A Peek at Famous Readers’ Borrowing Records From a Private New York Library

Thanks to carefully maintained circulation info, we know when Alexander Hamilton checked out Goethe.

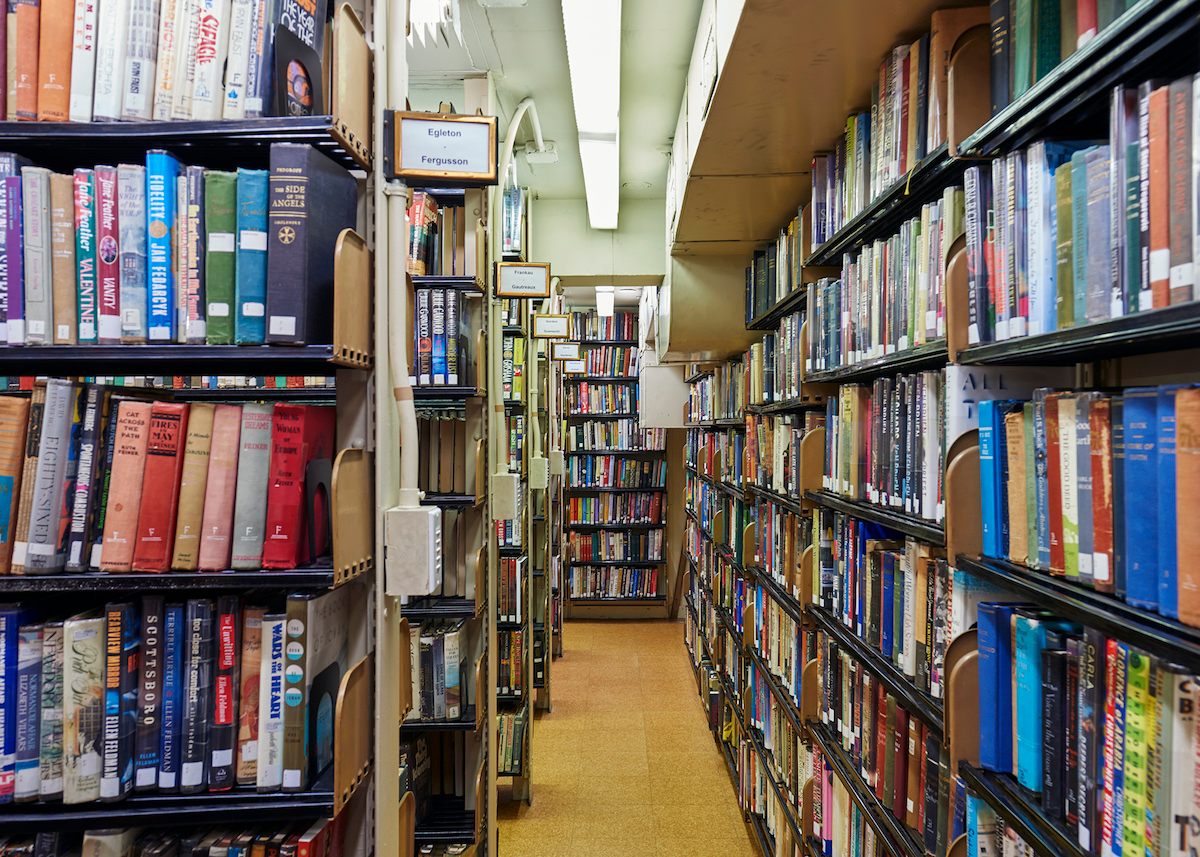

The New York Society Library, a subscription library now located in a prim townhouse on East 79th Street, has been squirreling books away since 1754. Today the collection occupies nine stacks, and like any library, it can be bit overwhelming if you don’t know what to read. But the Library’s archive offers an unusual book trail to follow: the borrowing histories of its readers past.

Until the New York Public Library was founded in 1911, subscription and circulating libraries were the norm in New York. Eighteen subscription libraries remain in the United States today, and while all charge a membership fee, only some allow the public to use their collections for free. Others, like the The Library Company of Philadelphia, have survived by transforming from libraries with circulating collections to non-circulating scholarly research libraries.

The Society Library has survived in part because New York is a city of readers and writers who have been willing to pay the annual fee, like a gym-membership for the mind. While anyone can walk in and ask for something to read in the Reference Room, only members have borrowing privileges and access to the stacks, as well as electronic resources, access to reading and workrooms, and the children’s library. Past members on the roster include Aaron Burr, Alexander Hamilton, Washington Irving, Herman Melville, Henry James, Edward Steichen, Willa Cather, P.G. Wodehouse, W.H. Auden, Djuna Barnes, George Plimpton, Malcolm Cowley, John Dos Passos, Lillian Hellman, John Cheever, Barbara Guest, Lewis Mumford, Helene Hanff, Roald Dahl, Leonard Bernstein, and Shirley Hazzard.

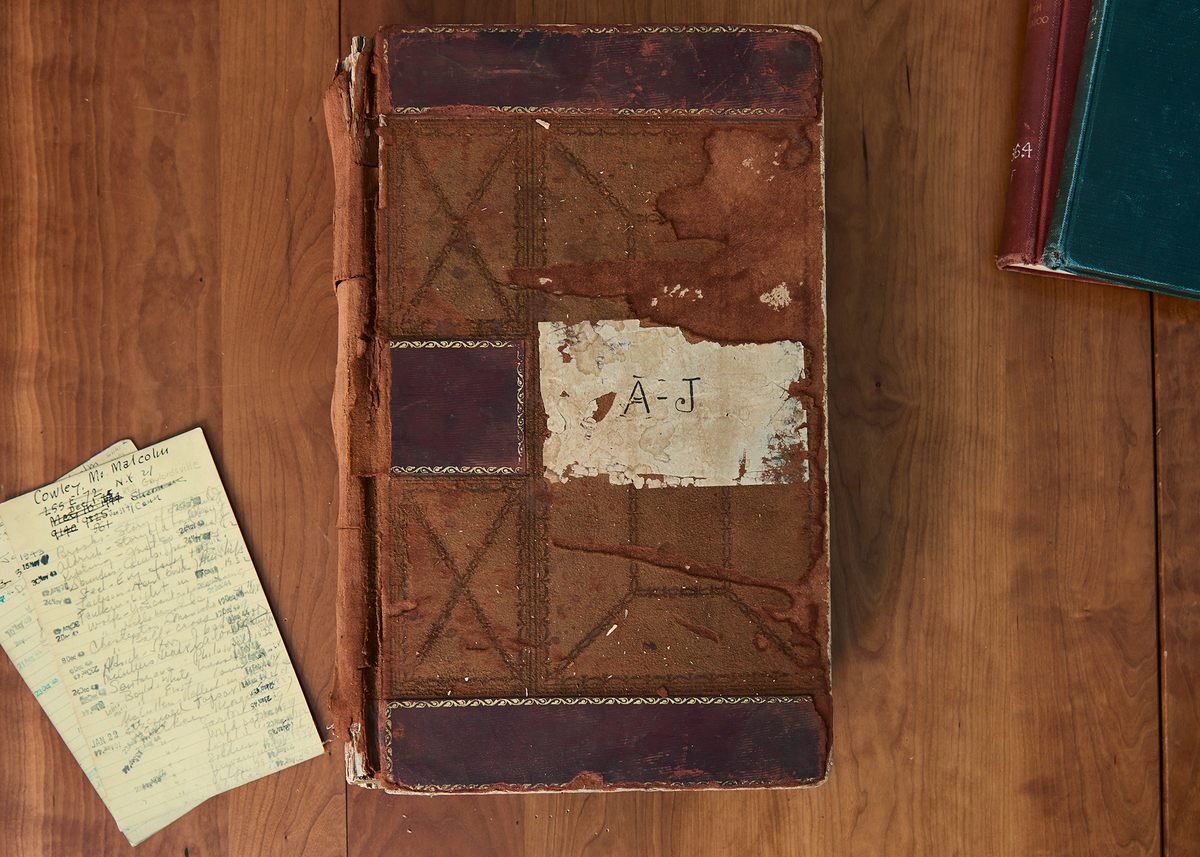

The Library has preserved the circulation records of its membership with a few small gaps, so readers today can work their way through the collection by following the breadcrumbs left behind by readers from the 18th to the 20th century. (Privacy laws prevent the preservation of such records today.) The first decades of records were lost during the Revolutionary War when the British occupied New York, so the earliest records date to 1789. That year the Library reopened in Federal Hall, the meeting place of the first U.S. Congress, and was used by 42 Congressmen and Senators. On April 7, 1790, 14 years before their famous duel, Hamilton and Burr both visited the Library: Burr was reading Voltaire, Hamilton was reading Goethe. Transcribed records from 1789 to 1805 are all available online at the Library’s City Readers project (which I worked on), with visualization tools to explore the collection and its use by members.

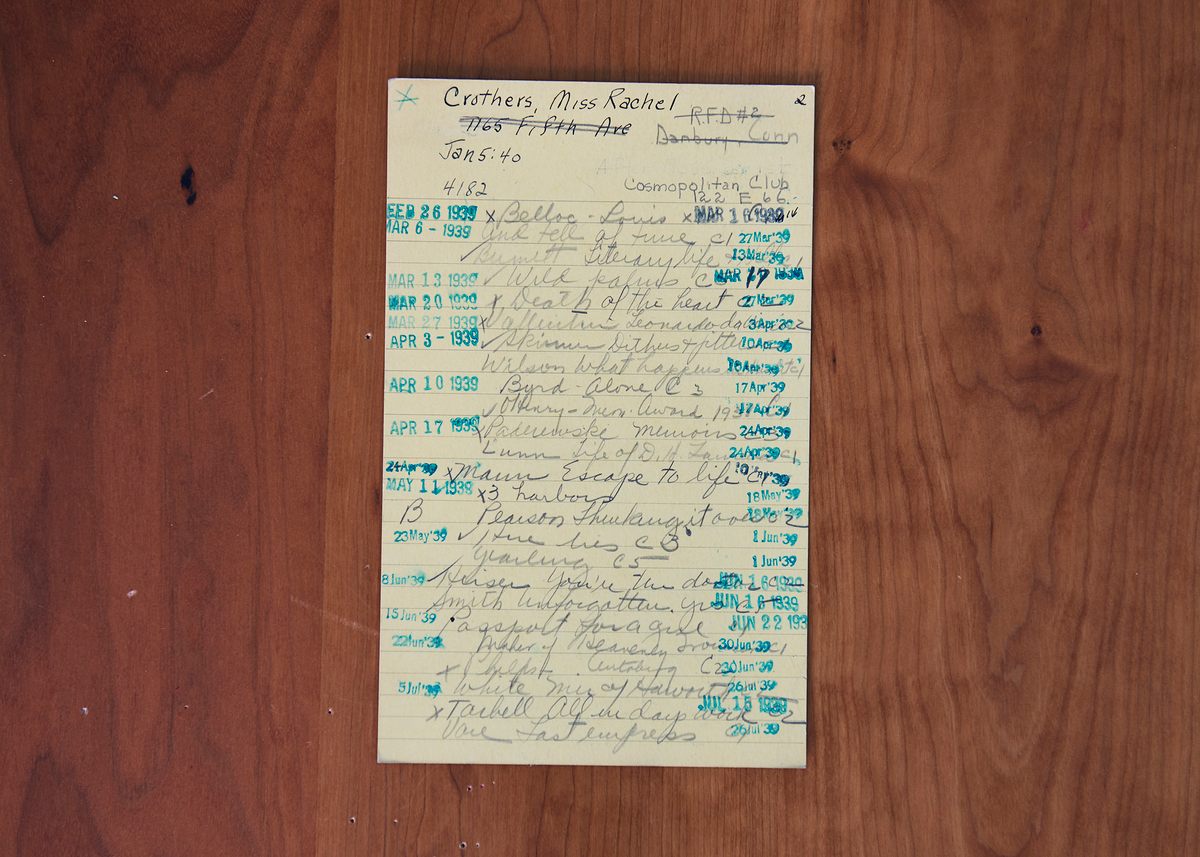

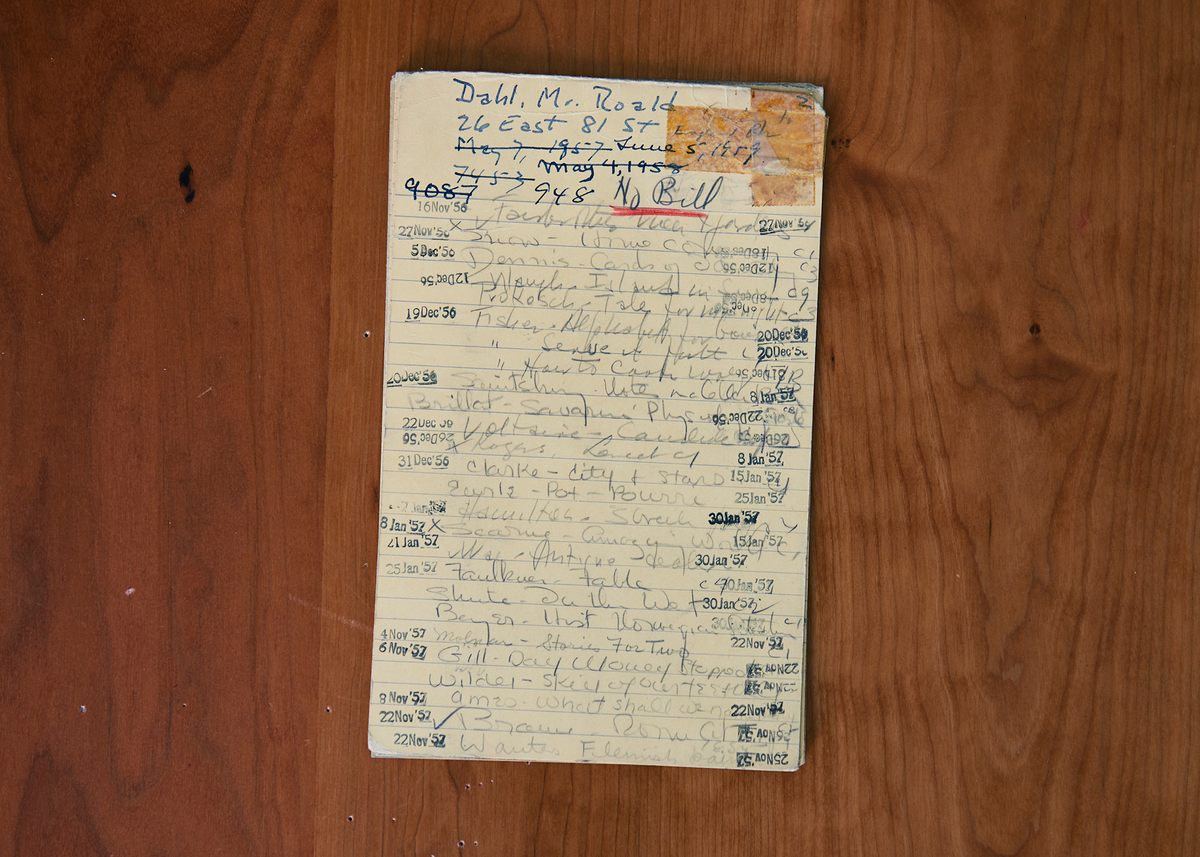

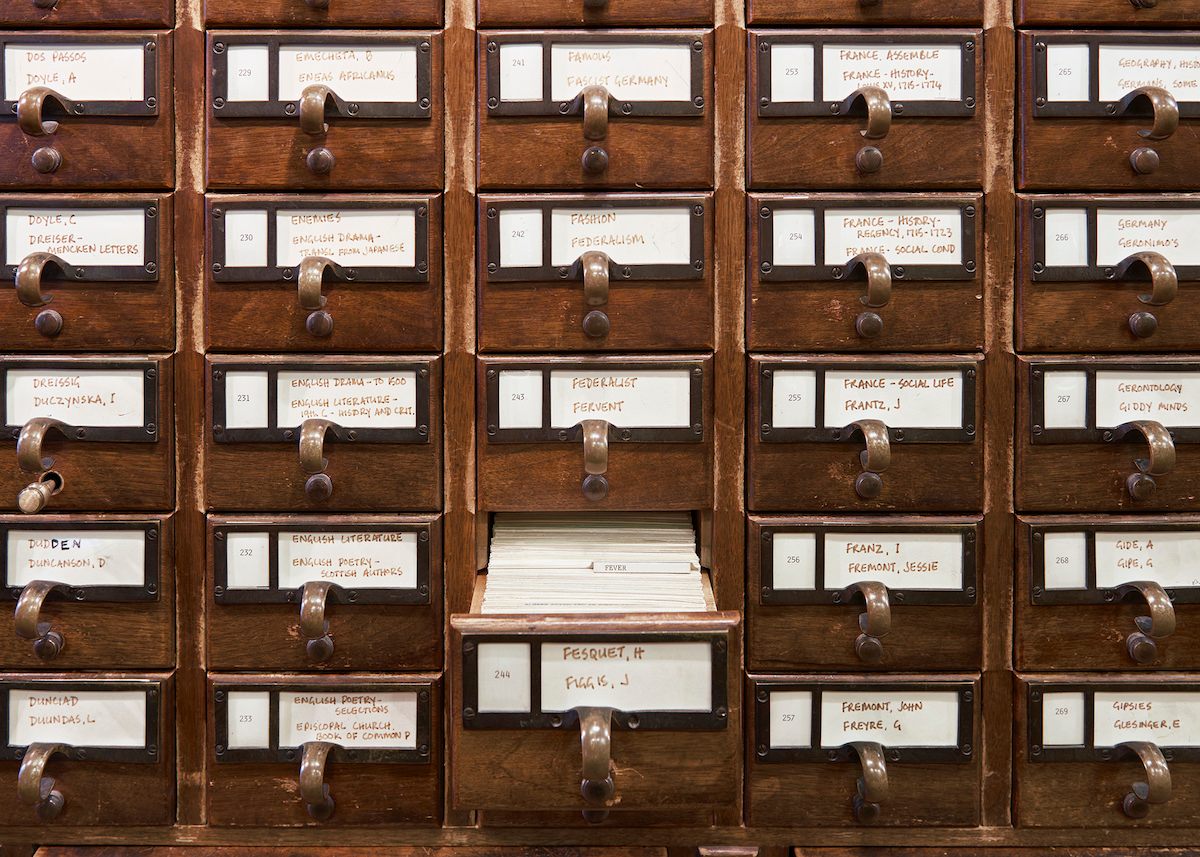

In the early 20th century, Library staff switched from big, blank ledger books to index cards for record keeping. Henceforth they archived cards only for “prominent” members, discarding the rest. The gap is major, but the surviving cards offer a lifetime of book recommendations.

The novelist, poet, critic, and journalist Malcolm Cowley, for example, borrowed several Faulkner novels in 1944, just two years before publishing The Portable Faulkner. Today we can read over Cowley’s shoulder by borrowing the novels and The Faulkner-Cowley File, a compilation of their letters from 1944 to 1962. Playwright Lillian Hellman read Faulkner there too in 1951. From 1946 to 1970 librarians filled eight cards, front and back, with the names of writers Chekhov to Voltaire scrawled in pencil.

Roald Dahl’s records track his reading for a full decade as well. He made weekly Wednesday visits to the Library in 1956 and 1957, borrowing mostly fiction, but a couple of cookbooks, too. Although he disappeared for nearly 10 months in 1957, he resumed his regular visits that November—the Library was part of his New York routine.

While the Library’s list of members-you’ve-heard-of is very white, it may have been more inclusive than its histories show. The Library has admitted women as members since it opened in 1754, while the Boston Athenaeum, a subscription library founded in 1807, did not admit women until 1829 and barred them from browsing the stacks at least until 1856. Between 1789 and 1805, 57 women were Society Library members. Little is known about readers of color there, probably because scholars have yet to dive into the countless unfamiliar names in membership rolls and circulation records in the archives. A recent book about Jeremiah Hamilton, New York City’s first black millionaire, is a promising discovery toward a more diverse history of the Library. Hamilton joined in 1856 and borrowed over 250 books in two decades of membership.

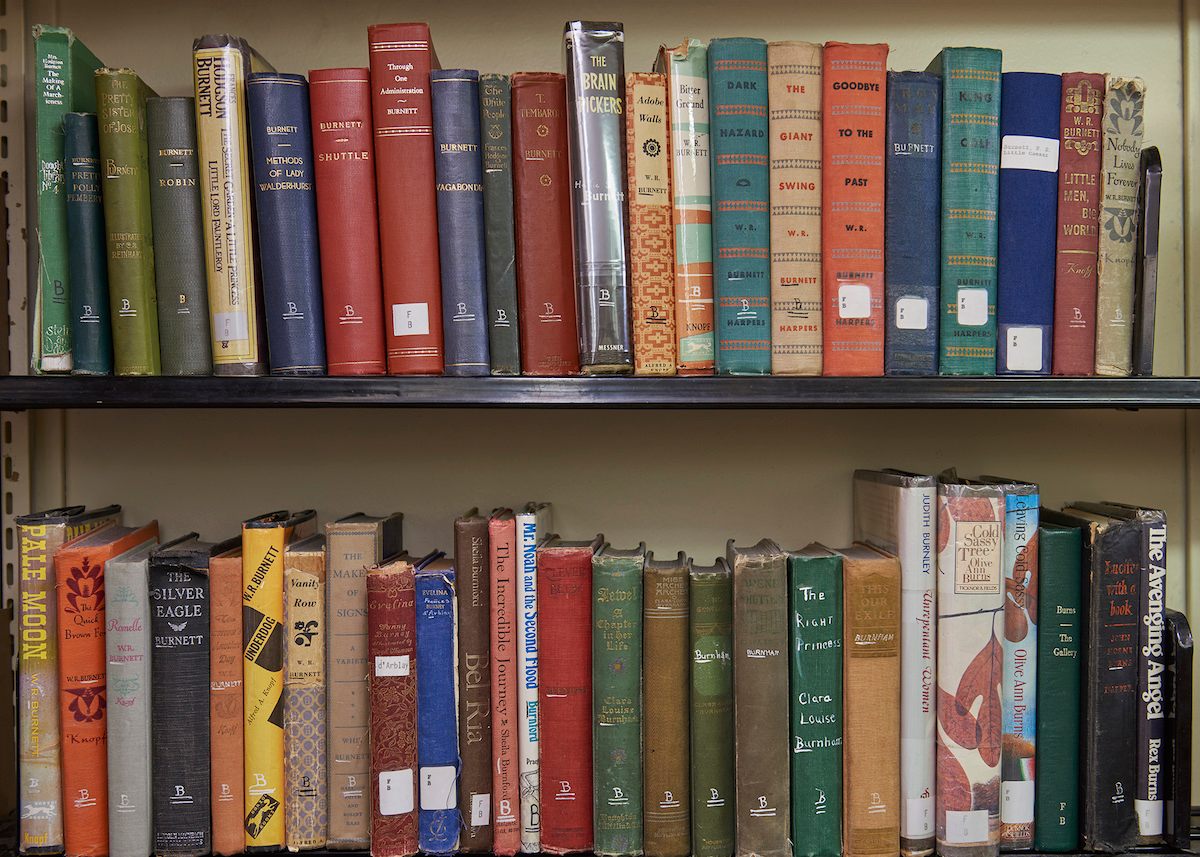

Recently, the Library has been a resource for writers exploring lives obscured in traditional histories. Janice Nimura and Pamela Newkirk have found inspiration and key references in the Library stacks for their books on Japanese women “volunteered” to study abroad in America and Ota Benga, a Congolese man kidnapped from his home and cruelly exhibited before crowds in the west. Society Librarians have always approached weeding conservatively. The stacks are filled with novels by long forgotten authors, and now superseded works of non-fiction still linger there, too. The MFK Fisher cookbooks that Dahl took home almost 60 years ago are still there, as are countless titles that other libraries have had to discard or send off site to make room for new acquisitions.

The Library has of course had to replace books over the years, but it still retains an aura of readers past in its collection. Often enough, the same book survives in the stacks to link readers past and present. (If you want to check, look for the acquisition date stamp in the gutter on the first page of text.) A book on whaling that Herman Melville kept out for 13 months while he was writing Moby Dick is still there, and so are the volumes of Voltaire that Burr borrowed.

*Correction: This post has been updated to include the correct borrowing card for Roald Dahl.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook