The Strange History of Royals Testing Food for Poison With Unicorn Horn

It was actually narwhal tusk.

Pity the unicorn. Though mythical, the beast can’t seem to catch a break. Whether portrayed in medieval bestiaries or Harry Potter, they are constantly chased by dogs, trapped, or killed for their horns. According to ancient scholars such as the Greek physician Ctesias, the horns’ magical properties included purifying water and banishing poison in food.

Luminaries from Aristotle to Leonardo da Vinci believed unicorns to be real, and physicians in the Middle Ages began claiming the purity of unicorn horns could detect poison. That claim made unicorn horns a popular item among the royal and rich. Accounts abound of European nobility using horns to puzzle out if their food was fatal.

But how do you get a unicorn horn in a world without unicorns?

Sometimes, the answer was rhino or walrus horn. But the most common item taken by royals as unicorn horns was what is now considered one of the most expensive materials in all history: narwhal tusks. Narwhals are small whales with Arctic swimming grounds, and their single ivory tooth can reach nine feet in length and swirl, tapering, to a point. Long hunted by the Canadian and Greenland Inuit for food, they were also hunted by another group: Vikings. When they roamed the seas in the early Middle Ages, Vikings hunted and harvested narwhal horns, which they sold without revealing their origin. These horns became so emblematic that by the 12th century, the twisted shape of the narwhal tusk became the accepted image of the unicorn horn.

Their potential mystical powers made them rare nearly beyond price. In his paper A Goblet of Unicorn Horn, art historian Guido Schoenberger commented that “among the things sought by man to protect life and prevent death, none was more highly regarded than the horn of the unicorn.”

Pure-white unicorns were a potent symbol. Often, their purification powers were attributed to a holy connection to Christianity and Jesus Christ. Other times, they signaled courtly love. But neither of these high-minded associations kept royalty from buying horns that necessarily came from dead unicorns. Lorenzo de Medici owned a narwhal tusk that was worth 6,000 gold coins, while Queen Elizabeth I reportedly received one worth £10,000 (the price of an entire castle). Danish rulers were once crowned on a throne made of “unicorn” horns—the royal chair is still visible at Rosenborg Castle in Copenhagen.

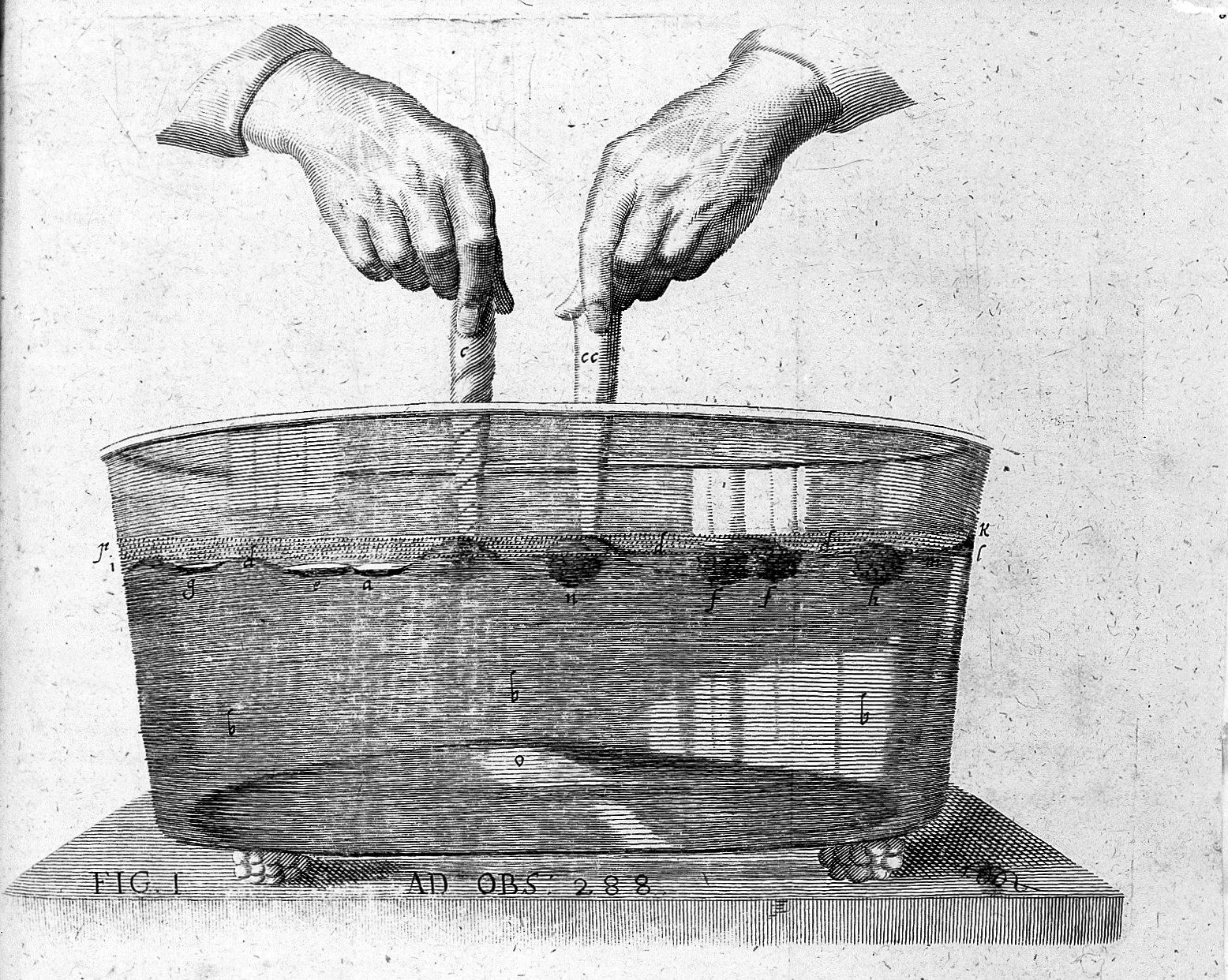

There were many uses of not-actually-unicorn horn. Powdered narwhal tusk was sprinkled on wounds and swallowed to cure disease. But it was most often used to detect poison. Chunks of tusk were turned into goblets, knife handles, and amulets to be worn around the throat, while even tinier pieces were used to test food and wine. Poison was present if the ivory changed color or started to sweat. The complete lack of successfully discovered poison didn’t discourage the horn trade.

For the backstabbing nobility of the late medieval era and the Renaissance, poisoning seemed all too likely. While most royals likely died of natural ailments, the undetectability of poison in the years before modern medicine created healthy suspicion among those with many enemies. The vindictive Medicis were big fans of unicorn horn, and Mary, Queen of Scots, wanted it to test her food while held captive by her cousin, Elizabeth I. But in addition to the unicorn horn, royalty usually had a person try their food as well, which was probably much more effective.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook