The Sweet Monopoly That Enriched the Mormon Church

A divine revelation led to the sugar beet business.

“Picture with me, if you will, a farmer driving a large open-bed truck filled with sugar beets en route to the sugar refinery.”

So begins a message from Thomas Monson, the then-president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (LDS), in 2009.

“As the farmer drives along a bumpy dirt road, some of the sugar beets bounce from the truck and are strewn along the roadside. When he realizes he’s lost some beets, he [tells] his helpers, ‘There’s just as much sugar in those which have slipped off. Let’s go back and get them.’”

In this story, titled Sugar Beets and the Worth of a Soul, Monson explains that the sugar beets represent members of the LDS Church, and the fallen ones are the men, women, and children who have strayed from their Mormon path.

Clearly, members of the LDS church are sweet on beets. In fact, Mormons embedded beet sugar so deeply into Utah history and culture that some schools still use Beetdiggers as their mascot.

But to understand the church’s relationship with sugar, you need to go back to the late 1800s, when then-LDS president Wilford Woodruff told a group of followers that he received a message from God instructing him to create a sugar company. Mormons would not only create and control that company, garnering huge profits for the Church and Utah. They would also create a corporation that monopolized the sugar industry of the western United States well into the 20th century.

“The inspiration of the Lord to me is building this factory,” pronounced Woodruff in 1890. “Every time I think of abandoning it, there is darkness; and every time I think of building it, there is light.”

If his followers or fellow LDS leaders were dubious about this proclamation, few could have blamed them. Mormons, including former LDS presidents Brigham Young and John Taylor, tried to harvest sugar beets decades before Woodruff’s presidency. All three were highly motivated to make to make the Church and its followers more self-sufficient.

LDS members had faced years of scrutiny and ostracization due to their religious teachings and polygamist practices. Communities of Mormons were driven out of midwestern territories in the 1840s by angry mobs. They relocated to Utah, a territory that was mostly unsettled at the time.

Mormons considered themselves outsiders. Constant migration meant they had to build new homesteads and industries wherever they landed. In sugar beets, they saw a means to support an independent community. Sugar was still an expensive commodity—three pounds in the 1830s could sell for two dollars, the equivalent to around $50 dollars in 2016—which they hoped to sell profitably rather than rely on imports from the eastern United States. Plentiful sugar would also help Mormons preserve foods between harvests.

But Young and Taylor had no luck with their harvest. Their beet seeds didn’t take well to Utah soil, and Mormons didn’t know how to chemically process the crops for their sucrose. Many followers who had invested suffered financial losses, and Mormon leadership abandoned their efforts.

Thirty years later, though, English horticulturist Arthur Stayner helped re-ignite Mormons’ hopes for successful sugar production. In the late 1880s, he figured out how to mass produce sugar from beets, and received $5,000 from the Utah government for producing the first 7,000 pounds of processed sugar in the territory. But he needed additional funding, and a facility. Because of the Mormons’ history with sugar and their local influence, he turned to Woodruff and the LDS church for capital.

Woodruff initially said no, due to the church’s financial condition and a negative report from the church-operated Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institute, which advised against investments in sugar.

“The change of heart,” writes Matthew Godfrey in Religion, Politics and Sugar, “came after Woodruff obtained a revelation from God telling him to establish the beet sugar industry in Utah.”

Church leadership, however, was more uncertain about the sugar business. To convince them, Woodruff sent out an informational circular. He promised that through successful sugar production, Mormons would no longer be at the mercy of outside interference or imported sugar. They would be independent. They would have work.

With the additional prospect of a one-cent-per-pound incentive from the state government, and two-cents-per-pound from the federal government, LDS leaders added their moral and financial support.

The church-owned Utah Sugar Company officially incorporated in 1889.

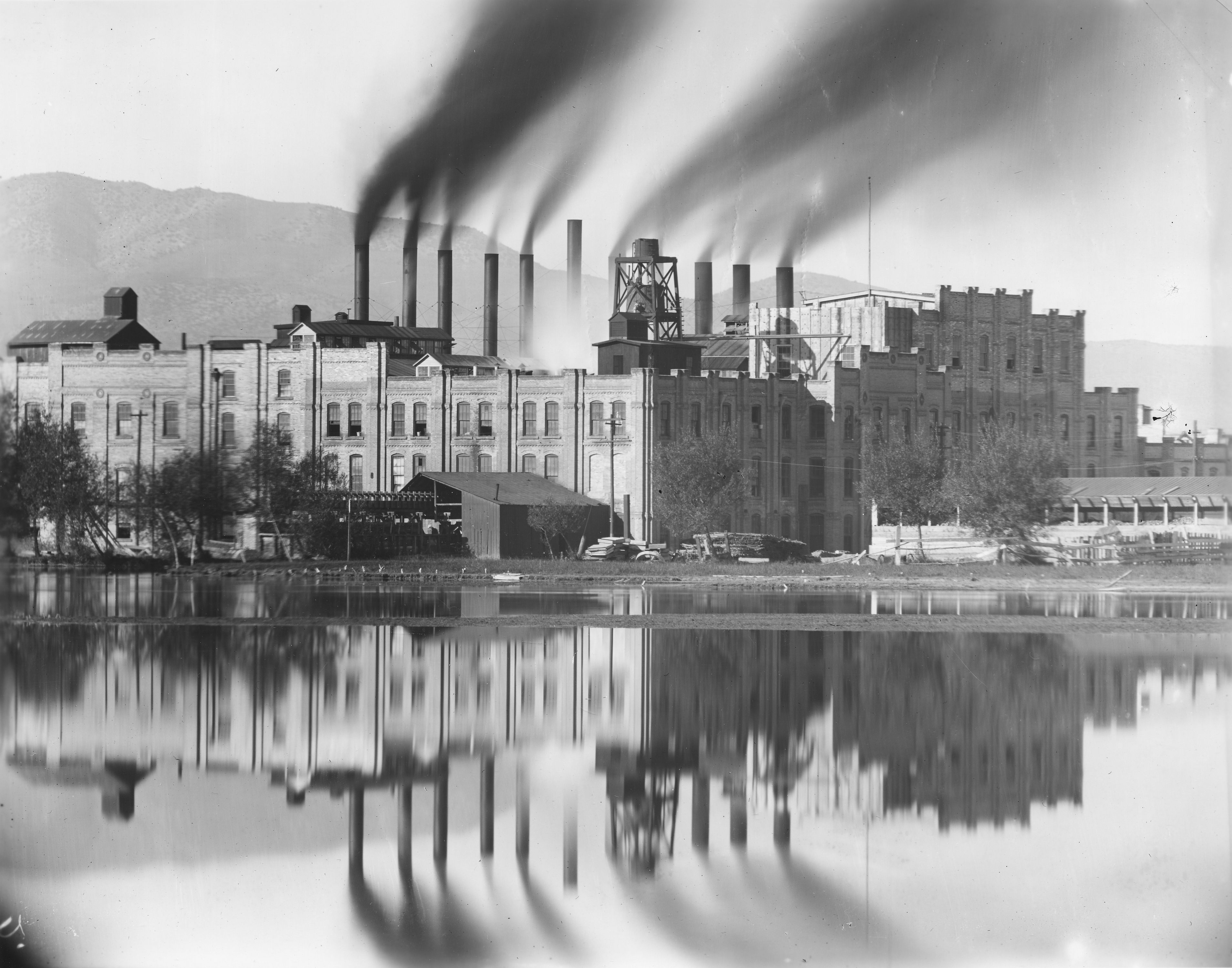

To help raise capital for a first factory, Woodruff sent missionaries to secure financial backing from prominent Utah businesses. He suggested to potential donors that monetary contributions to the sugar company were part of one’s “ecclesiastical responsibility.” Through these fundraising efforts, Woodruff and church leadership raised the funds to construct a first sugar processing plant in Lehi, Utah.

Mormons’ reactions reflected their high hopes. The church-owned Deseret News reported in 1891 that crowds of citizens came to the newly-opened factory to watch sugar being processed. They filled the factory floor and made it hard for workers to move around.

“When [the first] clear white sugar was passed out directly into the hands of the fascinated onlookers,” the paper reported, “there were shouts of ‘Hurrah!’ and ‘Hosanna!’ Utah was in the sugar business.”

The Lehi Factory produced 20,000 pounds of sugar that day, and sent it via the Union Pacific Railroad into Salt Lake City.

“Within days of the arrival of the first sweet sacks in Salt Lake City,” the Deseret News reported, “local confectioners were advertising ‘The first candy made of Utah sugar.’”

Utah was a labor-rich territory at this time. A high birth rate, underemployment, and limited labor laws meant plenty of men and boys could tend to the beets that were sent to the factory for processing. The state also irrigated farmland, enabling farmers to make use of new, more advanced farming practices. Labor-intensive beet farming provided sugar and jobs for Utah’s people, feed to its livestock, conditioner and enrichment for its arid soil, and high cash returns for investors—all of whom were LDS leaders—and farmers.

After several years of profitable production, the actions of Church leaders appeared less like the Hail Mary of a religious group trying to survive and more like classic corporate strategy. In 1902, to grow the business and provide a quicker return for investors, the Church sold its controlling interest in Utah Sugar to the American Sugar Refining Company, a sugar trust that held a near-monopoly on eastern sugar production. (The Church would buy back its share in 1914.) The extra cash enabled Utah Sugar to expand into Idaho, where they opened more factories and established more companies: the Idaho Sugar Company and Western Idaho. Both companies had the same LDS directors, upper management, and leadership.

“Apparently, God, in his determination to see the sugar beet industry succeed,” writes Matthew Godfrey, “wanted his spiritual leaders to oversee the business.”

By 1907, sugar companies in Utah and Idaho conglomerated into the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company (U and I), estimated at the time to be worth $13 million. (That’s over $300 million in 2018 dollars.) Agriculture was a leading industry in Utah, and Utah-Idaho Sugar helped make sugar beets its top commodity. High profits brought newfound financial stability and political influence to both Church members and LDS leaders. What was once a wandering tribe was now headed by highly regarded millionaire executives. Sugar beet profits helped pave the way to the Church’s current wealth and contemporary Mormons’ status as a relatively well-off demographic.

But the success of Utah-Idaho Sugar, and the church’s role in that success, also attracted national scrutiny.

In 1911, in light of frustrations that the American Sugar Refining Company had yet to be prosecuted for former violations of the Antitrust Act, a special House committee led by Democrat Thomas Hardwick began investigating the relationship between American Sugar and the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company. Hardwick alleged that American Sugar’s ownership in beet sugar factories, including U and I, was a further attempt to monopolize the sugar industry. What once liberated Utah farmers and LDS members from federal interference now, Hardwick believed, meant higher prices for consumers and lower wages paid to farmers for beets and sugar cane.

The committee eventually found the relationship between the two corporations inappropriate due to price gouging, defrauding consumers, stock watering, and a breach of the Sherman Antitrust Act. But officials took no action to break up their alleged monopoly. Most of the illegalities, according to Godfrey in Religion, Politics and Sugar, occurred under the leadership of American Sugar’s Henry Havemeyer, who at that point had been dead for seven years.

In 1922, the case over those former misdeeds by American Sugar was dropped after the company’s admission to previous Sherman Act violations. By this time, they no longer had any holdings with U and I, so the government didn’t feel it necessary to dissolve Utah-Idaho.

In 1923, the Federal Trade Commission found Utah-Idaho guilty of unfair competition, monopolizing the sugar industry in the region, and failing to comply with government-imposed price controls. But the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the ruling in 1927.

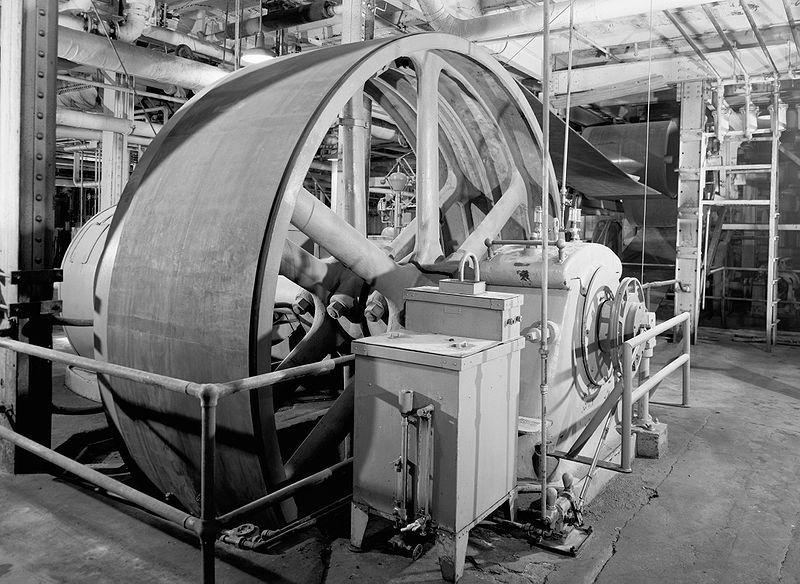

For decades, the company survived hostile government regulators, the Great Depression, a World War, and a blight caused by the white fly that decimated much of the beet crop. But by the mid-twentieth century, these challenges resulted in shuttered sugar factories throughout the western United States. Sugar companies like Utah-Idaho ultimately fell victim to the mechanization and industrialization of cane sugar, which was cheaper and easier to produce.

The Mormon Church continued to have a financial interest in the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company well into the 1980s, when it finally sold its share. But for almost 100 years, the Latter-Day Saints created a thriving agricultural-based economy in the intermountain west. They changed Utah’s economy, brought a viable, though legally questionable, business to the Mormon people, and created a large, highly profitable company.

And you have to admit, that’s a pretty sweet deal.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook