How a Football Team Became Mascots for Vegetarianism

In 1907, a championship squad changed what it meant to eat meat-free.

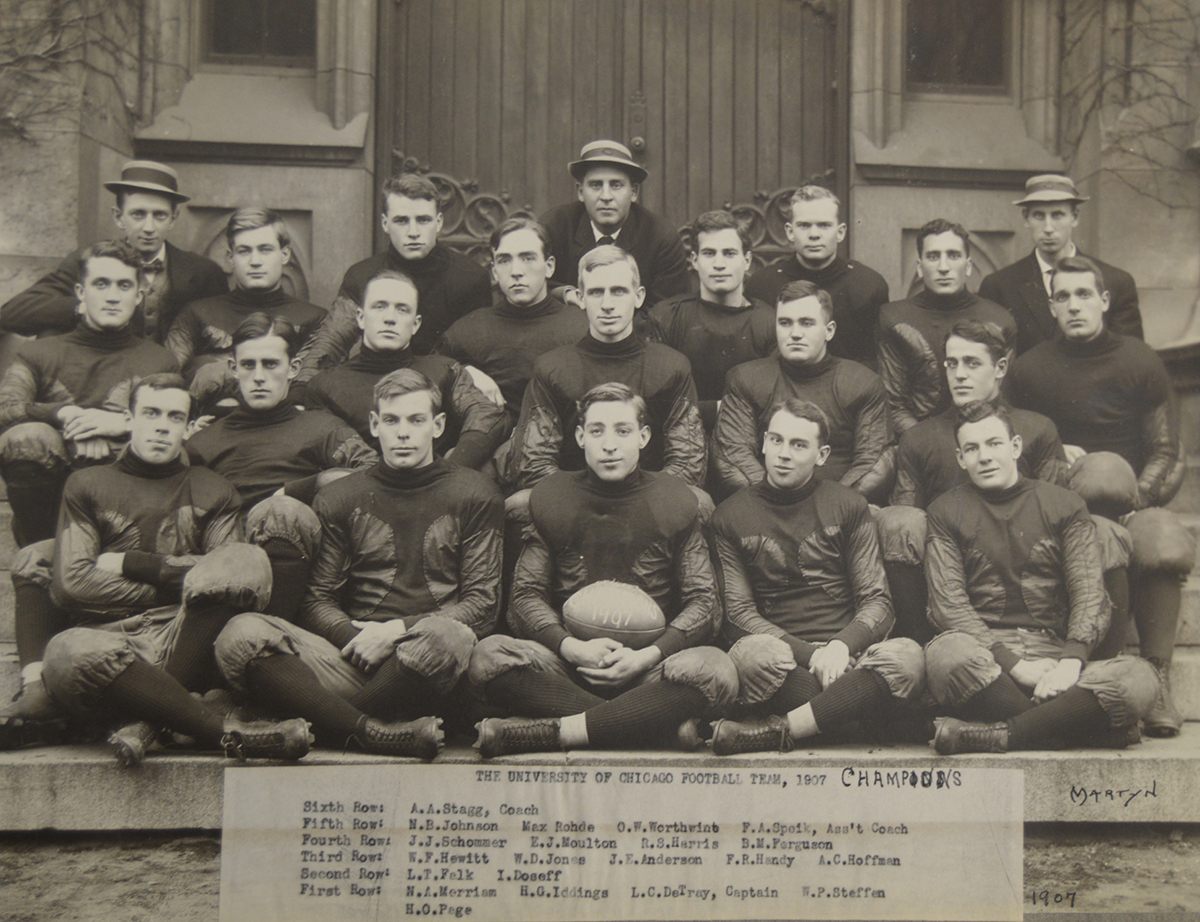

As Coach Amos Alonzo Stagg limped out onto the University of Chicago’s Marshall Field for the first day of fall football training in 1907, he had no shortage of strategies to carry his Maroons to the championship. For summer reading, he had required every player to memorize the new rulebook (football was a fast-evolving sport). He’d planned an exhausting circus of novel drills. And tight under his arm, he held a notebook bursting with top-secret new plays.

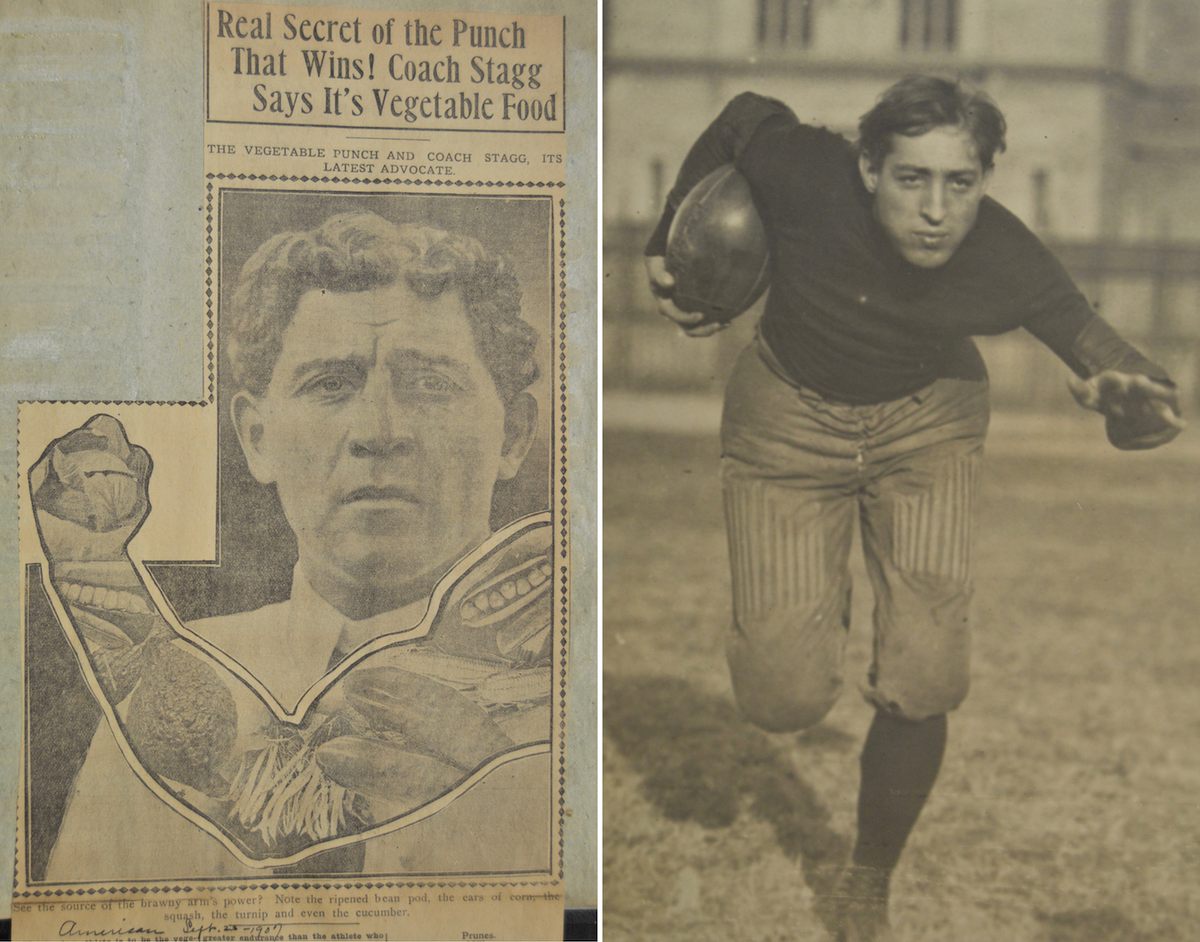

Fans across the nation, having watched in awe as the Maroons clinched a perfect-record Western Conference victory in 1905, expected nothing less of the renowned coach. But one of Stagg’s strategies took everyone by surprise: For the 1907 season, he was putting his team on an all-vegetarian diet, the same one he himself had followed for nearly two years.

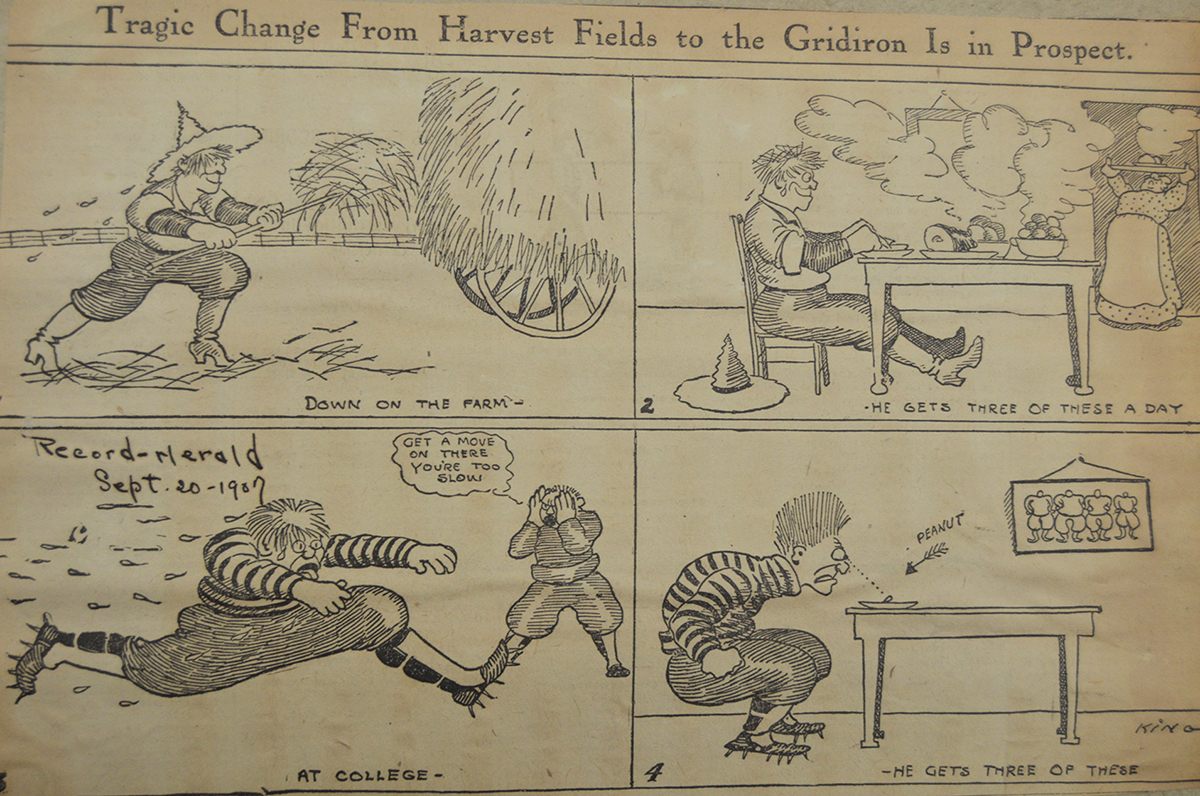

“Vegetarians Only,” sneered the Boston Globe. “Vegetable Football,” quipped a wire story carried in smaller rags. Most hometown newspapers offered a fuller menu: The Chicago Inter-Ocean wrote, “Dried Apples, Prunes, Nuts, and Water for Maroon Team,” while the Tribune declared “Kickers to Train on Squash.”

No newsman mined the story for mirth more than the Tribune’s new sportswriter, a former Maroon himself. Walter “Eckie” Eckersall, the bad-boy superstar quarterback who had been extravagantly mourned during his final season in 1906 (then quietly expelled) gave the Maroons their mocking new moniker: the Vegetarians.

The “training table” (a mandatory diet and dining regimen) had recently been banned, over Stagg’s vocal objection, for most teams in the Maroons’ conference. So officially speaking, vegetarianism was only a “suggestion.” But Stagg, who had long insisted on abstinence from smoking, drinking, and cursing, enjoyed fierce loyalty from his squad, which meant, as one paper put it, “his suggestions are law.”

Captain Leo DeTray, an eager halfback whose on-field injury in 1905 had left him half-blind in one eye, had already followed Stagg’s lead by going partially vegetarian to treat indigestion, and was busy converting teammates. He insisted that red meat, the traditional football training diet, was the cause of rough play, and reminded the scholars that Plato and Pythagoras had abstained from flesh before them. Whether eagerly or begrudgingly, players and assistant coaches went on record to embrace “squirrel food.” The only naysayer, who groused that he didn’t “see the use of having teeth if we can’t eat meat,” failed to make the final roster.

When they became the Vegetarians, the Maroons also became standard-bearers for a fledgling (Chicago-based) meat-free philosophy. “It has been proved very conclusively that under certain types of muscular strain, the non-flesh-eater shows far greater endurance than the athlete who eats flesh,” Stagg told one newspaper. For vegetarians everywhere, and the meat-eaters who mocked them as listless and weak, this was a throw-down: Chicago’s upcoming season would prove—or not—the superiority of a non-meat diet.

Some insiders suggested that, since none of the Maroons’ four Western Conference games were against archrivals Wisconsin and Michigan, Stagg’s challenge might prove too easy. A few skeptics noted that a mere two-month change in diet was unlikely to make any measurable physical difference, which meant the challenge was a folly. But most simply wondered why Stagg had issued it at all. What was a football coach doing giving up meat?

In the Staggs’ poor West Orange, New Jersey, household, the autumnal slaughter of two fattened hogs made most family members drool for hams and sausages, but not young Lonnie. It wasn’t that he had ethical or dietary objections; rather, he was focused on a more immediate joy: the animals’ bladders, which, once blown up with a hollow quill, could be tossed, kicked, and run around with as long as they held air. Pigskins, he would later write, “were the only footballs we knew.”

While on scholarship and a penny-stretching starvation diet at Yale’s divinity school, Stagg’s love and mastery of sports steadily tugged him away from theology, until he gave up the cloth altogether. Nonetheless, asceticism and a strict moral code remained forever central to his approach. As Director of Physical Culture at University of Chicago (where he also coached baseball and track), he was credited not just for bringing professionalism to coaching and major innovations to the play of football, but also for his commitment to athletics as an integral element of character-building and moral uplift.

A decade into his stint at Chicago, though, Stagg’s sports zeal caught up with him. Rebounding too soon from a football-induced bout of pneumonia in the winter of 1904, he slipped on a patch of ice after track practice, dislocating vertebrae and pinching his sciatic nerve. “Arrogant in my strength,” he recalled, Stagg ignored the pain and coached a full season of track and baseball, before hobbling away for treatment. From Colorado to Indiana to Miami, Stagg spent the next two decades of vacation-time—and all of the family savings—at a succession of sanitariums (health and wellness resorts) trying to heal. During football season, when walking was too painful, he used a bike to race up and down the sidelines; later, he rode in a motorcycle sidecar and then a car. By 1907, at age 45, he had grown used to his players’ affectionate nickname: “the old man.”

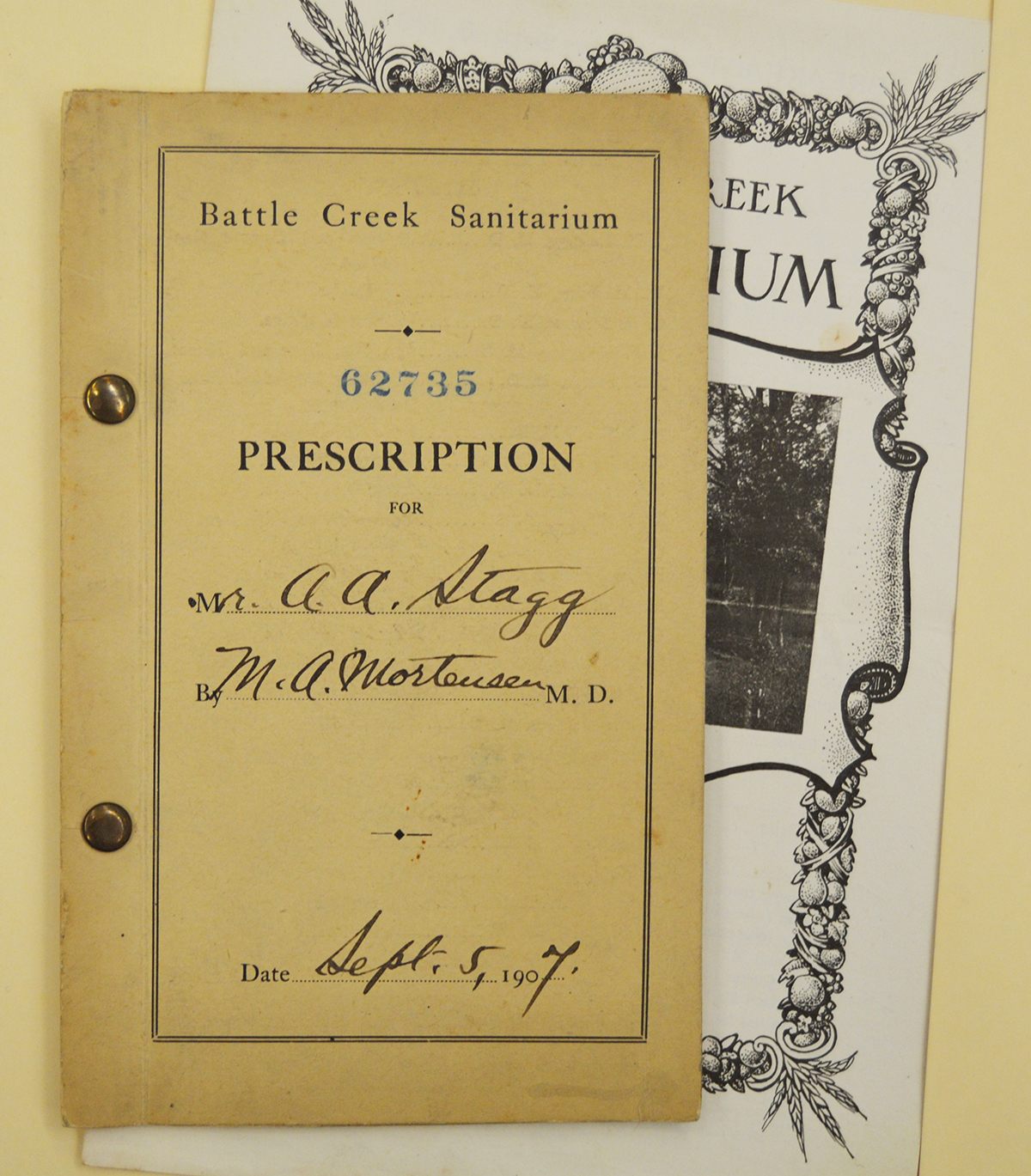

That September, a month before football training, Stagg checked into Michigan’s world-famous Battle Creek Sanitarium. Owned by the staunchly vegetarian Seventh Day Adventists and run by health-activist J.H. Kellogg, Battle Creek was more than just a spa; it was the hub of an international, meat-free, wellness-and-nutrition empire.

The “Battle Creek Idea,” as evinced in the booklets and menus that Stagg marked up and brought home, was a hodgepodge of turn-of-the-century physical therapy and dietetics, common sense wisdom gussied up as science, and technological gimmickry. After his daily full massage, it was on to “Swedish movements” and arm exercises, 90 seconds on the slow-shaking machine, two minutes at the foot drum, and a whole lot of vibrator action on the spine and abdomen. Also on the agenda: “rational hydrotherapy” (plunges, douches, and wet-wraps) and the “out-of-door method” (fresh air).

As for food, since Stagg’s physical ailments had been attributed to “super-acidity” (the sciatica diagnosis came later), he stuck to Battle Creek’s “anti-toxic” diet. For breakfasts, he ate grapefruit, blueberries, toasted corn or rice, and a biscuit of “granose” (pressed wheat). For one dinner, he chose cream of corn and nut and rice croquettes. But nuttolene with mint sauce and chipped protose in cream—Kellogg’s early experiments in fake meat—were apparently too exotic for Stagg’s palate.

What really impressed Stagg at Battle Creek, though, was a record-breaking show of meatless strength. One afternoon, as he and other guests watched in awe, a vegetarian medical student named John Granger performed 5,002 squats in 139 minutes. Just three weeks earlier, Granger had out-squatted a meat-eater in a match-up organized by Irving Fisher, a Yale economist-cum-vegetarian activist who orchestrated these demonstrations for years. “I saw [Granger] do it 2,000 times,” Stagg gushed, “then I had to exercise myself while he did it 3,000 times more.” The old man was sold.

On the eve of their first game, the Maroons hosted an on-campus “purity banquet” for the visiting Indiana team, a tradition inaugurated by Stagg to encourage gentlemanly fellowship between opponents. With the coach’s post-Battle Creek mantra echoing in their ears (“A man’s food should be one-tenth [proteins], four-tenths fats, and the rest carbohydrates”), the Vegetarians suffered through their cream of tomato soup, celery, creamed spinach, and potatoes, and drooled across the table as the Hoosiers wolfed down beef and trout. Though “a craving for a slice of beef is sometimes evident,” Eckie wrote in the Tribune, “the Maroon leader crushes such desires.”

The next day, on the field, the meat-free diet spawned a new cheer:

“Sweet potatoes, rutabagas, sauerkraut, squash!

Run your legs off, Cap’n De Tray!

Sure, our milk fed men, by gosh!

Will lick ’em bad today!”

Despite their gleeful chants, Maroons fans had no idea what to expect, and not just because their team had gone meatless—they were playing a brand new game. Major rules changes in 1906 decisively severed the sport from its roots in rugby, turning the game into a perpetual scramble for ball possession and short yardage gains. This style of play looks familiar to today’s fans of American football, but at the time, confounded critics denounced it as utter chaos.

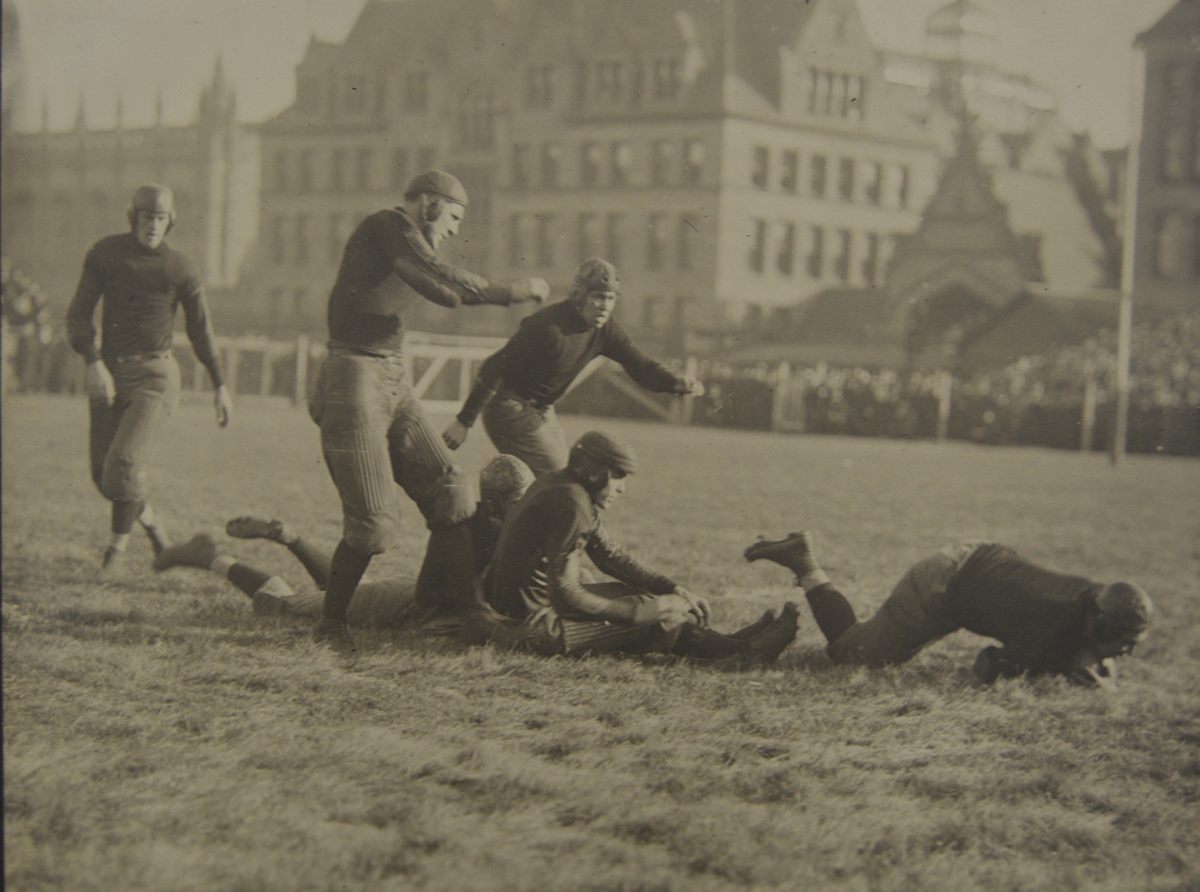

From the start of play, it was clear that Stagg’s team was anything but confused. They made liberal use of the novel forward pass, and quarterback Wallie Steffens (Eckersall’s replacement) bobbed, weaved, and sprinted to touchdown after touchdown. The Vegetarians played a far nimbler and smarter game than the Hoosiers in a 27-6 victory.

A week later, at Illinois, their game only got better. They were now, as the Inter-Urban put it, a “machine,” led by “fleet and agile Steffen” and “plugging, dodging DeTray,” who “played one of the best games of his great career.” With a 42-6 victory, the only obstacle standing between the Vegetarians and a championship (awarded simply to the team with the best record) was the Minnesota Gophers.

Teased the Tribune later in the month: “When the herbivorous Maroons meet the carnivorous Gophers next week, will it be a case of rolled oats or mince meat?” That question mattered most of all for one very particular group of Chicago fans.

At the turn of the century, Chicago was the nation’s unrivaled capital of industrialized meat production. Its epicenter was a sprawl of stockyards, slaughterhouses, and packing plants known as the Yards, which “processed” over 400,000 animals a day. In 1906, Upton Sinclair had exposed the horrors of the Yards in The Jungle, which he intended as a rallying cry against dangerous working conditions, but instead sparked federal legislation to clean up the nation’s meat supply. “I aimed for the public’s heart,” he later recalled, “and by accident hit it in the stomach.”

But the Yards had already been hitting Chicagoans—particularly South Siders—in the nose for decades. When the winds blew just right, not even leafy Hyde Park and the University of Chicago, a few miles southeast, were safe from the stench: a seismic olfactory assault of waste, chemicals, and rotting flesh. Unsurprisingly, Chicago was simultaneously home to the fastest-growing meat-free community in the nation.

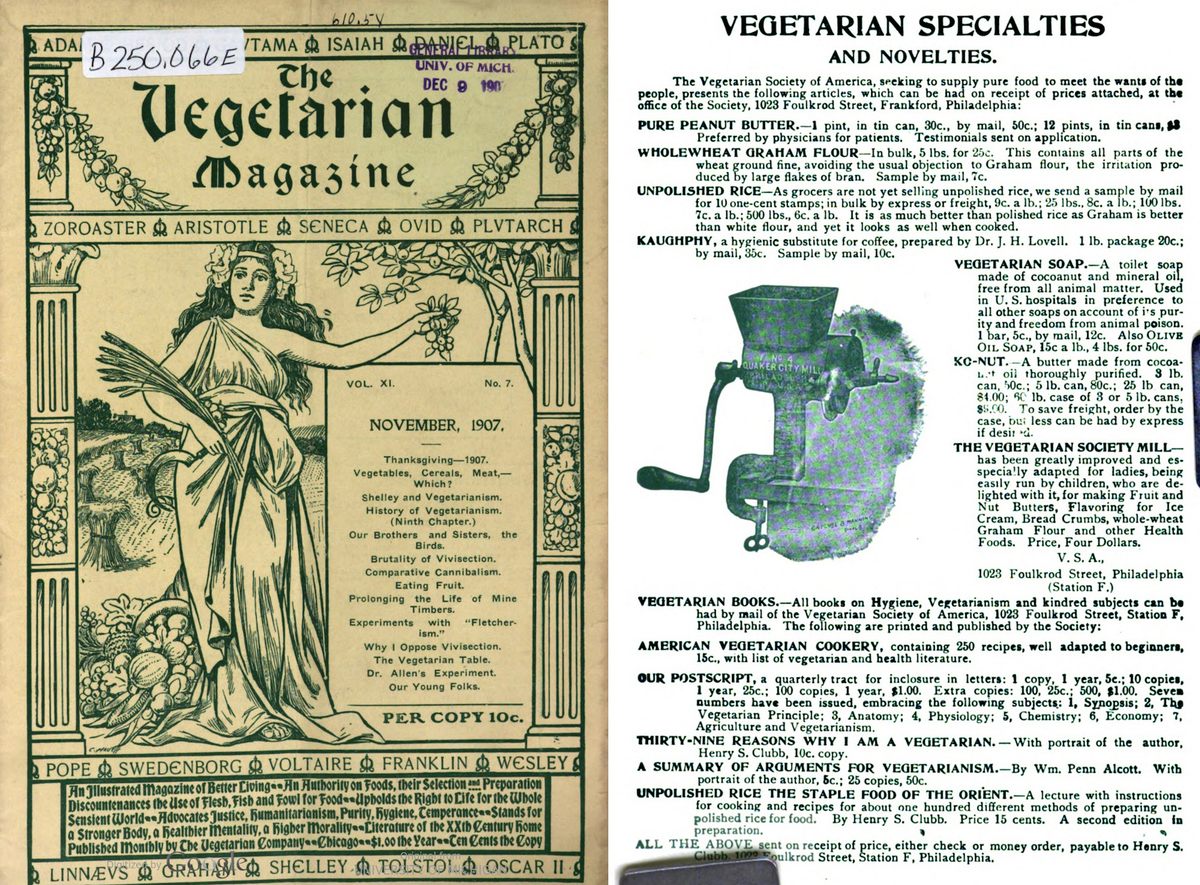

Earlier in the 1800s, as historian Adam Shprintzen chronicles in The Vegetarian Crusade, America’s meatless movement had sought to link a flesh-free diet with abolition, suffrage, and pacifism into a campaign for broad social reform. But vegetarianism posed a threat to what was fast becoming an engrained American value: the production and consumption of red meat. Siding with flesh-eaters, the popular press mocked vegetarians as sickly, cowardly, girly, degenerate, dull-minded fad-chasers. And the scientific-medical establishment was no better, calling vegetarianism unnatural, unsafe, and the likely cause of unfortunate conditions ranging from gout and tuberculosis to the uncontrollable spewing of sperm and breast milk.

If the meatless movement were to survive, it needed a makeover. At the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, the First Vegetarian Congress and speakers such as Kellogg presented meat-abstinence not as a socio-political movement, but an individual diet that would bring physical betterment and prosperity. As Shprintzen observes, the Congress “mixed the language of American triumphalism with that of economic development to place the movement among the great social changes in the modern world.” That messaging struck a chord with Chicago’s upper-crust donor class (the Battle Creek demographic), who went on to nurture a growing industry of meatless businesses: groceries, clubs, magazines, cookbooks, and restaurants, including two eateries less than two blocks from Stagg’s Marshall Field.

In issue after issue, The Vegetarian magazine (published in Chicago) and Physical Culture (inspired by the 1893 World’s Fair Congress) explicitly linked vegetarianism with superior physical prowess. Breathlessly reporting Irving Fisher’s strength tests and gushing over athletes who credited their success to meat-free diets, the magazines worked overtime to combat the stereotype of vegetarian weakness. Physical Culture even published beefcake shots to celebrate the meatless male physique. More than mere strength, they wanted to assert vegetarian masculinity.

It was inevitable, then, that they would root for Stagg and his Maroons. What was more masculine than football?

As Chicago racked up its early wins, vegetarian and meat-eating onlookers publicly grappled with the implications. One commentator wryly linked the Maroons’ vegetarianism with their unique mastery of what everyone was calling “the new football”: “It is less a game of beef than ever, and speed and tricks are the main ingredients for success.”

But not everyone was so eager to banish football’s brawnier side to history. In a gossipy, unnamed, late October editorial, one newsman claimed, without substantiation, that the Maroons were not going flesh-free at all and the whole “Vegetarians” story must have been some kind of scam. The game at Minnesota would be a “contest of beefeaters,” he ranted, “with plenty of red corpuscles in their blood supply.” Was he, as a Maroons fan, trying to scare Minnesota? Or was he, as a meat fan, scared of the Maroons’ success?

On the contest’s eve, Minnesota’s preparation for their own “purity banquet” made for comic relief in the Inter-Urban, which speculated that in lieu of “that horrible packing house beef,” stewed prunes might be served to the visiting Maroons instead. In the end, the chef went out of his way to go nearly all-vegetarian, succumbing only minimally to the hosting team’s hankering for flesh.

The next day, the Gophers started strong, battering the Maroons’ defense and scoring first via drop kick. But midway through the first half, Chicago made its strength known, turning the game around with an unrelenting series of long, graceful forward passes. Each time the Maroons used this new “trick,” Minnesota was left flat-footed. Following a terrifying collapse of some bleachers early in the second half, the rest of the game belonged to Chicago, who triumphed 18-12.

All agreed: It was a victory of the whole team, led by the wily genius Stagg, who had mastered the new game like none other. No longer an Eckersall machine, Chicago was now a Maroons machine. Even “Eckie” dropped his “Vegetarians” schtick to give his former team and coach heartfelt praise.

In next week’s Purdue game, the only surprise was the sheer size of the blowout: The Maroons won 56-0. And no matter that the Maroons later lost to the Carlisle Indians, an out-of-conference game that Stagg groused had been terribly refereed. The Vegetarians were 1907’s Western Conference champions.

Stagg didn’t stay meatless for much longer. In his memoir, he recalls going flesh-free entirely for only two years, as part of a (failed) effort to eliminate the source of his chronic sciatic pain. Though for the remainder of his 102 years, he continued to forego alcohol, coffee, cigarettes, and swearing.

But what of the Maroons? The vegetarian experiment was not repeated by any of Stagg’s other teams that school year, and when fall football rolled around the next year, the coach made the news with another training gimmick: stimulation by oxygen. Though he continued to encourage a vegetarian-ish diet over red meat, by his own account, he gave up his strict devotion to a training table in just a few years, concluding that it was “not all essential in the training of the athletes.” Today, Stagg is remembered as a pioneer of college football (Marshall Field is now Stagg Field, the NCAA’s Division III Championship game is called the Stagg Bowl, and developments ranging from the tackling dummy to laterals are credited to him), but the 1907 meat-free championship is only a footnote to his storied career.

While no other football teams appear to have followed the Maroons’ lead, the vegetarian publicity machine continued to highlight the latest feats of meatless might, battling persistent mockery and criticism. By the mid-1910s, vegetarianism had gained a substantial new level of mainstream American acceptance. According to polls, 2.8 million Americans identified as vegetarian in 1943, and by 2008, that number had risen to 7.3 million, with almost 23 million eating mostly meat-free.

Among those millions are a growing number of professional athletes, including tennis legend Venus Williams, a host of NBA players, and “the 300-pound vegan,” David Carter, a former Chicago Bear. They point to a wealth of both anecdotal and scientific evidence that vegetarianism and veganism can not only reduce pain, blood pressure, and inflammation, but also boost energy, dexterity, and performance—largely the same claims evinced by Stagg, Kellogg, and vegetarian activists back in 1907.

In 2016, in the clearest echo of the Maroons’ experiment yet, eleven members of the Tennessee Titans football team adopted a meat-free, plant-based diet. At first, linebacker Wesley Woodyard was skeptical: “Y’all crazy with this vegan thing,” he recalls thinking. “I’m from LaGrange, Georgia. I’m going to eat my pork.” But soon enough, Woodyard, too, had converted. A hundred years after Stagg and his Vegetarians, meat-free muscularity has its spotlight again.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook