Did the Utopian Pirate Nation of Libertatia Ever Really Exist?

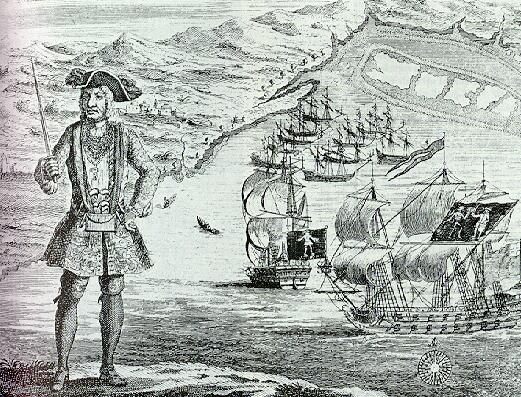

An engraving from Captain Charles Johnson’s A General History of Pirates. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

For twenty-odd years during the 17th century, on the coast of Madagascar, there was a democratic colony comprised of surprisingly noble pirates who lived together in peace and harmony. They bankrolled their colony with spoils stolen from evil slave ships traversing the Indian Ocean. This astonishing place, next to the sea “abounding with fish,” was called Libertatia. Like Camelot, it flourished briefly, before forces beyond its control swept it all away.

If it sounds too good to be true, the stuff that blockbuster movies and comic books are made of, it may be because it is. Our main source of information about Libertatia (also referred to as Libertalia) comes from two chapters in the 2nd edition of Captain Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pirates, published in 1726.

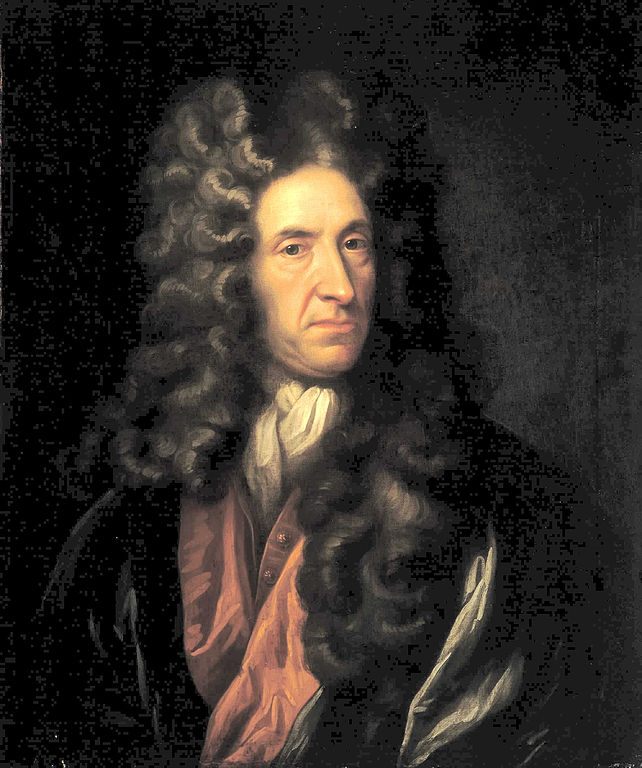

Many scholars now believe that Johnson was in fact a pseudonym for the writer and political activist Daniel Defoe. However, many of the tales told in A General History have been proven to be based in historical truth, so there is a chance that Libertatia, or places like it, did exist.

The coast of Madagascar, the location of “Libertatia”. (Photo: FrontierOfficial/flickr)

Johnson’s account begins with an introduction to Libertatia’s founder, the highborn and handsome Captain James Misson:

We can be somewhat particular in the life of this gentleman Misson, because by a very great accident, we have got into our hands a French manuscript in which he himself gives a detail of his actions. He was born in Provence, of an ancient family; his father, whose true name he conceals, was master of a plentiful fortune, but having a great number of children, our rover had but little hopes of other fortune than what he could carve out for himself with his sword.

In search of his place in the world, Misson joined the crew of the French privateering ship Victoire. On his travels, he met a free thinking Dominican priest named Caraccioli. This “lewd” priest would become Misson’s right hand man, and the brains behind Libertatia. Caraccioli was a deist, who believed organized religion was used to control the masses. Soon, Misson adopted his views and “began to figure to himself that all religion was no more than a curb up the minds of the weaker, which the wiser sort yielded to in appearance only.” Caraccioli also believed slavery was inherently wrong and that all men were born free and equal in the eyes of God.

“Captain Charles Johnson” is believed to be a pseudonym for writer Daniel Defoe, pictured. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Soon, many of the ship’s crew had been converted to Caraccioli’s revolutionary ideas. When the ship’s captain was killed during a battle at sea, Misson was proclaimed the Victoire’s new leader. In a rousing speech, Caraccioli and Misson convinced the French, Dutch, English and African sailors to throw off their “official” French chains, and become pirates of no nation, devoted to a higher cause:

As we then do not proceed upon the same ground with pirates, who are men of dissolute lives and no principles, let us scorn to take their colors. Ours is a brave, a just, an innocent, and a noble cause; the cause of liberty…The cabin door was left open, and the bulk-head which was of canvas rolled up, the steerage being full of men, who lent an attentive ear, they cried, “Liberty! Liberty! We are free men! Vive, the brave Captain Misson and the noble Lieutenant Caraccioli.”

And so this new band of idealistic pirates took off for the southern coast of Africa. They traveled around the Cape of Good Hope, engaging merchant and slave ships in battles along the way. They rescued many slaves and mistreated sailors, declaring them free men and integrating them into their crew. They were also remarkably lenient and respectful in the way they handled the captains on these ships, since neither Misson nor Caraccioli believed in capital punishment or torture, except in extreme cases.

A beach on the east coast of Grande Comore, part of the Comoros Islands. (Photo: David Stanley/flickr)

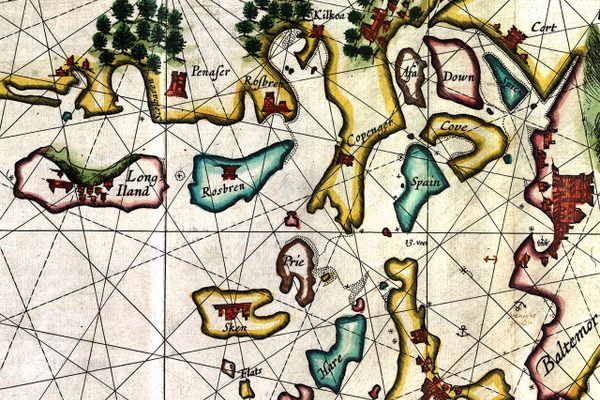

Laden with booty from these encounters (which was shared equally), they made their way to the island of Johanna, now called Anjouan, in the Comoros Islands. Here, they offered their services to Queen Halina, and fought for her against her brother, who had challenged her throne. Some of the men took wives and stayed in Johanna, while the rest followed Captain Misson and Caraccioli (both of whom had also married native women) to the north coast of Madagascar, in search of a permanent home-base. They found it at a “bay to the northward of Diego- Suarez (now Antsiranana).” According to Johnson:

He [Misson] ran ten leagues up this Bay, and on the larboard side found it afforded a large and safe harbor with plenty of fresh water. He came here to an anchor, went ashore and examined the nature of the soil, which he found rich, the air wholesome and the country level. He told his men that this was an excellent place for an asylum, and that he determined to fortify and raise a small town, and make docks for shipping, that they might have some place to call their own, and a receptacle when age or wounds had rendered them incapable of hardship, where they might enjoy the fruits of their labor, and go to their graves in peace: that he would not, however, set about this, till he had the approbation of the whole company.”

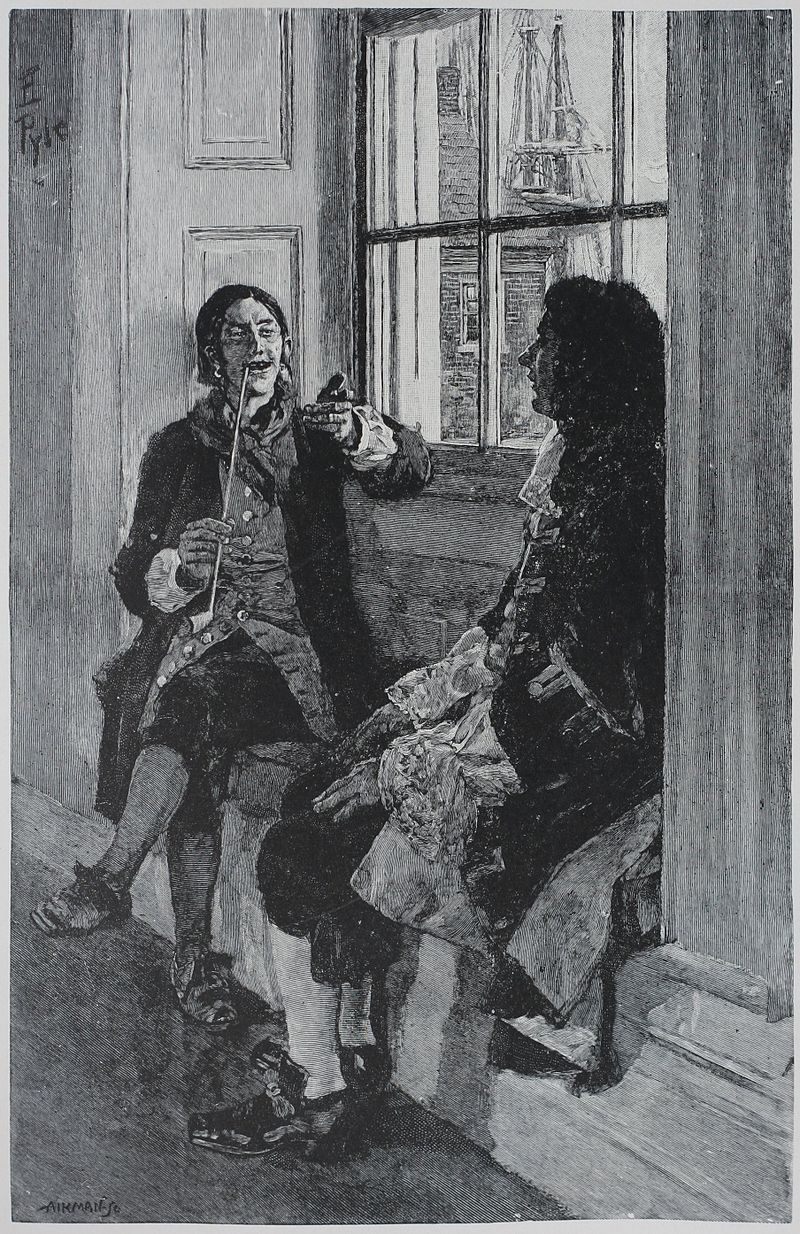

The men named this new settlement Libertatia. They shed their old nationalities and called themselves “liberi.” They began to fashion their own language, a mixture of their various native tongues and local dialects. Around this time, they met up with the very real Englishman, Captain Thomas Tew, a privateer turned pirate, who joined Libertatia along with his men. The “liberi” began to construct a town out of the wilds of Madagascar. The men who had stayed in Johanna arrived with their wives and young children. As the colony grew, some men went out with Captain Tew and other leaders to continue hunting down merchant and slave ships in the Indian Ocean.

An illustration of the privateer turned pirate Captain Thomas Tew, relating his exploits to Governor Fletcher of New York. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Within a few years, Libertatia was flourishing. They had “cleared, sown and enclosed a good parcel of ground, and taken in a quantity of pasturage, where they had above 300 head of black cattle, bought from the locals. The dock was now finished, and the Victoire, growing old and unfit for a long voyage…she was pulled to pieces and rebuilt, keeping the same name.” Life was lived in a communal way, with every man sharing in both the work load and the spoils of the sea.

However, tensions grew between Tew and Misson’s men, leading to a proposal of a new form of governance for the pirate nation:

The whole colony was assembled and the three commanders [Misson, Caraccioli and Tew] proposed a form of government being taken up…that looked upon a democratical form, where the people were themselves the makers and judges of their own laws… they would divide themselves into companies of ten men, and every such company choose one to assist in the settling of a form of government and in making wholesome laws for the good of the whole.”

The men agreed to this system of government. Caraccioli also “spoke to the necessity of lodging a supreme power in the hands of one who should have that of rewarding brave and virtuous actions and of punishing the vicious, according to the laws which the state should make.” This would not be a hereditary position, but an elected one, determined by a public election every three years. Not surprisingly, he put Misson forward for the nomination, and he was duly elected.

However, this new style of government would not last for long. While Captain Tew was at sea, native peoples attacked Libertatia. Caraccioli was killed along with many other “liberis.” Captain Misson escaped with 40 odd men and a treasure trove of booty. He met up with Captain Tew, who tried to convince him to go to America and establish a colony there. The heartbroken Misson declined, “for his misfortunes had erased all thoughts of future settlements; that what riches they had saved he would distribute equally, nay, he would be content, if he had only a bare support left him.“

Soon after, Misson and the Victoire went down during a violent storm. The Libertatia experiment had officially come to an end.

The pirate cemetery at Île Ste-Marie, Madagascar. (Photo: JialiangGao/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 4.0)

So, is this amazing story true? Even if Libertatia was a figment of Defoe’s (or some other ghost writer’s) imagination, it is certainly rooted in some historical fact. There is no doubt that many pirates spent time in Madagascar and the Comoros Islands, and there is strong evidence to suggest that they made places like Johanna and Madagascar’s Ile Sainte- Marie their home base.

Madagascar had long been considered a kind of freeman’s paradise. As early as 1640, a man named Walter Hammond wrote a book entitled A Paradox Proving That the Inhabitants of the Isle Called Madagascar… Are the Happiest People in the World. There are also tales of documented pirates like Henry Every establishing idealistic colonies on sparsely populated islands.

The scholar Marcus Rediker believes that the values espoused in the tale of Captain Misson were similar to those held by many pirate crews. During the 16th and 17th centuries, the common sailor’s life was very difficult. According to Rediker, one observer said, “being in a ship is being in jail with the chance of being drowned…a man in jail has more room, better food and commonly better company.”

Many sailors became pirates to escape these horrible conditions. Contrary to the stereotype of the tyrannical Captain Hook, heads of pirate ships often had very little real power. As one onlooker stated, “they permit him to be captain, on condition, that they may be captain over him.”

An engraving of a pirate custom: walking the plank. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Pirates were often multi-cultural crews, and many crews had members who had formerly been African slaves. They often drew up constitutions and cast off their original identities, claiming to be “from the seas.” According to Rediker, “the very first item in [pirate] Bartholomew Robert’s articles guaranteed every man a vote in affairs of movement and equal title to fresh provisions and strong liquors.”

This piratical way of life would no doubt have been appealing to Daniel Defoe. The author was a staunch reformist, who spent time in debtor’s prison. He had very progressive views regarding religion, commerce and liberty. As a British citizen with ties to the crown, it would have been dangerous for him to voice his support of a democratic nation. Perhaps, Captain Misson was created to speak for Defoe.

This possibility has not stopped many explorers from searching for proof of Libertatia’s existence. Journalist Kevin Rushby’s quest to find these pirate utopias took him on a journey though Mozambique, the Quirimbas Islands, the Comoros Islands and Madagascar. Along the way, he met many people who claimed to be descendants of pirates, a pirate grave, an old cauldron, a house reported to be the home where Misson met with Queen Halina–but little else.

If Libertatia ever existed, it seems the jungle and the sea have swallowed up the proof. But really, isn’t Libertatia just an ideal we are all still in search of? Who doesn’t want to believe in a seaside paradise where weary wanderers might, as Captain Charles Johnson wrote, “enjoy the fruits of their labor, and go to their graves in peace”?

![Anne Bonny and Mary Read were both "convicted of piracy at a Court of Vice Admiralty [and] held at St. Jago de la Vega on the Island of Jamaica, 28th November 1720," according to the inscription accompanying this 1724 Benjamin Cole engraving from <em>A General History of the Pyrates</em>, by Daniel Defoe and Charles Johnson.](https://img.atlasobscura.com/5_kDHgENxQkc0QzZuPs_kICvmEP5JNCV8bcXDI7m5Do/rs:fill:600:400:1/g:ce/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy81NDQ0ZGNiMi1m/YzRkLTQ4YjUtYTVh/MC0xYzU2ZDliOTY0/YjY1NGNkMWI4MWEw/OTExMDM5ZTZfQW5u/ZSBCb25ueSBhbmQg/TWFyeSBSZWFkIC0g/RmVtYWxlIFBpcmF0/ZXMgaW4gMTgwMHMu/anBn.jpg)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook