Finding the Real Transnistria: Where the Soviet Union Forgot to Die

Transnistria. If the name draws a blank, then don’t worry – you’re not alone. This tiny sliver of land located along the Dniester River between Moldova and Ukraine is almost unanimously unrecognized. Even amongst the relatively few Westerners aware of its existence, Transnistria is best known as the time-locked non-nation where the Soviet Union forgot to die. Such preconceptions do a disservice, however, to what is in reality a fascinating, safe, and largely misunderstood region of Eastern Europe.

Transnistria’s independence, contested as it may be, came by way of the War of Transnistria (1990-92). Under the Soviet regime, this region was a special industrial zone, and when the former Soviet Socialist Republic of Moldova morphed into today’s democratic Republic of Moldova, the Transnistrian province was loathe to relinquish its ties with Moscow.

The region was supposedly responsible for large-scale weapons manufacturing for the USSR, and Russia’s continued military investment in Transnistria would appear to lend credence to such stories. It was Russian soldiers who ultimately drove the War of Transnistria into the uneasy ceasefire which has held since July of 1992. The Moldova-Transnistria border is patrolled by Russian tanks to this day, and, in the wake of the recent troubles in Ukraine, the Russian Federation upped its Transnistrian contingent, which now numbers at over 2,000 stationed troops.

Military parade on Transnistria’s Independence Day (photograph by Darmon Richter)

A map of the Transnistrian region (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Soldiers parade outside popular local fast food joints (photograph by Darmon Richter)

But that’s politics. Transnistria features in the Western media rarely enough, and when a journalist does visit they’re usually chasing up a story about the oft-reported bribery and corruption, or simply gawping at the proliferation of Soviet symbolism in this small, unrecognized state.

Such themes, however, are neither unique to Transnistria nor are they representative of the local culture and lifestyle. In the case of Soviet symbolism, one need only look to other post-USSR nations such as Russia, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine, to find similarly ominous icons of the past.

The fuss made about corrupt government, about police bribes, and dubious accounting, generally seems to be leveled by those with no real experience of travel. One can’t help but wonder if these journalists have ever ventured further east than Germany; from the Balkans to the Baltic States, bribery and corruption are rife. In this respect, Transnistria is nothing new.

Having said that, in some ways it is. The government of Transnistria recently made an increased bid to welcome foreign tourism, backed by the introduction of an official “Anti-Corruption Minister.” The potential punishments are steep for those who prey on visitors; tourists who demonstrate this knowledge, even just by flashing a number on the screen of their mobile phone, are usually able to get the better of border guards, police, or any other officials who persist in trying their luck for an illicit bribe. In this respect, travellers in Transnistria enjoy more security than those visiting many other Eastern European nations.

A bust of Lenin in a rural corner of Transnistria (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Inside an abandoned factory just outside Tiraspol (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Bleak architecture dating from the years of the USSR (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Some journalists have branded Transnistria as unfriendly, or unwelcoming; more often than not, this boils down to a linguistic matter. Russian is the de facto language of Transnistria, and while many of the nation’s younger generation have no problem communicating in English, the same can’t be assumed for everyone you’ll meet. If you expect waiters, bus drivers, and shop keepers to cater to your needs in English, then you’re absolutely likely to perceive a certain degree of unfriendliness at times. Much like one would in France. Or in Japan. Or in fact, as anyone might experience if they attempted to tour Britain or much of the United States without a basic grasp of the English language.

In Transnistria, learning the local language is considered by many to be a basic, common courtesy. You don’t have to be fluent, but as is the case when visiting Mother Russia herself, a few basic phrases and a little effort on your part will go a long way towards turning that frosty reception reported by some lazy travelers, into a warm and genuine welcome.

Another criticism often leveled at Transnistria is that there’s simply nothing to do, from international news media down to humble travel bloggers, there seems to be a resounding opinion that beyond the novelty of hammers, sickles, and great big busts of Lenin, Tiraspol – the Transnistrian capital – is a bit boring.

The central boulevard in Tiraspol, capital of Transnistria (photograph by Darmon Richter)

A marble Lenin beneath the flag of Transnistria (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Pobeda Park, in the heart of Tiraspol (photograph by Darmon Richter)

True, the city is a fairly standard Soviet affair: wide streets, whitewashed pavements, colorful propaganda posters. It could be anywhere from Pyongyang to Havana, with its clean and efficient appearance, its brutalist architecture, and militaristic culture. Aside from the annual Independence Day parade on September 2nd, it’s a fairly quiet place, and if you just came on a day trip to the capital then you might be forgiven for thinking there wasn’t much going on. It’s not until you make the effort to get outside of Tiraspol that you discover the true magic of Transnistria.

Transport is easy — hop on one of the taxi-buses (or marshrutkas) that stop along the capital’s main streets, and you can get to more or less anywhere in Transnistria for a handful of rubles. You won’t find the best attractions in guidebooks — Rough Guides, Lonely Planet, they barely touch the place — but travel here is rather a case of true exploration. Follow your nose. Talk to the locals.

At Bendery, a town on the Moldovan border, visitors can tour a 16th century Ottoman fortress, or dive into local history at the Bendery Military Museum, itself tucked away in the carriages of a decommissioned Soviet steam train.

The Bendery Military Museum (photograph by Darmon Richter)

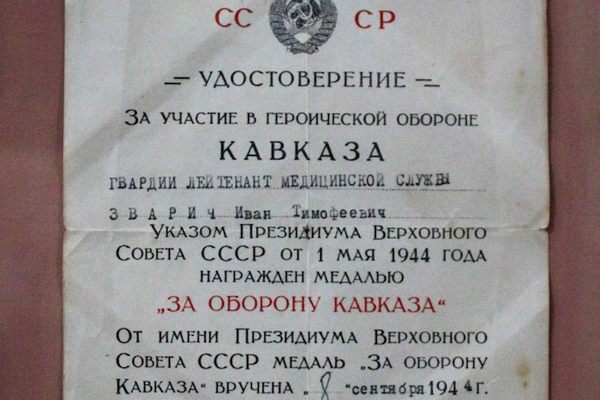

A museum exhibit inside one of the train carriages (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Documents dating back to Transnistria’s Soviet years (photograph by Darmon Richter)

The obelisk outside of Chitscani (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Then there’s Chitscani, a little way south of the capital. This important former battleground is presided over by a bold and dramatic obelisk, a stark Russian symbol that belies the complicated blend of identities in this rural town.

“Welcome to Moldova,” is the greeting you’ll get from priests at the Noul Neamt Monastery on the edge of town. The site was drastically downsized when the communists arrived, a priest explained, with numerous buildings annexed or destroyed. But unlike other Eastern European nations, where such conversations carry the implicit conclusion of, “and then the communists left,” here in Chitscani the orthodox faith remains in a state of siege.

In fact, the monks are so excited to receive guests from the West — tourists looking for genuine history and culture rather than simply to marvel at retrogressive political ephemera — that they’ll often offer a full, personalized tour, from the top of the Noul Neamt bell tower, down to the crypt which houses the bones of the monastery’s founding fathers.

The Noul Neamt Monastery, seen from the top of its bell tower (photograph by Darmon Richter)

The monastery’s interior is decorated with richly detailed orthodox murals (photograph by Darmon Richter)

An altarpiece in the Noul Neamt Monastery (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Transnistria is safe. It is friendly, welcoming, and filled to bursting with living human history. Further to that (and without wanting to get too drawn into the debate over official recognition), the culture here is notably different from Transnistria’s parent republic of Moldova.

The state’s close ties with Moscow have resulted in something that isn’t quite Moldovan — the language is different, the architecture, the customs, the politics, the identity overall far removed — but at the same time Transnistria offers too much parochial charm to be fairly considered the “Russian holiday resort” that so many fleeting visitors to the capital perceive.

A banner advertising the September 2nd Independence Day celebrations (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Independence Day means military parades, followed by barbecues in the park (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Transnistrian fast food — barbecued meat with lashings of vodka (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Transnistria is also notably wealthier than either its neighboring Moldova, or Ukraine. The roads are better and cleaner, and the streets are lined with stores that sell tablets and professional cameras. Plenty of journalists speculate about where exactly that money comes from: arms manufacturing being a popular theory in the West, where many spectators view this unrecognized nation as a soulless Russian puppet, or a front for money laundering on a national scale.

The Transnistrian people themselves are real, though. Ask them about politics and they’ll often shrug, dismissing such talk in favor of the very obvious comforts, culture, and rich history that surrounds them. They have everything they need. Most prefer to enjoy their lives, and not to question politics.

If a Western outsider can manage to do the same then — to visit Transnistria with an open mind, and without the baggage of one’s own political or journalistic agenda — the result is one of stumbling across an uncharted and wholly captivating land, a uniquely unexplored time capsule tucked away in the rolling hills of Eastern Europe.

Children play on a decommissioned tank in the heart of Tiraspol (photograph by Darmon Richter)

The Noul Neamt Monastery at Chitscani (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Taking a walk through the Transnistrian countryside (photograph by Darmon Richter)

A statue of Lenin in the capital (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Outdoor art class in a city-center park (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Sunset over Tiraspol (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Darmon Richter is a freelance writer, photographer, and urban explorer. You can follow his adventures at The Bohemian Blog, or for regular updates, follow The Bohemian Blog on Facebook.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook