The DIY Carvings Designed to Deter 17th-Century Witches

Apotropaic marks were simple patterns with a serious purpose: to keep evil and mischief out.

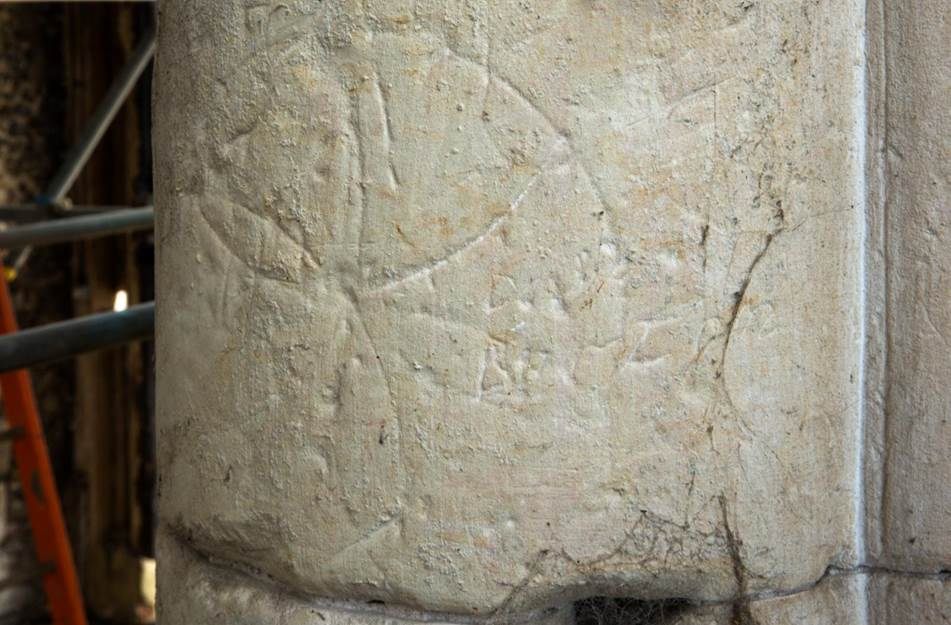

Daisy chain circles and “V” carvings hidden in the nooks and crannies of historic homes and properties across the United Kingdom, once thought to be carpenter’s symbols, hint at Tudor superstition and folklore.

Apotropaic marks, or witches’ marks, have been found in various properties throughout the UK—from Wookey Hole Caves in Somerset, to Shakespeare’s birthplace in Stratford-Upon-Avon, to even the Tower of London. Most of the carvings appear in buildings constructed between the 16th and 18th centuries.

The “apotropaic” terminology comes from the Greek term “apotropaios,” meaning “averting evil.” Witches or their evil conjured spirits were thought to attempt to enter homes via doorways, hearths, and windows, and hide in shadows made by the nooks and crannies of the house. It was believed that once they had entered the property, witches and evil spirits would want to attack the inhabitants, or ruin the most valuable possessions of the owner. Tudor proprietors took a proactive approach to the issue, and carved the apotropaic marks near where items of value were stored.

“Ritual marks were cut, scratched or carved into our ancestors’ homes and churches in the hope of making the world a safer, less hostile place,” said Duncan Wilson, Chief Executive of Historic England, last year. “They were such a common part of everyday life that they were unremarkable and because they are easy to overlook, the recorded evidence we hold about where they appear and what form they take is thin.”

The most popular witches’ mark features a series of intertwining daisies in a wheel design, also known as a hexafoil. The linking design was intended to entice the malevolent spirit and trap them in an infinite loop, thus preventing them from progressing any further into the property. Alternatively, Tudor homeowners would also call upon the supreme divine power of the Virgin Mary for protection, carving Marian symbols such as the letters AM for “Ave Maria,” M for “Mary,” or VV for “Virgin of Virgins.”

Belief in witchcraft dates back to ancient Babylon, and has appeared in texts from the Greeks and Romans. But the conventional stereotype of witches as female figures consorting in dark magic did not emerge until approximately the 15th century in Europe. Before then, in medieval England, folklore concerning good and bad spirits that could affect seasons and running of a household coexisted with the newly introduced religion of Christianity. “White witches,” or “cunning folk” as they were known, were believed to assist in intervening with these spirits for the good of the people, as well as other practices, such as medicine. On counterbalance, it was also believed there were those who would call on their powers for malevolent reasons, such as necromancy.

As Christianity took root in local and countrywide governance, church authorities focused on eradicating pagan beliefs, and the link between the dark magic of demonic conjuring and pacts with the devil, and witchcraft as we know it today, emerged.

Witches’ marks have been found in confined, shadowy areas of properties. Shakespeare’s birthplace in Stratford-Upon-Avon, which later became a pub, had a hexafoil placed where they stored the beer. At Knole House, a Jacobean estate in the southeast English county of Kent, carvings were found on the roof beams and floorboards. The marks were dated using dendrochronology to 1606—only months after the Gunpowder Plot, an assassination attempt by the Catholic Guy Fawkes against the Protestant King James I. During this time, accusations of witchcraft and demonic forces permeated throughout society, and witch trials were rife. The Pendle witch trials of 1612, for example, saw eight women and two men sent to the gallows.

Official legislation against the practice of witchcraft did not start in earnest in the UK until the 16th century, when Henry VIII introduced the Witchcraft Act 1542. In comparison to the rest of Europe, where witch hunts had started as early as the 12th century, the UK was a latecomer to penalizing witchcraft. As religious tensions and social upheaval continued throughout the 1500s and into the 1600s, however, the belief in witchcraft and the subsequent persecutions intensified. In fact, King James I became so interested in witchcraft he wrote a book on the topic, Daemonologie, in 1597. In 1604, he broadened Elizabeth I’s Witchcraft Act to include the penalty of death without the benefit of clergy to anyone found guilty of communing with evil spirits.

The practice of carving apotropaic marks persisted in the last centuries during times of social change, as evidenced by the carving of these symbols into historic buildings in Australia by British settlers in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Given that apotropaic marks were verbally passed down throughout the centuries as folklore and symbols of protection, and were seen as such an everyday feature of households, little has been recorded or researched on the subject.

In an attempt to rectify this, Historic England launched a public appeal on Halloween 2016 to encourage members of the public to search for apotropaic marks in their houses or local historic buildings. The results were overwhelming, with hundreds of new submissions sent.

Soon Historic England hopes to release a report detailing the most surprising examples from their 2016 appeal, and with more records it is hoped more information can be unearthed on these enigmatic symbols.

“Witches’ marks are a physical reminder of how our ancestors saw the world,” said Historic England’s Duncan Wilson last year. “They really fire the imagination and can teach us about previously held beliefs and common rituals.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook