The Beautiful, Forgotten and Moving Graves of New England’s Slaves

This photo project reveals the powerful history tucked into Rhode Island’s cemeteries.

Most of New England’s colonial-era graveyards hold the bones of slaves. This is true not only of the urban graveyards of Boston and Newport, but also of the sleepy little cemeteries nestled among the clapboard churches and old stone walls in rural villages from Norwich, Connecticut to Jaffrey Center, New Hampshire. Unlike the African Burial Ground in New York City, which was formed after black bodies were banned from Trinity Churchyard in 1697, most New England municipalities maintained unified burying places that segregated black and white graves within a shared boundary.

So where to find these forgotten bits of history? The vast majority of slaves’ graves are unmarked, but a few have archetypical New England gravestones. In Cambridge, Massachusetts, two diminutive markers stand less than 100 yards from Harvard Yard, commemorating the short lives of Harvard-affiliated slaves: 15-year-old Cicely (d. 1714), who was owned by the Reverend William Brattle, a longtime Fellow of Harvard’s Corporation; and 22-year-old Jane (d. 1741), who worked alongside her mother, siblings, and half a dozen other slaves at the command of Andrew Bordman, the Harvard College steward.

Many more graves may have had ephemeral markers—uncarved stones, wooden slats, glass bottles, or other tokens—but enduring gravestones for New England slaves are rare. More than 6,000 black Bostonians were buried in the city’s historic graveyards in the century before the American Revolution, accounting for one in every six burials.

Photographing these sites has been a passion of mine for years. Below, here is a selection of images that focus specifically on the ways in which public memorials in Rhode Island represented black families in the century and a half before the Civil War.

Pompe Stevens was a slave and a stone carver. Based on the style of the gravestones he signed, he was probably enslaved and trained by William Stevens, a member of the famous Stevens stonecarving family. The fraternal relationship between Pompe Stevens and Cuffe Gibbs is not mentioned in any paper document. As far as the law and the historical record were concerned, enslavement broke any familial ties between them. Pompe Stevens did not accept this erasure.

When Cuffe died in 1768, Pompe carved this gravestone as a memorial to his brother, to their family, and to his own skill.

This memorial, for siblings Lonnon and Hagar, rests in a pile of broken gravestones behind the John Stevens stonecarving shop on Thames Street in Newport. This photo was taken in 2009. Since that time, some of these stones (“Lucy wife of Cato Ayrault”) have been restored to the Newport Common Burying Ground. Lonnon and Hagar’s stone has not.

Even when slaves were able to marry, they were not allowed to form legal families. Gravestones like this one illustrate that tension by memorializing wives and husbands who bore the surnames of different enslavers. The right to take a husband’s last name, rather than a slaveowner’s, was a mark of freedom. For enslaved women, the inability to take a husband’s name marked the fundamental vulnerability of their families.

The gravestone that Pompe Stevens carved for his brother, Cuffe Gibbs, is part of a larger memorial to their extended family.

Cuffe is buried beside “Princ, Son of Pompe Stevens & Silva Gould,” his infant nephew. On his other side lies Primus Gibbs (d. 1775), a man of about Cuffe’s own age, probably enslaved by the same family. Perhaps they were brothers as well, either by blood or bondage. Further down the row are Susey Howard, “daughter of Primus Gibbs” (d. 1770) and Jem Howard, “Twin brother of Quam and son of Phillis” (d. 1771).

This is not a plot controlled by a single slaveowner. At least four white households are implied (Gould, Stevens, Gibbs, Howard), but not explicitly acknowledged. All of the named relationships in the plot (son, brother, daughter, twin) are between black men, women, and children. None of the five stones calls anyone a “servant.” It is a family plot.

In the 1750s, Pompey Scott and Violet Robinson buried at least three young children: Pompe, Mary, and Pegge. Their graves are clustered together, each gravestone testifying to the bond between parents and children. Still, the different surnames underscored the fact that enslaved Newporters could not form autonomous households. In 1779, during the British occupation of Newport, Pompey and Violet lost their teenage daughter, Susannah.

They buried her near her siblings under a gravestone that marked an important shift by naming her the “daughter of Pompy and Violet Scott.” Perhaps the Scotts, like so many other black Newporters found a greater degree of freedom in British-occupied territories than they had under American rule.

The nested dependency of enslaved women is encapsulated in this epitaph. Dinah, herself a slave, defined in relation to her husband, himself a slave.

Time, weather, and lawnmowers chip away at 18th-century gravestones in Newport.

These four young children are buried in a group. Were Jack and Sango the same man? Many black Newporters went by more than one name. It is possible that all four children had the same father (Sango/Jack), with Hager’s son born after Cuffe and Tom, but before Nancy. It is also possible that the children’s parents were three different couples (Jack & Violet, Sango & Violet, Jack & Hager). Whatever the configuration of this family group, their burials suggest family ties. The children are buried together, as siblings often were.

This gravestone is badly weathered, with a large hole and substantial chips. It will probably not last through many more winters.

In 1790, the musician Newport Gardner (also known as Occramar Marycoo) commissioned John Stevens III to carve a gravestone for his baby daughter, Silva. Stevens charged Gardner 15 shillings for “cutting a pair of Grave Stones for your Child Silva,” a debt that Gardner paid with 10 bushels of potatoes.

Gardner, who had been born free in West Africa, paid his own ransom the next year. Over the next several decades, he was a pillar of civic life in Newport, becoming a music teacher, schoolmaster, deacon, and published composer. In 1826, he led a group of African-born Rhode Islanders and their families back to Liberia. One witness to the departure quoted Gardner’s farewell: “I go to set an example to the youth of my race. I go to encourage the young. They can never be elevated here. I have tried it sixty years — it is in vain. Could I by my example lead them to set sail, and I die the next day, I should be satisfied.”

Slaveowners defined slaves as dependents. They erased family ties between slaves, but insisted that a familial bond existed between slaves and the people who enslaved them. Gravestones from the 18th century often identify slaves as the “servant of” a white slaveowner in much the same way the gravestones of dependent Euro-Americans defined them as the “wife of” her husband or the “son of” his parents. Cato’s epitaph goes a step further, telling his life story as a series of enslavements to different masters.

“Servant” was the preferred euphemism in 18th century New England. A two-year-old is not a “servant.”

Mille and Katharine were teenagers when they died. Were they sisters? Did they have parents nearby? Or did they survive the Middle Passage as young girls, only to die in Newport?

This gravestone explicitly defines Mille and Katharine in terms of their relationship with their enslaver, Henry Bull. It is a double stone, a style that white Newporters usually reserved for married couples or young siblings. The form is a reminder of the forced intimacy that slavery thrust upon the enslaved. There is no way to know whether Mille and Katherine loved one another, hated one another, or even whether they lived in the Bull household at the same time (Katharine may have been enslaved after Mille’s death). Yet, in memorializing them together, side by side, this stone also raises the possibility of mutual support and camaraderie.

Pero was one of the slaves who built University Hall at Brown University. A 2008 essay by Brown University Curator Robert P. Emlen argues that the language of Pero’s gravestone “emphasizes Pero’s subservience while it aggrandizes Henry Paget,” but that the Genny’s and Sylvia’s gravestones emphasize relationships among the family members and deploy surnames and the term “wife” to lend dignity to extra-legal familial ties.

The mismatch of surnames on Genny’s gravestone also calls attention to the precariousness of her status as Pero’s “wife.” Her legal status as a slave always trumped her marriage. Providence residents may recognize the surname Waterman — Waterman Street is one of the main roads bounding the college green at Brown University.

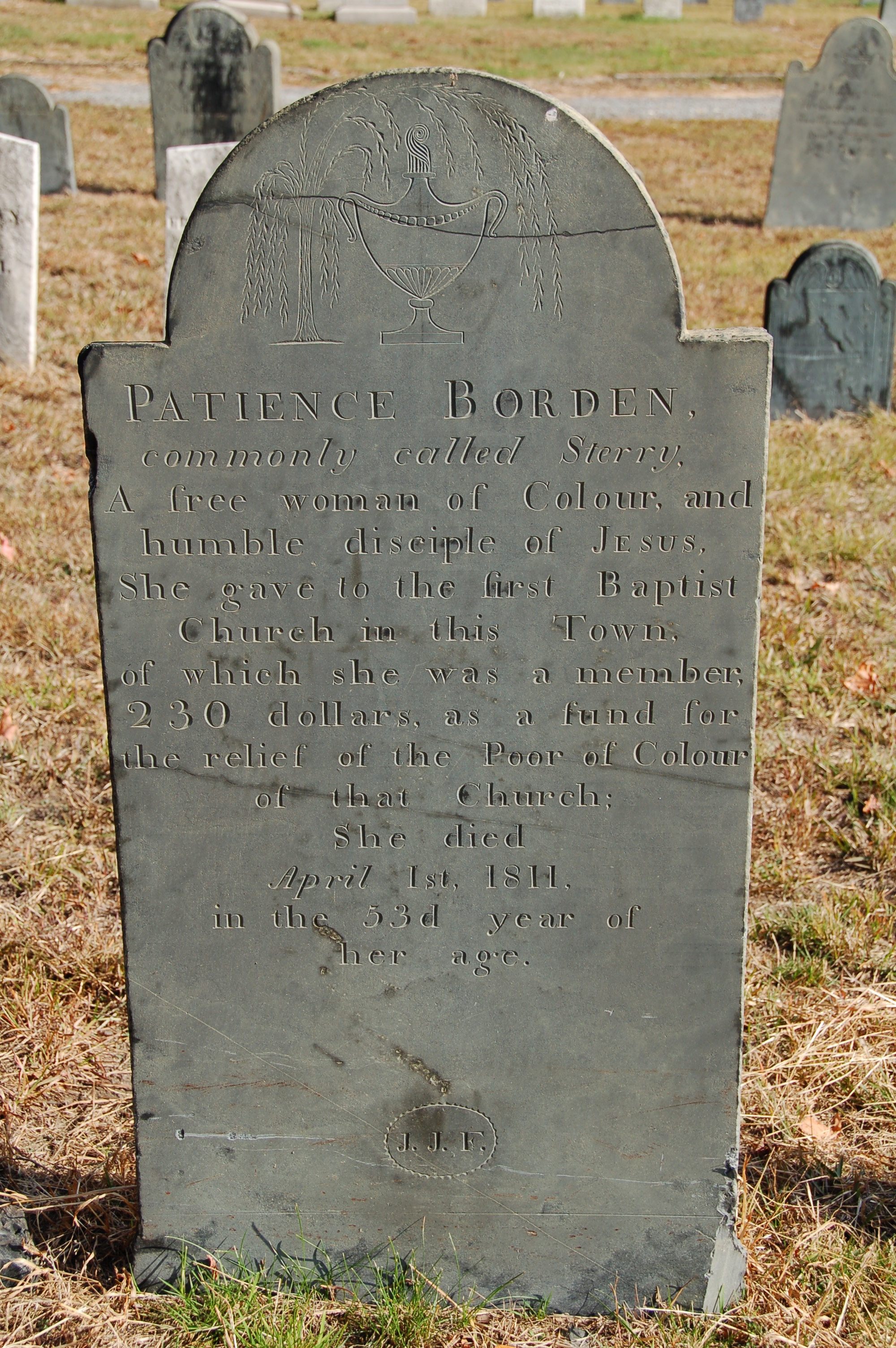

Gravestones are public monuments. In an era when black Rhode Islanders were gaining access to the public sphere, they created enduring memorials to their spiritual, financial, and philanthropic achievements.

In 1784, Rhode Island passed a gradual emancipation law. All slaves born before that year would remain slaves for life; children born to enslaved mothers would be emancipated at age 21. While some Rhode Islanders remained enslaved until the state abolished slavery in 1842, a patchwork of self-purchasing, private manumission, and escape efforts transformed the diasporic community in the decades after the American Revolution. Before the war, most black Rhode Islanders were enslaved; after the war, most were free.

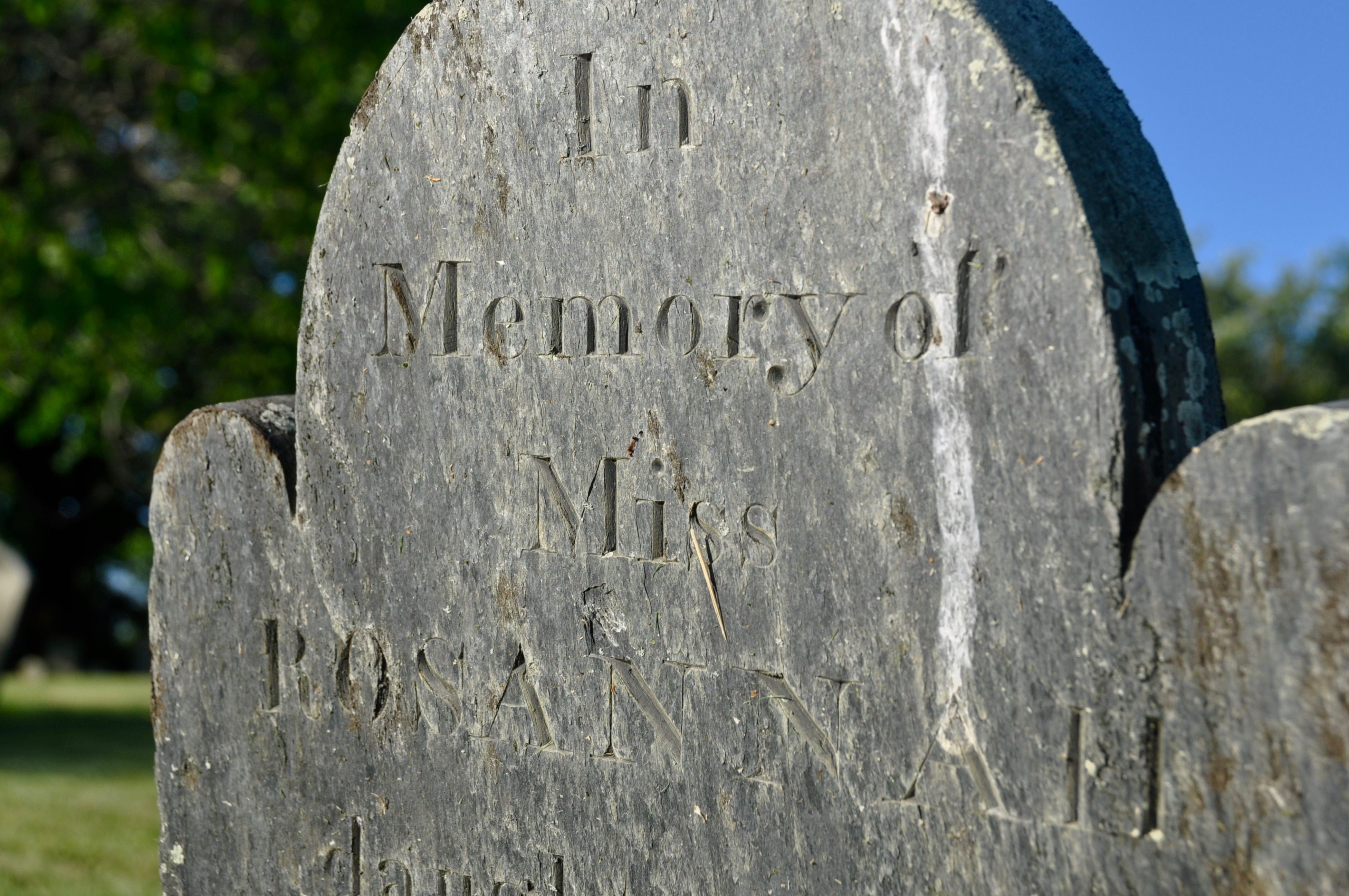

Rosannah Hicks’s gravestone demonstrates how much had changed for free families by 1817. Not only do Rosannah’s parents, Cudgo and Freelove Hicks, share a surname, they claim the honorific “Miss” for their beloved daughter.

Gravestones are memorials for the dead. They are also public declarations made by the living. For black Rhode Islanders living during the transition from slavery to freedom, funerals and memorials were a way of demonstrating familial love and financial independence. Like the epitaph that Pompe Stevens carved for Cuffe Gibbs, Ceesar Wheaton’s epitaph is an explicit testament to both affection and self-determination

A 1790 letter from Newport’s Free African Union Society to its members regarding conduct at funerals demonstrates the Society’s belief that “sober” funerals would win the approbation of white Newporters. These hopes were never realized. It read:

“We also particularly recommend to all and every Member that shall find freedom, That they dress themselves and appear decent on all occasions, that so they may be useful to all and every such burying, as above, and within described, that all the Spectators may not have it in their Power to cast such Game contempt, as in times past.

And above all things, Dearly Beloved, That ye be sober, be vigilant because your adversary, the Devil, is a roaring lion walking about seeking whom he may devour.

And no, brethren, we exhort you to warn them that are unruly, comfort the feeble-minded, support the weak, be patient toward all men. May God Almighty bless the works of our hands, and prosper us untill time shall be no longer.”

This cluster of gravestones shows how family ties endured over an entire century.

The first burial in this plot is Prince, a “Servant of Jn Stevens” who died in 1749. John Stevens, a stonemason and carver of gravestones, enslaved several people (his account books mention that he also hired black Newporters for short-term jobs like building chimneys and laying foundations).

The other five stones in this group commemorate relatives of Zingo Stevens, who was emancipated in John Stevens’s 1774 will (after 7 years of service to Stevens’s widow).

The first of these is a portrait stone for Zingo’s wife, Phillis, and their son, Prince. Prince was a common name among black Newporters, but it is possible that the may have been named for the earlier Prince. Was the older Prince Zingo’s father? A mentor? A brother in bondage under the same roof? Note the language of this epitaph—Phillis was the “late faithful Servant of Josias Lyndon Esq. and Wife of Zingo Stevens.” Under the logic of this memorial, Phillis’s most important relationship was with her enslaver; her marriage was secondary. (This stone was carved by John Stevens III, the son of Zingo’s enslaver).

Zingo’s second wife, Elizabeth, and their stillborn daughter (d. 1779) are buried nearby. His third wife, Violet (d. 1803) is also there. The final stones are for Zingo’s daughter, Elizabeth (if her age is given correctly on the stone, she was Phillis’s daughter, born c. 1768), and her husband, Cuffe Rodman. Cuffe died in 1809, but Sarah survived until January 23, 1863. She died at age 94, three weeks after the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect.

The gravestones of Charles Haskell and Lucy Haskell are monuments to the couple’s prosperity and achievements. Lucy’s epitaph also invokes an understanding of salvation as the erasure of racial distinction, in which spiritual equality is imagined as a state of whiteness.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook