How a Team of Reenactors Helped Solve a Revolutionary War Mystery

Led by archaeologist Meg Watters, the Parkers Revenge Project reconstructed a crucial battle on the first day of the Revolutionary War.

In June of 2014, archaeologist Meg Watters led a team of five Revolutionary War reenactors through a forest in Minute Man National Park, on the edge of Lexington, Massachusetts. It was damp out, and the reenactors had traded period garb for rain slickers, hiking boots, and metal detectors, which they slowly swept over the ground.

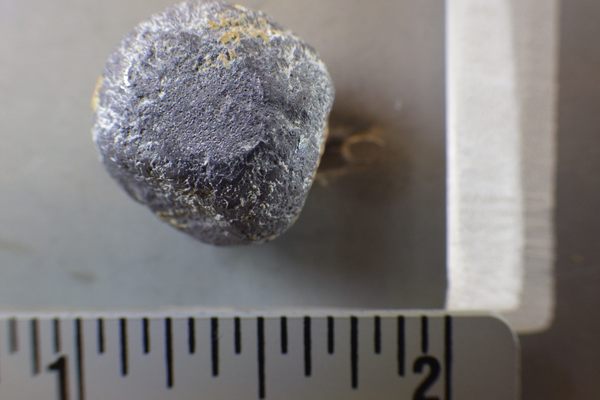

Their first few dozen pings were all useless—cans, bits of wire—but eventually, they found what they were looking for: a gritty, rusted sphere, about the size of a large blueberry. “We actually hit a musket ball,” says Watters. “It was like, alright! Here we go!”

Two years later, Watters and her team have successfully used that musket ball—and 31 others—to recreate Parker’s Revenge, a legendary but little-understood skirmish that took place on the first day of the Revolutionary War. A few weeks ago, the Parker’s Revenge Historical Project released their final report on the battle, capping off a multi-year project and solving a centuries-long mystery.

All Americans are conversant in the better-known events of those first Revolutionary days—Paul Revere’s ride, the “shot heard ‘round the world,” the bloodshed at Lexington and Concord. Parker’s Revenge is more of a deep cut. It lasted only ten minutes, and just one first-person account of it exists, a spare description from a militiaman named Nathan Munroe. (“We met the [British] regulars in the bounds of Lincoln, about noon, retreating towards Boston,” it reads, in part. “We fired on them, and continued to do so until they met their reinforcements in Lexington.”)

But those who do know about the battle hold it up as an exemplar of Revolutionary courage. Captain John Parker, who had brought 77 men to that morning’s Battle of Lexington, lost 18 of them to death and injuries before heading after the retreating British. “So he takes 20% casualties, patches up his men, and makes the decision to march after this force, which was ten times the size of his,” says Robert Morris, President of the Friends of Minute Man National Park. “This was just an incredibly heroic effort that we wanted to document, research, and preserve for future generations.”

Thus far, doing so has involved three years of multidisciplinary research, with Watters and her team digging through archives, data, and dirt to piece the battle together. The first step was finding the battlefield—although the general area was known, everyone had different ideas of where exactly the fight took place. Watters sifted through historical documentation, taking into account everything from oral reports of the day’s other fights to tax records and land conveyances.

She also brought in an ecological design expert, who pointed out how the landscape likely differed 240 years ago. Slowly, a picture of the past began to emerge: what is now new growth forest and a wetland was pastures, meadows, and an orchard. There was a barn in one spot, and a road in another.

One they had narrowed down the setting, Watters and her team of volunteers went over 25 acres of it with sophisticated metal detectors. In response, several distinct eras of history reared up to meet them. For a large chunk of the 19th and 20th centuries, the area had been filled with houses, and the ground was covered in the debris from hundreds of lives. Nails from 1890 mingled with beer can tabs from 1970. After a thorough sweep, they had found “thousands of pieces of trash and 29 musket balls,” Watters says.

Next, a revolutionary ballistics expert carefully examined each musket ball to determine whether it had been British or Colonial. They mapped where the balls had fallen, and did what are called “viewshed analyses,” where they determined what parts of the land would have been visible by a Colonial soldier marching on foot or a British officer on horseback.

Researchers made use of a battlefield analysis strategy, known as KOCOA, that focuses on what fighters think about when they see a landscape—“things like, where would be a good place to take cover? What were the obstacles? What, from their perspective, was the line of fire, the line of sight, and the key terrain?” Watters explains.

When they had gathered all the data, they held what Watters calls a “military tactical review event.” Ecologists, historians, veterans, and military commanders pored over the available information, walked the field, and discussed what, exactly, needed to have happened for the pieces to fit together in the way that they did.

“We determined what happened in the field, based on everyone’s expertise,” Watters says. “All tied together by the archaeological artifacts—by those musket balls that were dug out of the ground.”

The story they found goes as follows: after the Battle of Lexington, Captain Parker and his men came to the boundary of the town and set themselves up at a bend in the road, at the edge of a large woodlot. There, hidden by trees and boulders, they waited for the British, who were retreating from Concord towards Boston.

As the British approached, they sent a vanguard ahead to engage —but before they could organize themselves, the Lexington militia fired, one shot each. They then retreated over a small hill. The British fired at their backs. In this way, Parker had his brief revenge.

Within this broad summary, small details paint an even more human picture. The placement of one Colonial musket ball means a militiaman probably dropped it as he retreated. Distribution of fire suggests that some soldiers ran more quickly than others—as one army historian commented, “The young guys would have taken off fast while the older fat guys would have taken more time to get their things together and move.”

Now that the initial research is complete, Morris says, it’s time to tell the public this story—to reincorporate Parker’s Revenge into the park itself. “This may include things like restoring colonial stone walls and rehabilitating a colonial-era orchard” to return the land to a historically representative state, he says. Walkways may lead visitors through the battlefield, pointing out the positions of both troops. Those telltale musket balls will get their own display case in the lobby.

One group has already benefited from the new information: the reenactors. Representatives from 12 different reenactment groups—Redcoats and Minutemen alike—volunteered on the project, helping with everything from site preparation to metallic surveying. On Patriot’s Day of this year, reenactors were able to play out Parker’s Revenge exactly where it took place 241 years ago, and future run-throughs will be able to incorporate even more detail.

“That’s kind of an emotional thing for reenactors, to actually be standing where people stood,” says Morris. Ed Hurley, one of the volunteers, felt transported back centuries: “Each time [I found a musket ball] my first thought was of the individual who had last touched the ball,” he is quoted as saying in the project report. “Who was he? What was he feeling?”

Archaeology can’t quite tell us that. But thanks to the renewed dedication of Hurley and others, the land will keep giving up the secrets it can. “A few of [the reenactors] have since gone on to be crazy archeology metal detecting guys,” Watters says. If there’s more history out there, they’ll find it.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook