Wheatena: The New Jersey Cereal So Popular It Had Its Own Radio Serial

“Mother safeguards against cold and hunger by giving them each a steam-ing bowl of Wheatena as their cereal for breakfast”…a 1914 advertisement for Wheatena. (Photo: Internet Archive/flickr)

A century ago, a delicious, nutty perfume wafted across the east side of Rahway, New Jersey each morning. Commuters would catch a tempting whiff while they waited at the railway station. Children on their way to school would feel their stomachs rumble as the toasty scent filled the air.

“The aroma was just beautiful,” remembers Alex Shipley, the Rahway city historian.

It came from Wheatenaville. The modern factory that produced Wheatena cereal roasted bushels of wheat for up to 10 hours a day, beginning at dawn. Later, that toasted wheat would go into distinctive blue-and-yellow boxes. A staple on American pantry shelves by the 1920s, Wheatena emerged as not just a health food, but as a media phenomenon. Wheatenaville, the Rahway factory complex, transformed into Wheatenaville, the 1930s radio serial about a perfect family in a perfect town that ate Wheatena for strength and prosperity. Judging from the millions of boxes of Wheatena sold in its heyday, most Americans over 70 should remember it well.

But in the 1950s, the tide of pre-sweetened breakfast cereals, as well as the decline in U.S. manufacturing, hit hard. Wheatenaville became a victim of America’s sweet tooth.

Wheatena may have been ahead of its time. Today, millions of health-conscious eaters have adopted the Paleo-ish diet to reclaim the unprocessed dining habits of our ancestors. Food guru Michael Pollan advises consumers to “eat food, not too much, mostly plants” and to abstain from any foods their great-great-grandmothers wouldn’t recognize. Around this time every year, people make resolutions to eat healthier. The same foodies noshing on heirloom veggies and ancient grains today probably would have started their mornings with steaming bowls of hearty, malty, slightly crunchy Wheatena 100 years ago.

Around the time of the Civil War, American breakfasts consisted of pork, bacon and butter. Some religious movements sought healthier, vegetarian options based on grains, “but they were basically inedible,” says Topher Ellis, co-author of The Great American Cereal Book. That changed in the late 1800s with J.H. Kellogg’s Corn Flakes and C.W. Post’s Grape-Nuts—palatable commercial successes that spawned many imitators.

They included George H. Hoyt, a New York baker. He experimented with toasted whole wheat—tastier than oatmeal and corn grits—and sold it by the pound. He called it Wheatena. “Our Wheatena foods are unexcelled for their health-giving, life-sustaining properties,” claimed Hoyt’s newspaper ad in 1879.

A 1910 advertisement for Kellogg’s Corn Flakes. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Wheatena, however, did not immediately transform breakfast. A few years later Hoyt sold his concept to Dr. Frank Fuller, a professional gadabout and president of the Health Food Company. (Fuller later pled guilty under the 1906 Food and Drugs Act for falsely advertising the medicinal benefits of ordinary bread.) Fuller produced Wheatena at a plant in Ohio, and pioneered the practice of selling cereal in boxes instead of barrels. Until Fuller came along, grocers sold cereal by the scoop, and shoppers brought their own empty buckets to transport their purchases home. The practice created ample opportunities for contamination from dust, bugs and dirt.

In 1902, a Health Food Company executive named Arthur Wendell bought the burgeoning business and moved the headquarters to Rahway, on a site next to the railroad linking New York and Philadelphia. The location eased shipping, but it also made his building a local landmark. “As soon as people came in on the railroad, they’d see the Wheatena factory,” says Shipley.

Wendell designed a four-story factory with large windows on each floor for ventilation and light. Inside, “the sunlight plays on the golden grains of selected winter wheat as they are being transformed into the delicious and nourishing whole wheat granules of Wheatena,” a 1925 pamphlet reported. Outside, its water tower shaped like a Wheatena box presided over huge fields of wheat. “It was a gorgeous building, pure white, and landscaped beautifully,” Shipley says.

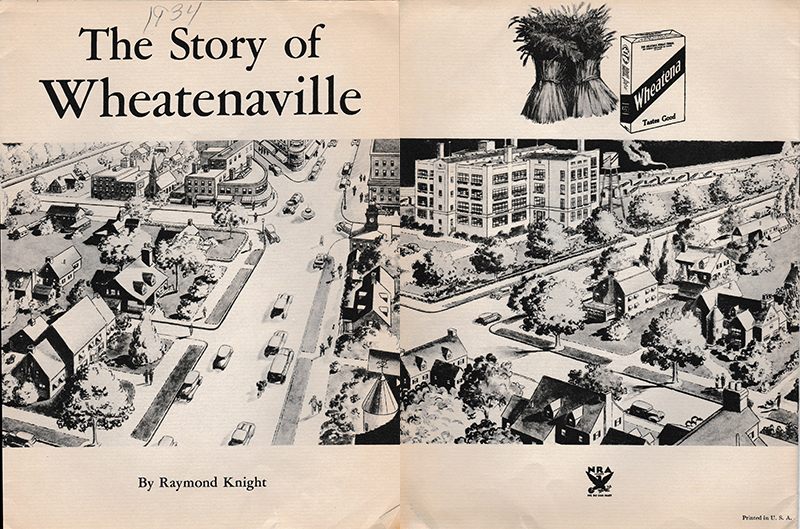

A booklet, which was sent to listeners of the Wheatenaville Sketches radio show upon request. (Photo: Courtesy Kathryn Long)

The factory took on the flavor of a small city, with a staff of 150 bakers and packers. In newspaper ads, the company’s street address read “Wheatenaville, Rahway, N.J.” Soon, Wheatenaville went on the air in a national ad campaign.

“Radio was the cool way to reach out to people,” says Ellis, the cereal expert. In 1932, “Wheatenaville Sketches” debuted on the NBC and Columbia networks, in which the fictitious Batchelor family ate a daily breakfast as “good, wholesome and nourishing” as the show itself. The half-hour episodes showed Billy Batchelor (voiced by actor Raymond Knight), publisher of the Wheatenaville News, battling corruption and helping the poor—messages that resonated with Depression-era audiences.

The show proved so popular that the Wheatena Company actually published two editions of the Wheatenaville News covering Billy’s marriage to his sweetheart and their subsequent baby, Billy Jr.

In 1935 and 1936, the company sponsored episodes of the Popeye radio program for kids, replacing spinach with Wheatena as the sailor’s food of choice. But its days as a leading breakfast cereal were ending.

Wheatena fell from favor in the 1960s, when sugary cereals became more popular. Apple Jacks, pictured here, was launched in 1965. (Photo: Kris Millerflickr)

After the first pre-sweetened cereal came on the market in 1939, many cereal companies began featuring cartoon characters on their boxes, adding sugar and food coloring to the products, and running ads during Saturday morning TV to entice kids. American consumers lost interest in Wheatena’s old-fashioned wholesomeness.

Wheatenaville, the factory, closed in 1965, and a series of companies bought and sold the brand. The state-of-the-art facility in Rahway became a warehouse for a book publisher. After 1975, it stood vacant as plans to renovate the reinforced concrete structure fell through. This summer, the city began to demolish its former fortress of farina. Today, HomeStat Foods of Dublin, Ohio, is its proud manufacturer. The only memorial to the cereal’s place in Rahway history is a small green expanse opposite the factory site—Wheatena Park.

But, says Shipley, “there’s a possibility of putting a marker up.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook