The Green Curtain

Germany’s Iron Curtain is now the Green Belt, but turning the old border into a haven for wildlife has taken much more than just letting it be.

For most of its length in Germany, the Iron Curtain was actually a steel fence, and Kai Frobel could see it from his childhood bedroom in the West German village of Hassenberg. The barrier, more than 10 feet tall and made of a kind of mesh specially designed to offer no finger-holds to would-be escapees from East Germany, snaked through the Steinach Valley. It divided the landscape into the domains of documents. On one side, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. On the other, the Warsaw Pact.

The border made a surreal neighbor. Frobel remembers flares shot off at night to expose potential escapees, and the occasional distant thump when a stray deer set off a landmine. Other encounters with it were more disturbing. Frobel’s father, the local doctor, was once called to treat a farmer maimed by an East German landmine that had washed into his fields during a seasonal flood. When Frobel was 16, he stood on top of a car and watched as East German authorities evacuated and leveled an entire village that was too close to the fence. Plumes of dust drifted into the sky as house after house was knocked to the ground.

Equipped with trip-wire machine guns and patrolled by guards with orders to shoot to kill, the border was called the “Death Strip” by West Germans.

For decades, it was a fact of life, so entrenched that, for those who grew up along it, it seemed it had always been there. Though in retrospect it was short-lived—first sealed in 1952 and dismantled in 1990, soon it will have been gone almost as long as it existed—to those living in its shadow in the 1970s and 1980s it seemed built for the ages. Frobel, an avid amateur photographer, has plenty of landscape shots in his archive, but almost none of the border itself. “I just assumed it was always going to be there,” he says now.

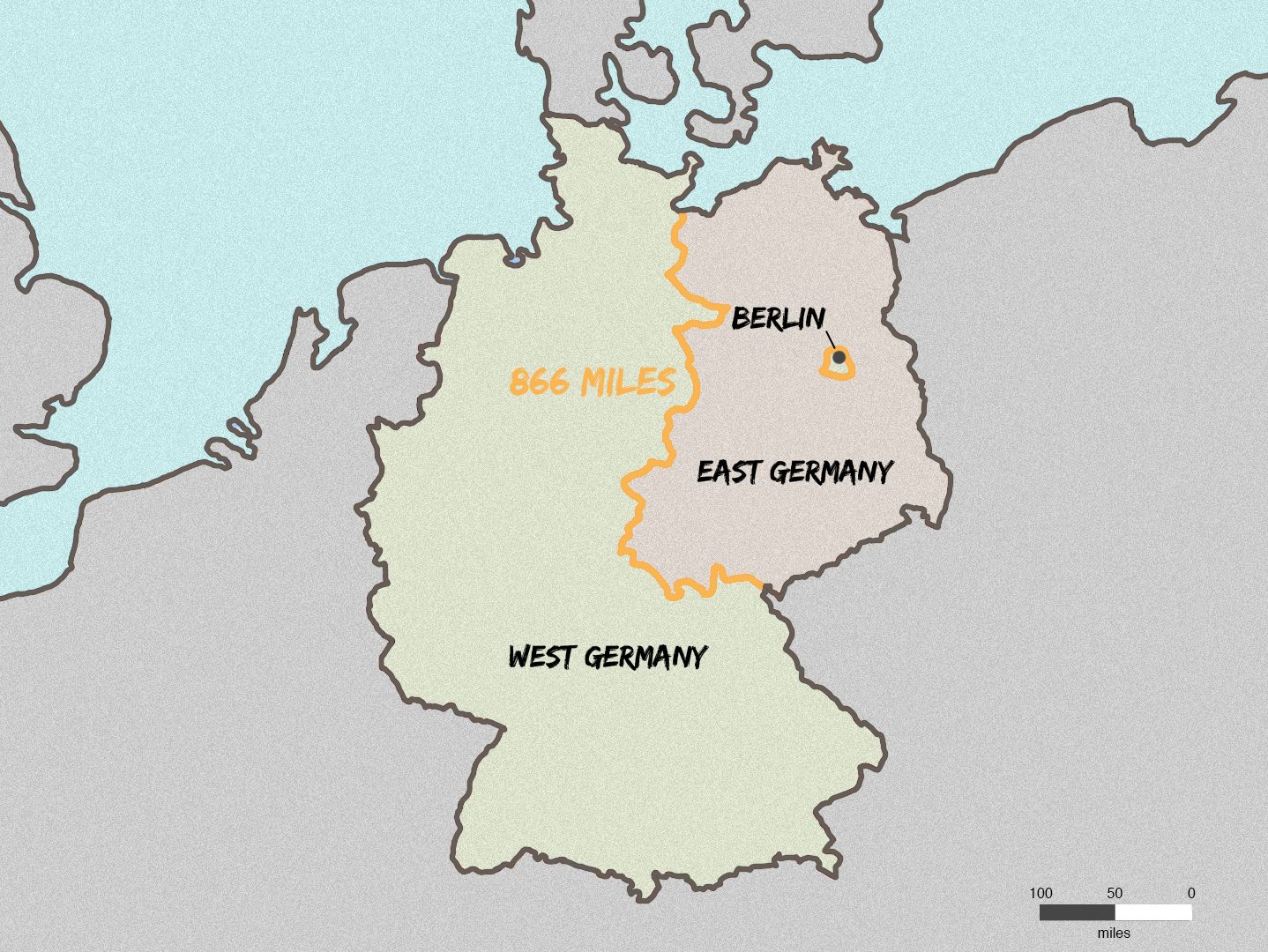

The 866-mile border was one of the most recognizable and politically charged changes to the landscape following World War II. But all of West Germany was transforming, too. As it had in many parts of the world, industrial agriculture was turning what for millennia had been a patchwork of pasture, fields, and forest sprinkled with small towns into a much more uniform landscape—a monoculture of barely distinguishable crops.

In a twist of fate that reverberates decades later, the land on the Death Strip and some areas around it were protected from the plow and the combine. “In the ‘70s, the landscape was drained, cleared, planted,” Frobel says. “The border was the last refuge.”

In the 30 years after the crumbling of East Germany, known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), the border between east and west has transformed again, into the Grünes Band, or Green Belt, a swath of protected land that runs from the Baltic Sea in the north all the way to the mountains of Bavaria in the south. It connects more than 100 different types of habitat, from grasslands to marshes to forests. And the corridor—longer than the distance between New York and Chicago, but only about 50 to 200 yards wide; 68 square miles in total, a little bit less than Brooklyn—is home to a staggering 1,200 threatened species.

One part nature preserve and one part historical monument, the belt has inspired an effort to create a similar preserve along the length of the former Iron Curtain—which would cover well over 7,000 miles in 24 countries. It’s a remarkable shift in thinking. When it was built, the West German–East German border was regarded as an ugly scar, a physical reminder of the political division that ripped the country apart after the greatest armed conflict the world had ever seen.

The project has attracted its share of critics. Farmers who lived in the shadow of the Curtain for decades initially resisted the Belt, and many in Germany didn’t understand why valuable farmland should simply be set aside. It was seen in some ways as just a different border, invisible but just as implacable.

Slowly, since the Belt project began in 1990, attitudes have softened. Thuringia, the former East German state that has the longest stretch of the Green Belt on its borders—more than half of its total length—declared the area a national natural monument last year. (The grassroots project is a patchwork, too: Some segments have obtained official protections, others are owned by conservation organizations, and roughly a quarter is privately owned.)

In the ‘80s and ‘90s, the GDR was known—in West Germany, at least—for belching coal-fired power plants and little to no regard for its environment, or that of its sibling to the west. “The discourse in the early ‘90s was that the West had won the Cold War and the East committed ecocide,” says Astrid M. Eckert, an Emory University historian and author of West Germany and the Iron Curtain: Environment, Economy, and Culture in the Borderlands.

The truth was more complicated: In reality, both countries were polluters, but the border made East Germany a convenient scapegoat for West German politicians. Meanwhile, political repression made the development of a significant environmental movement in East Germany difficult. The idea of the Green Band, Eckert argues, was a convenient way for West Germany—in many ways the winner of the Cold War border stand-off—to put a positive spin on decades of mutual environmental neglect.

It worked. Now thousands of people hike along the Death Strip, which has evolved into a wildlife corridor with few parallels in Europe or the world. The idea that something of such natural value—let alone an ecological treasure on the scale of the Green Belt—could come out of decades of enmity is a dramatic shift in how people think of the border and consider its environmental legacy.

Unlike the demilitarized zone that still divides North and South Korea, which was drawn roughly along the 38th parallel, the former German border looks like it was drawn by an ant in search of food. Even from the ground, and it zigs and zags all over the place.

On a recent summer day, I met Frobel in Mitwitz. The town happens to be both east and west of the former East Germany, protruding into the twisting stretch of border between the German states of Bavaria and Thuringia like a wart. Now 60, Frobel works for the environmental organization BUND (Friends of the Earth Germany) and lectures on nature conservation at the nearby University of Bayreuth. He’s dressed for a nature walk in Germany, a drab vest over a short-sleeved shirt, with brown sandals over brown socks.

After cake and coffee at stately, moat-encircled Mitwitz Castle we zoom off in his car, along one-lane country roads. We’re just a few miles from where he grew up, and he knows the folds of the land here intimately. After a few minutes, he slows and makes a sharp right turn, onto a dirt track that takes us bouncing through a dense birch forest. “These trees are, maximum, 30 years old,” he says, slowing and stopping in a lush green field. Opening the door, he grabs a pair of binoculars and drapes them around his neck before plunging through waist-high grass buzzing with insects, and into a stand of trees still dripping from a morning storm.

He’s brought us to the bank of a small stream, which once actually marked the border between West and East. When Frobel was a boy, the stream had warning signs plunged into it every few hundred feet. But unlike most waterways in Bavaria, which had been channeled or diverted for agricultural purposes, this one was otherwise untouched.

The small waterway was a rare blind spot along one of the most fortified frontiers in the world at the time. Frobel knew that, when he slipped into the streambed years ago, he was invisible to the East German border guards in a bunker just a few hundred feet away. “It’s a big adventure, when you’re 13 or 14 and on the most guarded border in the world, the line between NATO and the Warsaw Pact,” Frobel says. “It was a really special place for me.”

By the 1970s, the border between East and West Germany was fortified by layer upon layer of security measures. Though East German propaganda described the fortified border as a way to keep fascists out, its actual purpose was to keep East Germans in. Few of them ever even saw the border itself: Ordinary citizens were heavily restricted from living or working within five kilometers (3.1 miles) of the border. All along its length, the design of the fortifications was identical. “It’s very German—once you figure it out, do it all the same,” Frobel says. First came watchtowers, regularly spaced three kilometers (1.9 miles) apart to give guards continuous sightlines. They were connected by a single-lane path made of concrete paving stones that ran the length of the border.

Next to that was a “control strip,” a barren dirt expanse 20 feet across that was regularly groomed to provide a clean palette for the footprints of any would-be crossers, fronted by a deep ditch lined with thin concrete slabs designed to trap vehicles charging at the border fence. Between that and the fence itself was a minefield sowed with, over the years, 1.3 million anti-personnel mines.

Then came the fence itself, supposedly unscalable.

On the other side was another tightly monitored buffer, between 30 and 300 feet across, that was officially East German territory. In all but the most remote areas, it was occasionally mowed or cleared of trees, but otherwise left fallow. This seeming “no-man’s land,” known to East German guards as “upstream territory” or “advanced sovereign territory,” was typically marked by no more than concrete posts, painted or labeled to mark them as East German. “Border tourists, who wanted to see the Iron Curtain or glare at communism, mistook the fence for the border,” Eckert says, and walked right up to it, into East German territory. Some of them ended up spending a scary night in East German jail as a result.

As a teenager in the area, Frobel developed into an avid bird-watcher. To hear him tell it, he spent some of the best moments of his youth ambling along the frontier, an awkward boy in green rubber boots, carrying oversized binoculars. “Everyone, on both sides, was armed, with loaded machine guns,” he says. “It was a strange feeling looking for birds between them.” Sneaking down into the streambed, he documented rare dragonflies and freshwater mussels that had mostly vanished from elsewhere in the country.

Frobel wrote his sightings up for a high school biology class, and they quickly attracted the attention of the local chapter of BUND, where he was a member. The organization enlisted him to help complete a larger-scale survey of bird breeding pairs in and around Coburg, the nearest midsize city. Of particular note were whinchats, a species once common in the German countryside that had all but vanished in Bavaria—but which Frobel had counted by the dozens, perched atop the border fence. “We could prove that in the whole Coburg area we had 110 breeding pairs, and 100 of them lived in the border area with the GDR,” Frobel says. As Frobel and a team of teenage volunteers spread out along miles of the Bavarian border strip, the findings were the same—avian biodiversity was highest along the border.

On the other side, East German bird-watchers were noticing similar phenomena. Black storks, an indicator species that hadn’t been seen in central Germany for nearly a century and a half, were spotted in East Germany in the 1980s. Critically, these birds were seen in a breeding pair, settling down and not just passing through. But documentation of sightings like this was sparse and scattered. The division of the country made it almost impossible for amateur naturalists or academics to share information, and access to each side was severely restricted or even impossible from the other. The few observations came from border guards themselves, some of whom kept bird tallies to stave off the boredom of wall-watching.

Of course, it was not a haven for every animal. There were those deer, for example, who set off mines so regularly in the 1960s that yet another fence was erected along many parts of the border to keep them out. “It was great for birds,” Eckert says, “but really sucked for mammals.”

When early results of Frobel’s survey were announced in 1980, activists used them to pressure the West German government to pass stronger environmental protections. It was the height of the Cold War, and the idea that the border might one day be anything other than what it was, or that it could be considered a refuge of any kind, was unthinkable. “The argument wasn’t that the GDR was preserving nature, but that it was shameful for Bavaria that species needed the Death Strip to keep them alive,” Frobel says.

Meanwhile, BUND started buying up parcels of land near and straddling the border, hoping to use its protective shadow to create safe spaces for threatened species. Frobel got a degree in ecology and went to work for BUND’s Bavarian branch, as both a researcher and a lobbyist. He began corresponding with bird-watchers in East Germany, hoping to share sightings. Mystified, East Germany’s secret police compiled a 100-page dossier on him.

Frobel was as surprised as anyone when the East German government lifted travel restrictions on its citizens on November 9, 1989—a momentous Thursday, as it turned out. With the sudden utterance of an East German official in response to a journalist’s question, the elaborate fortifications that had run through Germany like a scar for decades were suddenly irrelevant. Late that night, crossings through the Berlin Wall—not part of the longer border, since it just cordoned off a West German enclave deep within East Germany—were opened. By Friday morning East Germans were flooding into Coburg and other Western cities close to the wall to get their first glimpses of life on the other side—4.3 million, a quarter of the country’s population, in the first four days alone.

When Frobel got to work at BUND the following Monday, his boss told him to write letters to anyone they knew in East Germany who might have connections to the environmental movement, with invitations to a meeting a month later. Frobel came up with a couple dozen names, and sent the invitations out that day, with a note to pass the invitation along to anyone else who might be interested.

A month later, Frobel arrived at the countryside hotel they’d picked for the meeting to find the parking lot packed with East German Trabants, renowned for their shoddy construction. Waiting for him inside were 400 East German environmentalists. All day they discussed how to take advantage of the moment. Armed with West German data and reports from the East Germans, Frobel advocated for a nature preserve covering the length of the border. The idea, at least, of the Green Belt was born.

Thirty years later, in a spare office on the edge of Coburg, a half-hour drive to the west of Mitwitz, Stefan Beyer unrolls a detailed contour map to show me what’s happened since the border became a relic.

Beyer, a tall, lanky biologist, works on a regional conservation project with BUND and others. After German reunification in 1990, he explains, most of the border fortifications were hastily torn up and scrapped. The area was cleared of mines. Green Belt advocates lobbied the federal government not to sell off unclaimed portions of the old border, which kept much of the non-private land untouched until it was bought up by BUND or given protected status by the government.

As the Green Belt took shape, organizers envisioned it as a wild place in the middle of densely populated Germany. “There was this attitude at the beginning that ‘Nature was raped by border troops, and now we can let nature take its course,’” Beyer says. That, and the complications of trying to secure funds and more of the land, resulted in a hands-off policy along much of the former border.

But nature is never quite so simple. Instead of thriving, the species that had flourished in the 1970s and 1980s unexpectedly began to decline. In many spots, the buffer zone along the former border was soon choked with bushes and saplings. It looked clotted and overgrown, no longer ideal habitat for the species there who needed the open habitats the border guards inadvertently created.

Soon advocates realized the border hadn’t preserved some primeval natural order. Rather, it was another in a long line of human interventions that created and maintained an open landscape capable of supporting a broad range of birds, bugs, and other creatures.

In the distant past, some researchers think, Europe wasn’t covered by unbroken forest. After massive continent-spanning glaciers melted away around nearly 12,000 years ago, fires helped create a mixed landscape of open meadow and forest, with large animals—from mammoths and herds of wild horses to massive wild cattle called aurochs—stomping and grazing on saplings, and keeping encroaching forests at bay. The effect is similar to how elephants and other large mammals have shaped the African savanna. By the time those species were wiped out or domesticated—aurochs, enormous ancestors of modern domestic cattle, finally went extinct in the 17th century—humans had taken over. For millennia, small-scale farmers and herders managed forests and fields. This traditional agriculture created a mix that mimicked the original postglacial landscape and supported a wide range of different species. Farmers were—coincidentally, perhaps—shaping the ecosystem in much the same way the megafauna had, so the theory goes.

Through its structured layers, the intervention of border guards, and, strangely, landmines, the border had created a kind of glimpse into Germany’s ecological past, at least in a small way. All it took was an international standoff of epic proportions. Now these lessons are being applied to structuring and maintaining the Green Belt. “Some species need more open space. When you don’t do anything, the Belt grows over and its value as a nature preserve sinks,” Beyer says. “Now we’re learning that when you want to maintain the landscape the border troops created, you have to actively intervene.”

Known as rewilding (in this case Pleistocene rewilding), this increasingly popular approach to conservation is not the same as letting nature take its course. The process is actually carefully managed, at least initially, and aims to restore some semblance of the natural processes—and players—shaping the landscape before humans edged out megafauna, and before patchworks of farms and forest were subsumed by the global economy.

BUND, along with other conservation groups and federal and state ministries, is spending more than $10 million in Bavaria and Thuringia in the coming years to wind the clock back to the final days of the GDR—and much, much further. On the map, Beyer points to spots along the Green Belt where a rugged breed of aurochs-like cattle, capable of staying outside year-round and with an appetite for tough bushes and saplings, is being used to control growth along some areas.

“Germany was never 100 percent forest,” Beyer argues. “In the past, parts of it were kept open by these big creatures, and we’re trying to recreate those open areas, to approximate these early landscapes.”

So far, it’s working. In high summer, the former border area around Mitwitz is unmistakable—a stripe of intense green coursing through paler farm fields. There are birch forests, thick stands of bushes, and lush—albeit narrow—meadows threaded through it. Cyclists ride by, singly and in small groups, on a maintained concrete path. The stream where Frobel once hid as a boy is still shrouded in greenery, but with no bunker or guards nearby to watch out for. “Quiet places like this are so important,” Frobel says, going quiet himself. “And rare.”

As the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall approaches, the Green Belt has taken on yet another dimension. It’s the largest physical remnant of the Cold War left in Germany, and alongside nuclear pollution and the Korean DMZ, one of its most potent artifacts.

As Frobel drives back to the castle, he slows and pulls over in the middle of a field. Under the shade of a small tree there’s a stone memorial, with a simple inscription: “Here stood the village Liebau. Demolished in 1975 by order of the SED regime.” I realize it’s the village Frobel watched ground to dust when he was a boy. (The SED was the Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschland, or Socialist Unity Party, that ruled East Germany.) We stand in silence for a minute.

As we drive on, Frobel tells me about a trip he recently made to South Korea, where he’s been consulting on the future of the demilitarized zone. “They’re already planning to create a park when reunification happens,” he says. “We tell them, ‘For God’s sake, leave the fences and watchtowers standing so you can tell future generations what it was about.’”

There’s none of that here, just farms, fields, and forest. But look carefully, from a high enough vantage, and you can see the outlines of the past, a jagged strip through the valley. What started as a conservation project has become something else. “It’s a living, ecological monument to this rip through Germany’s fabric,” Frobel says, a wound healed over in green.

You can join the conversation about this and other Border/Lands stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook