The Strange, Smelly Chores That Keep Natural History Museums Running

Even during a pandemic, someone’s gotta feed the flesh-eating beetles.

A few weeks ago, Adam Ferguson entered an enormous walk-in freezer—one-and-half times the size of his bedroom—at the Field Museum in Chicago, where he works as the collections manager for mammals. A crowd of animal carcasses never smells great—under the best conditions, it “smells like skunk and freezer-burned meat,” he says. But in an adjacent part of the lab, where the team stores big bins holding bones waiting for preparators, he got a whiff of something unusually funky. The space reeked of “rancid fat and water with a little bit of ammonia,” he recalls. “Pretty ripe. That’s how I knew there was a problem.” The giant Tupperware holding South American tapir remains had sprung a tiny leak, not much bigger than a pinhole.

The tapir bones rest in a solution of diluted ammonium hydroxide, which pulls out marrow and fat and arrests bacterial growth. They are not far from the remains of okapi and goats that are wrapped in tarps, as well as squirrels, bats, and rodents that sit in containers on shelves. In this case, a little bit of the malodorous, milky-white fluid from the tapir’s bin had trickled out and pooled on the floor. Ferguson cleaned it up and went on his way. It wasn’t a crisis, but it was a good reminder: Museums are dynamic environments, and staff members are always doing their damnedest to fend off entropy.

Even though many natural history institutions are closed to the public due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and most of their staff are hunkering down at home, some museum employees continue to make periodic rounds through their collections. “What museums are doing is stuff that’s about trying to limit the agents of deterioration,” says Jack Ashby, trustee of the Natural Sciences Collections Association, which supports natural history collections across the United Kingdom, and the manager of the University Museum of Zoology in Cambridge. Those agents can be anything from water gushing in from a leaky ceiling to dust to pests introduced from the outside world or escaped from another part of the museum.

The task of deciding whose duties live under that umbrella tends to fall to people pretty high up on an institution’s food chain. At the Field Museum, that power rests with the executive team, says Ray DeThorne, the chief marketing officer; anyone trying to enter the building must flash a letter signed by a museum executive, saying that they have permission to step inside. (In an effort to enforce social distancing, the city has restricted access to the roads around the museum, which lead to the tantalizing shores of Lake Michigan.) The Field Museum has 480 employees and currently averages around 20 people in the building each day, DeThorne says. “We want a minimal number of people in the institution, and have two things we’re concerned about: The health and safety of employees, and the safety of our 40 million specimens and artifacts,” he says. At the Museum of London, most employees seeking access need sign-off from a department head and the security team, and must make arrangements in advance.

The crews keeping these institutions running typically include security workers, housekeeping, and building maintenance staff. They also include less-obvious characters, such as curators, collections managers, and social media managers, whose tasks include feeding beetles; pouring formaldehyde; refilling 230-liter tanks of nitrogen in cryogenic tissue storage facilities; and, in the case of the Field Museum, dressing up like a dinosaur.

Many natural history museums that still collect recently deceased animals enlist some little creepy-crawly “workers” to help out with the dirty work. Colonies of flesh-eating beetles, also known as dermestids, often help clean the bones—and even in a pandemic, insects gotta eat. Ella Haigler, a museum specialist and Osteo Prep Lab manager at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s Museum Support Center, currently goes into the office in Suitland, Maryland, to check on the dermestid beetle colony and take care of other tasks about twice a week. The Smithsonian’s several thousand beetles live in darkness, scuttling around tanks and aquariums that sit in two nine-by-nine-foot converted freezers. Right now, they’re chowing down on the muscles and connective tissues of small birds, a sea turtle, and an elephant. (Active, voracious colonies can tear through small specimens in a few hours, and spend days or months working on larger ones.)

Flesh-eating beetles are picky about their living conditions, which they prefer to be balmy and steamy. The Smithsonian’s beetles are stored between 81 and 85 degrees Fahrenheit, around 70 percent humidity. If the temperature in their tanks drops below 60 degrees Fahrenheit, they’ll refuse to eat; severe cold snaps can wipe colonies out entirely. Once they hoover up all the food on offer, the beetles stop reproducing, and larvae may go cannibalistic by devouring pupae. After a bloodbath like that, it can take months to get a colony up and running again—and museums depend on beetles across the stages of their life cycle, says the Field Museum’s Ferguson, who also checks on his team’s beetle colonies during his weekly rounds. The larvae, for instance, are the best bets for de-fleshing a house mouse, or the little limb bones of a shrew. Haigler keeps them busy (and keeps the peace) with frequent feasts, and if the specimen is desiccated or freezer-burned, she adds, she’ll soak it in such appetizing substances as fish oil.

What goes in must come out: Staff members also clean the frass, or insect excrement, from the tanks, and spritz the hard-working residents with a spray bottle of water. “You can tell they need the moisture,” Ferguson says. “They come out, like, ‘All right! A sprinkler in the summer.’” Anyone tending to dermestid colonies has to be cautious to check themselves for stowaways before they visit other parts of the museum, says Ashby, of the University Museum of Zoology: Rogue beetles that escape their tanks and gorge on collections “can take all the fur off of taxidermy,” Ashby says. He describes the beetles as some museums’ “worst enemy and their trusted employee.”

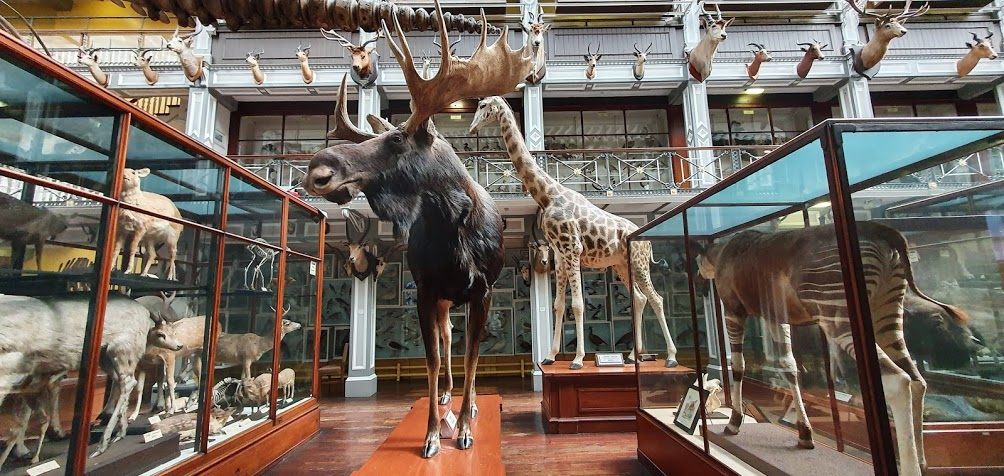

As they wander through galleries, offices, and storage spaces, curators and collections managers also keep an eye out for other pests. Fergsuon scours each floor where the mammals department has specimens, either on view or in prep labs. Paolo Viscardi, chair of the Natural Sciences Collections Association and zoology curator at the National Museum of Ireland’s Dead Zoo, has been checking on the collections weekly, and scans windowsills and sticky traps for evidence of unwanted creatures. As part of their pest management protocols, many museums place traps, such as the charmingly named “blunder traps,” to spot insects that scutter past displays. Viscardi also finds himself swatting and squashing webbing clothes moths with his bare hands. “When they’re flying around, you just hit them,” he says.

In natural history museums, the moths are “a perennial problem,” Viscardi says. They’re especially keen on taxidermy collections, with their appetizing fur and feathers, and also like to wedge themselves between the joints of crustaceans, where there’s sometimes a bit of dried meat. “We have 2 million specimens, and every single one of them is a small banquet for pests, except for the geology,” Viscardi says. When a pandemic isn’t raging, one tactic would be to freeze any affected specimens, because the cold temperatures kill the pests—but that’s not feasible at the moment, because the museum’s freezers are located in other parts of the city. It’s too complicated to coordinate transporting the objects under social distancing rules.

Those rounds are also a good chance to check on humidity levels throughout the galleries and storage areas. Too much humidity can encourage mold to grow, and also makes shrouds of dust sticky, attractive to pests, and difficult to remove. Dips and spikes in temperature and humidity can also cause objects to crack.

Many museums use sensors to monitor these types of fluctuations, but those sometimes require in-person maintenance, too. Every two weeks, Ferguson must change the paper reel in the Field Museum’s hygrothermograph, a machine that monitors a storage room for tanned deer and pig skins, which is kept at 50 percent humidity and 50 degrees Fahrenheit. (Researchers use the skins to extract samples of DNA, pathogens, and more.) Andy Holbrook, collection care manager at the Museum of London, is hunkered down in the countryside and hasn’t been to the museum in more than eight weeks, but colleagues who live within walking or cycling distance have suited up in personal protective equipment and popped over to air-conditioned galleries to change the batteries in temperature sensors. That task was “fairly quick, straightforward, and low-risk,” he says.

Even well-preserved specimens need check-ups. “A lot of people think [museum] collections are pretty stable—you stick it in a jar and it’s okay forever,” Ashby says. “They aren’t.” Specimens suspended in fluid require a once-over, in case alcohol evaporates through old seals, Ashby says. Viscardi is busy with top-ups and other interventions, including rehydrating a withered frog. Without visitors milling around the hallways, he can bring the supplies right to the dead creatures in need. “You don’t want to be mucking around with a trolley full of alcohol or formalin when the public are in the building,” he says.

With visitors likely to be turned away for a while longer, many museums are also working to remind them about all the cool stuff inside—keeping them interested in the collection now, and hopefully nudging them to visit in person when it’s safe to do so. In service of delighting armchair explorers with shtick, the Field Museum’s social media manager, Katharine Uhrich, got special dispensation from the executives to duck into the museum back in March. She and her husband, Steve, donned an inflatable T. rex suit and stampeded around the empty galleries, in character as SUE, the museum’s star murderbird. In one iPhone video they filmed, SUE battles vending machines; in another, the dinosaur saunters around the Hall of Birds and waves to the taxidermy penguins. The videos are gloriously goofy, and loaded with substantive information the science of dinosaurs: The vending machine video, for instance, was a chance to talk about SUE’s foot-long teeth; the bird jaunt was a reminder that the dinosaurs known as theropods included T. rex, velociraptors, and the ancestors of modern birds. Uhrich and Steve made two visits to the museum and recorded more than eight videos, which have been watched more than 1.6 million times in total.

This strange time has helped museum employees be flexible and creative, says Viscardi, of the National Museum of Ireland. Museums hold practice drills for all sorts of emergencies, from terrorist attacks to floods. Viscardi’s team hadn’t prepped for a pandemic, exactly, but they had broader preparedness training last year. “It prepared us to rapidly change our practices and deal with emergent situations as they happen—not get caught up in, ‘This isn’t how we do things,’” he says. For now, beyond his in-person checks, Viscardi is working remotely, catching up on writing and research that had been simmering on the back burner. While museums are closed to visitors, curators and conservators are tucking into tasks that they have been meaning to do for years, while they also make sure the collections will be ready to greet the crowds that eventually return. This is “one of the few times people have had to actually take a breath,” he says.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook