19th-Century Museums Swapped Priceless Artifacts Like Trading Cards

Victorian curators filled holes in their collections by exchanging “dupes.”

In 1896, New York City’s American Museum of Natural History hired Franz Boas, a notable anthropologist and curator, to spruce up its growing-but-inadequate collection of ethnographic materials. At the time, the institution boasted numerous Native American artifacts, but had a limited collection of similar objects from around the world. Boas, now considered the founder of American anthropology, jumped at the opportunity to curate specific and well-defined collections that effectively captured the complicated global history of human development.

Boas was uniquely qualified to achieve this goal. Having already served in similar roles at Chicago’s Field Museum and Berlin’s Royal Museum for Ethnology, he understood the cardinal rule of late-19th century curation: What you couldn’t get in the field, you traded for. It’s not surprising, then, that when he set out to assemble materials from Indigenous Australians in April 1899, he reached out to Roger Etheridge, curator at the Australian Museum in Sydney, looking to strike a deal.

That month, he wrote to the museum requesting carefully curated artifacts from a single but non-specified group of Aboriginal people. His opening move in these negotiations would have fit right in a century later amid a front-porch trading card swap: he offered Etheridge his dupes. “Our museum is very strong in collections from the Pacific coast of America and from arctic America,” Boas wrote, “and it would be possible to arrange a good typical collection from either or both regions for purposes of exchange.”

Etheridge initially rejected the offer. While his institution owned several of the weapons and tools Boas desired, he could not relinquish them “for the want of duplicates.” Still, Etheridge hoped the museums could come to different terms. “If your Museum is desirous of Marsupial skins,” he responded in May, “a fairly good set, either mounted or in skin, could be sent in exchange for the works of the American Aborigines.”

From a 21st-century vantage, it’s hard to fathom prominent museums swapping stone axes and kangaroo skins as if they were Pokémon; however, according to Catherine Nichols, a lecturer in cultural anthropology and museum studies at Loyola University Chicago, this exchange between Boas and Etheridge perfectly encapsulates the common practice in their era of swapping duplicates—items Nichols defines as “a kind-of-thing” of which a museum already owned enough representative examples “to serve scientific and educational purposes.” Museums usually considered a “kind of thing” a specific item from a distinct region, species, or people—a Zuni vase for instance, or a Zande spear-head. If a museum owned enough examples of one of these vases or spears, it labeled excess artifacts as duplicates.“Almost all museums exchanged duplicates in the late-19th and early-20th centuries,” Nichols says. “Every exchange was different to a point, but people were often trying to fill gaps in their collections. So, if an institution didn’t have specific material, and it knew a different museum did, it would write and ask about duplicates.”

According to Nichols—who unearthed many of the exchanges detailed in this article amid her extensive research on the subject—19th-century museums saw nothing unethical in this behavior. Most ethnographic items were originally procured either through bartering directly with indigenous peoples or through funded excavations. Curators like Boas and Etheridge believed the transparent nature of these methods cleared them of any ethical grey area, even when exchanging culturally sensitive items.

Indeed, examples of these exchanges abound in the records kept by most major museums. Curators from across the world often reached out to one another with wish lists, alongside inventories of surplus items available for one-off trades. Some even established decades-long trading relationships, thereby creating a global network that saw the exchange of countless artifacts, ranging from contemporary animal specimens to the skulls of ancient Romans.

According to Nichols, this network effectively established duplicates as a world-wide currency among anthropologists, zoologists, and archaeologists. Its existence caused museums of the era to expand purchase and expedition efforts to include the procuration of excess artifacts they could swap for items on lists often referred to as “desiderata.” For example, says Nichols, “if a museum was going to send an expedition to the Philippines, it would collect more than it ultimately needed, because it knew that if it collected multiple examples of something, it could trade them.”

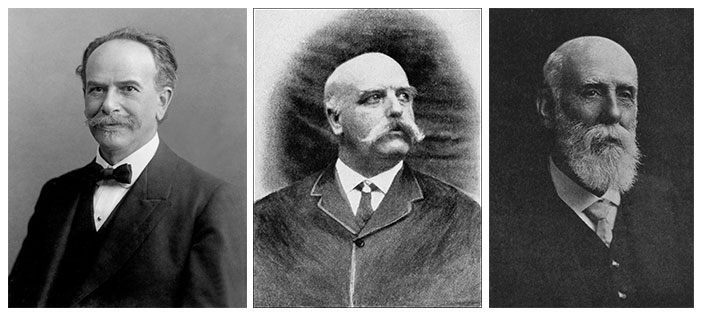

Like any collectors’ market, the museum exchange network required successful participants to strike a careful balance between trustworthiness, aggressiveness, and collegiality. Few did this better than Enrico Giglioli, director of the Royal Zoological Museum in Florence between 1874 and 1909. Giglioli, who also served as vice president of the Italian Anthropological Society, traded with nearly every major museum in the western world. According to Nichols, records of his exchanges with other curators now provide anthropologists great insight into the back-and-forth nature of large scale exchanges.

“Giglioli was super persistent in terms of trying to assemble the kind of collection he wanted,” she says. “He would keep coming back until he got exactly what he wanted, and he would use whatever means he could.” Though Giglioli conducted trades that ran the scientific gamut, by the late-19th century, he was largely fixated on a single passion project—a comparative analysis exhibit, which demonstrated the centuries-long evolution of tools used by indigenous peoples in isolated parts of the world. When negotiating with museums for unrelated swaps of animal or plant specimens, he often serviced this project by requesting rare items like stone axes, bone needles, and ice chisels.

In 1889, for example, Giglioli sent the Smithsonian Institute a desiderata list that included nearly 50 items from the indigenous peoples of Alaska, California, and the Midwestern plains of the United States. Expecting the museum to offer only duplicates, he prioritized obtaining modern examples of axes, flint knives, and arrowheads—though, as he added in an attached letter, “any of the ancient types of Indian stone implements [would also] be most welcome.”

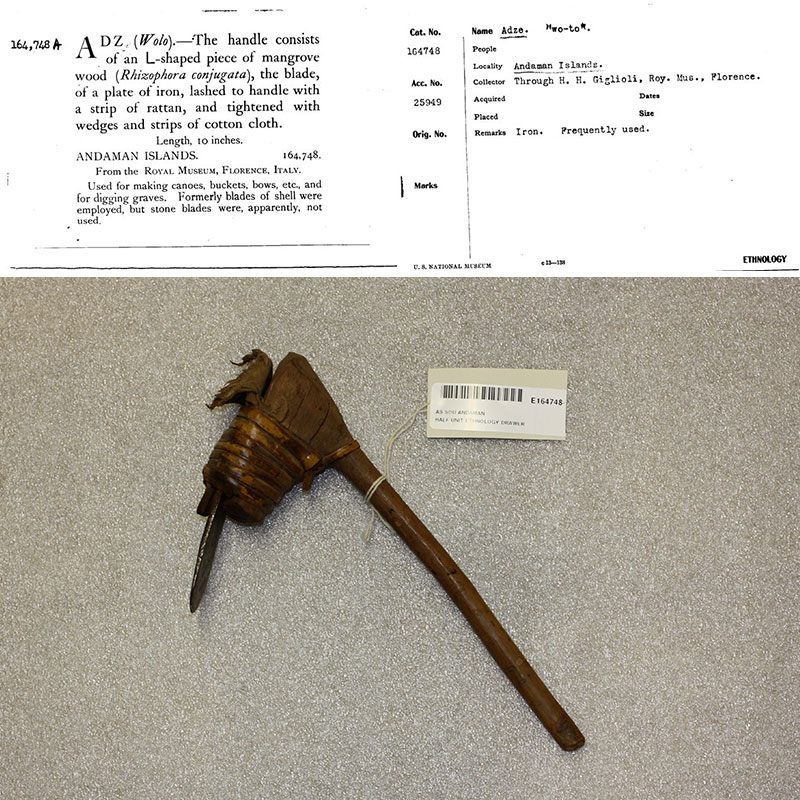

In return, Giglioli initially offered ethnological material from Oceania, a geographical region that includes Melanesia, Micronesia, Polynesia, and Australasia. When this failed to procure what he wanted—specifically rare weapons from the Dakota and Apache tribes—he upped the ante a few years later with a comprehensive set of Andaman artifacts collected by a prominent anthropologist named Edward Horace Man.

Man, then famous for his monograph on the indigenous inhabitants of the Andaman Islands, collected (or arguably took) so many artifacts during expeditions to the region in the 1880s, he seems to have flooded the British museum market. By 1887, for instance, he had sent 753 Andaman artifacts to the Oxford University Museum of Natural History alone. “We already have far too much Andaman and Nicobar things,” an Oxford representative later lamented to one of his peers. “There was in Pitt Rivers one whole gallery full of scarcely anything else. They quite swamped the rest. Now, I hope to reduce their effect by distributing them, but even then there are too many.”

The Smithsonian apparently did not know or did not care about the abundance of Andaman artifacts available on the international market. Giglioli’s offer—which included belts, baskets, canoes, sleeping mats, bows, and just about everything else collected on the island—proved too much to resist for Otis Mason, a Smithsonian curator. “I take pleasure in saying that this our best offer,” he wrote to his colleague, George Brown Goode. “No one has made a more desirable offer of exchange. I should therefore move to give this the very first place and accept the offer at once.”

According to Brian Gill, a former curator at the Auckland Museum in New Zealand and author of The Unburnt Egg: More Stories of a Museum Curator, Giglioli was not alone in his mastery of the exchange economy. He believes the records of Thomas Cheeseman, who served as curator of his museum between 1874 and 1923, are equally impressive, and, in many ways, better illustrate the unique opportunities created by the international trade market. “Auckland Museum had very small budgets during the period and had very limited ability to buy objects from dealers,” he says. “Exchange offered a way around this cash problem and enabled the acquisition of many objects that could be exhibited for the delight and education of the public.”

During Cheeseman’s prolific reign as curator, Gill says, he greatly expanded international holdings in his museum (now known as the Auckland War Memorial Museum), largely through swaps with men like Giglioli. His success, he says, speaks greatly to the two main movers in the exchange economy: scarcity and desirability. Because Cheeseman operated from an isolated region rich in unusual flora and fauna, he easily elicited valuable return on items like kiwi skeletons, stuffed kakapos, and other native specimens. He also had access to Maori ethnographic items, some of which he traded for artifacts as wide-ranging as an Egyptian mummy, ancient Italian crania, and prehistoric axes.

The exchange process mastered by Cheeseman, Giglioli, and countless other curators eventually ran its course. According to Nichols, while natural history museums still occasionally exchange non-man-made items, anthropological trades largely “fizzled out” by the 1960s. As staff turned over at major museums, subsequent generations took a new mindset into the field and beyond. “In the early days,” she says, “there was not a lot of need for fine levels of variation. Now, our techniques and our way of approaching things have become more advanced. Anthropologists have a greater appreciation for the variance of objects that was overlooked when items were designated as duplicates.”

More importantly, she says, ethical concerns have greatly complicated the idea of ownership. Many of the items in modern museums were crafted by tribes with extant descendant populations. To trade such artifacts would not only call into question an institution’s claim to specific items but also the very notion that museums primarily exist to keep, preserve, and display precious material.

Indeed, 1990’s Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act obligates any American museum that receives federal funding to honor requests from native tribes to reclaim culturally important materials. There was a time, Nichols says, when museums feared that this and similar legislation would leave their institutions with empty shelves. This is not the case now, she contends, at least in part thanks to the complicated legacy of curatorial exchanges. Because items have been “coming in and out of museums from the very beginning,” she says, most institutions now recognize that their ownership of culturally sensitive material has always proven tentative and that those making repatriation requests often stand on higher ethical ground.

“Many museums are not only compliant with NAGPRA,” she says, “but they welcome repatriation requests and believe that a lot of good ultimately comes out of these conversations.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook