How a Beer Historian Is Documenting COVID-19’s Impact on Brewing

The biggest blow to beer since Prohibition.

This year is the 100th anniversary of America going dry. In 1920, some 1,300 breweries in the United States faced the onset of nationwide Prohibition—a ban on alcohol sales that many expected to be repealed quickly, but instead lasted until 1933. When it ended, less than a quarter of those breweries remained in operation, and, although new brewers opened up shop, many of the survivors failed in the following years, while the rest were absorbed by major manufacturers like Anheuser-Busch. Not until 2016 did the number of breweries in the U.S. top 1873’s record of 4,131.

Today, the coronavirus is exacting the largest impact on American beer since Prohibition, and the pandemic will similarly shape this country’s beer story—an insight that is guiding Smithsonian curator and beer historian Theresa McCulla, who is already working to document this pivotal moment.

By March 23, McCulla, who curates the American Brewing History Initiative at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, had put out a call via Twitter. Like her fellow curators, who are asking Americans to donate grocery lists, letters from patients, homemade masks, and other signs of the pandemic’s effects on everyday life, she asked brewers, bar managers, and beer fans to save material that captures what the beer industry is experiencing: packaging and labels like Hackensack Brewing Co.’s limited-edition quarantine cans, menus geared toward delivery and curbside pickup, hand sanitizer and other alternative products made by breweries, and business records. McCulla is also recording oral histories.

In short, McCulla is gathering the sort of artifacts and documentation she has used to study Prohibition so that she can do the same with the pandemic.

While it’s impossible to predict how COVID-19 will change the beer industry, she is already thinking about the story these objects may one day tell at the Smithsonian. “The means to protect ourselves [from the virus] is to withdraw, in terms of gathering in person,” McCulla muses. “The way craft beer has grown in the last couple of decades is to emphasize the importance of people gathering in taprooms.” Breweries can make and sell beer, but on-premise consumption is a huge chunk of their revenue.

The effect of losing those sales can already be seen: In April, a Brewers Association survey of small breweries found that a combined 58 percent said they would have to permanently close if social-distancing measures remained equally strict for anywhere from one week to three months. The same survey found that 66 percent of brewery employees had been laid off or furloughed.

As breweries attempt to make up lost revenue, regulations formed during Prohibition’s repeal often dictate whether they can deliver beer, ship it, and sell it across state lines.

“The federal government left it up to states to decide how to repeal the Prohibition,” McCulla explains. “That’s why, to this day, you can go somewhere like Las Vegas and buy alcohol 24/7, 365 days a year, but in other places, you may not be able to buy alcohol on Sundays.” A huge hurdle of the lockdown is that in addition to coming up with ways to boost sales, breweries often have to lobby local governments to be able to act on those plans.

Bart Watson, the Chief Economist for the Brewers Association, doesn’t think the pandemic will shape regulations as dramatically as Prohibition, but he does believe changes different states are making could stick around in some form. “We’re already seeing a shift in the short-term regulatory environment, with greater freedoms for breweries and off-premise operators for things like delivery and to-go,” says Watson. “It has the potential to set in motion a wave of different legislative structures because of the need for direct-market access for small producers.”

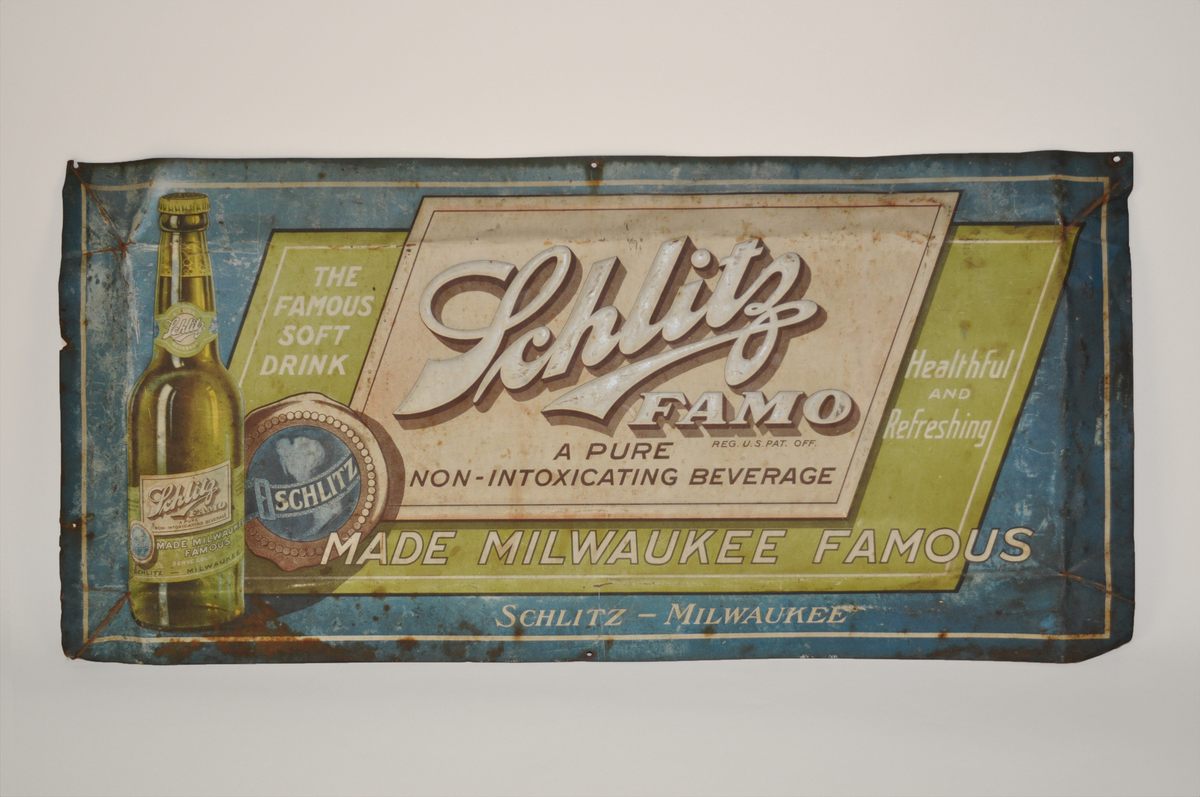

During Prohibition, breweries including Coors, Yuengling, Anheuser-Busch, and Pabst Brewing Company pivoted to make near-beer, soft drinks, infant formula, frozen eggs, ice cream, and ceramics. Many survived by leasing their spaces to other companies and industries—surviving on real-estate holdings that small, independent brewers lacked.

But McCulla is heartened by the increased support that exists for the craft industry now, and the inspiring creativity on display. In New Orleans, Urban South Brewery won a bid to make 50,000 bottles for the state’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness—it is one of many breweries and distilleries making hand sanitizer. In Milwaukee, Good City Brewing took over a vacant bank for drive-thru sales. “It’s been an absolute joy to watch our team roll up their sleeves, adapt, and execute a completely new business model,” says co-founder David Dupee. In San Francisco, Anchor Brewing Company partnered with Bay Area artist Jeremy Fish to post a version of the San Francisco flag on boarded-up restaurants and bars with a QR code that directs people to donate to the United States Bartenders Guild. In Brooklyn, Threes Brewing has taken its eclectic events lineup online and created an online store and its own delivery system.

A bottle of hand sanitizer from Urban South, a photo of Good City’s drive-thru, an art print from Anchor: These are the kinds of items McCulla will collect over the following months and years to tell the story of the pandemic and beer. As she does, she will have to determine which objects best tell that story and preserve our experiences. “That’s the great challenge and art of being a curator,” says McCulla, “trying to judge what those items are and how we can take care of them.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook