When Disaster Strikes, Museums Call In The A-Team

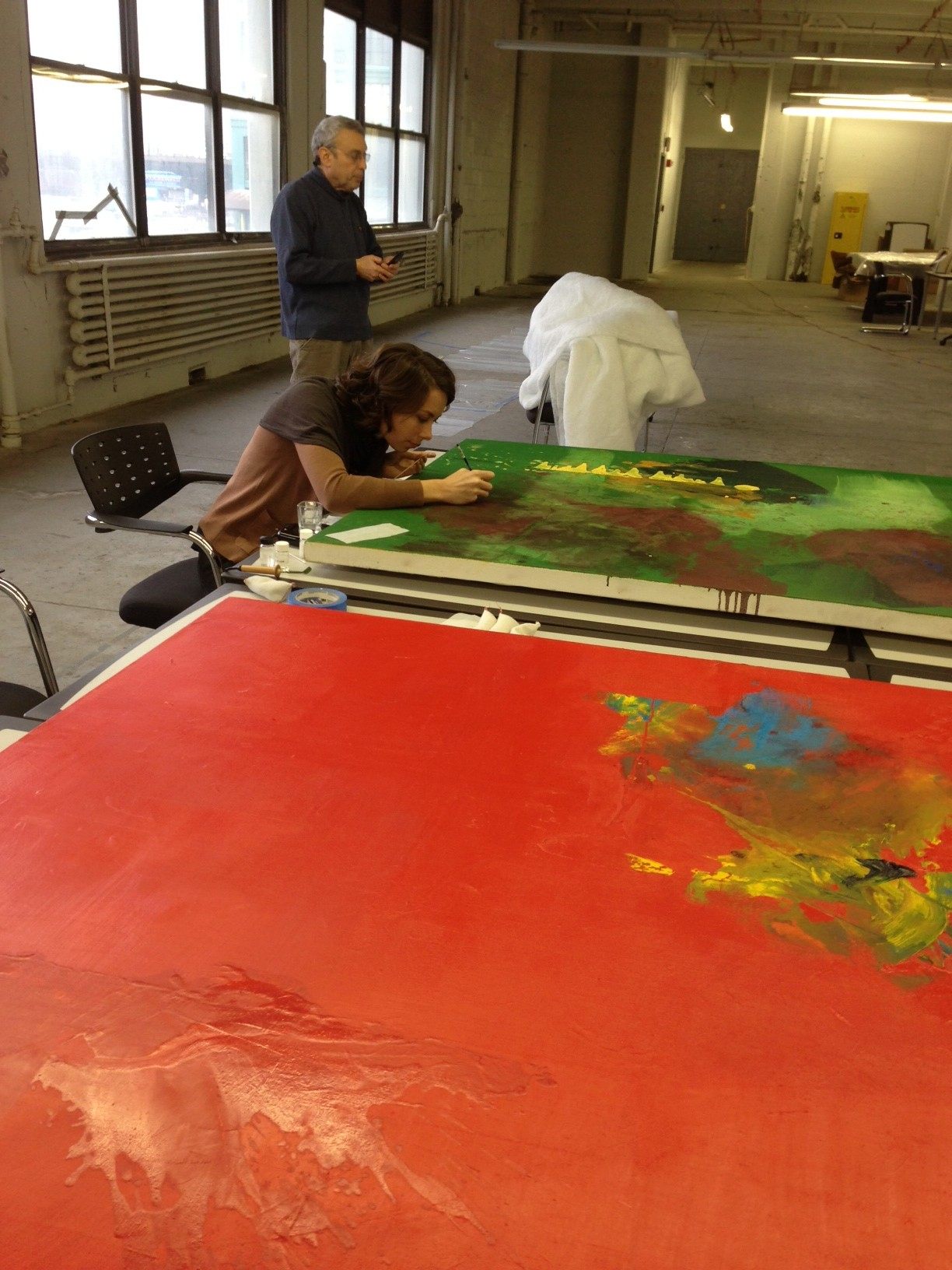

Restoring a painting at the FAIC Cultural Recovery Center in Brooklyn. (Photo: Courtesy Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works)

Restoring a painting at the FAIC Cultural Recovery Center in Brooklyn. (Photo: Courtesy Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works)

You’ve got a muddy 18th century chest of drawers. Who you gonna call?

The American Institute for Conservation Collections Emergency Response Team, also known as AIC-CERT.

Okay, it’s not quite as catchy as Ghostbusters. But for workers at cultural institutions, the AIC-CERT is a disaster relief A-Team, solving problems ranging from a a burst pipe to a tsunami. They can be the difference between saving a collection or losing millions of dollars and priceless cultural history.

The AIC-CERT team was born out of an informal effort organized to help museums, libraries, archives and historic sites on the Gulf Coast in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, whose 10th anniversary is this year. Teams of volunteers were spending weeks at a time helping organizations assess damage and salvage collections. Afterwards, the Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation (FAIC), a national organization devoted to the preservation of cultural materials based in Washington D.C., decided to convene an official emergency response unit. In 2007 they trained an initial team of 63 people, adding another 42 members in 2011. There are conservators, archivists, curators and architects among their ranks with specialties ranging from care of furniture to paintings. The teams are distributed throughout the country, and can be reached by a 24-hour hotline. They often work in a supervisory role, providing advice over the phone or by email, but also respond on the ground. Funded through donations and grants, their services are free. AIC-CERT crews have assisted in the aftermath of the Haiti earthquake, Hurricane Ike, and the Minot, ND floods.

One of the major issues faced by the FAIC Cultural Recovery Center is paintings with mold. (Photo: Susan Duhl/Courtesy Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works)

One of the major issues faced by the FAIC Cultural Recovery Center is paintings with mold. (Photo: Susan Duhl/Courtesy Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works)

After Superstorm Sandy swept through New York, they established a temporary cultural recovery center in Brooklyn where teams of volunteers cared for over 3,000 works of art, many from individual artists whose studios and storage areas were flooded.

“Whatever happened to your building probably happened to your home,” says Eric Pourchot, who is director of institutional advancement for the FAIC and managed the Sandy response. “So it’s affecting your workers, your family. The grocery store might not have power, you’re looking for what you can eat that night.

“It’s really helpful to have outside eyes come in and say everything is going to be OK.”

The Wake-Up Call

The AIC-CERT is part of a revitalized effort to get cultural institutions to prepare for the worst. There are catastrophic scenarios: hurricanes, earthquakes, building collapse, chemical spills. But much more common are a laundry list of mundane—but also potentially cataclysmic—cases that include burst pipes, broken windows, pest infestations, and faulty heating and air conditioning systems. But widely reported and devastating natural disasters have helped spur organizations to plan in advance for emergencies.

Katrina was a “wake up call” says Barbara Moore, a 3D object conservator and AIC-CERT member and trainer who advises institutions on how to plan for disasters and teaches disaster response workshops.

“I think it’s become much more real,” says Moore, who has taught workshops at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The National Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian.

While the general public may be drawn to dramatic tales of rescue, Moore and others interviewed for this story stressed that preparedness is key. Getting organizations to assess risk and create a comprehensive disaster plan is the most important step to emerging from a crisis with a collection intact. Taking steps as simple as compiling contact numbers and making connections with state and local officials is just as important as the actual response and recovery . The Ohr O’keefe Museum in Mississippi in Biloxi, MS is often cited as a success story—they transported many holdings to safe ground before Katrina’s flood waters arrived.

Paintings with mold damage being worked on at the FAIC Cultural Recovery Center, which involves removing the painting from the stretchers, cleaning with an alcohol solution, and re-stretching. (Photo: Susan Duhl/Courtesy Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works)

Paintings with mold damage being worked on at the FAIC Cultural Recovery Center, which involves removing the painting from the stretchers, cleaning with an alcohol solution, and re-stretching. (Photo: Susan Duhl/Courtesy Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works)

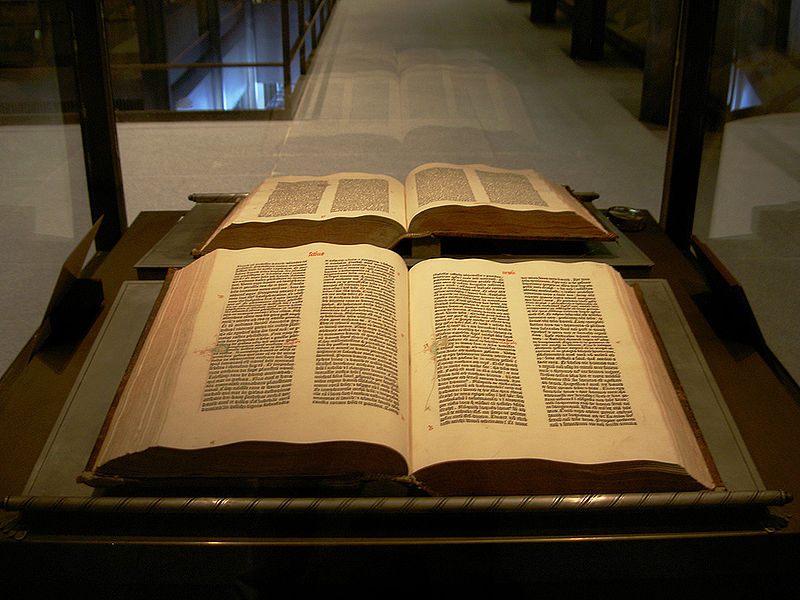

“A lot of disaster planning has more to do with how you would save something after something happens to it, as opposed to imagining yourself running into a building as its filling with water to save the one amazing thing,” says Rebecca Hatcher, preservation coordination librarian for Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Among the amazing things at the library are a Gutenberg bible, medieval and early modern materials, courtroom sketches of the 1971 trial of Black Panthers Bobby Seale and Ericka Huggins, and “Sesame Street” video cassettes.

The Beinecke’s disaster plan provides for a myriad of scenarios, including gunmen and bomb threats. (In the case of all disasters, Hatcher said, the priority is human safety first, “no matter how amazing the collection is.”) The library is prepared to stop water from creeping under doors with small inflatable barriers (“We love them but they’re not actually that exciting”) and sandbags. Because, she says, a disaster of a large scale could quickly overrun the capabilities of the staff, the building is equipped with freezers.

Freezing is a well-loved tactic for those dealing with damaged collections. Particularly for paper materials, freezing can halt damage from advancing, allowing caretakers to deal with it at a later time when more help has been called in. The library also has a contract with a vendor that delivers mobile freezers. In case of fire, the Beinecke is equipped with a gaseous fire suppression system that snuffs them out by lowering the building’s oxygen content, but not so low that humans can’t survive. There is even a popular rumor that the imposing marble and granite building can retract into the ground in the event of, say, an alien attack or apocalypse. (It can’t.)

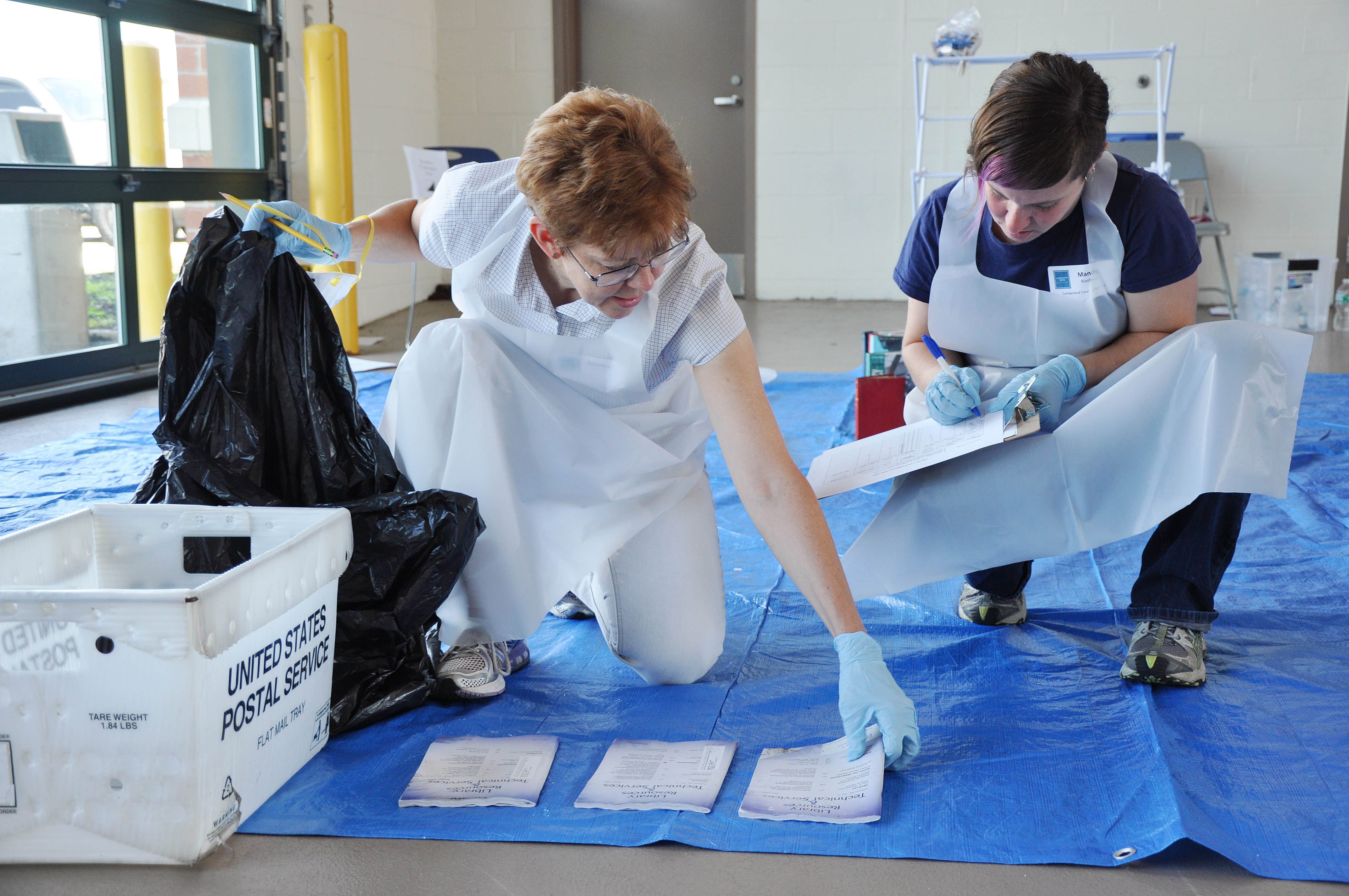

Disposing of water damaged items at the Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts. (Photo: Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts and New Jersey State Archives/Department of State)

Disposing of water damaged items at the Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts. (Photo: Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts and New Jersey State Archives/Department of State)

But high-tech systems aren’t the norm; experts recommend simple steps, such as housing collections in protective cases or even cardboard boxes and keeping them away from windows or sprinkler systems. Dyani Feige, director of preservation services for The Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts, one of the largest nonprofit conservation facilities in the world, says she takes a granular approach, “looking at anything and everything that could impact collections.” She helps organizations assess their risk—is there evidence of past water damage or a tree placed perilously close to a building?—evaluate what items are most vulnerable, and set salvage priorities if disaster strikes, which can be one of the toughest tasks.

People develop such a specific relationship with their holdings that “the idea of choosing among these collections that they are so familiar with and have such connection with can be really, really painful,” she says.

Some prioritize based on which materials will suffer the most if unattended (the oldest, say), are the most expensive or are display anchors, if the institution has exhibits.

We’ve Met the Enemy and It is Water

Here are some things that can happen to collections when they get wet: veneer will lift off the joints of the furniture, books grow mold, iron rusts. Art books, whose shiny pages are coated in clay, will turn into bricks. Ink runs. The skin on taxidermy specimens shrink and their stuffing gets soggy.

Across the board, water and mold were labeled enemy number one. Even when there’s a fire, there’s water. Moore says she doubts there is a “museum on the planet” that hasn’t had to deal with a pipe leak on inventory.

“Most at risk would tend to be organic objects,” says Moore. “Things made out of wood or textile or paper because they respond physically to the water and deteriorate quickest.” Leather, furniture and paintings are also a high priority when water has damaged a collection. Glass and ceramics are less at risk because they are more easily dried out.

A Gutenberg bible on display at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Renée Wolcott is a book conservator at CCAHA and has seen books so soaked with water that they swell and, unable to sit in a straight line any longer, form a soggy arch above the shelf. She has seen a rainbow of mold. In a damp environment, mold can set in with 48 hours and it is one problem that some collections simply can’t recover from; it can devour objects.

Wolcott typically works at the CCAHA tending to rare books and manuscripts—the center is focused on paper objects, including wallpaper, globes and Japanese lanterns—but has occasionally been dispatched to assist in emergency situations. One organization she tended to was located next door to a building that suddenly collapsed. Workman repairing the roof of the cultural institution had to clear out, and no one was allowed back for a couple days.

“And during that time, it poured rain,” says Wolcott. “It bucketed rain.”

The drains clogged, the roof leaked, and water poured onto a collection of historic books. They were deformed and grew mold, they were “really fuzzy.”

Laying out water damaged items to dry at the Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts. (Photo: Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts and New Jersey State Archives/Department of State)

Laying out water damaged items to dry at the Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts. (Photo: Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts and New Jersey State Archives/Department of State)

Mold is bad for books, but it’s also bad for people. Wolcott wore a dust mask and gloves when tending to the fuzzy library. Exposure to mold can cause an allergic reaction and the longer people are exposed to it the more likely it is that people will get sick, experiencing things like sneezing and nausea.

“It’s not pleasant,” says Wolcott.

For that reason, depending on the severity of the outbreak, responders typically wear a range of safety gear, such as masks, plastic suits and booties. Full body suits are popular for cases where there may be rodents, and thus a risk of hantavirus. There are less intuitive risks, too—taxidermy was once treated with arsenic and other poisons to discourage bugs, so unless responders know how a specimen was prepared, a stuffed badger could potentially be toxic and has to be handled as such. Building safety and health risks are all things that have to be evaluated before the mess can be cleaned up.

Once it’s been determined that a structure is safe to enter, responders begin triage.

“Controlling the environment is really crucial,” says Feige, whether it’s re-sealing windows or repairing an HVAC system.

Then caretakers can begin carrying out preliminary conservation measures before more detailed work takes place. Pourchot described books left fanned out on tables and photographs clipped to clotheslines to dry after flooding. If a piece of furniture is wet, you might pull the drawers open to make sure they don’t swell up and break. At the recovery center in Brooklyn, experts removed paintings from their wooden stretchers to check for mold. They cleaned artworks with an arsenal of alcohol, blotting paper and sponges. In many cases, the tools being deployed are simple—it’s just a case of knowing how and when to use them. Don’t freeze an acrylic painting—it will grow brittle and break. Do freeze a book. Teaching workers who aren’t conservators how to do their own cleanup is one of the goals of disaster preparedness champions.

Moore teaches a wet recovery class for organizations in which she fills a kiddy pool with water and submerges items like sweaters, books, photos and artwork that she picks up from thrift shops and yard sales.

“When I’m at a yard sale I buy amateur paintings,” she says, “Which are remarkably resistant to damage. We have a saying, ‘You can’t kill bad art.’”

Participants practice rescuing these cast-offs from the water and learn ways to dry and care for them. (CCAHA offers a similar workshop.)

When confronted with a mangled artifact, an untrained person can grow overwhelmed. “What we find is that people in the midst of disaster will look at something like that and think, ‘Oh my gosh, that’s toast,” she says, “What can I do?’ and even throw things away because they think there’s nothing to be done.”

Moore suggests those individuals take a step back and reevaluate the situation. Because with proper training—and maybe a freezer—not all has to be lost. “It’s quite amazing what can be done to restore things,” Moore says.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook