The Strange Tale of Echo, the Parrot Who Saw Too Much

A mobster’s pet is said to be in hiding. Could the bird be a witness in court?

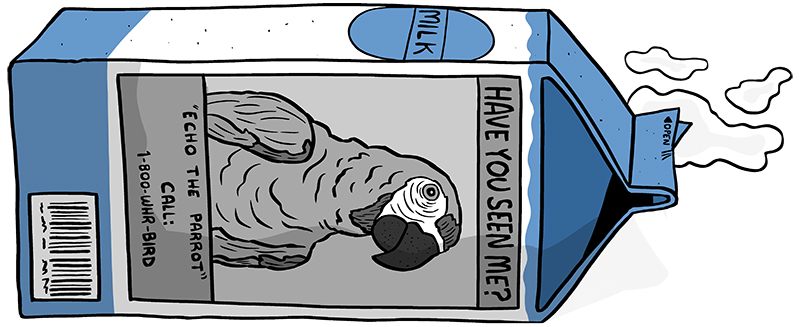

(All illustrations: Matt Lubchansky)

This story was co-produced with Digg. Digg curates the best of what the Internet is talking about. Check them out at Digg.com.

Recently, a friend of mine sent me a strange message. It was imperative, she said, that I get in touch with a guy named Geoffrey Mitchell. Geoffrey lives in the Bay Area and works for Caltrans—the California Department of Public Transportation. But before that, he worked as a marine biologist for the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries in the swamplands around Lake Charles.

That’s, he told me, where he heard about the parrot in a witness protection program.

Mitchell’s source was a woman named Suzy Heck, founder and director of an animal rehabilitation center called Heck Haven that takes in roughly 1,000 animals a year. When I called her, Heck explained that usually she rehabs wildlife like injured raccoons or orphaned baby squirrels, but every once in a while a different sort of animal shows up.

One afternoon in the mid-‘90s, she recalls, a wildlife rehabber friend of hers from New Orleans named Corina King arrived with a male parrot in a cage, a beautiful severe macaw—green with red shoulders—named Echo. He was medium-sized, a little thin and knew dozens of words. King told Heck that the bird needed to lay low for a while, and that she should keep his presence at the center a secret.

“It was all very hush hush,” Heck says, “and I didn’t know how long he was going to stay with me.”

According to King, Echo was owned by a New Orleans crime boss and he’d been at the wrong place at the wrong time, seen something he wasn’t supposed to, and wouldn’t stop talking about it. All this chatter, King told Heck, meant he was making himself into a potential target.

Because Echo isn’t a person, he couldn’t enter an actual witness protection program. At least not officially. At least not yet.

There are two reasons why it’s not that crazy to wonder if Echo could damage his owner’s case. First, throughout history, nonhumans like Echo have had starring roles in humanity’s legal theater. Animal defendants appeared in court as early as 1386 when a French pig dressed in a waistcoat and gloves was tried and publicly executed for murder and reached something of a zenith in late medieval Europe. This was a time when the distinction between humans and other animal species was particularly blurry—many people considered other creatures rational and capable of differentiating right from wrong. This made them culpable for their purported crimes and able to stand trial. There were sheep and donkeys convicted of having sexual relations with men, a rooster burned at the stake for supposedly laying an egg, and rats found guilty of stealing grain.

In certain cases, animals also provided important evidence for human trials. In 1647 in New Haven colony the aptly-named Thomas Hogg was convicted of buggery when a local sow gave birth to piglets that reportedly looked like him. Hogg refused to confess and so the governor of the colony brought him to the barnyard where he was forced to fondle the pig while the authorities watched. She appeared so “lustful” that Hogg was then forced to fondle a second sow as a control. That pig was reportedly less aroused. Hogg continued to deny all charges, and missing eye witnesses to the deed itself, the governor couldn’t make a conviction and deliver the standard punishment for sex with animals at the time—hanging. Hogg was whipped and jailed.

But what if the lusty pig had been able to speak? When we talk about parrots like Echo, we’re talking about an animal that possesses a trait that few others do: they can speak our language(s).

Many species of parrots are conscious, self-aware, and use language not just to communicate with people around them but also with one another. (A technical note: Being conscious is a bit different than being self-aware. For instance, a sea slug is likely conscious but perhaps not self-aware.) They can also use humor, understand complex categorization of the world around them as well as abstract concepts and ideas—like names for colors and the meaning of numbers. They are multilingual, intelligent and probably have their own moral sensibilities even if those sensibilities are different from ours. As for whether these capacities could make certain parrots reliable witnesses, why not? Humans definitely aren’t universally reliable and we can easily be taught to “parrot” something someone else wants us to say on the stand. In fact, parrots might even be less coachable in the courtroom than people who are intimidated or trying to protect themselves or someone they love.

Whether a parrot knows that he or she is opining on a court case is another matter. But very young children who might not understand their role in the legal system or the ramifications of their testimony have served as powerful witnesses too.

In fiction, the idea of parrots implicating criminals is common enough to be a cliché. It’s such a convenient plot device that it’s been used everywhere from Perry Mason, The Flintstones and Twin Peaks to Desperate Housewives, Friends and the James Bond film For Your Eyes Only. Here’s the parrot pretending to be James Bond with a fictional Margaret Thatcher:

There’s also the folk song—“Love Henry”—covered by Bob Dylan and, most spectacularly, by Nick Cave and PJ Harvey. It tells the story of a parrot named Henry who watches his mistress drown her husband and then hides out in the rafters so he’s not killed for being a witness.

“I won’t fly down, I can’t fly down

And light on your right knee.

A girl who would murder her own true love

Would kill a little birdlike me.”

Certain species in particular, can be spot-on imitators of the sounds around them—from the mundane cell phone conversation of their owners to calling the family dog by name (around 23 seconds in) and then bark just like them. They can mimic the beep of a microwave or a cell-phone ring so closely that it’s confusing. Sometimes they mimic other things people do too.

Occasionally parrots learn to mimic darker things. In South Carolina in 2010 a woman went to jail for abusing and neglecting her elderly mother. When local police entered the house they found a parrot that repeated “Help me, help me” —then laughed. They believed the parrot was mimicking the mother’s pleas, then the daughter’s laughter.

Sometimes parrots can be roped into criminal activity themselves. In September of 2010 in the Colombian city of Barranquilla, a parrot named Lorenzo was taught by his owners, members of a Cali drug cartel, to say “RUN, RUN” when he spotted the police. Lorenzo was guarding a load of guns and marijuana. He wasn’t prosecuted.

The few contemporary American cases where parrots have popped up in investigations haven’t resulted in convictions. In 1993, Charles Ogulnick, then a public defender in Santa Rosa, California, defended a man accused of murdering his business partner, a 36-year-old woman who was killed in her house. Max, her African grey parrot, was the sole witness to the crime. After she died, he went to stay with the owner of local pet shop, who told the cops that Max wouldn’t stop saying, in the voice of his owner “No Richard, no no no!” Ogulnik’s client’s name wasn’t Richard so he wanted the parrot’s testimony. Ogulnik went as far as contacting the parrot cognition and language expert Irene Pepperberg, who told him that birds like Max can be reliable tape recorders of things they overhear, but probably need to hear something more than once to accurately repeat it.

This wasn’t convincing enough for the judge assigned to Ogulnik’s case and Max’s outbursts weren’t entered into evidence. Ogulnick’s client was convicted and is currently serving a life sentence. After the trial Max was adopted by a woman fiercely dedicated to protecting his privacy and according to Ogulnik, stopped making him, or any information about him, available to the media.

So parrots haven’t thus far been participants in legal actions. But could they? Loopholes that allow parrots (or least what they have to say) into the courtroom might exist. Erin Murphy, a law professor at NYU, says that a parrot can’t be denied testimony, at least on the basis of hearsay, because hearsay can only be presented by a person. Something a parrot says could be admitted as evidence, in her opinion, but she’d never heard of it happening. Matthew Liebman at the Animal Legal Defense Fund, an expert on animal law, told me that parrots can’t be witnesses because they’re not people, but also because, in many states, you’d have to prove that a bird could tell right from wrong, and then take an oath about it.

But there is a movement afoot that could radically redefine who gets legal standing in the United States—and this might affect who (and what) can eventually stand trial. The Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP) has been working state by state within the American legal system since 2007 to shift the status of certain animal species from “things” to “persons” under the law. This designation would create a new category for nonhuman animals in the U.S., used to ensure adequate welfare protections—and NhRP is starting with the most cognitively complex creatures, such as elephants, great apes, dolphins and whales.

Steven Wise, lawyer and founder of NhRP, doesn’t believe that personhood designations would make it possible for animals like talking parrots or signing chimpanzees to act as witnesses in court cases. He is convinced however that a signing ape or a talking parrot should be able to provide key evidence in a case if he or she could be interviewed somewhere less stressful and overwhelming than a courtroom.

“Courtrooms are high tension places,” he says, “and animals will really pick up on that. But if a young child can testify then a communicating chimp should be able to as well.”

Other countries have been slightly more open to putting nonhuman animals on the stand, particularly France. In 2005, a judge in Nanterre ordered a veterinarian to show photos of two murder suspects to a Dalmation who’d belonged to the female victim, and gauge his reactions. Based on the dog’s response, the vet testified that he likely knew the killers. Three years later, also in a France, a 59-year old woman was found dead in her apartment and the only confirmed witness: her dog. The police suspected suicide but the family requested an investigation. So during a preliminary hearing the judge watched as the woman’s dog was led to the stand by a veterinarian and then a suspect was brought before him. The dog barked but the judge decided the barking was inconclusive.

Then, in 2014, a nine-year-old Labrador named Tango who belonged to a murdered man in the French city of Tours, was called to the courtroom to determine whether he’d react to a suspect raising a bat menacingly in his direction. The court then brought a second dog, a nine-year-old lab named Norman, in as a control, and asked the suspect to raise a bat against him too. The experiment was deemed inconclusive.

These cases raise complicated questions about who gets to speak, literally and metaphorically, for themselves, and whose rights are enforceable and to what extent. If organizations like the Nonhuman Rights Project are successful at establishing nonhuman personhood, could these creatures gain not only further protections but also become responsible for their behavior under the law, that is, tried for possible crimes or forced to testify against their owners?

If so, we might not be ready to hear what other animals have to say. The U.S. Navy probably doesn’t want to hear directly from dolphins and whales on the effects of its’ sonar use, the oil and gas industry certainly doesn’t want to have to talk to them about seismic testing, and Cargill and Tyson likely wouldn’t be interested in millions of depositions by factory-farmed pigs and chickens.

Echo the parrot lived with Heck in New Orleans for nearly a year. She told me he was usually a pretty happy bird. But sometimes late at night, when she was in another room, she’d hear the sound of a child loudly crying, then moaning, then a giant THWACK. Then, worst of all, a kind of maniacal laughter. She’d rush into the room to see Echo swaying back and forth on his perch, now quiet.

This made a certain sick sense to Heck because King had told her the crime boss was under investigation for child abuse.

It’s possible that Echo just liked to make those sounds. If not though, like Irene Pepperberg told the defense attorney Ogulnik, Echo probably heard the crying, moaning, thwacking, more than once. In fact, it’s pretty common for a parrot to mimic a crying baby.

Sometimes parrots like Echo are collateral damage to crime, witnesses but also unwitting victims. Police and animal control officers frequently bring Heck birds in the wake of drug busts, when their owners are sent to prison. (Exotic pets have long been prized possessions of drug lords and dictatorial types used to intimidate enemies or flaunt their owners’ wealth—from King John’s lions in the Tower of London to Mexican druglords’ big snakes and tigers) Sometimes their parrots are addicted to methamphetamines and Heck has to put them through detox. “The birds go through withdrawal and it’s horrible,” she said. “They’re suffering so much, it’s like they’re trying to kill themselves.”

The parrots fly at the sides of their cages, wild eyed, and then get up on their perches only to fall right off again. Or they act depressed, sitting in the corner of the cage, staring at their feet. “You can’t see sweat on a bird, but when you think of what people go through I think it’s similar—one minute they’re sleeping a lot and the next they’re crying out and beating their heads against a wall.”

One of her current charges, a small conure parrot, came to her after a sheriff raid on a local meth lab. Since getting off the drugs he’s never been quite right in the head—turning from happy and calm to angry and frustrated in a split second for no apparent reason. “You’d think people would remember that old saying about canaries in the coal mine,” she said.

The trail of Echo, though, has run cold.

A year after bringing him to Lake Charles, wildlife rehabilitator King came back around for the bird. It was time to move him on again, this time to somewhere in Texas. I tried to find Echo myself, through a network of parrot rescuers as well as by writing and calling every “Corina King” in Texas and Louisiana and a few other states too. None of them could tell me about a parrot in hiding. According to Heck, the crime boss who’d owned Echo was eventually convicted but I wasn’t able to verify that. One notorious mobster was arrested in New Orleans in 1994—Anthony Carolla—boss of the New Orleans crime family and son of another mob boss, “Silver Dollar Sam,” with ties to both the Gambino and Genovese crime families but it’s not clear that he ever owned a parrot. He was arrested along with four other men in a predawn raid after a two-year FBI and Louisiana State Police investigation. All of the men were indicted on racketeering charges. If Carolla was also under investigation for child abuse and the case was handled as a sex crime concerning a minor, the details could have been kept out of the media. (Although the rules require shielding for the child, not the accused.) Any records of the case would be in the archives of the New Orleans sex crimes unit, currently under Federal oversight due to corruption. Records of Echo’s involvement in the case might also be at the District Attorney’s office, but then again they might not be. The New Orleans DA from 1973 to 2003 was Harry Connick Sr. (father of Harry Connick, Jr., the singer and actor) and, along with his prosecutors, Connick has been accused of withholding and destroying evidence, racketeering, and other things you might not want a talking-parrot to witness.

Echo’s murky origin story is frustrating; while I don’t think Heck fabricated her story, I’m still trying to find the right lawyers who could finger his owner. But whether or not Heck precisely remembered all the details of Echo’s past might not matter. He wasn’t the first parrot to see something he wasn’t supposed to and start talking about it, and he isn’t the last. We don’t even know if he’s the only bird that’s been hidden for repeating damaging phrases. As our understanding of animal consciousness, morality and cognitive abilities grows, we’re going to encounter more thorny questions about who is capable of telling their own particular truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth, species be damned.

I asked Heck if she’s ever had another parrot brought to her under the cover of darkness, or in a sheet-covered cage, with a brand new name and a past she couldn’t question. She said it hasn’t happened, at least not yet. When she got Echo, she thought he was a young adult. Given that the average lifespan of Severe Macaws can be 50 years or more, it’s likely that Echo is still alive, sitting on a perch in a room somewhere, mimicking the sounds of a terrible crime.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook