The Final Ride of the Mail Robots

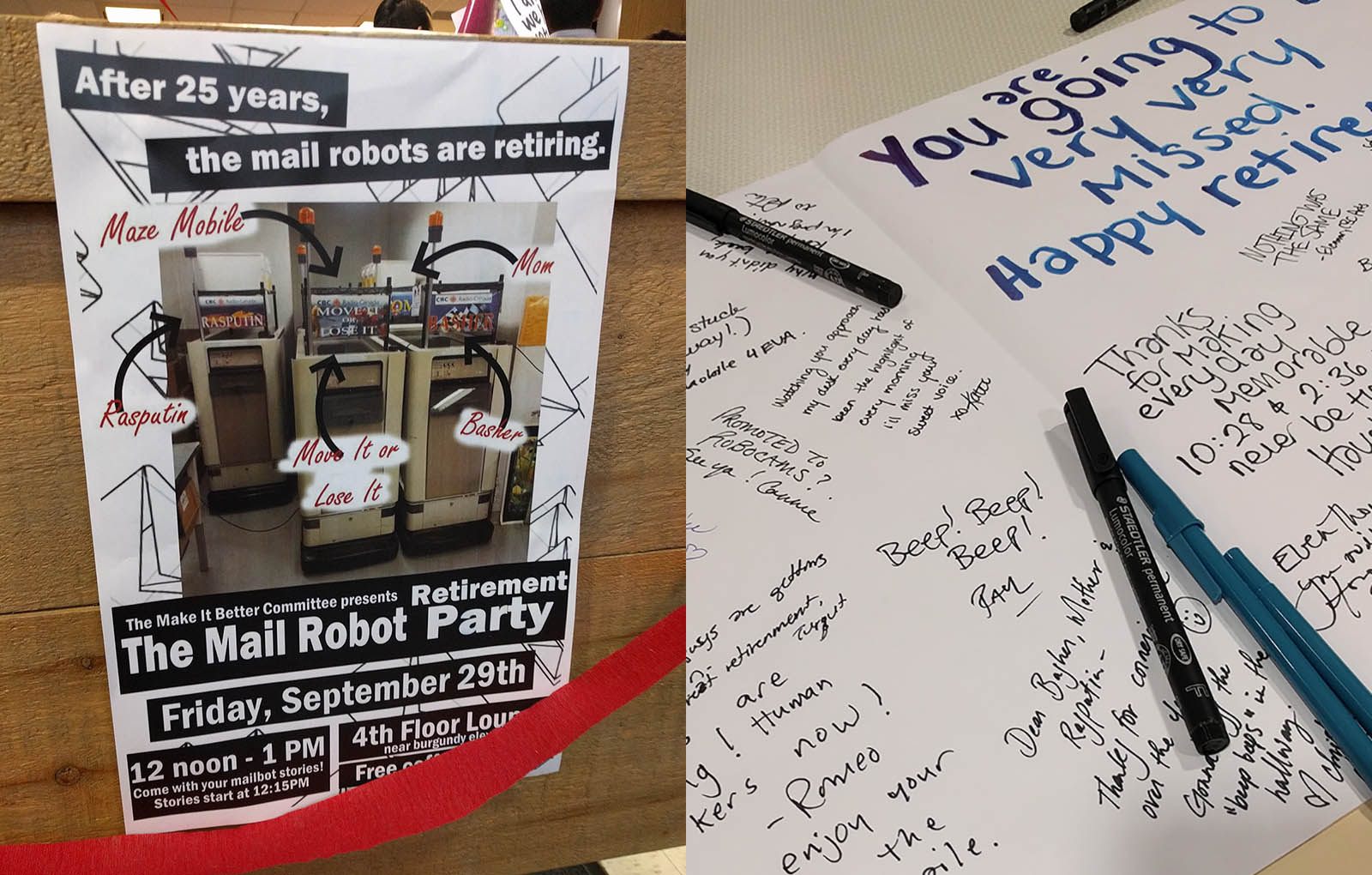

On the scene of a retirement party for Rasputin, Mom, and three other Mailmobiles.

In September 2017, there was a retirement party at the headquarters of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Canada’s national broadcaster. After a quarter century of loyal service, five coworkers were moving on.

In many ways, it was like most retirement parties. A group of colleagues gathered in a kitchen, with cake, swapping stories and memories. There were speeches, laughter, and tears.

But what made this party unusual was that the retiring colleagues weren’t people. They were robots. Mail-delivering robots, made under the brand name Mailmobile.

In 2017, most people know about Mailmobiles thanks to FX’s hit Cold-War period drama The Americans. Over the show’s past five seasons, the FBI’s mail-delivering robot has been witness to flirtations, schemes, intrigue, and even murder. It’s been kicked and shouted at and praised. It even has its own Twitter account.

What you might not realize is that, between the late 1970s and when they went off the market in 2016, roughly 4,000 Mailmobiles were delivered to North American offices, according to Robert Moskin, implementation manager for Dematic, the Mailmobile’s latest (and final) manufacturer. Some of them are still in service.

The Mailmobile stands about four feet tall, two feet across, and six feet long. It is shaped like a rectangle that tapers slightly as it goes to the top. It’s heavy and metal, and filled with shelves for envelopes. The top of the robot usually carries bins for parcels. It beeps to tell you to get out of the way as it glides slowly through the halls.

The technology behind the Mailmobile was created in the late 1970s in the labs of the Lear Siegler corporation, manufacturers of the Learjet. Chicago’s Sears Tower was the first office building in the world to have one. In 1980, Lear-Siegler’s Mailmobile business was acquired by Bell and Howell.

Moskin knows the Mailmobile as intimately as anyone on Earth. He’s spent the last 35 years travelling North America, overseeing the installation of Mailmobile systems, first with Bell and Howell, and then, after a buyout, with Engemin Automation, and most recently, following another buyout, with Dematic.

“It’s fundamentally a labor-saving technology,” he says.

The early Mailmobiles functioned by following a path of chemicals, visible only under ultraviolet light, laid on the carpet of an office building. The UV sensor under the machine read the guidepath, telling the machine where to go. (Later models used magnetic, and then laser guidance systems.) A second code sensor read chemical markings that would tell the machine when to stop or even when to call an elevator.

“There’s an elevator supervisor product [in the Mailmobile],” Moskin says. “It sent radio signals that pressed the ‘car call’ and ‘car send’ buttons, like you and I would walk up and press the button, but with a radio frequency. Once the door opened, the machine goes into the elevator, usually the freight elevator, and then backs out on its floor.”

What’s really amazing about Mailmobiles, though, isn’t the technology. It’s the way people relate to them. They were designed to replace people. And yet, people love them.

Chris Berube was a producer at the CBC in the early 2010s. He says his initial reaction to the robots was, “this is what people thought the future would be like in the ’70s.”

He adds that, while he didn’t always think his robotic colleagues were the most efficient at their job—they would sometimes get stuck behind pillars or collide with slow-moving staffers—he did come to see them as friends, and even confidants.

“They are so inefficient and keep bumping into stuff, but they’re charming,” he says. “If I was having a bad day at work, I’d talk to them.”

That was by design, according to Moskin. He says that when Bell and Howell first began rolling them out, the company wanted to make people feel like the robots were part of the team.

“We promoted that,” Moskin says. “The idea was to make it a friendly machine. When the Mailmobile was introduced, we used to encourage companies to have a ‘name the Mailmobile contest.’ Sometimes it’s an acronym, like ‘MOM, Mail on the Move,’ sometimes it’s a funny name, sometimes it’s George.” As for the retiring CBC robots, their names were Basher, Rasputin, Maze Mobile, Move It or Lose It, and, yes, Mom.

The decline of the Mailmobile has happened in parallel with the decline in mail. As the volume of mail falls, so too does the need for a robot to cart it around the office. The exception, according to Moskin, is insurance agencies, which still deal with massive amounts of paper.

That said, the Mailmobile lives on in the form of Dematic’s Packmobile, a version of the Mailmobile built to carry heavier loads.

“You can get models that carry parts around a factory,” says Moskin. “You can get models that are essentially a driverless forklift. Machines that carry specimens around medical laboratories.”

The Mailmobiles also live on in the hearts of the human coworkers. After all, it’s hard to imagine five other co-workers who, in a building with thousands of employees, could get a few hundred people to drop by for a last-day selfie and a few words of farewell.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook