The German-Language Newspaper That Got the Scoop on American Independence

On July 5, 1776, only the “Pennsylvanischer Staatsbote” reported the big news.

On Thursday, July 4, 1776, Heinrich Miller, a 50-year veteran of the newspaper business and publisher of Heinrich Miller’s Pennsylvanischer Staatsbote (Heinrich Miller’s Pennsylvania State-Courier), played a familiar game of hurry up and wait.

During the American Revolution, news traveled slowly but broke abruptly—nowhere more so than in Philadelphia, where the Second Continental Congress deliberated daily over matters with profound historical consequences. As Miller spent the day laboriously setting type and doling out instructions to his apprentices for the Friday edition, he knew that landmark news might reach his printing house moments too late to publish.

On Tuesday and Wednesday that same week, Miller, an ardent revolutionary, had watched his competitors at the Pennsylvania Evening Post and the Pennsylvania Gazette hurriedly print reports that Congress had voted to declare “THE UNITED COLONIES FREE and INDEPENDENT STATES.” Though Miller published the Staatsbote on Tuesdays as well, he seems to have received the news too late to include it in that day’s issue. On Thursday, however, he caught a break.

On the day Americans now celebrate as Independence Day, Miller learned that Congress had drafted and signed an official declaration renouncing British rule and naming the 13 independent sovereign states a new country. As luck would have it, he was the only printer in town to issue his paper on Fridays.

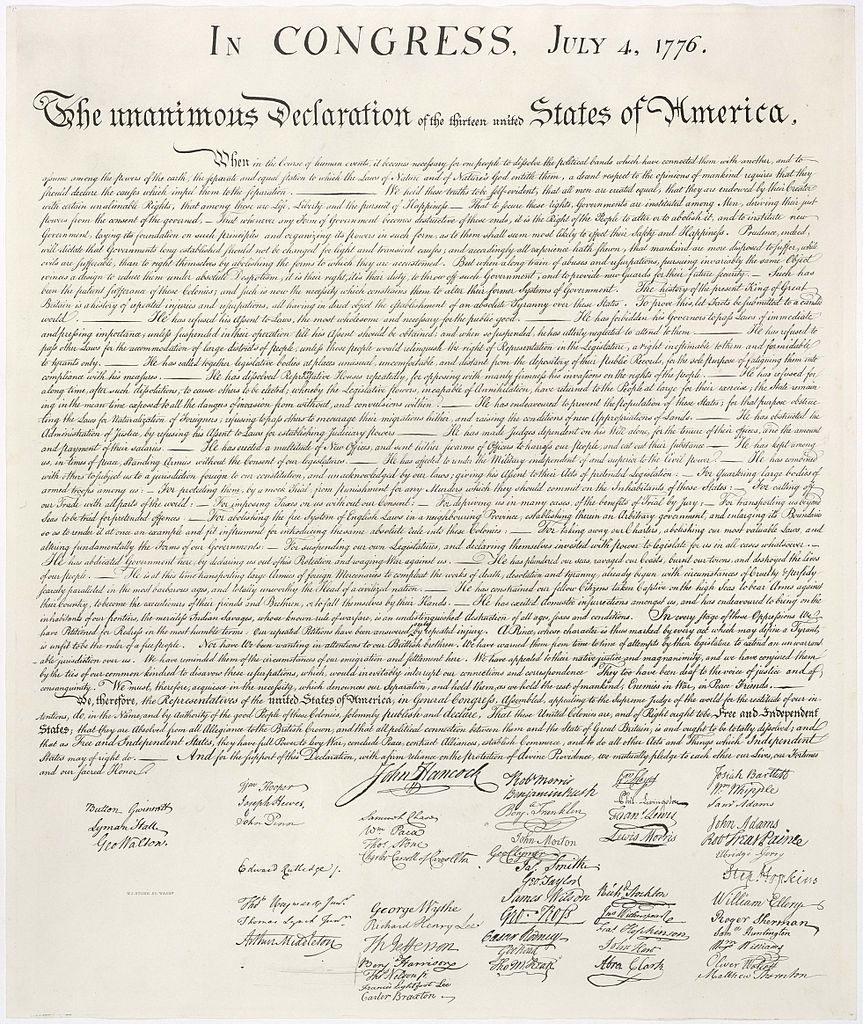

The next morning, Miller secured his place in history. Finding just enough room at the bottom of the first column on his second page, he became the first publisher to report the existence of the Declaration of Independence.

“Gestern hat der Achtbare Congreß dieses Westen Landes die Vereinigten Colonien Freye und unabhängig Staaten erkläret,” he wrote in 18th-century German. “Die Declaration in Englisch ist jetzt in der Presse; sie ist datirt, den 4ten July, 1776, und wird heut oder morgen im druck erscheinen.”

Translation: “Yesterday, the honorable Congress of these Western Lands, declared the United Colonies free and independent states.The Declaration is in English and is now at the Press; it is dated July 4th, 1776, and will be published either today or tomorrow.”

According to historian Joseph Adelman, author of Revolutionary Networks: The Business and Politics of Printing the News 1763–1789, Miller was more fortunate than skillful in scooping his competition on the signing. “Most 18th-century newspapers were weekly,” he says. “Publication dates were pretty well set and usually timed with post riders.” Papers reported important events exclusively when they occurred on or around the days they published.

But that didn’t mean that publishers ignored breaking news. Philadelphia boasted one of the most competitive media markets in British North America. With at least six major newspapers at the time, Adelman says, “there was plenty of incentive to publish what they would have called ‘the freshest advices.’”

Miller had a long history of securing such “advices.” Born Johann Heinrich Müller in the village of Rhoden (located in what is now Saxony-Anhalt), he entered the printing business in 1715, at the age of 13. Over the next 15 years, he worked in printing houses in Basel, Switzerland; Altona, Germany; London; and Amsterdam.

In 1741 he emigrated to Pennsylvania, where he found immediate work at Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette. Miller and Franklin got along well—so much so that Franklin hired him 10 years later to publish a German-language newspaper in Lancaster, where he hoped to build an audience among the scores of immigrants then flocking to Pennsylvania’s frontier.

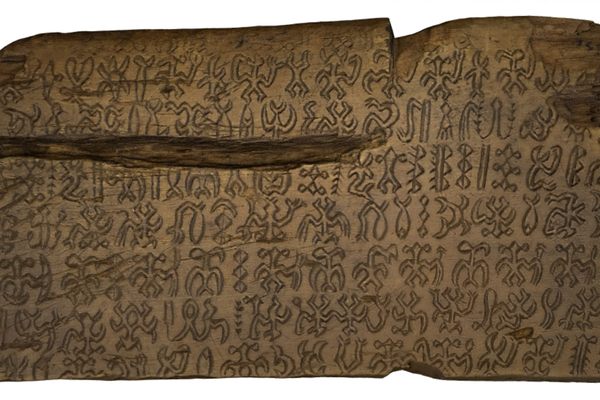

Between 1724 and 1755, tens of thousands of German-speaking settlers entered America through the port of Philadelphia. Most came from a region in southwest Germany known as the Palatinate. By 1754, Thomas Penn, the proprietor of Pennsylvania, believed that as many as 100,000 of these immigrants were living in his colony. Based on general population data published in the May 1755 edition of The London Magazine, this meant that Germans represented just under half of all Pennsylvania residents. In 1976, historian Lester Cappon estimated that by the time of the Revolution, Germans constituted one-tenth of British North America’s entire population.

Many of these settlers actively engaged with political and cultural affairs, creating demand for a vibrant German-language press in the colonies. Between 1740 and 1758, a publisher named Christopher Sauer dominated this market with his widely read Pensylvanische Berichte (Pennsylvania Reports). His death, in 1758, created a vacuum, which Miller filled in 1762 with his Pennsylvanischer Staatsbote.

The paper was a huge success. By the time it reached its peak in the 1770s, Miller had hired agents to disseminate the Staatsbote across the Atlantic World, from Nova Scotia to the West Indies.

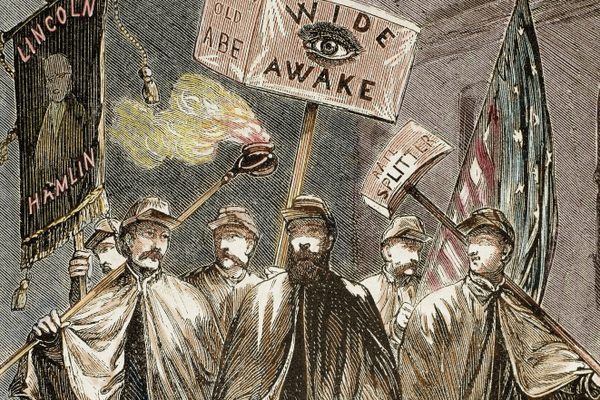

Miller particularly thrived during the Revolution. In May 1775, demand from his readers prompted him to publish his paper twice a week—a decision that better allowed him to keep up with key events. This included extensive reporting on the key battles of Lexington and Concord, Bunker Hill, and—perhaps most relevant to his German readership—King George III’s employment of Hessian mercenaries.

“The Hessians, Brunswickers, Waldeckers, and Hanoverians are said to amount to 20,000 men,” Miller reported on May 7, 1776. “O George!” he exclaimed. “Sind diese deine Friedens-boten!” [“Oh George! Are these your messengers of peace!]

Perhaps most impressive was Miller’s full German-language translation of the Declaration of Independence. Printed near the top of the July 9, 1776 issue of the Staatsbote, it masterfully channeled the document’s original language and tone, allowing German Pennsylvanians to share an authentic and historic experience with their English-speaking neighbors. Adelman says Miller’s ornately designed edition “mirrored the text setting of John Dunlap’s original broadside in both size and layout.” That suggests that Miller based his design on Dunlap’s first printing, which he likely received between July 4 and 5.

Unfortunately for Miller, the war itself eventually caught up to him. When the British occupied Philadelphia, in September 1777, they accused him of secretly working for Franklin, a prominent revolutionary. Miller was forced to flee the city and remain in hiding for several months.

He was, however, able to return to Philadelphia the following year, after the British left, and continued to publish the Staatsbote until he retired in 1779, at the age of 77.

“I did what I could,” he wrote in his farewell issue. “My loyalty to this country is, I hope, well enough known. And as far as my respect for the German nation is concerned, I wish every German to understand their worthiness.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook