The Edible History of Confetti

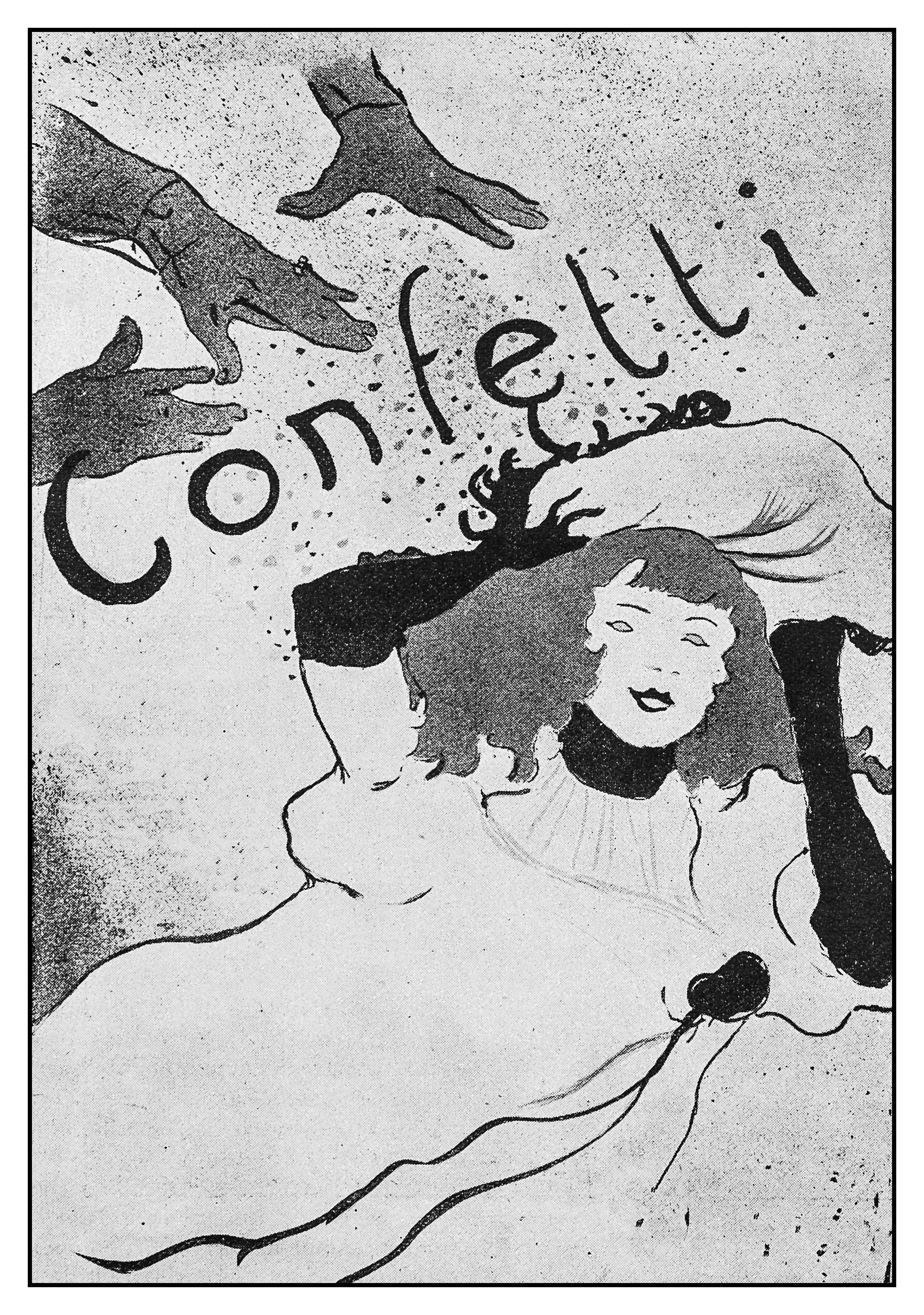

Before the paper variety, nuts, hops, and dates rained down—and put out the occasional eye.

In the late 1820s, William Gunter, an English candy man visiting Italy, observed a tragic accident involving sugared almonds. “They pleasantly pelt each other with these trifles,” he wrote in his Confectioner’s Oracle, describing a festive food fight at Carnival. “But an English country gentleman threw his Comfits with such savagery that he actually put out one of the eyes of his young bride!”

A freak occurrence? Not at all. “Comfit” is an old English term for the sugared pan candy the Italians called confetti. These innocent-looking, snow-white sweets had long been the ammo of choice when it came to hurling edibles at festive celebrations. In terms of velocity, they were the original fast food.

The bits of colored paper that now rain down at sports championships and on New Year’s Eve share the name “confetti,” but it’s been denatured into something floaty and harmless. Why? Because society got fed up with the candied version: the mess, the bruises, the tears, the eye patches.

Humans have always thrilled to a bounty from on high. These were the original windfalls: nuts shaken loose by the wind, gravity-borne apples, olives littering the shade of the tree. The notion that providence bestowed these blessings was epitomized in the gift of manna in the Old Testament: Then said the Lord unto Moses, Behold, I will rain bread from heaven for you; and the people shall go out and gather a certain rate every day (Exodus 16:4).

What began as a natural showering of readily collected food was replicated in community ritual, especially marriage ceremonies. A cascade of foodstuffs was a hint to the newly betrothed: be fruitful and multiply. With their gratifying ballistics and lasting shelf life, nuts were universally popular. Other items, as detailed in 1926 in Edward Westermarck’s A Short History of Marriage, included hops in Slavic countries; shortbread in Northern England; and raisins, figs, and dates in Morocco.

The happy couple was blessed, and so were the pourers, tossers, and hurlers of foodstuff. Before grooms could move on to fertility duties, they had an obligation, as Virgil notes: “Scatter, bridegroom, the nuts.” Young boys loitered outside wedding venues, hoping to score free food in the scramble. This was a form of social insurance: make a show of sharing the wealth, and you keep the masses happy.

It was also a small-scale re-enactment of a grander public ritual, taken to extremes by the Roman Emperor Nero. This was the sparsio, defined as “throwing things among the multitude to be scrambled for in scenes of wild disorder.” In his biography of the emperor, the historian Suetonius recounts gladiatorial games where “many thousand articles of all descriptions were thrown amongst the people to scramble for; such as fowls of different kinds, beasts of burden, wild beasts that had been tamed.” Suetonius, who was a constant critic of Nero, may have exaggerated, but this big-league largesse kept the populace happy and distracted from the leadership’s shortcomings.

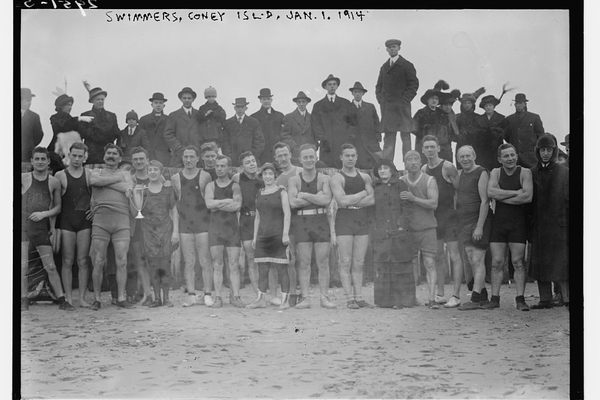

What do scrambles have to do with confetti, either the nutty or the paper variety? All incarnate blessings rained from on high. They could be Imperial-grade decadent, as in ancient Rome, or humanitarian. Gail Halvorsen, an American pilot during the Berlin airlift, received Germany’s highest medal of merit in 1974 for attaching parachutes to candy and dropping it on war-wracked children below.

The candy confetti that William Gunter witnessed in 19th-century Italy can be traced back to when sugar became widely available in Europe in the 1400s. Confectioners began glazing dried fruit, nuts, spices, and seeds.

In Italy, sugared almonds were a particularly prized form of confetti. Their Greek cousin, koufeta, still appears at traditional fetes. The French dragée is a posh, beautifully packaged version. Quite wonderfully, these can be shot sky high thanks to artillery shells made by the munitions department at Braquier, France’s foremost sugared-almond manufactory.

It was at Carnival in 19th-century Italy, during the grand parade of carriages, that lobbing sweetmeats truly went postal. Foreign visitors were agog—Charles Dickens regaled audiences with fevered dispatches from the Corso. A delighted Goethe wrote that “everyone has leave to be as mad and foolish as he likes, and almost everything, except fisticuffs and stabbing, is permissible.”

Sugared-almond confetti were the munition of choice, especially when making love, not war. Tossed ever-so-lightly at an attractive, would-be belle or beaux, they meant “you’re looking fine and I want to get to know you better.”

Alongside the candied nuts came an innovation: ersatz confetti that looked like sugared almonds but was made of plaster of Paris. Protective wire masks became essential Carnival gear. The impact was fierce, all the more so the components, including quicklime. George Stillman Hillard, in his 1854 book Six Months in Rome, reported that “the first sensation is as if the points of a thousand needles had been suddenly shot into the skin; and then a cloud of darkness settles down upon the eyes, which gradually passes off in a rain of tears.”

Paper confetti wafted to the rescue in the 1890s. The advantages of paper were clear: It was a less bruising, more colourful, and less sticky toss, and easier to sweep away. And it put an end to incidents such as the one reported in 1835 in London’s The Penny Magazine: of “little boys and ragamuffins” who dashed to collect confetti, “down on their knees, even crawling among the wheels of the carriages and the horses’ legs to pick up the plums, which they think it is a sin and a shame to waste.”

Strips of paper also had the benefit of hang time. Tissue and foil confetti doesn’t hail, it floats, suspending the effect a few seconds longer. In March 1894, The New York Times rhapsodized, “The confetti made a velvet soft to the feet, picturesque to the eye, and novel even to the most advanced taste.”

Which brings us to confetti’s enduring appeal—no matter what the raw material. It’s about creating a spectacle and a flurry of excitement with one’s own hand.

Whether it’s celebrating a friend’s wedding, capturing beautiful effect on camera, making little kids whoop, or ringing in the New Year, confetti is a sensation for the eyes, and, when of the old-school variety, taste and touch too.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook