The Victorian Tool for Everything From Hernias to Sex—a Vibrating Electric Belt

How a medical invention abused the electrotherapy fad.

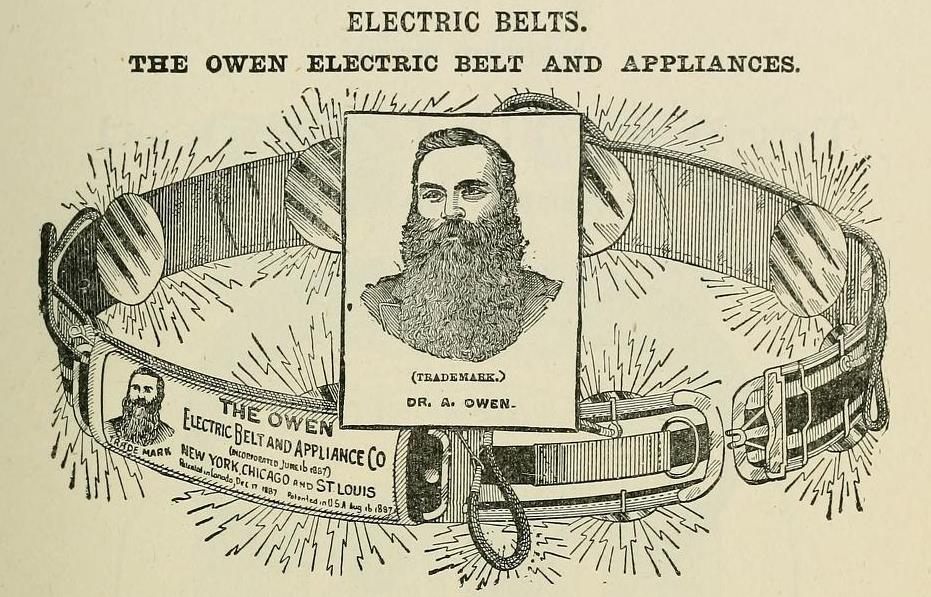

The electropathic belt was one of the most popular consumer medical products on the market during the 19th century. [Photo: Arallyn!/CC BY 2.0]

During the Victorian Era, or the “Electric Era,” as it was referred to in many advertisements of the time, new inventions like the electric telegraph and electric lights were quickly changing day-to-day activities for the general public. But beyond these practical household devices were the rather more dubious electrotherapeutic inventions that tried to harness that thrilling buzz for the sake of beauty and health.

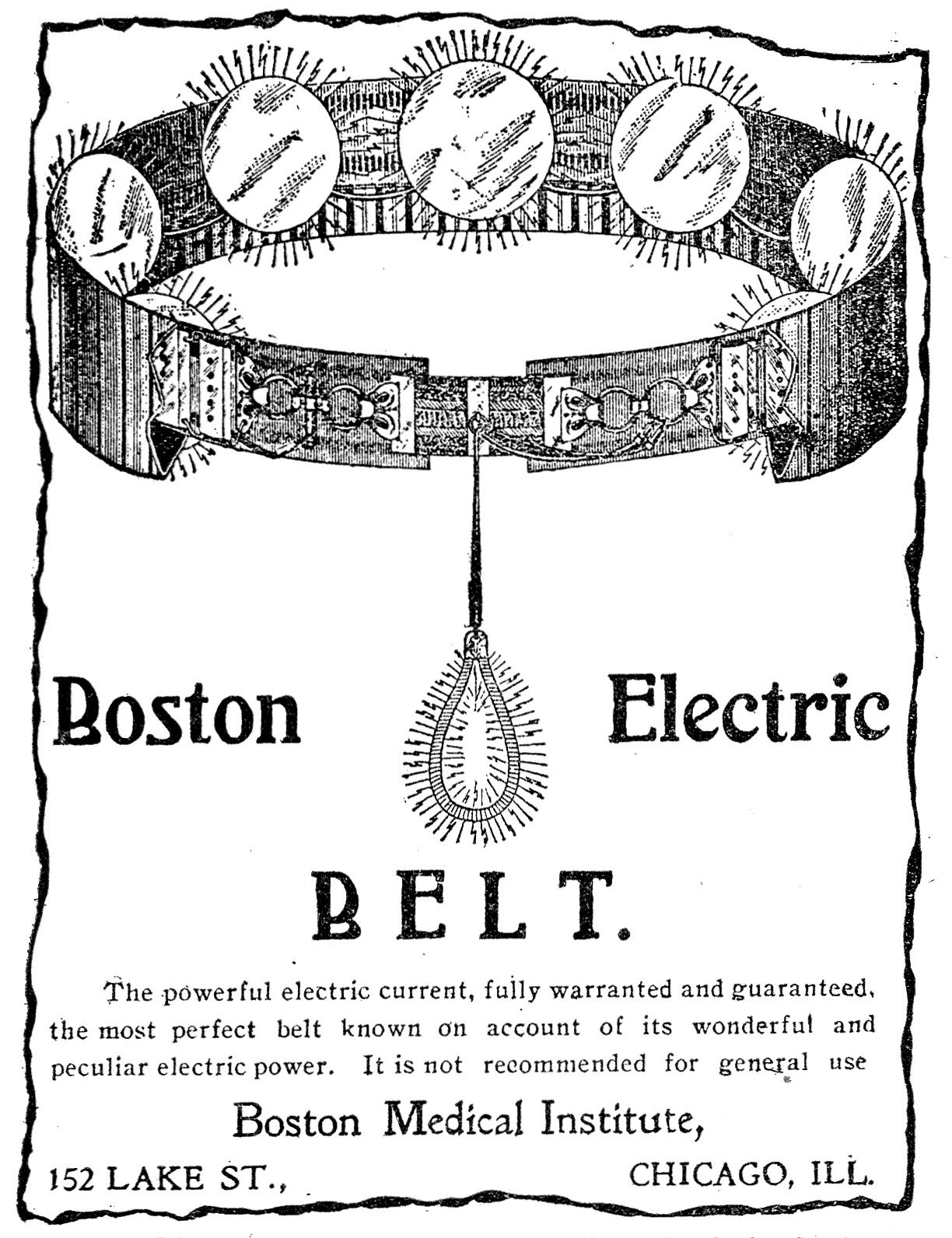

Convenience stories and advertisements were filled with commercial, electric-producing medical items from hairbrushes, socks, corsets, to wristlets. But, one of the most popular and scandalous inventions of the Electric Era was the electropathic belt—a contraption of silver-coated zinc, copper coils, and wires that surged the body with small dosages of electricity.

“The intimacy with which they came in contact with the body and the sophistication of their design and advertising materials made belts particularly influential objects for consumers with little electrical knowledge and great electrical enthusiasm,” wrote University of California Davis American studies professor Carolyn Thomas in the Journal of Design History.

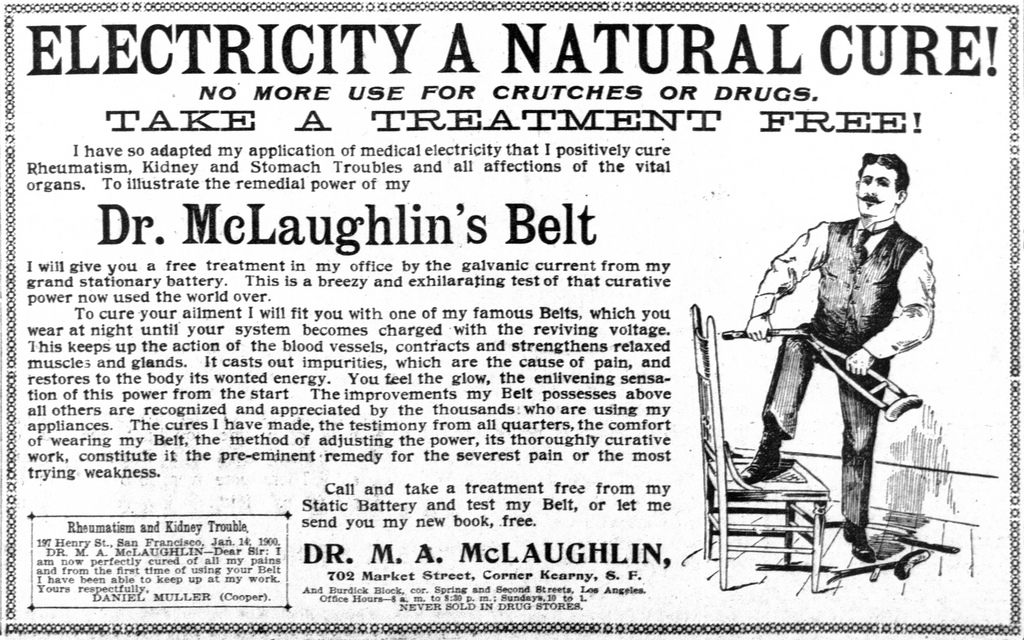

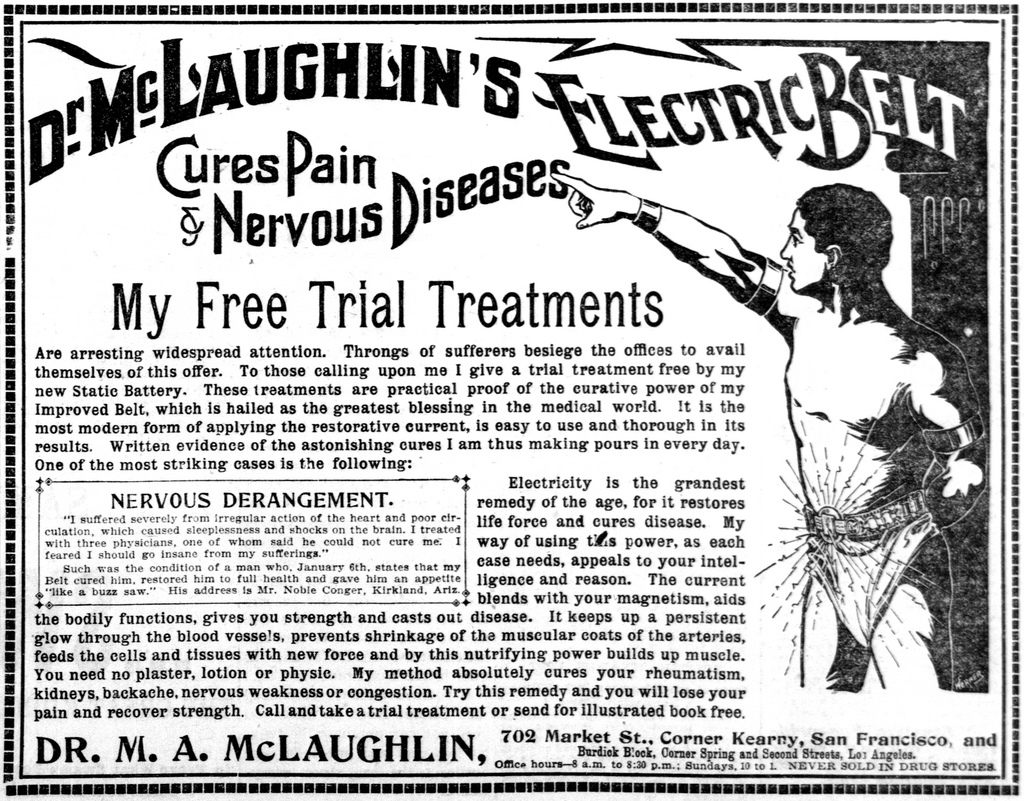

This advertisement says Dr. McLaughlin’s Belt should be worn at night until your system becomes charged with reviving voltage. [Photo: India Amos/CC BY 2.0]

Electric treatments and therapies were thought of as one-stop cures for practically all ailments and maladies. Doctors and scholars practiced and taught electrotherapy since the mid-18th century in hospitals around Paris and London. By the 19th century, devices became smaller, more portable, and easier to operate, giving way to a wave of battery companies that produced electric-based health products. General medical commodities, including products like the electropathic belt, easily made up 25 percent of all advertisements by 1880, University of Toronto history professor Lori Loeb estimates in an article in the Journal of Victorian Culture.

“There was some valid use for electricity such as cauterization, resuscitation, and treatment of pain and paralysis,” Robert Kravetz wrote in a review in The American Journal of Gastroenterology. “But 99 percent of the myriad of instruments were quackery.”

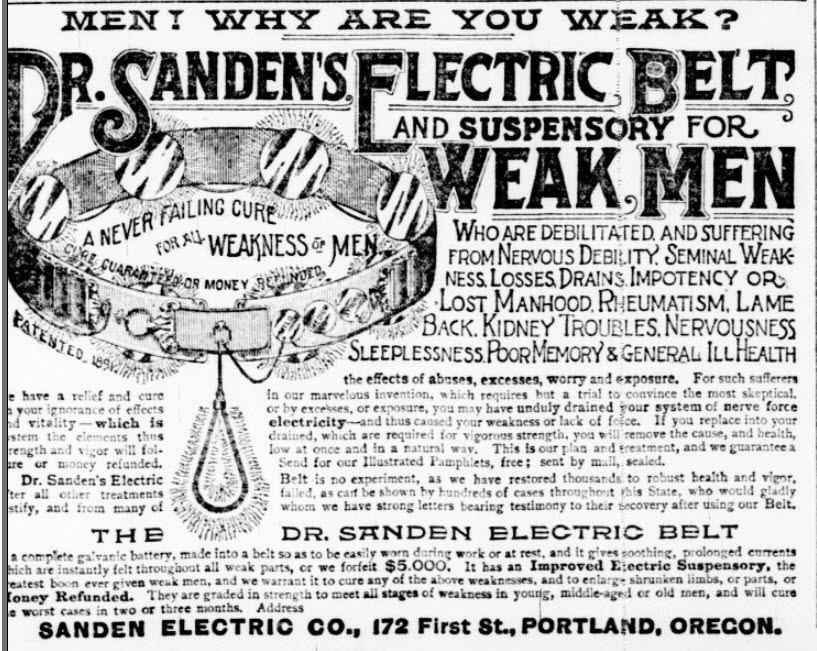

An advertisement for Dr. Sanden’s Electric belt and Suspensory for Men featured in an 1892 Seattle, Washington paper. [Photo: Washington State Library/Public Domain]

The electropathic belt (also known as the “electric belt,” “electric chain” and “electro-galvanic belt”) was one of the most popular, according to Kravetz. Despite the British Medical Journal’s early criticism of one of the leaders in electropathic belt manufacturing (which featured the phrase ”egregious quack”), tens of thousands of electric belts were sold in the United States alone between the 1890s and the 1920s, and it was even listed in a 1906 Sears catalogue.

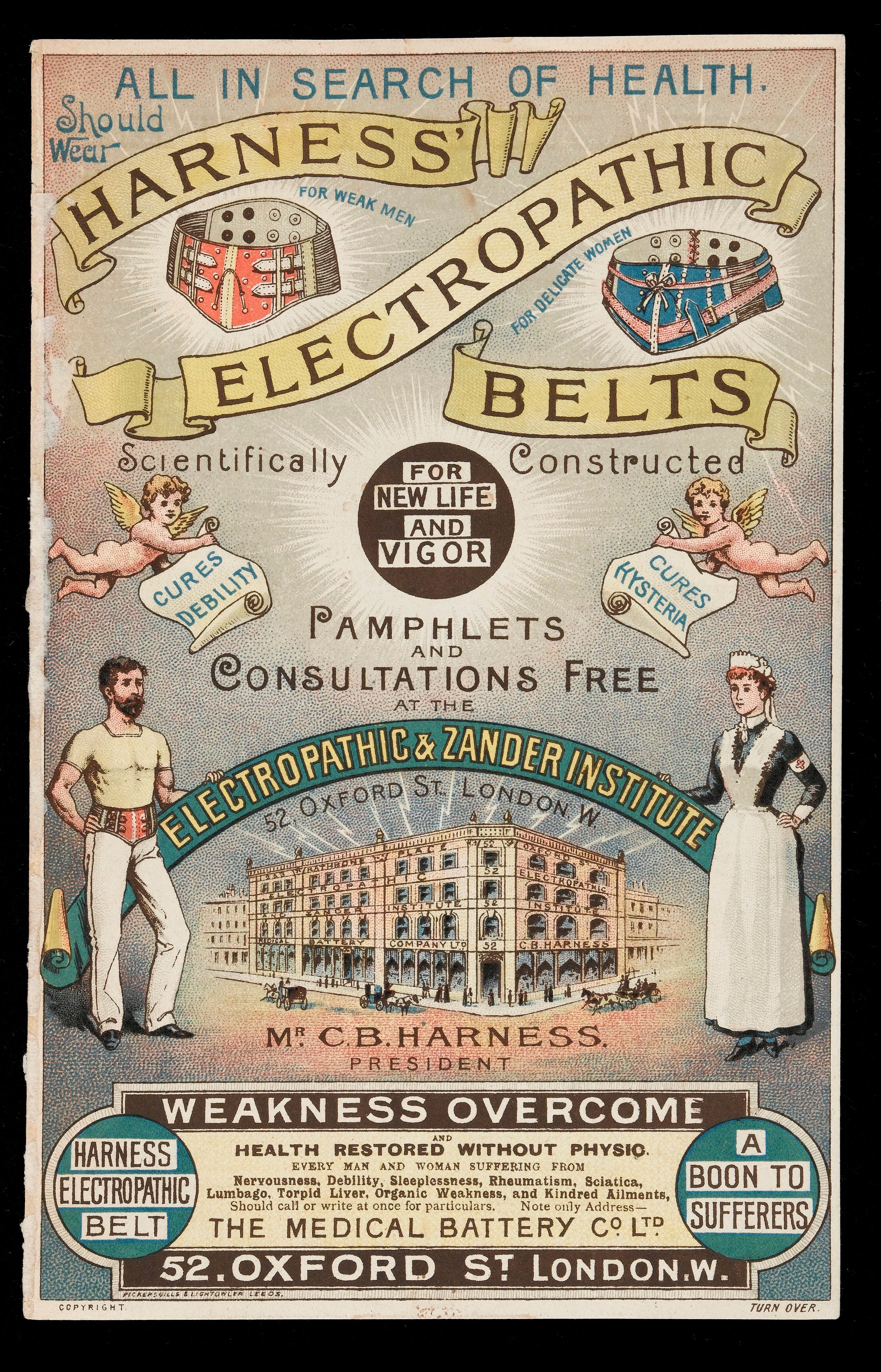

Companies fought to win the “battle of the belts,” as Loeb describes. They were notorious for pushing out elaborate and lavish advertisements depicting muscular men, beautiful women, and flying cherubs. The pictures were flanked by testimonials from actresses and leading doctors which said the belts generate “an exhilarating health-giving current to the whole system.”

A colorful advertisement produced by The Medical Battery Company, which was founded by Cornelius Bennett Harness. [Photo: Wellcome Library, London/ CC BY 4.0]

The device was meant to treat all known diseases and illnesses including exhaustion, impotence, dyspepsia (indigestion), liver disease, nervous disorders, heart disease, hernias, and unsatisfactory sexual performance. One iteration by the Pulvermacher Galvanic Company sported an electrically charged pouch called a suspensory sack:

“In our treatment the Suspensory gives the necessary support to the scrotum; at the same time the electric-curative currents, which may be said to envelop the suffering parts, gradually equalize the circulation of blood in the enlarged veins, and effect a permanent cure.”

Some belts, like the Boston Electric Belt featured in this advertisement, featured pieces said to benefit sexual activity. [Photo: Wellcome Library, London/CC BY 4.0]

Belts were made accessible to a wide customer base. They came in different sizes for both men and women and were priced between $4 to $18. Some belts had a wet sponge or batteries to help the flow of electricity, but most were designed to generate electricity from the wearer’s sweat and the zinc discs.

Electropathic belt manufacturers continued to reap money from consumers until the Medical Battery Company, one of the leading companies in London, started to unravel under a series of scandalous, heavily publicized court cases.

Cornelius Bennett Harness, a former jeweler and furniture salesman, billed himself as a “medical electrician” and founded the Medical Battery Company in 1885 after developing a business in electric hairbrushes in New York. In 1892, a male cashier at Union Bank sued Harness for fraud after using the belt to cure his hernia which became worse the more he used the device. The cashier won the case, and soon after the Medical Battery Company was bombarded with press investigations and trials by a range of customers (from rich upper class citizens, to servants, and common soldiers). One trial had over 400 witnesses appearing at a prosecution.

Belts were also said to help “feminine illnesses.” [Photo: Wellcome Library, London/CC BY 4.0]

The investigations revealed that the belts’ currents were so minimal that they hardly registered on galvanometers, a measuring instrument commonly used in the 1800s by electricians. Many of the testimonies were found to be fake. The belts also had a harmful side effect on the skin as the zinc and copper discs left behind corrosive salt that caused sores.

Harness initially ignored people’s complaints about skin irritation. He told customers to wear the belt over a thin garment for a couple of days and the irritation would quickly go away.

Harness was accused of having no understanding of electricity. It turned out he had erased someone else’s name from an official-looking certificate that claimed his credentials. His claim that he was president of the British Association of Medical Electricity was true—but only because it was an organization he created himself.

Harness’ response to his company’s demise and the attacks from the press was that it was “un-English” and “cruel.” The Medical Battery Company went bankrupt in 1895, but Harness tried to start a similar company, Medical Electrical Institute Ltd., nine months later that quickly failed.

A 1900 advertisement for Dr. McLaughlin’s Electric Belt which claims to cure pain and nervous system diseases. [Photo: India Amos/CC BY 2.0]

“By the end of 1895 Harness belts were deemed so worthless that two leading drug stores were offering them at 75 percent reduction,” Loeb wrote in the Journal of Victorian Culture. “His initial success conforms with the manipulative model of consumerism, rooted in producer control and consumer gullibility.”

Advertisements for electropathic belts began to decline around 1910 and organizations like the American Medical Association started to more vigorously prosecute unlicensed medical sellers. A number of newspapers and magazines—such as Science Siftings, which would eventually become Science—started regular exposé columns that commentated on patent medicines and foods.

“The role of consumers in the fortunes of lesser known electrotherapy companies is harder to document,” Loeb wrote. “But it can be said that the remaining commercial electrotherapists found themselves functioning in a markedly changed commercial milieu.”

Object of Intrigue is a weekly column in which we investigate the story behind a curious item. Is there an object you want to see covered? Email ella@atlasobscura.com.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook