The Secrets of America’s Best Rest Stop: Free Ice Water, Donuts, the Cutest Jackalopes in Town

A Wall Drug billboard (Photo: Jennifer Kirkland/Flickr)

A Wall Drug billboard (Photo: Jennifer Kirkland/Flickr)

Driving through South Dakota, it’s impossible to avoid Wall Drug. The billboards start before you even enter the state, and they’re arrayed, hundreds of them, alongside I-90, for more than 400 miles. They lure you like a tractor beam, and whether you intended to or not, by the time you reach Wall, odds are that you’re going to stop.

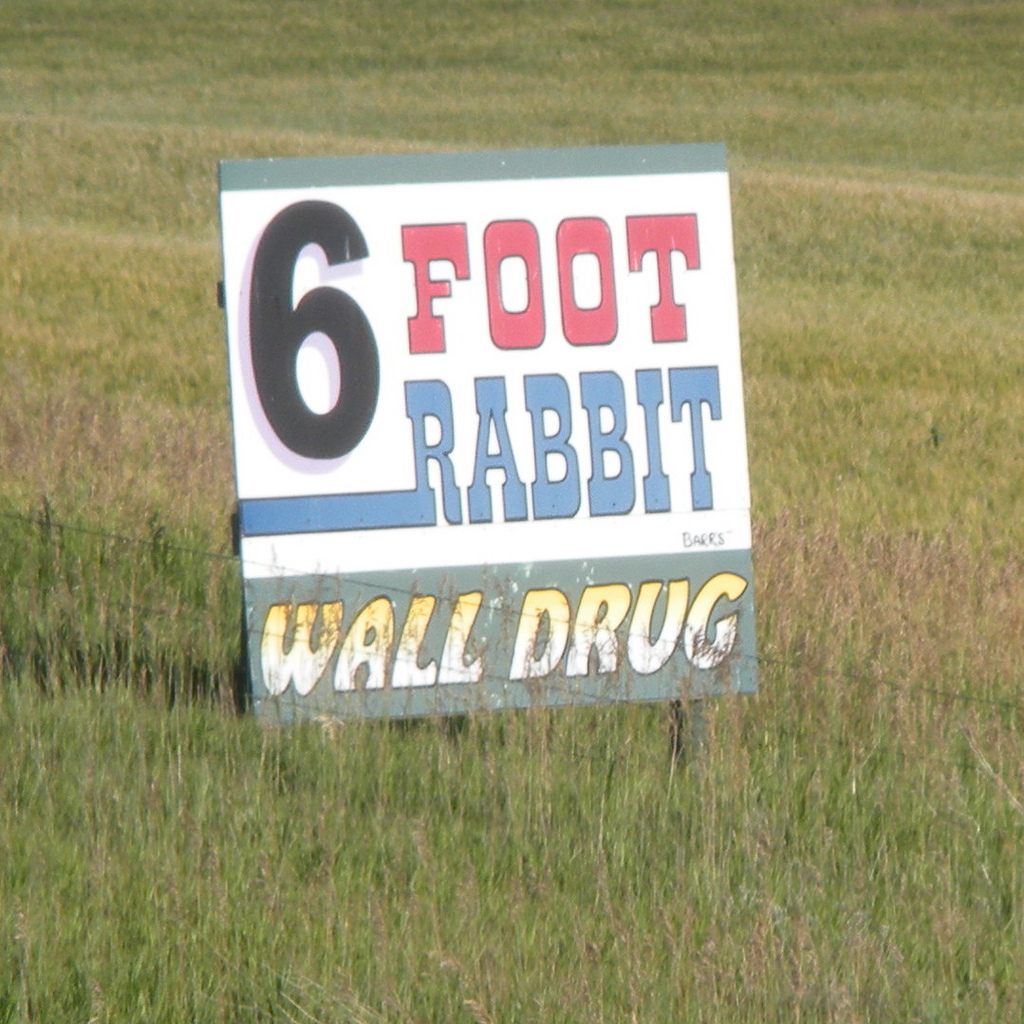

Another Wall Drug billboard (Photo: mr_t_77/Flickr)

Another Wall Drug billboard (Photo: mr_t_77/Flickr)

And another (Photo: mr_t_77/Flickr)

And another (Photo: mr_t_77/Flickr)

Billboards are the reason Wall Drug Store exists. Back in the 1930s, when the Hustead family was trying and failing to eke out a living running a small drugstore in the tiny town of Wall, Dorothy Hustead had a flash of inspiration: They would give out free ice water, and they would advertise it on boards flanking the highway.

It worked. The ride through South Dakota, in the summer, is long and hot, and the promise of a cool drink brought customers.

Ice, too, was something of a luxury. “When they first started operating free water, they were cutting the ice in the winter, and storing the blocks of ice between layers of sawdust in an ice house,” says Rick Hustead, Dorothy’s grandson and the current chairman of Wall Drug. “When my dad was little, he had an ice wagon, and he would take blocks of ice and sell them to people to put in their ice box.”

The original pitch (Photo: Jennifer Kirkland/Flickr)

The original pitch (Photo: Jennifer Kirkland/Flickr)

The billboards kept the drug store in business, doing well enough, even, to expand to a bigger space in the 1940s. But it wasn’t until 1951, when Bill Hustead, Rick’s father, returned home as a registered pharmacist that Wall Drug started growing into a kitschy, comforting mecca of roadside Americana.

Hitchhiking during the war, Bill would tell his rides he was from Wall, and they’d recognize it, as the home of “that little drug store with all those signs.” But Bill wanted the business to be better than a little drug store, to be something spectacular. “Bill had a vision for the drug store,” Rick Hustead says. “That people, when they stop at Wall Drug, they won’t be disappointed. He expanded everything.”

Today, Wall Drug is no longer a little drug store with a lot of signs. It’s the ultimate rest stop, where you can get coffee, donuts, buffalo burgers, cowboy boots, cheesy Western paraphernalia, and, yes, ice water. You can sit on a rabbit-deer hybrid called a jackalope, pose as a pioneer, or visit with a dinosaur. But the first secret of Wall Drug is still the billboards.

There are a lot of these (Photo: mr_t_77/Flickr)

There are a lot of these (Photo: mr_t_77/Flickr)

“We advertise heavily,” says Hustead. “That’s how we started in business and that’s how we stay in business.” But, he says, “Once people get here, we try to deliver. We don’t want them to be disappointed.”

We’re here! (Photo: m01229/Flickr)

We’re here! (Photo: m01229/Flickr)

Here we go! (Photo: Brendan Baker/Flickr)

Here we go! (Photo: Brendan Baker/Flickr)

In the summer, the day at Wall Drug begins with cooks coming in at 4:30 a.m. to start making Wall Drug donuts, and the other food the store will serve that day. There is still a drug store at Wall Drug, but it’s one of the quieter corners of the business. “Travelers, when they come to Wall Drug, they want to be able to get something to eat,” says Hustead. “They want clean restrooms. They want to look around. Maybe do a little shopping. Wall Drug is an experience.”

This is Wall Drug. (Photo: Brendan Baker/Flickr)

This is Wall Drug. (Photo: Brendan Baker/Flickr)

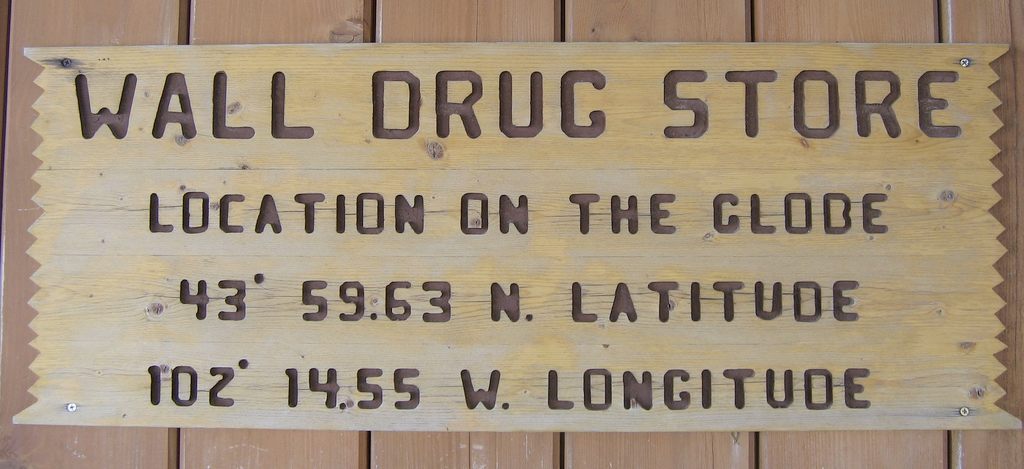

In case you were wondering (Photo: Liz Lawley/Flickr)

In case you were wondering (Photo: Liz Lawley/Flickr)

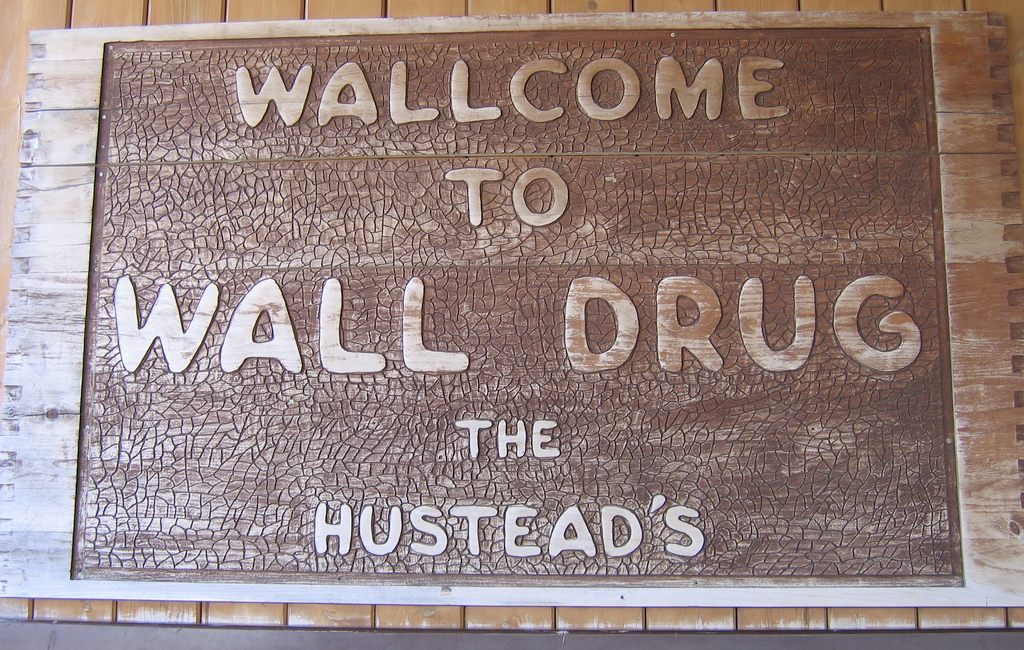

Wallcome! (Photo: Liz Lawley/Flickr)

Wallcome! (Photo: Liz Lawley/Flickr)

Inside Wall Drug (Photo: Qfamily/Flickr)

Inside Wall Drug (Photo: Qfamily/Flickr)

A tour might start in the restaurant. It seats 530 people, and it serves simple food, with a twist: Hot beef sandwiches are popular; so are buffalo burgers.

One unusual attraction of the restaurant is that it’s hung with a collection of more than 300 original paintings, worth millions of dollars, by Western artists including Andrew Standing Soldier, Harvey Dunn, and N.C. Wyeth. Bill Hustead had good taste: he bought most of the art before it was worth as much as it is today. “We couldn’t put together today the collection we have,” says Rick Hustead. “Bill was kind of drugstore cowboy. He was a pharmacist. He liked to ride horses. He had a taste for it.”

The restaurant (Photo: Britt Reints/Flickr)

The restaurant (Photo: Britt Reints/Flickr)

Bill Hustead also felt very strongly about the donuts. In the 1950s, he went to the West Coast to learn how to make them; he bought a donut machine; the recipe evolved over the years. (They come in maple, vanilla, and chocolate.) He told Rick that Wall Drug could never run out of donuts—that Wall would always offer free coffee and free donuts to military veterans, and, for that reason, they would always need them on hand.

A genuine Wall Drug donut (Photo: Jill/Flickr)

A genuine Wall Drug donut (Photo: Jill/Flickr)

In total, Wall Drug’s total sales rang in at $12 million last year, Hustead says; $3 million of that came from the restaurant’s gross sales.* But it’s one of the hardest parts of the complex to run. “One of the things that has driven us crazy this year is trying to find enough donut flour,” says Hustead. Their supplier had a hard time getting ahold of it. “You’d think getting those things would be simple. But sometimes they’re not.”

Coffee is just five cents. (Photo: Natalie Maynor/Flickr)

Coffee is just five cents. (Photo: Natalie Maynor/Flickr)

But ice water is free. (Photo: m01229/Flickr)

But ice water is free. (Photo: m01229/Flickr)

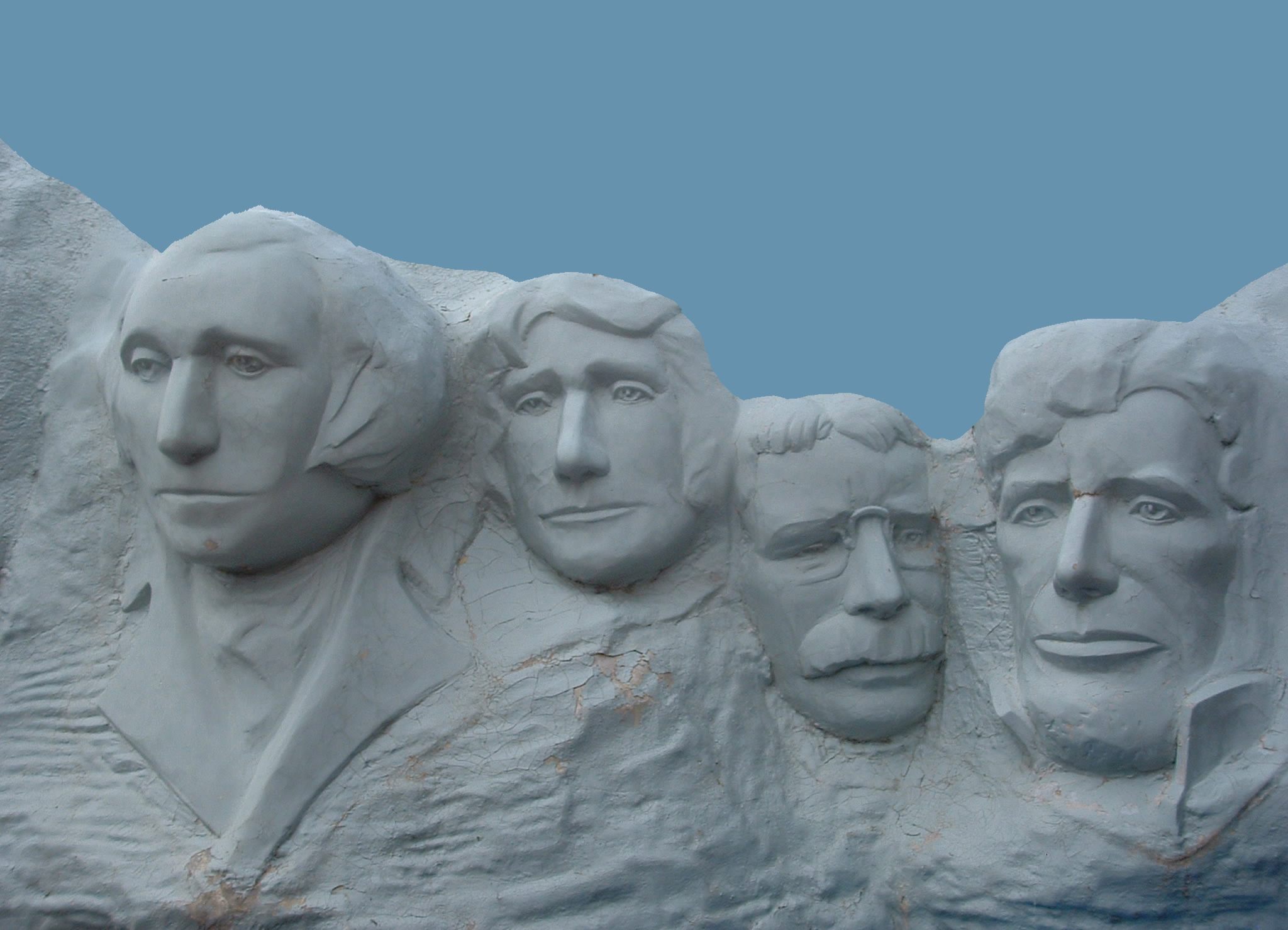

Most people who stop at Wall Drug spend a fair bit of time in the backyard, and take lots and lots of pictures. There’s a covered wagon to ride in, a mini model of Mount Rushmore. and those brightly painted boards that you can stick your face in and become a pioneer or stereotypically head-dressed Indian. The two main attractions of the backyard, though, are the giant jackalope and the T-rex.

Here it is—Mount Rushmore! (Photo: Sarah German/Flickr)

Here it is—Mount Rushmore! (Photo: Sarah German/Flickr)

Maybe not quite as cool as the real thing (Photo: Justin Baeder/Flickr)

Maybe not quite as cool as the real thing (Photo: Justin Baeder/Flickr)

“The T-Rex, really, he’s a standalone attraction,” says Hustead. “People go to see the T-Rex, and that’s mainly what we got him for. Because he’s pretty impressive.” In the summer, every 12 minutes, he rises his head up and roars. Smokes comes out of his nostrils. It’s not even close to terrifying; it’s exactly how you’d expect a mechanical T-rex in the middle of South Dakota to perform.

The T-Rex at rest (Photo: Jeri Gloege/Flickr)

The T-Rex at rest (Photo: Jeri Gloege/Flickr)

The jackalope, on the other hand, is both delightful and uncanny. It is an unusually tall specimen of a creature that doesn’t actually exist—a jackrabbit that’s somehow grown antelope horns. Jackalopes first started appearing in the west in the 1930s (always dead because, of course, they don’t actually exist in the wild), and they’re a staple of the Wall Drug experience.

This is a jackalope (Photo: Chris M Morris/Flickr)

This is a jackalope (Photo: Chris M Morris/Flickr)

You can ride it (Photo: Konrad Summers/Flickr)

You can ride it (Photo: Konrad Summers/Flickr)

Besides sitting on the jackalope in the back, you can buy one in the gift shop. Asked where the jackalopes come from, Hustead said, “We have a supplier. A closely guarded supplier.” There is, he allows, a lot of competition to supply tourists with jackalopes. “But ours are the cutest. And they have real horns.”

A jackalope, as real as they come (Photo: Jeri Gloege/Flickr)

A jackalope, as real as they come (Photo: Jeri Gloege/Flickr)

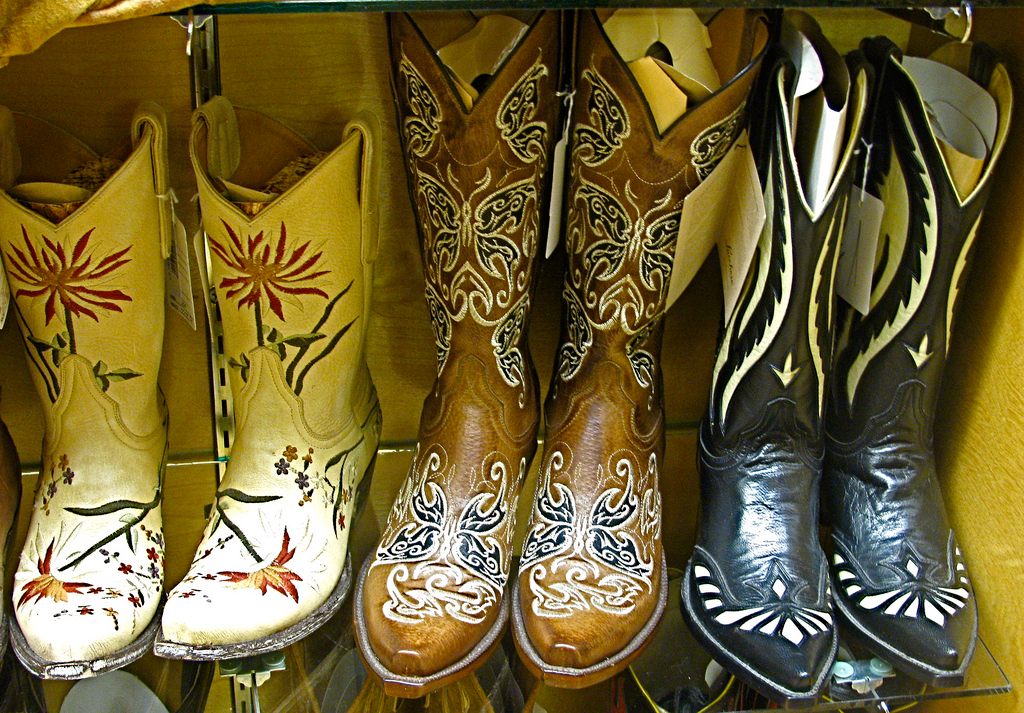

After the backyard, there are plenty of other options for entertainment. If you’re going to eat at the restaurant, Hustead recommends budgeting two and a half hours for the entire Wall Drug stop. There’s gold panning and mining. There are water shows, an arcade, and a country store with homemade fudge. You can buy t-shirts (one of the most popular items), shot glasses, coffee mugs, toy wooden guns, stuffed animals, caps—thousands and thousands of items. There are 6,000 pairs of western cowboy boots on display.

Boots (Photo: Susan/Flickr)

Boots (Photo: Susan/Flickr)

More boots (Photo: sellke/Flickr)

More boots (Photo: sellke/Flickr)

Hello, buffalo (Photo: Sarah German/Flickr)

Hello, buffalo (Photo: Sarah German/Flickr)

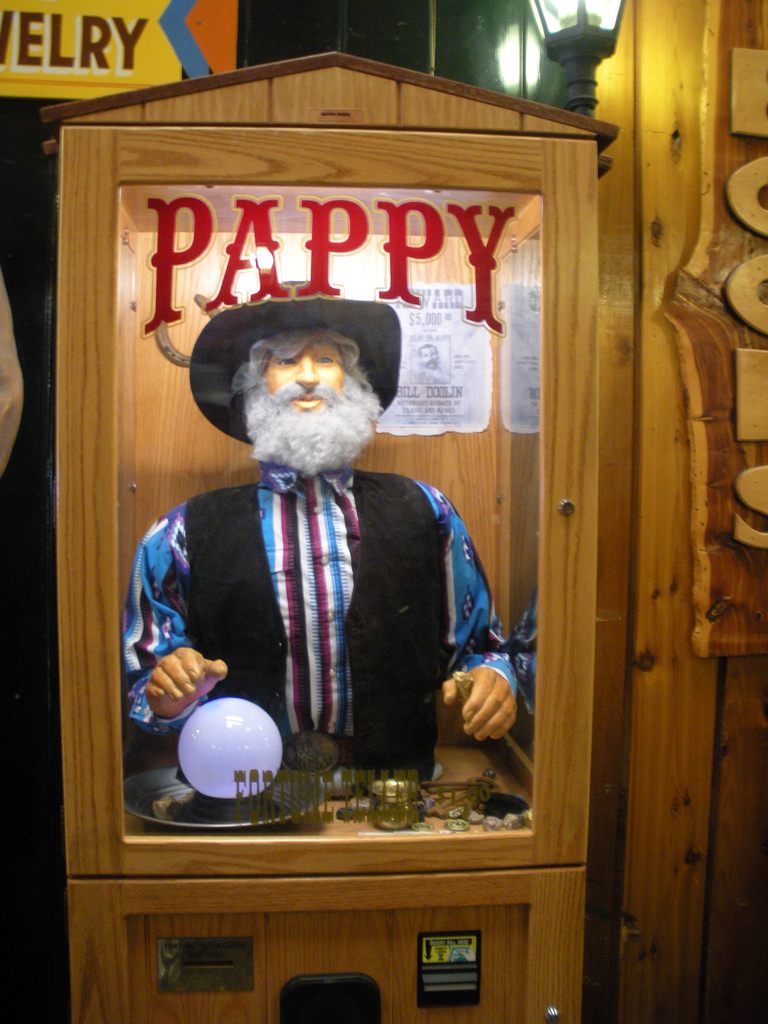

Pappy will tell your fortune (Photo: mr_t_77/Flickr)

Pappy will tell your fortune (Photo: mr_t_77/Flickr)

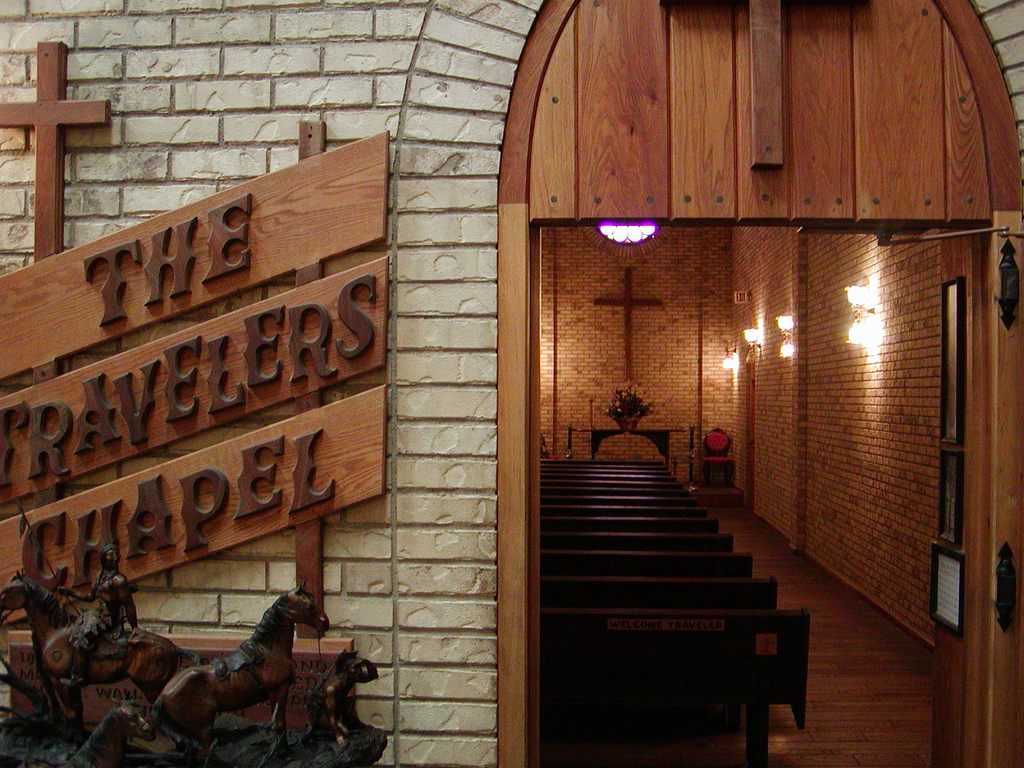

You can also buy a black powder pistol for hardly any mark-up. “We have them because you need to be able to go into a Western drug store and buy a black powder pistol,” says Hustead. “They’re real. They’re what they used in the Civil War.” You can also stop at the Traveler’s chapel, dedicated to religious leader who have served the area since 1909.

Traveler’s chapel (Photo: Qfamily/Flickr)

Traveler’s chapel (Photo: Qfamily/Flickr)

A hall of history (Photo: jvoves/Flickr)

A hall of history (Photo: jvoves/Flickr)

Just hanging out (Photo: Jennifer Kirkland/Flickr)

Just hanging out (Photo: Jennifer Kirkland/Flickr)

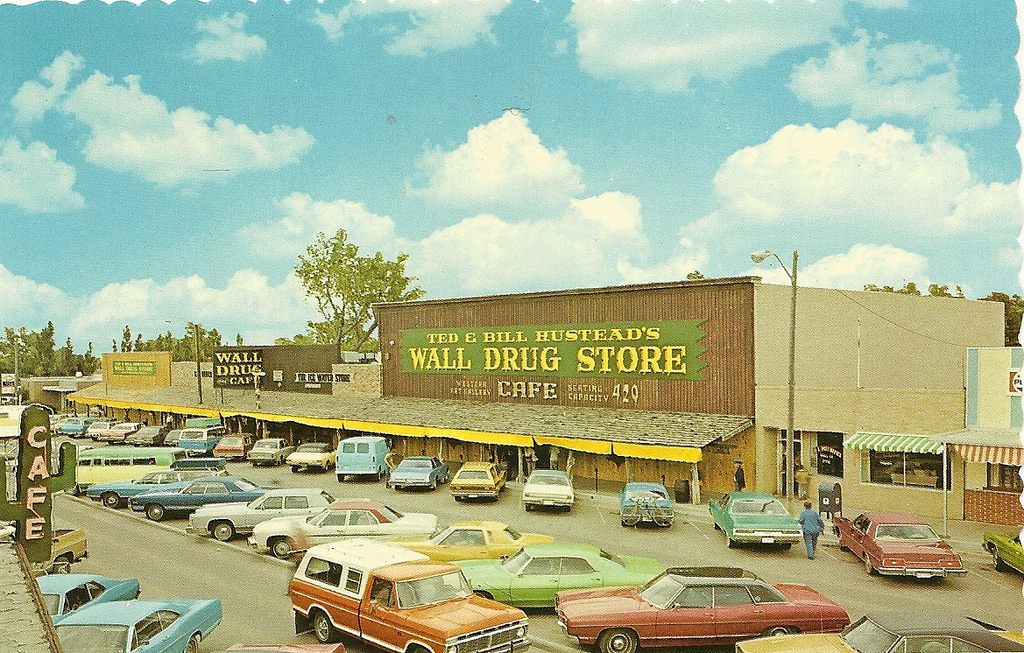

The real secret of Wall Drug is that not much has changed. The souvenir department was already going strong in the 1950s. The big expansion—half of the mall, the giant dining room, the backyard with the dinosaur—were all built before Rick Hustead came back home to work for the business in the early 1980s. “I just hoped that I could keep it up,” he says.

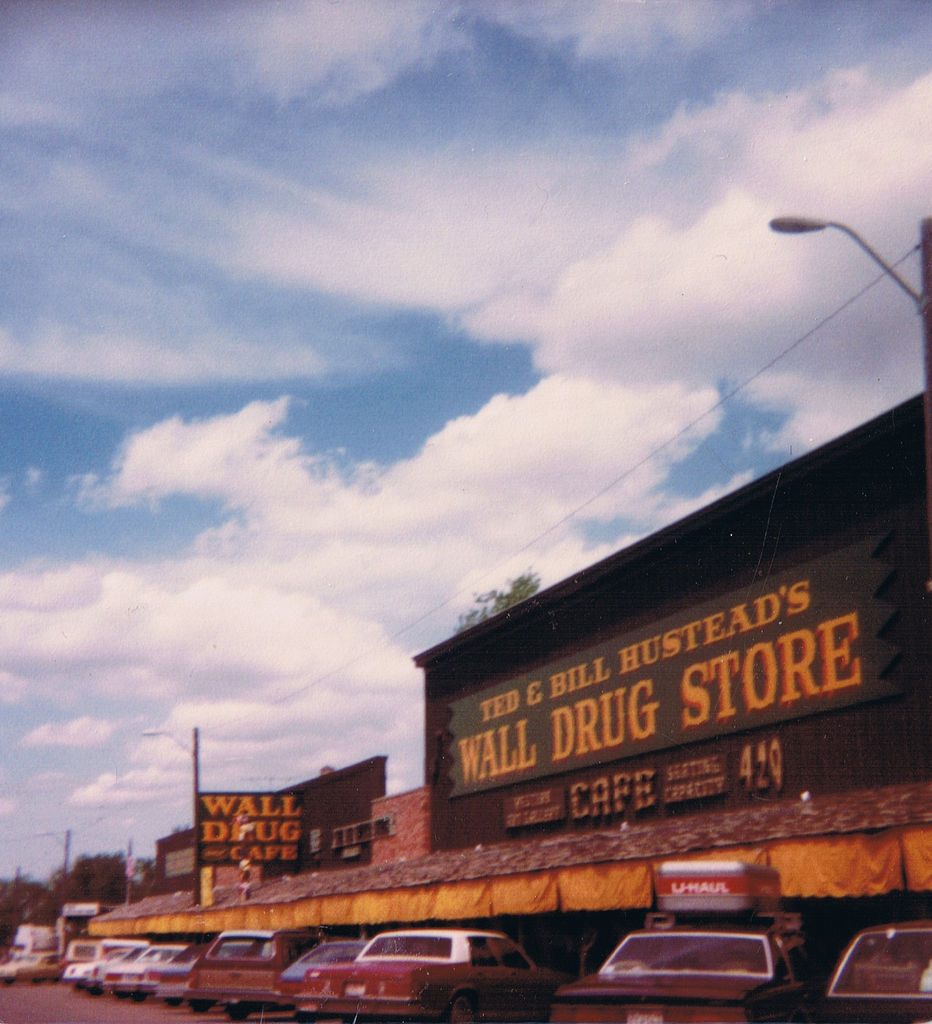

Wall Drug in the 1970s (Photo: John Lloyd/Flickr)

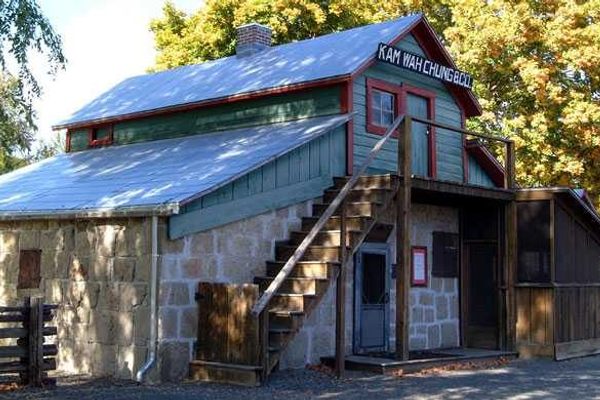

Wall Drug in the 1970s (Photo: John Lloyd/Flickr) Wall Drug in the 1980s (Photo: abbamouse/Flickr)

Wall Drug in the 1980s (Photo: abbamouse/Flickr)

This summer, Wall Drug has 212 staff people working, including Sarah Hustead, Rick’s daughter. Right now, they are bracing for the 75th anniversary of the Sturgis bike rally, a gathering of motorcycle enthusiasts in South Dakota’s Black Hills, on the western side of the state. In a less popular year, 450,000 bikers might come to the rally, and many of them stop at Wall Drug. This year, there could be as many as a million.

After that, though, Wall Drug’s season will start slowing. “We start losing staff right after the rally,” Hustead says. Employees go on vacation themselves; kids start heading back to school. In the fall, buses still come through, to eat, to drink, to shop, to rest, but by December, says Hustead, “things are pretty slow.” There are, he says, “all kinds of winter specials.”

Mainly, they’re trying to keep busy, until the season warms up again, and cars start plowing down the highway, full of people who are hot and thirsty and maybe in the market for a cup of free ice water.

So true (Photo: Kyle Taylor)

So true (Photo: Kyle Taylor)

(Photo: mr_t_77/Flickr)

(Photo: mr_t_77/Flickr)

(Photo: Kurt Magoon/Flickr)

(Photo: Kurt Magoon/Flickr)

(Photo: Kurt Magoon)

(Photo: Kurt Magoon)

*This sentence has been updated to clarify that Wall Drug’s total sales were $12 million, including the restaurant’s sales that totaled $3 million.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook