The Miseducation of John Muir

A close examination of the wilderness icon’s early travels reveal a deep love for trees, and some ugly feelings about people.

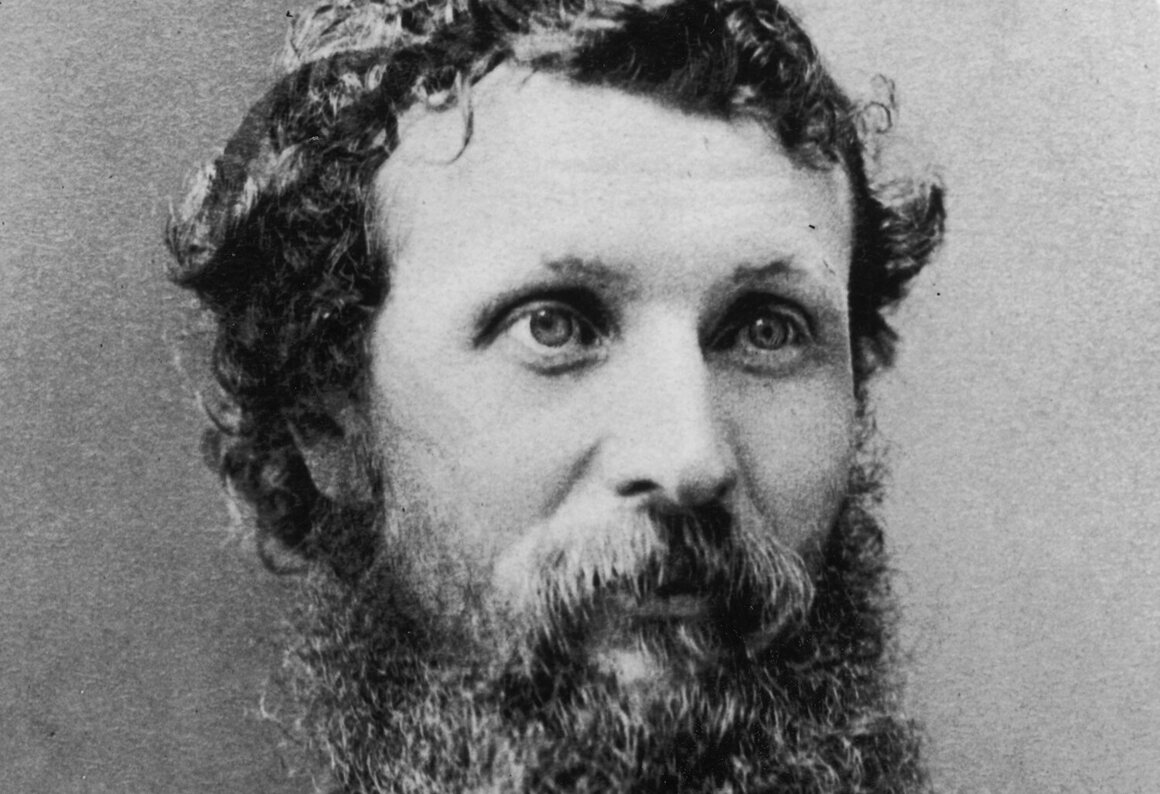

John Muir, c. 1875. (Photo: Fotosearch/Stringer/Getty Images)

It’s quite possible that America’s future was changed on the evening of March 6, 1867, in a factory that manufactured carriage parts in the booming railroad city of Indianapolis.

The large workroom, typically smoky and bustling with workers, was near empty. Factory manager John Muir’s task was simple: The machine’s drive belts, which looped around the vast room like the unspooled guts of a primordial beast, needed to be retightened so the following morning they’d run more efficiently. Muir had already made a name for himself as an impressive backwoods inventor. His “early rising machine” was an intricate alarm clock that tipped the sleeper onto the floor. His “wood kindling starting machine” used an alarm clock to trigger the release of a drop sulfuric acid onto a spoonful of chemicals, generating a flame, igniting the kindling. For the carriage factory, this unique mind was a boon. Muir had already improved wheel design and cut fuel costs.

In the darkening workroom he grasped a file and ground it between the tightly woven threads of the leather belt. The file slipped, sprang up pointy end first, and sank deep into the white of Muir’s right eye. Out dripped about a third of a teaspoon of ocular fluid. “My right eye is gone!” he howled back at his boarding house, “closed forever on God’s beauty.” In fact, thanks to a mysterious immune response known as sympathetic blindness, his left eye was gone too. The promising young machinist was blind.

Yosemite National Park. (Photo: Esther Lee/CC BY 2.0)

Now, of course, we remember John Muir quite differently. If you can measure America’s regard for someone by how many things get named in their honor, John Muir may be one of the country’s greatest heroes. He has at least one high school, 21 elementary schools, six middle schools and one college named after him, as well as a glacier, a mountain, a woods, a cabin, an inlet, a highway, a library, a motel, a medical center, a tea room and a minor planet.

He has been called “The Father of our National Parks”, a “Wilderness Prophet,” and if you visit a National Park this summer you may indeed have Muir to thank. His writing and activism are credited with inspiring Yosemite, Grand Canyon and Mount Rainier, among other parks. This August, the National Park Service celebrates its centennial—Yellowstone was established by Congress in 1872, but it wasn’t until August 25, 1916, that President Woodrow Wilson, in an effort to put America’s sprawling park system under one department, signed an act creating the National Park Service. Galas are planned and Muir is featured prominently—his visage will be cast into gold, on a $5 coin alongside President Teddy Roosevelt.

His brand, as they say, is strong. But do we really know this man? Over the past few years, Americans have confronted the country’s past with vigor, removing problematic early leaders and symbols like Confederate flags from monuments and money and street signs. College and government institutions are regularly fielding calls to remove more. It might be time to reassess Muir’s legacy, as we tend to see only the pictures of the explorer in later life, greeting presidents amid the jaw-dropping splendor of America’s West. Largely absent from the official record is his early journey through Appalachia and the Deep South, one that helped shape his future adventures and worldview. A close reading reveals some ugly truths about the paternity of American park systems.

Dunbar, Scotland. Muir was born in the house on the left; later, his father bought the bigger building on the right to be the family home. (Photo: Public Domain)

Muir was born in Dunbar, Scotland, the third child of a zealot Christian father and a mother who enjoyed flowers, poetry, and walking alone in the countryside—her husband eventually forbid this unchaste activity. Muir’s childhood was strikingly brutal for a contemplative future tree-hugger. He built a homemade gun and fired it at seagulls, he asked the town butcher for a pig’s bladder and then played football with it, and he was a prolific schoolyard fighter. Then, in 1849, at the age of 11, he moved to America.

Upon settling with his family in rural Wisconsin, young Muir was immediately put to work, preparing the land for farming. Days were often 16 to 17 hours long; grinding scythes, tending cattle, harvesting corn, potatoes and wheat. Single-handedly digging a 90-foot well through solid sandstone with nothing but a mason’s chisel, 18-year-old Muir nearly died of choke-damp—a condition common in mines, when oxygen levels drop too low for sustaining human life. Still, there was time on the occasional holiday, and a few hours on Sunday, for romping through the woods to gorge on dewberries, hickory nuts and wild apples, or riding his horse Nob, who he fed live field mice, or hunting deer, muskrats, Canadian geese and even a loon. “The bonnie things, but they were made to be killed,” his father told him, “and sent for us to eat as the quails were sent to God’s chosen people, the Israelites, when they were starving in the desert ayont the Red Sea.”

Later, as his new homeland was being torn apart by civil war, young Muir escaped his tyrannical father and slipped into the woods. Near Niagara Falls he fended off a pack of wolves, and in the frozen swamps of Ontario, according to letters written to friends and family, he discovered an orchid so beautiful he cried. But by 1866 he had settled back down, earning his job at the Indianapolis carriage parts factory.

Just months before the accident, Muir had enthusiastically written to his brother Daniel: “I really have some talent for invention, and I just think that I will turn all my attention that way at once.” But blighted and bedridden, Muir realized he was on the wrong life track. It was not the machines he missed most, but his beloved plants. A month later, his vision miraculously returned. Muir was like a man resurrected. “I have risen from the grave,” he wrote in a letter.

Muir, pictured later in life, seated on a rock. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-52000)

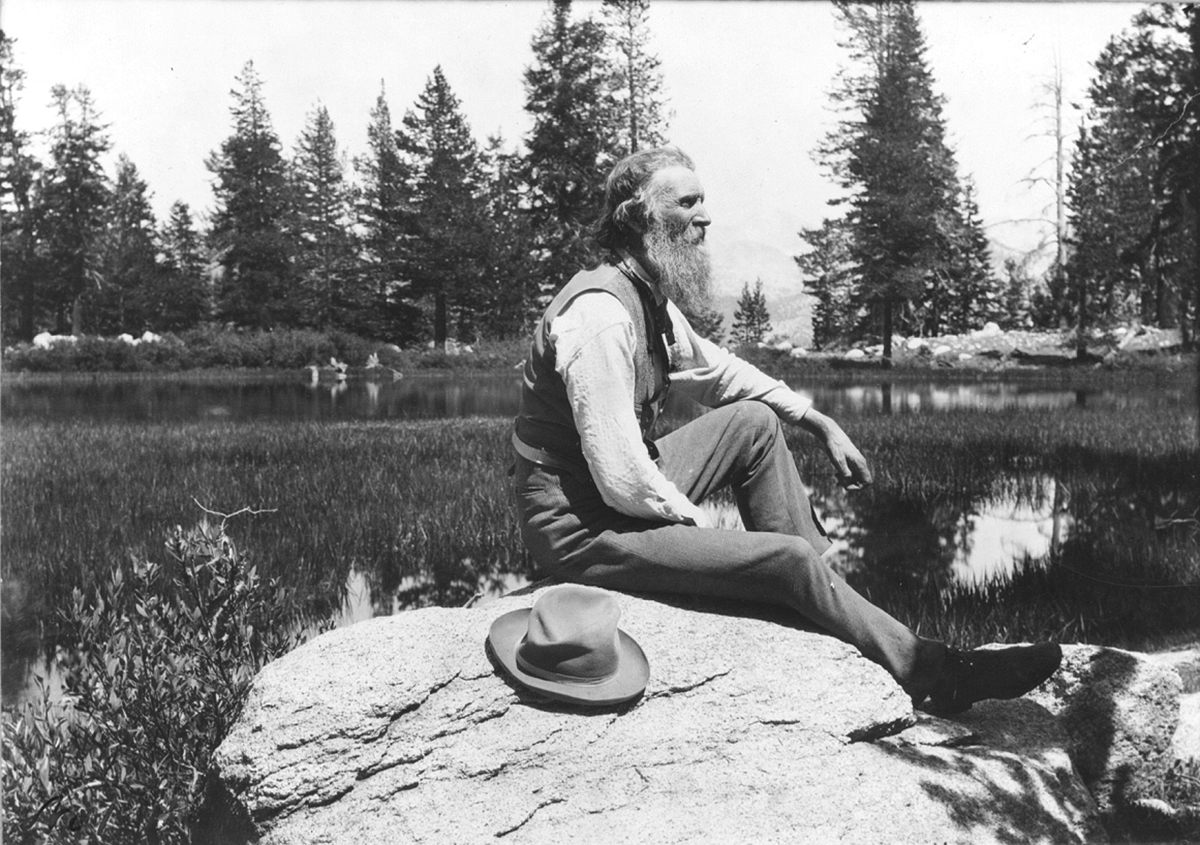

Goodbye now to the world of machines, he would follow his plant heart after all. Inspired by 18th century adventurers like Mungo Park, who journeyed deep into Africa, and Alexander von Humboldt, who trekked across South America, Muir burned for a botanical adventure. Although he wanted to see the Amazon, his first trip would be the American South. He packed books and a plant press into a rucksack and on September 1, 1867, at the age of 29, starting at the Indiana/Kentucky border, Muir embarked on a 1,000 mile walk to the Gulf of Mexico. At the time, it was a bit like walking across Iraq. Some 250,000 Southern men had been killed in the Civil War, certain Tennessee towns lost nearly an entire male generation, and much of Appalachia remained thick with bandits. Yet Muir, with twinkling eyes, a scratchy beard and just one change of underwear, lit a course straight through the territory.

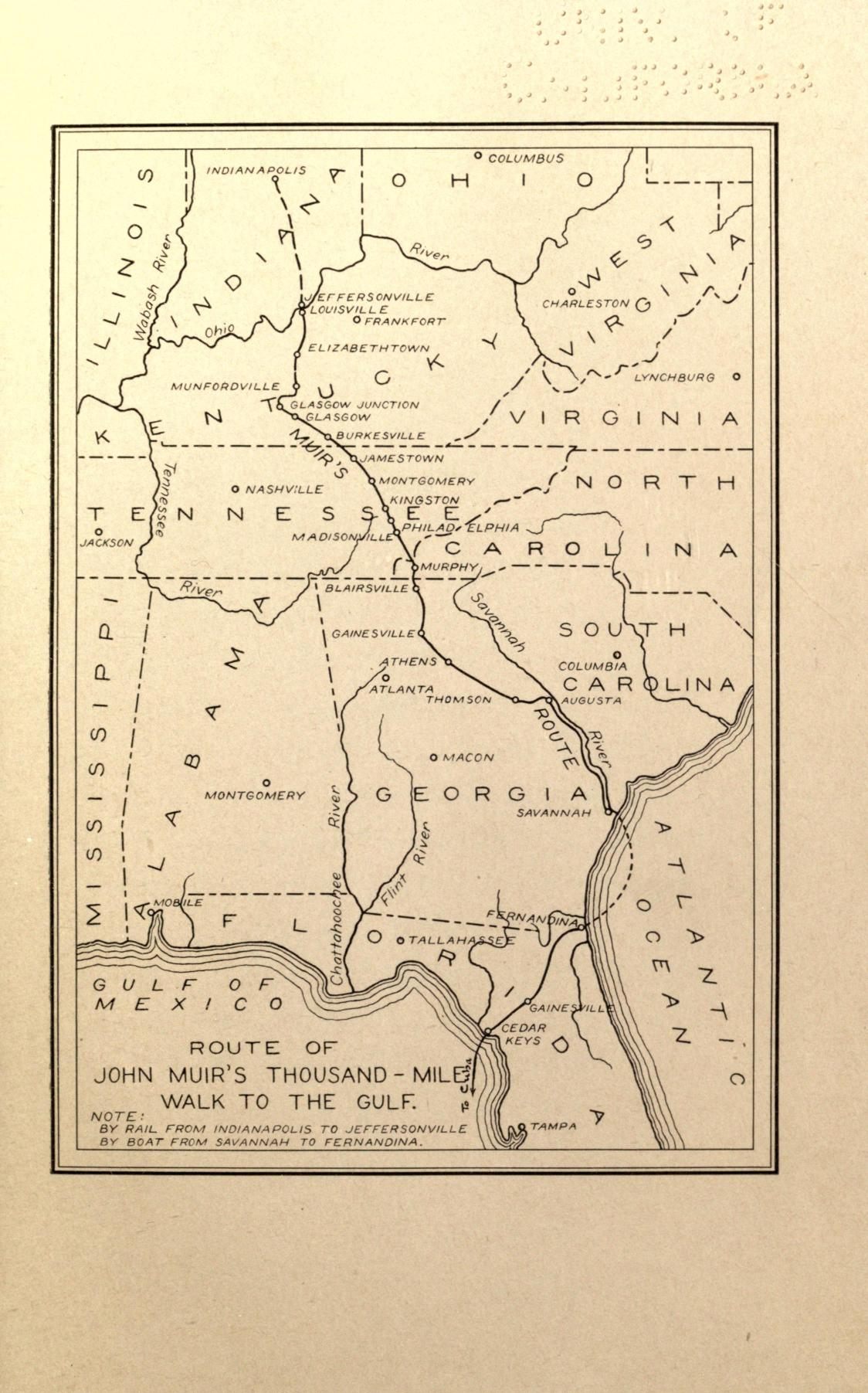

It is here, in Tennessee, where Muir, who went on to become a respected mountaineer, climbed “the first real mountains that my foot ever touched or eyes beheld.” Further along, in Georgia, while camped in Savanna’s Spanish-moss draped Bonaventure Cemetery, Muir realized death was not the hellfire his father claimed it to be, but “stingless indeed, and as beautiful as life.” And in the swamps of Florida, Muir spied his first palmetto, and wondered whether or not plants had souls. You can see it forming, Muir’s aesthetic, nature not just as a wellspring of vitality, but a forgotten religion, where plants, animals, and even frost crystals and bacteria are an extension of god.

“Many scholars feel that Muir’s baptism happened in California,” says Muir historian James Hunt, whose 2012 book Restless Fires examines Muir’s thousand-mile walk. “That’s just not true, it happened by walking through the South.”

A map of Muir’s 1867 journey, from his book A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

Ranger Travis Bow wears a tan uniform with a gun on his hip and a Muir-like beard. But before leading the way to the remote canyon where he imagines the derailment happened, Bow, who grew up on the Cumberland Plateau, a swath of steep forested ridges and sandstone cliffs in northeastern Tennessee, points out that Muir wasn’t too enamored with the local populace. Muir describes neighboring Jamestown as, “poor, rickety, thrice-dead…an incredibly dreary place.”

From a man whose pen breathed so much beauty, vulgar descriptions like this seem ill-fitting. Yet they characterize a part of Muir that gets little attention. While he revered the plants discovered on his walk to the Gulf, he rejected many of the humans.

“Muir dismissed people he thought were technologically backwards,” says Hunt. As counter-intuitive as it may seem, Muir was a technophile, “very much oriented towards the values of the Industrial Revolution.”

After all, Muir was an inventor. His mind’s gears turned towards efficiency and progress, a preoccupation shared by the nation. In a rabid quest for farmland and minerals, America had forgotten about the plants. Muir was there to remind them. “In the wake of industrialization,” says Hunt, “there is a moral purpose for wilderness.”

One of the sites of Muir’s walk, the Bonaventure Cemetery Savannah. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

Bow leads the way up wooden steps and onto a rocky finger of land that juts over a steep cliff like the prow of a ship. A gnarled bonsai-like tree arches delicately into the void, a Virginia pine, perhaps twice as old as the country. That night stars spill across the sky. Jupiter, Saturn and Mars are visible too, blazing like hot coals. Pickett State Park, recently named a “Dark Sky Park” by the International Dark-Sky Association is the darkest spot in Tennessee. The distinction, says Bow, once belonged to the Smokey Mountains, protected since 1940 as a National Park. But in recent decades, cities neighboring the park, like Asheville and Knoxville, have grown, and tarnished the once dark skies. National Parks were put aside for the people, and the people have come. This in turn has changed the wilderness experience.

Muir much preferred sleeping beneath the stars than under a roof. “Only by going alone in silence,” he wrote, “without baggage, can one truly get into the heart of the wilderness.” Yet, Yosemite’s Majestic Hotel—formerly the Ahwahnee—has a solarium, valet parking, and rooms, according to one luxury hotel website, “accented with original Native American designs.” Less than five miles from the rim of the Grand Canyon is a chalet-style hotel with an indoor pool and spa. The Furnace Creek Inn and Ranch Resort, in Death Valley National Park, the hottest place on earth, has an 18-hole golf course, spring-fed swimming pools and a stately dining room that serves steak, rabbit and omelets.

“I’ve thought many times,” says cultural critic Stefany Anne Golberg, via email, “that Muir’s project was almost too successful.”

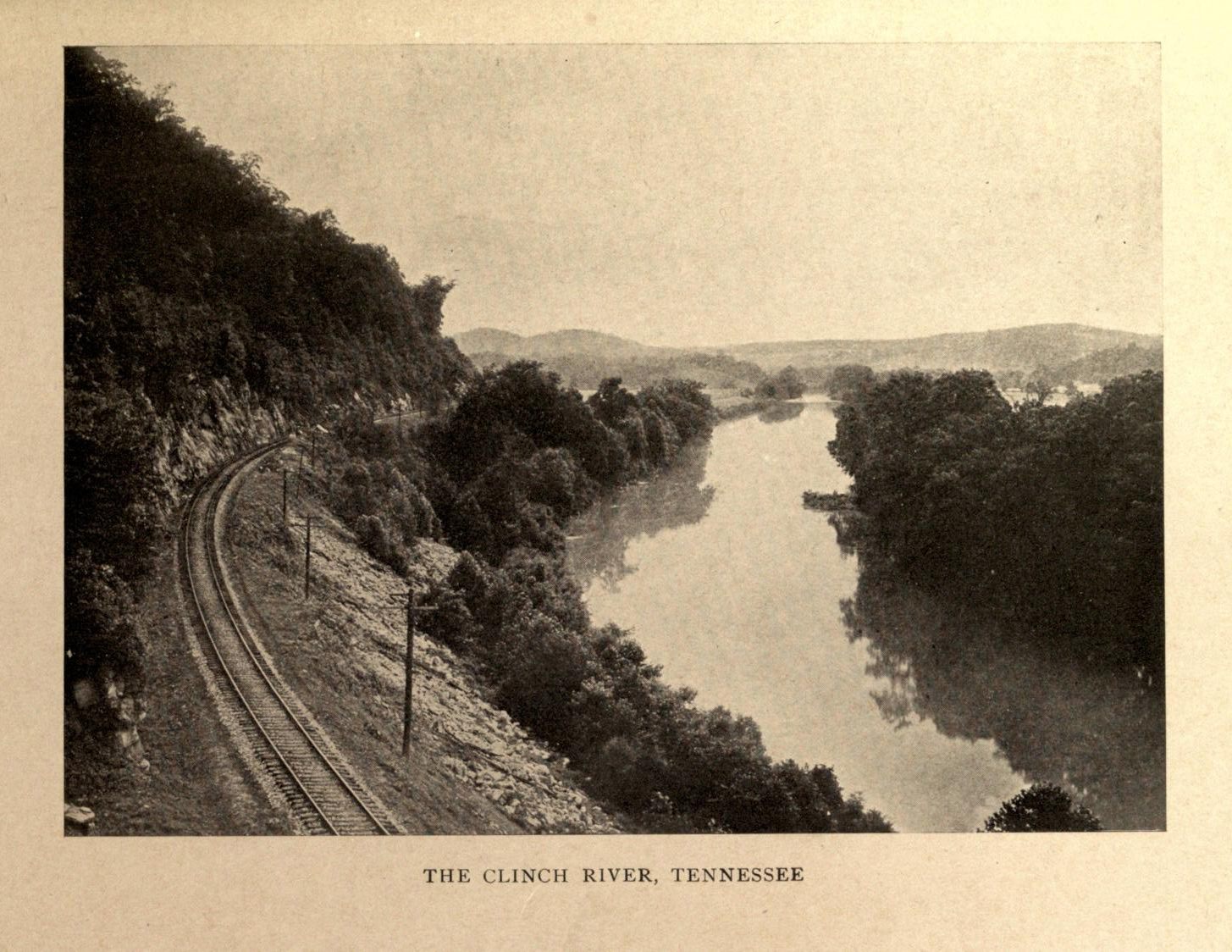

Muir crossed the Clinch River on his walk. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

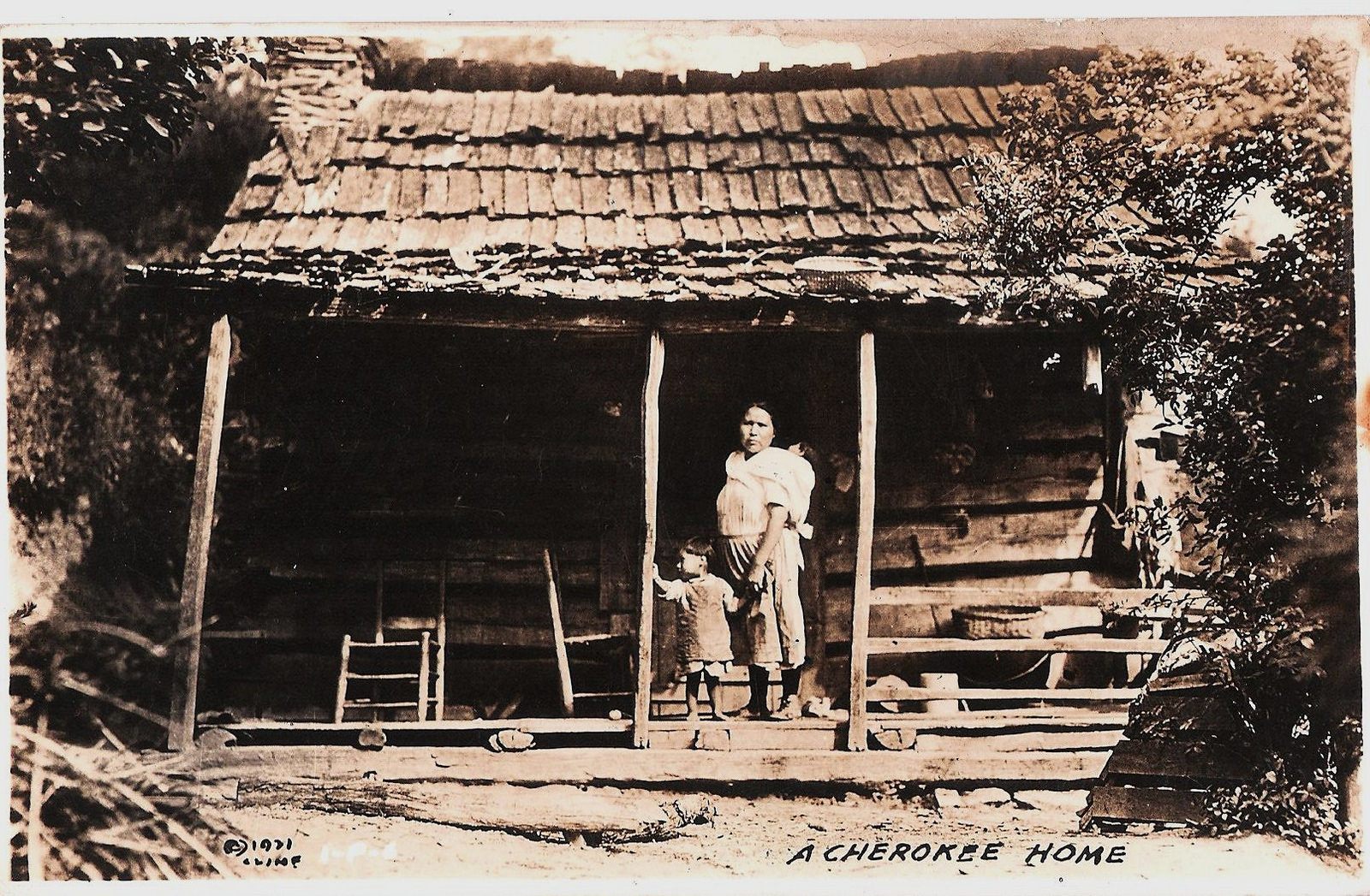

Whether or not Muir truly got lost in Pogue Creek Canyon, he made it out, climbed through the rugged mountains of southeastern Tennessee and eventually crossed the Hiwassee River, in North Carolina. The “very rough” channel and “leafy banks” impressed him. It was here, in the Smokey Mountains that in 1838 the Cherokee Indians were evicted from their homes in the dead of winter by white settlers’ hungry for their land and gold—even though a U.S. treaty and a U.S. Supreme Court decision guaranteed their land rights—and forced to walk more than a third of the way across the continent to Oklahoma, a march that would kill 4,000 people and come to be known as the Trail of Tears.

Muir, apparently, was ignorant of this history. He described the Cherokee homes he found as, “the uncouth transitionist …wigwams of savages.” He described the homes of the very settlers who may well have drove them out as, “decked with flowers and vines, clean within and without, and stamped with the comforts of culture and refinement.” For a man who supposedly walked with eyes wide open, this is a profound moment of blindness.

Today, the wigwams are gone, but the Cherokee aren’t, and on a recent June afternoon Sonny Ledford sits sharpening axes under a shade tree in front of the Museum of the Cherokee Indian. It’s a beautiful spot, hidden among deeply forested mountains, and has been occupied by Ledford’s tribe and their antecedents for more than 11,000 years. Ledford wears a pair of bear claw necklaces. Lightning-shaped tattoos streak his arms. His head is shaved, except for a ponytail of hair that sprouts like a plant from the middle of his skull. And as the hot June Smokey Mountain sun beats through the leaves, beams glint off his metal axes, and flash in the rapt eyes of the small crowd gathered around.

A photograph from around 1920 of a Cherokee home in North Carolina. (Photo: State Archives of North Carolina/Public Domain)

“Everyone out there is lost,” says Ledford, gazing past the mountains, toward the exurbs, the interstates, burger joints, malls, John Muir middle schools. “You go to college to sit in some class for four years so you can get some piece of paper that gets you some general manager position so you can do some job you hate, just so you can be fired for a reason you don’t even understand…forget that,” says Ledford. “I don’t need some piece of paper to tell me who I am, I have this,” and he holds up a sacred turtle rattle.

When asked what John Muir means to him, Ledford, after first having to be told who the man was, scoffs at the question. “My people commonly walked from here to Florida,” he says. “The difference is, we were all touched with that desire to be in nature, we just did it. And we didn’t glorify this one man.” Native American tribes, Ledford wants us to understand, were full of John Muirs, and between Spanish explorers, Christian missionaries and American settlers, a countless many John Muirs were killed. For Americans to idolize a figure who suddenly believed what his people had always believed was the ultimate irony. “We’ve accomplished so much that we don’t get recognition for,” sighs Ledford. “It has always been like that.”

In the Village Creek State Park in Arkansas, a portion of the Trail of Tears remains. (Photo: Thomas R Machnitzki/desaturated/CC BY 3.0)

Ledford is not alone. “This isn’t something that we are really jumping up and down about,” says a battle-worn Barbara Durham, historic preservation officer for Death Valley’s Timbisha tribe, when asked what John Muir and the National Park Service’s upcoming centennial meant to her. Durham’s community is located just downhill from the sumptuous Furnace Creek Inn and Ranch Resort. The Timbisha are the only Native American tribe that officially resides within the bounds of a national park, a privilege the tribe fought long and hard to guarantee—at one point park policy was to knock their earthen homes down with powerful hoses then take over the land. In 2000, just before leaving office, President Bill Clinton signed the Timbisha Shoshone Homeland Act, formally recognizing the Timbisha tribe’s right to exist.

But relationships remain tenuous. Durham says National Park Service officials recently asked her to talk at an upcoming centennial event. She refused. “It is their celebration,” says Durham, “not my celebration.”

This is the dark side of the Muir mythology, and one that was highlighted on his Southern journey. The man who thought of nature as a cathedral, and regarded, “whales and elephants, dancing, humming gnats,” and even “invisibly small mischievous microbes” as divine, regarded Native Americans as subhuman. Later, in California, he called them: “dirty,” “garrulous as jays,” “superstitious,” “lazy”. Such denigration is particularly surprising, as Muir’s spiritual embrace of nature could have been taken right out of a Native American mind. “Frankly, I think that is where he missed the boat big time,” says Hunt. “He totally missed the beauty and knowledge that Native American culture could offer, and what that could add to his own world view.”

Was Muir so caught up in Manifest Destiny that he refused to notice what came before? Was he so caught up with plants that he failed to notice who first tended them? Was he still under the influence of his parochial father, who once said, in a debate with a Wisconsin neighbor, “it could never have been the intention of God to allow Indians to rove and hunt over so fertile a country and hold it forever in unproductive wildness while Scotch and Irish and English farmers could put it to so much better use.” Or, was Muir’s aversion to Native Americans merely a product of his dislike for people he saw as technologically backwards? The distinction might not even matter.

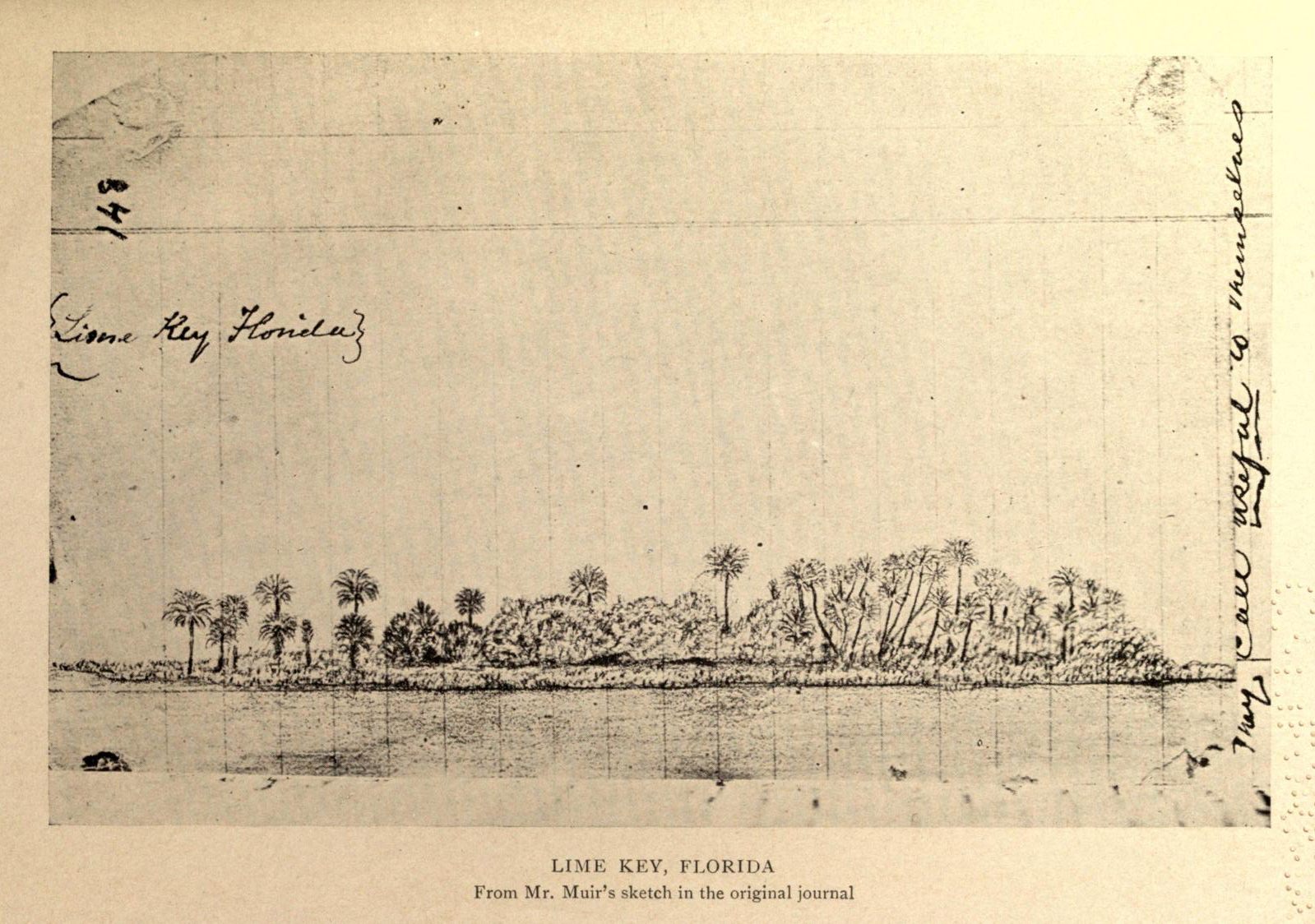

Muir’s depiction of Lime Key, Florida. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

On October 15, 1867, John Muir arrived in Florida via a steamship from Savannah, allowing him to bypass the Georgia coast—an “unwalkable piece of forest.” He immediately bought some bread, and darted into the woods, but the vegetation was so impenetrable that Muir could barely step off the path to inspect it. “Oftentimes,” he wrote, “I was tangled in a labyrinth of armed vines like a fly in a spider-web.”

Later, after a difficult night sleeping on a soggy hillock and out of bread, Muir spotted a shanty occupied by a logging party. “They were the wildest of all the white savages I met,” he wrote. Nevertheless, they shared with him a meal of yellow pork and hominy. Still, Muir remained skeptical of Florida’s swampy citizens. They were too poor, too dirty, too primitive.

“He really despised dirty people,” explains Harold Wood, an educator with the Sierra Club, the environmental organization Muir founded in 1892. “He couldn’t understand why people were dirty when bears and deer were not dirty.”

Outside of Gainesville, Muir came across the “most primitive of all the domestic establishments I have yet seen.” A couple was seated around a fire, in the ashes Muir noticed a “black lump of something”—it turned out to be a young boy. “Birds make nests and nearly all beasts make some kind of bed for their young,” wrote Muir, “but these negroes [sic] allow their younglings to lie nestless and naked in the dirt.” The following day the dirt parade continued, as Muir came to a hut, weary and hungry. “I saw only the man and his wife,” he wrote. “Both were suffering from malarial fever, and were very dirty…the most diseased and incurable dirt that I ever saw, evidently desperately chronic and hereditary.”

Death Valley National Park, where the Timbisha community resides. (Photo: Ken Lund/desaturated/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Those are hateful words, though not the sum total of Muir’s perspective. In other writings about his trip through the South, he sympathizes with African-Americans he meets, and bemoans the bigoted mindset he encounters amongst whites. His views on humanity, though, reflect deep ambivalence, and in nature, he seems to see a blank slate, a chance to write his own story upon the land.

The problem for Muir, for the National Park Service, for all of us, is that America was never a blank slate. And we know now Muir’s story was wrong. As new research by ecologists like Kat Anderson, of University of California Davis, shows, Native Americans in California, including those in Yosemite Valley, intentionally used fire to open land, increase pasturage, prevent even larger more catastrophic fires, and promote biodiversity. Muir’s sacred Yosemite was not a garden tended by God, as he wrote so passionately about, it was a garden tended by Native people.

Muir’s blurry human vision is something Native writers and historians have been grappling with for some time. “We do not know why Muir was blind regarding the original people in all of the beautiful National Park locations he waxed about so eloquently,” wrote Native author Roy Cook. “Indian people are the true conscience of the American character.”

It is also true that Muir’s views did change over time. He was 29 on his walk to the Gulf, and not much older when he first entered California. Later in his life, he traveled to Alaska. Muir lived among various tribes, including the Chukchis and Thlinkit. “He grew to respect and honor their beliefs, actions, and life styles,” wrote scholar Richard Fleck, in a 1978 article in the journal, American Indian Quarterly. “He, too, would evolve and change from his somewhat ambivalent stance toward various Indian cultures to a positive admiration.

As we sweat through summer, and laud this American hero anew and even cast him in gold, it is indeed important to remember his nature writing and his nature story. But it is equally important to remember, as we celebrate the creation of the National Park system and all of the beauty contained wherein, that a powerful story has already been written upon this land. It is sometimes the thing hiding in plain sight.

Update, 8/1: Due to a transcription error, we accidentally added an “s” to a quote, changing “people” to “peoples”. We regret the mistake.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook