The Busy, Briny Lives of Iceland’s Herring Girls

From 1903 until 1969, women flocked to Siglufjörður to spend long hours gutting and packing fish.

Herring can be brined, smoked, or pickled in vinegar, brought to your table as matjes, kippers, or if you’re lucky, marinated in cream by Zabar’s deli on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Today the fish is automatically processed by fillet and brining machines. But up until a half a century ago, the process had historically been done by hand, specifically female hands.

They were called Herring Girls in the North Atlantic countries—places such as the Scottish Shetlands and Outer Hebrides, the Danish Faroe Islands, and Iceland. They were the women who processed the fishermen’s catch, standing for long hours on the piers, sorting, chopping, filleting the herring before brining and packing them in barrels. Like flocks of gulls, these women followed the fish supply to the cold-water ports where the Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) were so plentiful that a massive school could contain more than a billion fish.

In Iceland, from the 1910s through the 1960s, the herring industry was an economic life-raft for a far north Atlantic island nation burdened for centuries with food scarcity, inclement weather, and lack of a cooperative growing season. Before, during and after the world wars, Siglufjörður was the capital of the herring industry, accounting for 25-45 percent of total export earnings. During its heyday, this small town at the northern tip of a very northern fjord jutting out to the Greenland Sea was home to Iceland’s equivalent of the gold rush.

Herring is a highly perishable fish and the loads were large. The industry flourished because while the men fished the seas, coopered barrels, and worked in the fish meal factories, the women were needed to do the fast work of preserving the fish before it spoiled. From all over Iceland, women came to Siglufjörður from their small towns and family farms for the opportunity to make money.

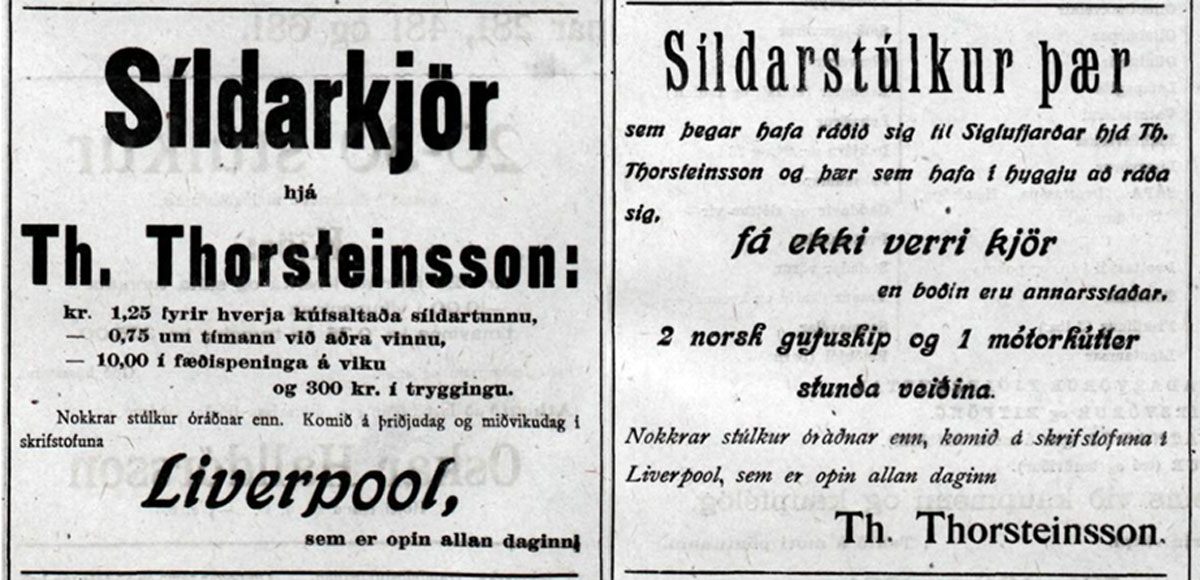

“During the 1930s, an active herring girl could earn as much as $10 a day,” says Anita Elefsen, Director of the Herring Era Museum in Siglufjörður. “Each girl gutted and packed their own barrel. After filling a barrel, a token was put in their boots, and the tokens were then exchanged for receipts at the end of the workday. Once a week they were paid out with cash.”

Margret Thoroddsdottir was born in Siglufjörður and worked for nine summers as a herring girl. She started when she was 14 in the summer of 1951. “As soon as the boats came in the girls were called to work. If it was at night, we were awakened by callers who had that specific duty. They would shout loudly, ‘Get up, get up – the herring has arrived!‘”

The work was hard, Elefsen says. “Since they were paid by the barrels, they competed with time to accomplish as much as possible every single work day, to earn as much as they could.”

“Depending on the catch, we would work all night if we had to,” says Thoroddsdottir. “Sometimes the work lasted for more than 24 hours straight.”

But then, these are the white nights of Icelandic summers—the town is a hair’s breadth from the Arctic Circle. There is no real darkness; night becomes a muted day, prolonged dusk until dawn finally shows. Icelanders are used to working under the night’s sun. It’s as if the solar energy seeps into their skin, creating seasonal indefatigability.

Like Alaska during the years of the Klondike Gold Rush, getting to Siglufjörður was difficult. Even today, there is only one road into town, Route 76, which takes you along a sweeping blind bluff of dizzying heights without any guardrails. Then the road pitches you into a one-lane tunnel with no red-green light warning you of oncoming traffic. But this is an improvement. From 1946 until 1967, when Route 76 was completed, there was only an old mountain pass. Before that, the only means of reaching Siglufjörður was by sea. Despite the remoteness, during the Herring Era, the town’s population quadrupled each summer.

Thoroddsdottir remembers it as a bustling, lively place. “There were two cinemas in town. And lots of romances going on as well. The town was full of young people working hard but also enjoying themselves as best they could. There were dance halls with live music on the weekends.”

The romances spurred an entire genre of popular music about the herring girls. And while Scotland and northern England have a few mournful ballads dedicated to the plight of their own herring ladies, Iceland’s musical tribute to their “fish women” is surprisingly energetic and upbeat, many employing an accordion with a waltz/polka beat. The contrast is striking. The songs are relentlessly buoyant and heady with temporal lust:

They greeted us with their merry song,

the herring girls,

and then the evenings were bright and long,

but the nights were sweetest.Because we were young and the love was pure

and our blood hot,

The summer passed and the sun shone

and the sea was boiling with herring.

The women were housed in Róaldsbrakki, which were rooms above the shipping offices. “The ones that came from around the country were provided with housing at the cost of the employer,” says Elefsen. There could be up to 50 women at a time in the apartments.

“The living quarters were primitive, to say the least, and the shared spaces were cramped,” recalls Thoroddsdottir. “But there were no curfews for women, and men were allowed to visit any time.”

The rooms of the Róaldsbrakki, as part of the Herring Era Museum, have been restored, and the decor and personal items donated either by the former herring girls or their families.

Without the herring girls there, the rooms look cozy, not cramped, with painted bunk beds, an iron and ironing board left out. Skirts, cotton shirts, slips, and bathrobes hang in the open closets. In the kitchen are the coffee urns and teapots, flour and sugar tins, cups, toaster, a floral-painted bread box. Spread out on top of several portmanteaus are album covers of Nordic troubadours of the time—and also of Harry Belafonte and Elvis Presley. The wall calendar is left open to a moment when the museum decided to make time stop: August 1941. It looks as if the girls temporarily stepped out and will be coming back—and the sea will be boiling with herring again.

The herring girl era ended in the summer of 1969 when the boats came back empty.

“The herring was fished up,” says Helgi Thorarensen, professor of Aquaculture and Fish Biology at Holar University in Iceland. “The disappearance of the herring caught everyone by surprise. And it was not until later, in the 1980s, that Iceland began to implement proper fish management and farming.”

The herring girls left overnight. “It was very difficult for many in Siglufjörður,” says Thoroddsdottir. By then, she had moved away too, though came back often to visit her parents. She moved back permanently later in life, and she sees the town changing all over again.

“Most of it relates to the opening of the tunnel that connects Siglufjörður to the Northeast of Iceland and Akureyri. The tunnel made things possible with new investments in the town. We now have a brand-new hotel and new businesses. Tourism has increased here, but it is not a new herring adventure.”

At 81, Thoroddsdottir still sees some of her old friends she worked with on the piers. “I do keep in touch with a few of them,” she says. “We meet regularly to chat and share old stories.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook