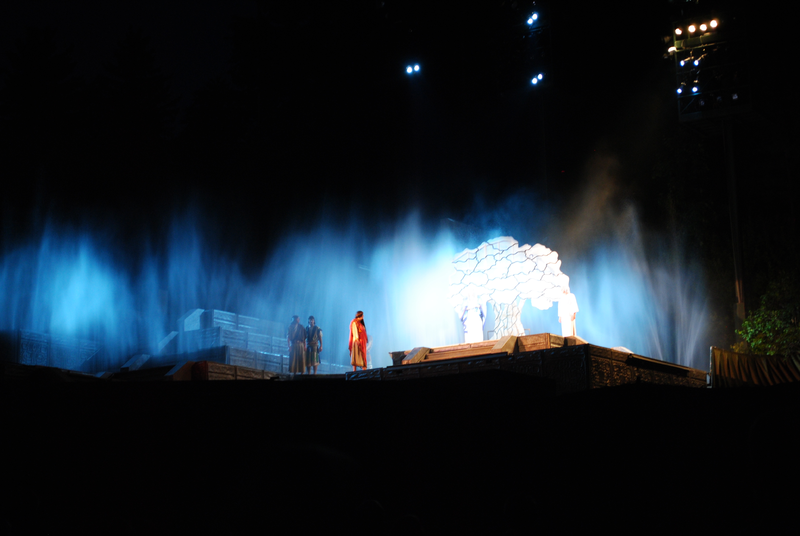

At the Hill Cumorah Pageant, a depiction of Nephi’s vision of Lehi’s dream. (Photo: Eustress/CC BY-SA 3.0)

As we left the building where they keep the fake beards (and some of the nicer wigs), Williams steered the conversation in a more solemn direction. “We truly believe that angels and prophets walked this ground,” she says. Williams is a local. Raised in the Church, she decided to commit fully to Mormon life as a teenager, after praying in a nearby grove sacred to the Church. She felt an enormous sense of peace, she remembers—a sense that has recurred throughout her life.

The Pageant stage is an enormous scaffolded affair, clad in vacu-formed plastic to look like a Mesoamerican temple. Williams waited on a lower tier while I climbed a metal ladder to the stage’s highest point. Later, a 20 year-old first-time actor, cast in the role of the Jesus, would appear on this spot, his white robes incandescent in the spotlights. For now, the amphitheater was empty, and everything was hot. The thousands of green chairs in the grass below looked tiny. I tried to imagine what it would be like to climb up here and impersonate Jesus.

“Where you’re standing is where I found out that I was pregnant with my seventh child,” Williams says suddenly. She had a moment of dizziness and sudden nausea years before, there are the top of the stage.

Several months later, a child was born.

A scene from the Hill Cumorah Pageant in Palmyra, New York. (Photo: Krishna Kumar/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Tensions lurk around the edges of the Hill Cumorah Pageant. Protestors—generally Christians who believe that Mormons are heretics—regularly visit, re-enacting the kind of theological throwdown that originally drove early Mormons out of the hills of upstate New York. Security around the stage is tight. A local business owner told me that, over the years, he’d heard shouting matches between Mormons and protestors in the streets.

There are also questions of race and appropriation. The Pageant’s cast is almost entirely white; the people they depict are almost uniformly not. It can be uncomfortable to see white men in faux-Mesoamerican headdresses. When I brought this issue up with Brent Hansen, the Pageant’s head director, he argues that I was thinking too much like a non-Mormon. “We back off to a large extent in this production from that whole concept of Native Americans,” he says. “Native Americans came after these people. These people who moved out Jerusalem, they built a culture here, and so it’s simpler, in a lot of ways, because we dodge a lot of issues that aren’t issues in the story that we’re trying to tell.”

The show itself taps into the peculiar thrill evoked by Broadway musicals, marching bands, and perhaps even North Korean martial exercises—that feeling of watching the well-synced motion of human beings and music. The tides of cast members ebb and flow across the stage. They fight. They run. At times, they dramatically perish. Prophets get up on platforms to lip-sync their speeches.

The real show is before the show, when the audience mingles with the cast. Gregory Thornton—a hedge fund manager from Fort Collins, Colorado, cast in the role of Joseph Smith—talks about the affection he receives when he’s roaming around in costume. “Since I’m representing Joseph, you get to see their love and appreciation for Joseph,” he says. “I’m just playing a role—like Mickey Mouse, right?—but it’s fun to see how excited [they get].”

Wandering around the American-Biblical-Renaissance Fair, you feel how thin the lines are between theater and ritual, play and worship, the mythic and the kitsch.

Preparing for the dress rehearsal. (Photo: Courtesy Hill Cumorah Pageant)

It was somewhere in these borderlands between Disney and Jerusalem that I found Kelsey Trainor and her friends, who were trying to process the experience of seeing scripture come to life.

“I definitely did not picture Nephi to look like that,” says Trainor, referring to a key Mormon prophet and his descendants. “I thought every Nephite would be like AWRAOHRR,” she adds, making a series of guttural, manly noises.

“Well they were, like, 14 year-old boys!” protests Emily Gingerich.

Soon there were screams. In my notes and audio recording at this point, the cross-talk becomes almost indecipherable.

“I think that’s him.”

“That’s Noah.”

“KING NOAH!”

“Wait, how do you know that’s King Noah?” I ask.

“Because someone—”

“—we asked someone—”

“—and a Nephite told us.”

“And described his outfit.”

“We just go and ask, like, ‘What does Nephi look like?’ And then we go find him.”

“KING NOAH!” screams Kelsey.

“He’s too far away. He’s talking to people.”

A minute later, duly summoned, King Noah walks over. He is a young man wearing a spiky red and blue headdress and a fake goatee that reached to his collarbones. If you imagine how a 1950s film director might depict the Aztec emperor Montezuma, you will have a good sense of the overall aesthetic.

“Are you King Noah?” someone asks.

“I am King Noah,” says King Noah.

“Holy crap, he’s huge!” says Teresa Weigeshoff, who is 4’11”.

The actor playing King Noah gives his height as 6’4” or 6’5”.

Weigeshoff went up to stand with him. Behind them was the stage and the steep tilt of Hill Cumorah. On the top the hill stands a golden statue of the angel Moroni, not far from an enormous American flag.

Down on the grass, Weigeshoff and the king posed for a photo. The show, on and off stage, kept going on.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook