The Strange Tale of the Great 1911 Trans-Saharan Ostrich Heist

Big hats, big risks, big payoffs.

It was 1911, and the Union of South Africa was awash with rumor and suspicion. It was said that there was a turncoat who had deserted the Ministry of Agriculture to sell secrets to a shadowy syndicate of American capitalists. South Africa had only been autonomous—as a dominion of the British Empire—for about a year. Any disruption to a major industry could be very damaging to the fledgling country.

In response, the parliament authorized a clandestine expedition to the Sahel, the semi-arid region south of the Sahara. The expedition was led by Russell Thornton, a veteran of the Boer War and two other “competent experts.” The alleged traitor? None other than Thornton’s brother, Earnest, a former employee of the Secretary of Agriculture.

Their mission was to secure a flock of ostriches—by any means necessary.

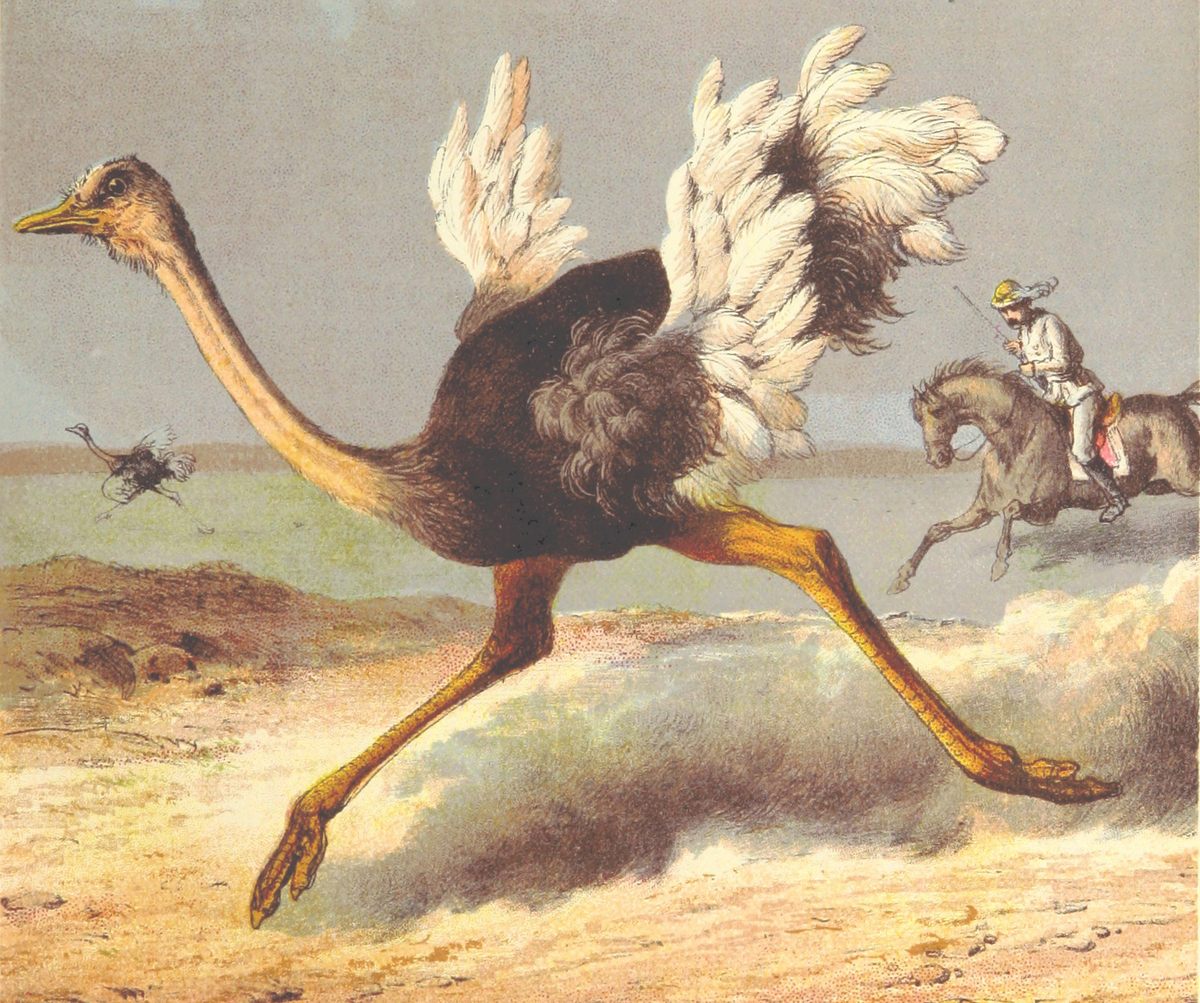

What’s the weirdest bird? The ostrich,” says Arne Mooers, professor of biodiversity at Simon Fraser University, “They may be the most [evolutionarily] isolated species in the world.”* Massive and flightless, ostriches thrive in arid environments, insulated from both heat and cold by their thick plumage. And they have the biggest bodies and largest eggs of any living avian. According to a 2014 study, ostriches and their closest relatives—the group including emus, cassowaries, and kiwis—diverged when there were still dinosaurs walking the earth. “They are different because they’re a long [evolutionary] branch, with a flowering at the end,“ explains Mooers—two species and a couple of subspecies, ranging across central and southern Africa.

There were ostriches around when humans emerged, so we have a long history with the massive birds. Africans had long hunted ostriches for meat and leather. In ancient Egypt, the goddess Maat and divine justice were represented by the ostrich feather, and two of them adorned the crowns of pharaohs as a symbol of authority. Ostrich eggs were carved and given as offerings in ancient Greece, and later they were used to adorn minarets. In the Ottoman Empire, the Arabian ostrich was hunted for sport, and those showy feathers.

But it wasn’t until the last decades of the 19th century that ostriches—their feathers, in particular—became a global commodity.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, exotic plumes, wings, and whole, taxidermied birds (and other animals) were used to trim ever more elaborate women’s hats. By 1911 hats had reached their apex size, and ostrich feathers, due to their volume and versatility, were particularly prized and commanded hefty prices.

At the time, South Africa provided 85 percent of planet’s ostrich feathers. The remainder mostly came from North Africa, through traditional trans-Saharan trade routes, usually by camel. This new status quo was all very good for South Africa. Ostrich feathers were its third most lucrative export, and the government had seized land from indigenous people and Dutch Boer settlers to create ostrich farms. Oudtshoorn became known as a feather town, where thousands of people, largely Jewish refugees from Lithuania, worked in the trade. Oudtshoorn was known as “Little Jerusalem.”

But there was one problem. South Africa didn’t actually have the best feathers on the market. The highest prices were paid for plumage from “Barbary ostriches,” a mysterious variety thought to come from North Africa. The Barbary ostrich (a term now sometimes used to refer to North African ostriches) was said to have thicker, more luxurious feathers than South African birds. But in truth, by the time these feathers reached market, they had passed through so many hands that their European buyers didn’t really know where they had come from. The South African government, to strengthen its grip on the market, wanted to know.

The South Africans got a clue as to the provenance of the Barbary plumage some time around 1910, when a lush, lustrous, full feather—just the kind that fetched the highest prices—reached the hands of the British consul in Tripoli, with a hint as to its origins. The British officials were able to say that it had come from “Southern Soudan,” meaning the colonial holdings in West Africa sometimes known as French Sudan (roughly present-day Mali and Niger). The British passed this information to their close friends in South Africa.

This was the intelligence—a possible location for the near-mythic Barbary ostrich—that South African officials feared Earnest Thornton would leak to the upstart American ostrich industry. If growers in California and Arizona got to the Barbary ostrich first, South Africa could be cut out of the New York hat industry entirely.

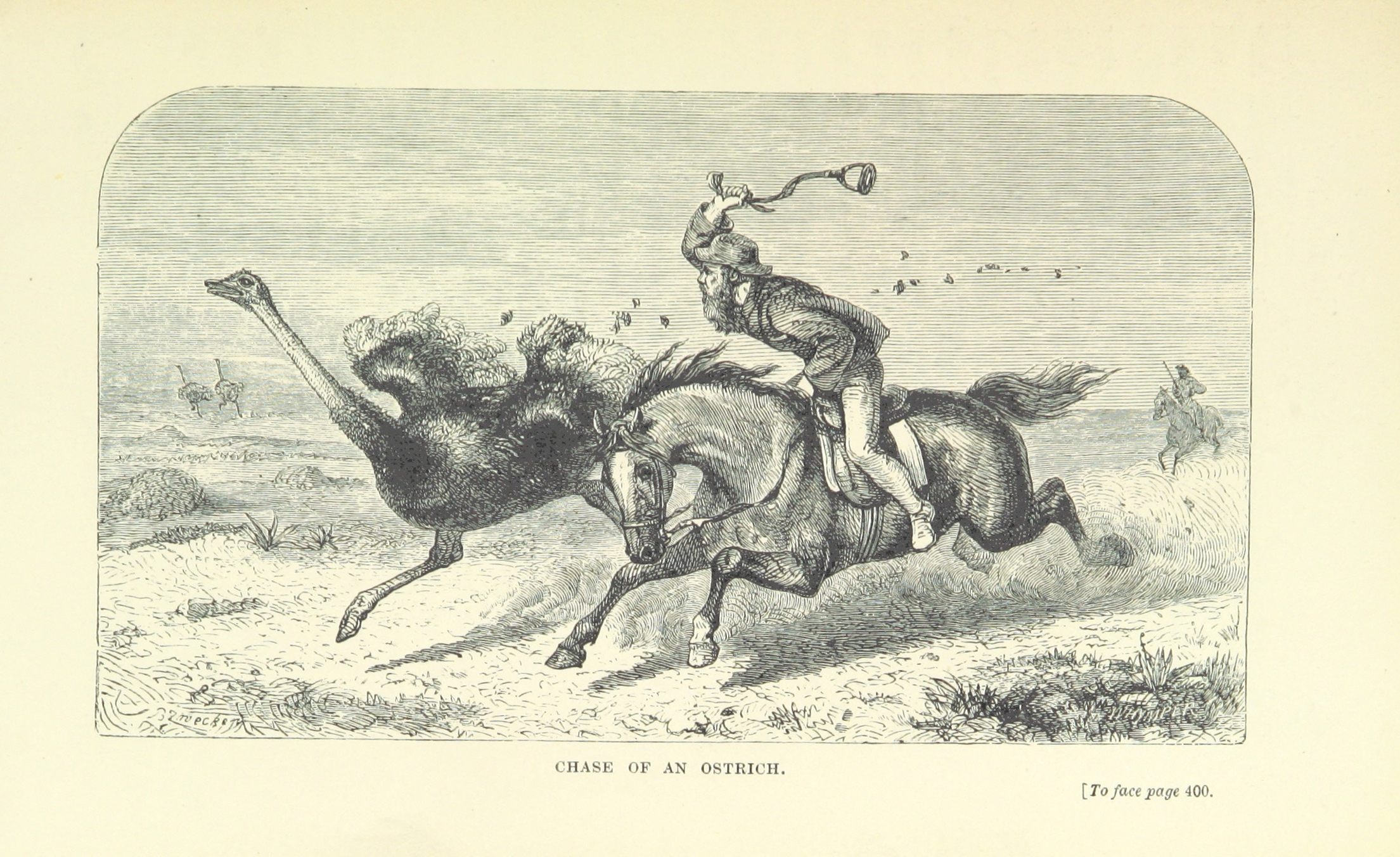

Russell Thornton’s mission, on behalf of the government, was to clandestinely make his way into French Sudan, locate the ostriches, and secure a flock for South Africa, before the Americans or local French officials, who had tried and failed to develop their own ostrich farms in Algeria, caught on.

But French Sudan was not a small region. Even with the lead, a daunting task faced Thornton and his conspirators, expert ostrich farmers Frank Smith and J.M.P. Bowker. They needed help. So they made their way to London to secure interpreters and desert gear.

Meanwhile, suspected ostrich spy Earnest, Russell’s brother, was waiting for the expedition in the United Kingdom, having returned from America. Before returning to South Africa, he explained to his brother that he was acting as a double-agent, independently spying on the American ostrich industry. He would later claim that his actions were intended to force the South African government to act on the Barbary ostrich lead. South African officials were not pleased with his behavior. “This was ostrich espionage, if you will,” says biologist Thor Hanson, author of the book Feathers: The Evolution of a Natural Miracle, which recounts the story. “It’s unclear who was spying on whom.”

Russell Thornton and his team then made their way to Paris for a secret meeting with a feather trader named “Hassin.” According to Sarah Stein, a scholar of Jewish history at the University of California, Los Angeles, “Hassin” was likely Isach Hassan, a prominent Jewish feather merchant whose family had traded in ostrich plumes for generations.

Merchant families such as Hassan’s had traditionally dominated the ostrich trade through relationships with North African officials. But by the 1880s, due to raids by nomads, the decline of the Ottoman Empire, and the European colonial “Scramble for Africa,” the trans-Saharan caravans carrying feathers and other goods to North African ports had suffered. Tripoli’s feather exports, for example, Stein cites, were down 90 percent compared with 20 years before.

Hassin (or Hassan) likely saw the writing on the wall. The shipments across the desert were dwindling. It was time to cash out. “Hassin’s counsel to Thornton’s crew,” whatever it was, writes Stein in Plumes: Ostrich Feathers, Jews and a Lost World of Global Commerce, “greased the wheels.” It’s likely that Hassin either pointed Thornton directly toward the ostriches or facilitated a meeting with the feather-dealing emir of Katsina, in northern Nigeria, or both.

Thornton and company set out for West Africa, and began their trek in the British colony of Nigeria. They chartered a steamboat from Forcados for a 500-mile voyage up the Niger River to Baro. From there they hopped a train to Kano, a major trans-Saharan trading city. In the bazaars there, Thornton inspected the ostrich feathers on offer. “Those from Zinder are the right type … according to all evidence the right type of feathers are from French territory,” he wrote in his journal.

Thornton wired back to South Africa, asking permission to cross into French territory. In the meantime he kept himself occupied with buying ostriches and plumes of the “right type”—the luxurious, expensive ones. Six weeks later he got the go-ahead from South African officials. The government authorized him to spend 7,000 pounds sterling to procure 150 ostriches—but also told him that they would disavow any association with him or his expedition if they were caught.

The party traveled 150 miles north through the desert to Fort Zinder in French Sudan (modern Niger). After a frustrating six weeks of negotiation, Thornton was rebuffed by the French colonial authorities. The export of live ostriches or their eggs was strictly prohibited. “The French were highly suspicious,“ says Hanson. “It doesn’t appear that the French understood the value of the ostriches, but they didn’t trust the South Africans’ motives.”

Thornton was forced to trek back to Kano with his tail between his legs. At this point the historical record becomes murky. We know that Thornton did eventually return to South Africa with a flock of ostriches. But no one really knows how he got it. French and American spies may have chased the expedition across the desert. The emir in Katsina, Hassin’s business partner, almost certainly helped procure some, if not the majority of them, from across the border. Thornton’s collaborators explored all the way to Lake Chad unsuccessfully seeking alternative sources, but the order of these events is unclear. In private correspondence, Thornton’s collaborator, Smith, hints at possible smuggling trips into French territory, with conflicts with nomads and French soldiers. Thornton’s family maintains that nothing of the sort ever happened, according to Hanson.

Whichever way it happened, Thornton’s team had secured a significant flock of ostriches, and marched them several hundred miles from Zaria, in northern Nigeria, to a train bound for Lagos. Thornton, wracked with malaria, was carried in a hammock. The ostriches were loaded into specially modified train cars, and then transferred to a ship bound for Cape Town; 140 survived the voyage. Thornton’s team was given a hero’s welcome. (Earnest, his reputation in tatters, retired from the trade.) The bold gambit had paid off. The future of South Africa’s ostrich feather monopoly was secure.

Two years later the feather market crashed. Hard.

The fate of the trade was sealed well before Thornton even departed for London. The Audubon Society and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds had been organizing against the mass killing of birds for millinery for years. In Massachusetts, Audubon founders Harriet Hemenway and Minna Hall “were not sympathetic with the idea that women needed plumes,” says Chris Leahy of Mass Audubon, and they forbade their members from wearing feathers or even imitation feathers. Bird-watching became a hobby of middle-class suffragettes. Thanks to their efforts, the U.S. government passed the Lacey Act to prevent the interstate trade in wild birds. Though ostriches and domestic birds were excluded from the legislation, the die had been cast. Feathers were on their way out.

Some larger trends truly sealed the market’s fate. The rise of the automobile made large, audacious hats far less practical. World War I austerity promoted simpler, less ornate fashions. The final nail in the coffin was the bob cut, a hairstyle entirely unsuited for supporting massive hats. Thousands worldwide lost their jobs as the feather-and-giant-hat industry collapsed.

The days of high feather prices gone, Thornton’s flock was never bred into South Africa’s domestic stock. The last bird from the flock, a male, was killed by a lightning strike sometime between 1939 and 1944. All the cloak-and-plume-and-dagger games came to nothing.

The ostriches from the region around Kano and Zinder, along the Niger-Nigeria border, met the same fate as the industry that coveted them. The French colonial administration may not have permitted official export of ostriches or feathers, but they weren’t paying enough attention to notice the unofficial trade, much less overhunting or habitat loss. “They didn’t send the brightest bulbs to Zinder,” says Hanson.

This entire incident is rather typical of the European approach to Africa as they split it up for exploitation, replacing long-standing practices, such as sustainable ostrich hunting for meat, with more destructive, extractive ones. According to University of California, Los Angeles historian Aomar Boum, the status of feathers as a commodity led to more ostrich hunting, but less ostrich eating. Instead, the animals were killed, plucked, and left for scavengers. Under those market pressures, it’s little surprise that the population of ostriches that Thornton attempted to raid is simply gone. It’s hard to say whether Thornton’s flock came from the currently endangered North African ostrich subspecies, or if they were something else entirely—now extinct.

*Correction: This piece originally misspelled Arne Mooers’s surname.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook