The Women Miners in Pants Who Shocked Victorian Britain

“The article of clothing which women ought only to wear in a figure of speech.”

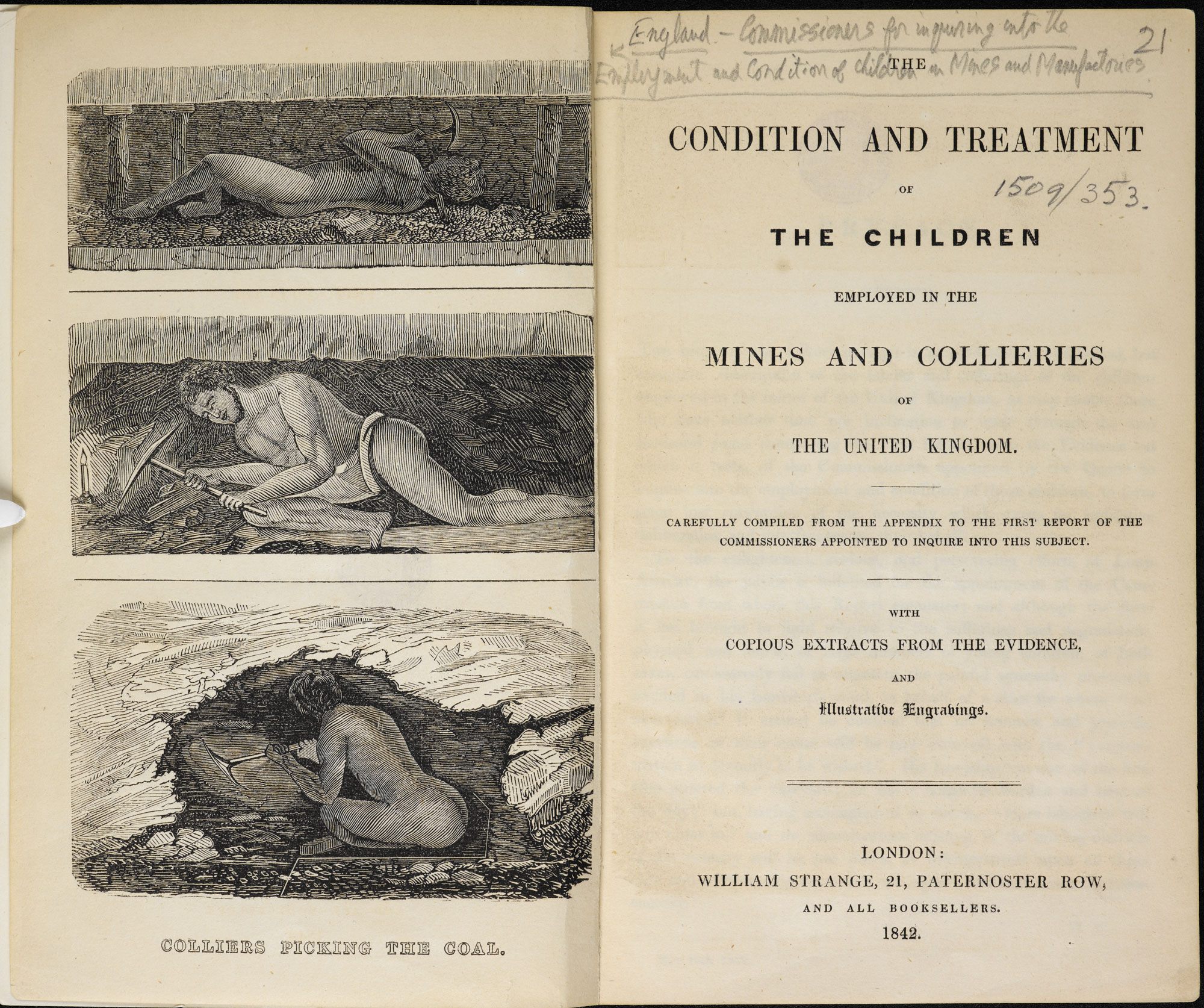

As part of an investigation into working conditions in mines, Sub-Commissioner Samuel Scriven went into a Staffordshire, Great Britain shaft in 1841 expecting to find a place of work. Instead, he descended into hell. Following reports of women and children being killed in coal mining accidents at work, commissioners like Scriven headed into mines to see for themselves, and were appalled by what they found.

Quite apart from the children who labored in dangerous conditions, men and women worked side-by-side, stripped to the waist and sweating furiously in the heat. There was “something truly hideous and Satanic about it,” Scriven said—not least because some of the women, if they weren’t completely naked, were wearing trousers.

This, along with their bare breasts, was an affront to Victorian modesty. These young women would be “unsuitable for marriage and unfit to be mothers.” The Labor Tribune, which called itself the “Organ of the Miners,” went further still: “A woman accustomed to such work cannot be expected to know much of household duties or how to make a man’s home comfortable.”

Trousers were shocking. The Manchester Guardian called them “the article of clothing which women ought only to wear in a figure of speech,” the Daily News claimed that the “habitual wearing of the costume tends to destroy all sense of decency,” and even the miners union’ said they were a “most sickening sight.”

But women miners had few options when it came to clothing: flimsier, cooler clothing, which revealed the contours of their body, were seen as “an invitation to promiscuity.” Trousers, and other practical garments, were “unwomanly”—and often led to wardrobe malfunctions. In his 1842 speech to Parliament, Lord Ashley described how the work sometimes wore holes in the crotch of these women and girls’ trousers: “The chain passing high up between the legs of two girls, had worn large holes in their trousers. Any sight more disgustingly indecent or revolting can scarcely be imagined than these girls at work. No brothel can beat it.” (What’s especially striking about these observations is that they seem more concerned about the modesty of the women than that they toiled in life-threatening situations.)

Having women in the mines was financially advantageous to both their bosses and their families. One “underlooker” told the commission that women were paid roughly half of what men were, allowing their employer, the collier, to spend “one shilling to one shilling sixpence more at the alehouse.” Women had worked in Staffordshire mines for centuries, adding crucial coffers to family kitties.

The outcome of this inquiry was swift—the 1842 Miners and Collieries Act forbade all women and girls, and any boy under the age of 10, from working in the mines. They would be replaced by pit ponies, an expensive alternative. Families felt this sudden loss of income acutely. One female miner said, afterwards, that though working underground was not pleasant, it was certainly better than starving. The penalty for employing women in mines was small enough that some women were still illegally employed below-ground—especially as mine-owners often passed this cost onto the women themselves.

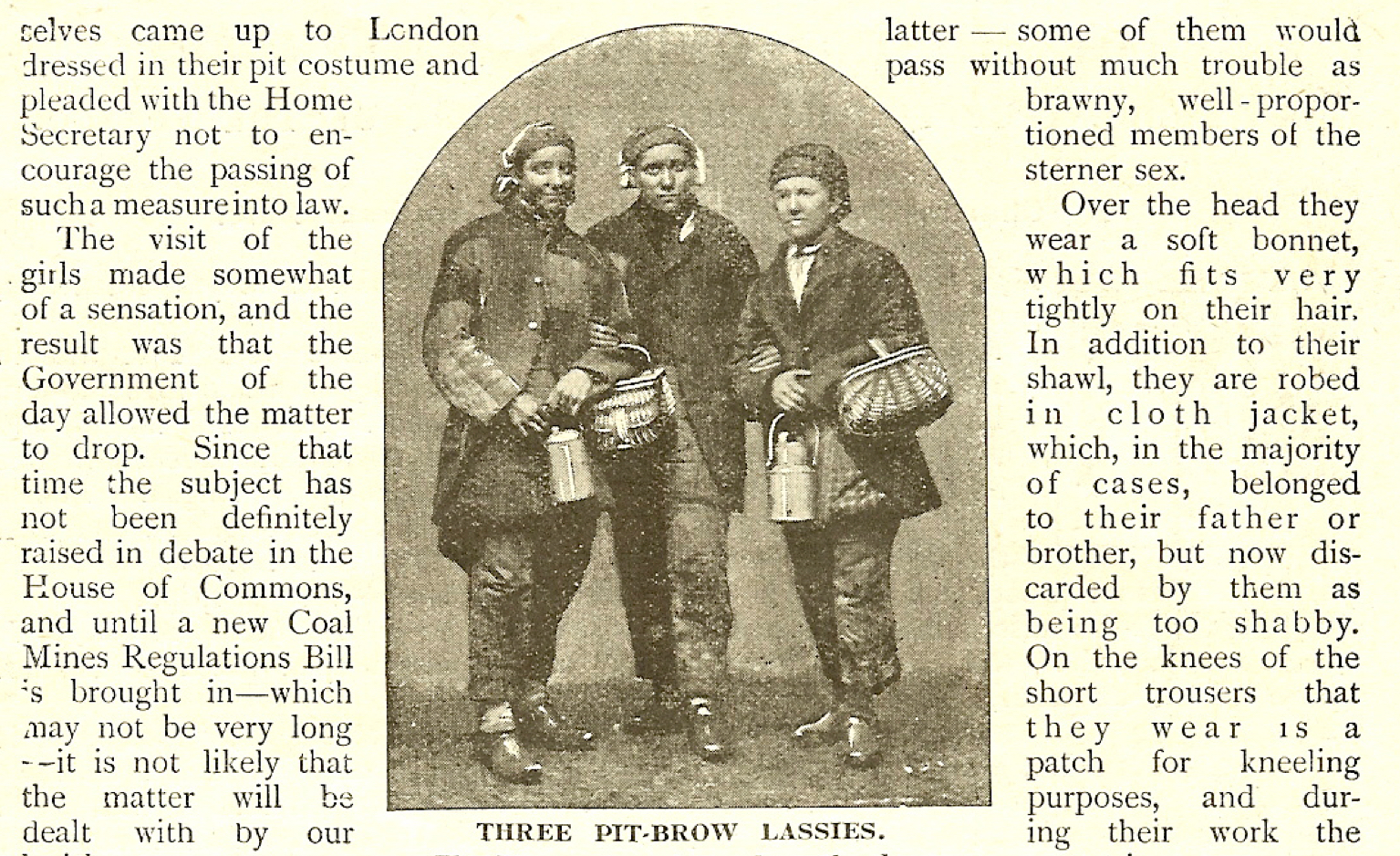

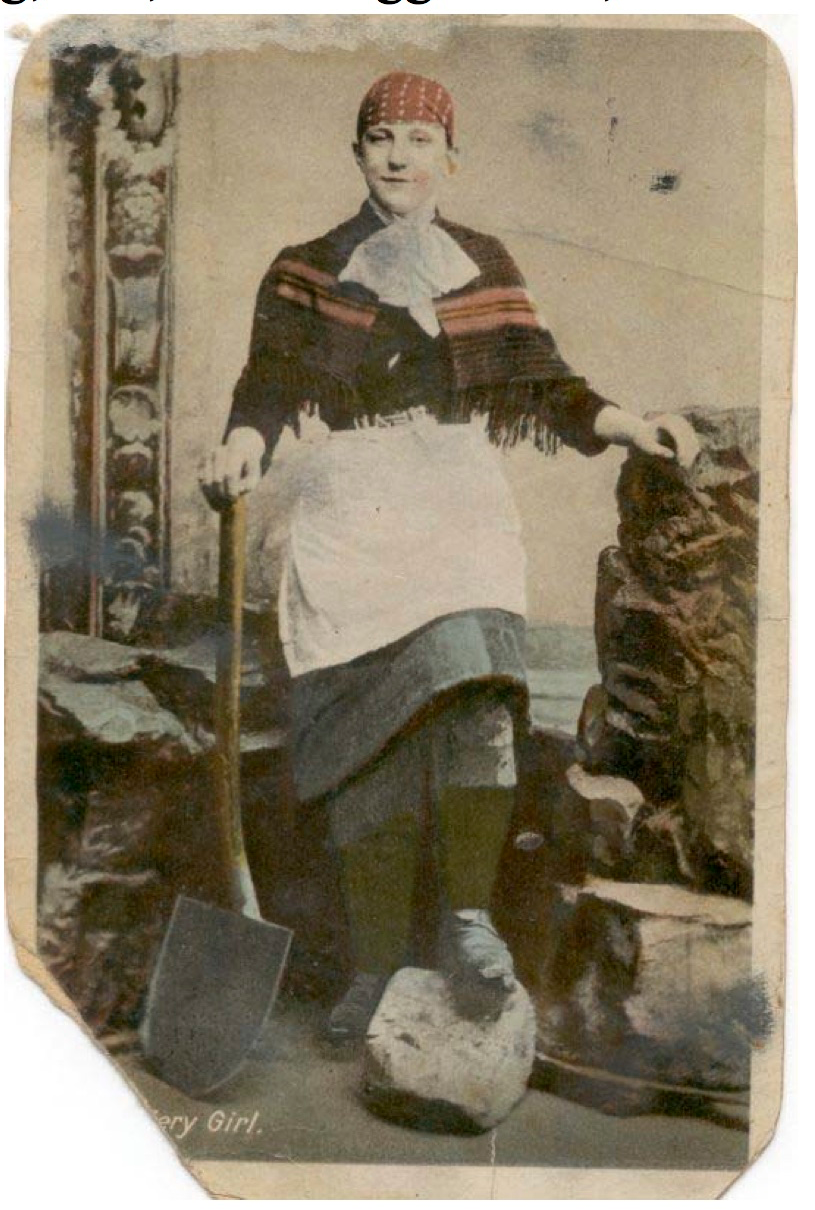

However, by the 1880s, around 11,000 women had found work aboveground at the coalmines, sorting coal. Conditions were cold and dirty, and so they wore a striking ensemble, as described by one onlooker: “She wears a pair of trousers which formerly, were scarcely hidden at all, but are now covered with a skirt reaching just below the knees. Her head is cunningly bandaged with a red handkerchief, which entirely protects the hair from coal dust; across this is a piece of cloth which comes under the chin, with the result that only the face is exposed. A flannel jacket completes the costume.” The women most famous for this outfit were “‘Wigan’s Pit Brow Lasses’.”

These trousers caused some consternation. Below ground, few, if any, non-miners were exposed to this scandalous sight. Now, people feared that the women “dressed and acted like men,” and visitors were restricted from entering the pit to protect their eyes and their moral sensibilities. But people did go, and were somewhere between being titillated and disturbed by what they saw. Frank Hird, a visitor to the mines, described how, at work, “the pit brow lass tucks the skirt around her waist.” When she was on the way to and from home, however, “it is let down, and there is nothing to distinguish her from any ordinary working woman.” But the implication is clear: these “lasses” were different from ordinary working women. Their bifurcated legwear, even under a skirt, showed a degradation of femininity. Wigan pit brow lasses were often characterized as weak and immoral and likely to be drinkers.

Despite restrictions on visitors, people came from far and wide to observe these women in their trousers. Photographers in particular were fond of documenting them in their unusual get-up, and sold their photos later as cartes de visites or postcards. There was a roaring trade in these, which were sometimes blown up to life-size and then hand-colored. Angela V. John in By the Sweat of their Brow: Women Workers at Victorian Coal Mines, writes: “Sometimes the pit girl would be shown dressed for work on one side and wearing her Sunday clothes on the reverse. They were chiefly sold to commercial travellers who bought them as curiosities.” Pit girls seem to have enjoyed being photographed, for which they were sometimes paid a shilling.

Few other mines outside of Wigan had women customarily wearing trousers, and seem proud to have shaken off this moral affront. Scottish women miners were said to “dress like ordinary females, they do not dress like the Wigan ladies,” while the inspector for South Wales described the local women there as “respectably dressed.”

But the pit brow women didn’t seem to be especially unhappy about their costume. (They had other considerations to worry about, like feeding their families on half the wage that the men received.) Many married male miners, and were part of a tightknit local community, sparking the anonymous poem, or perhaps song, “A Pit Brow Wench For Me”:

“I am an Aspull collier, I like a bit of fun

To have a go at football or in the sports to run

So goodbye old companions, adieu to jolity,

For I have found a sweetheart, and she’s all the world to me.Could you but see my Nancy, among the tubs of coal,

In tucked up skirt and breeches, she looks exceedingly droll,

Her face besmear’d with coal dust, as black as black can be,

She is a pit brow lassie but she’s all the world to me.”

Many pit brow lasses were very much in favor of being allowed to work in and around coal mines—not just for the money, but because they enjoyed the fresh air. The other option, working in a factory, was stuffy and unsanitary, with workplace accidents almost as common. And, even while spectators may have thought of them as unladylike, they did what they could to assert their femininity in the pit among the dirt and the dust. A French visitor described their “taste for feminine things and a love of ribbons. Most of them, in fact, wear around their neck ties, whose folds will soon become nothing more than little nests of coal dust.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook