Behind The Custom-Tailored Ritual That Has Powered Congress Since 1774

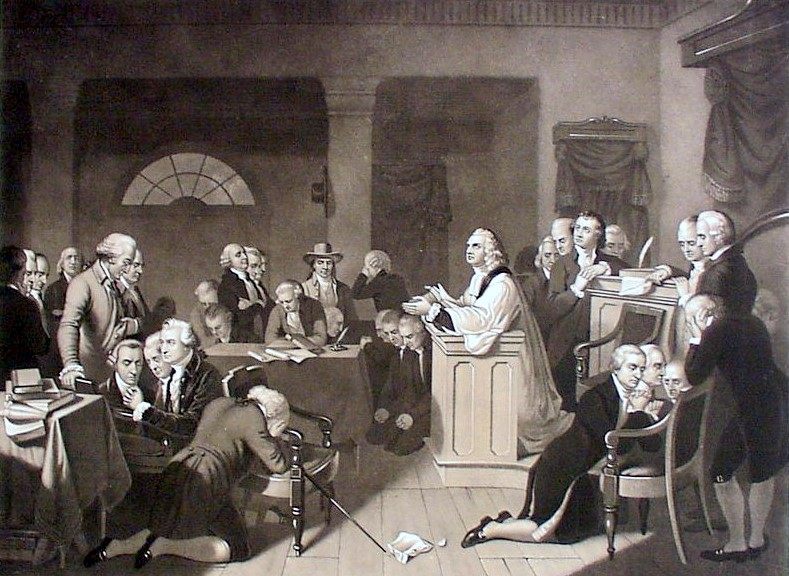

T.H. Matheson’s rendition of “The First Prayer in Congress,” given by Reverend Jacob Duché at the First Constitutional Convention in 1744. (Image: Josve05a/WikiCommons Public Domain)

It’s a typical day on Capitol Hill. President Obama asked for $3 billion dollars to fight the Zika virus. The Senate is arguing about the Affordable Care Act. The House held a pro forma session, gathering briefly in order to agree to reconvene tomorrow.

But before any of that–unseen by all but their in-person audience and the most devout C-SPAN watchers–the House and Senate each kicked things off with the legislative branch’s daily aperitif: a one-minute prayer.

Senate Chaplain Barry Black asked God to “use our lawmakers today as ambassadors of reconciliation and renewal.” Guest Chaplain Reverend George Schommer prayed, on behalf of the House of Representatives, for “the wisdom and understanding of all law: natural, human, and divine.” Each prayer was recorded in the Congressional Record, where they joined thousands of other daily distillations of national feeling and concern.

Along with the ingredients you’d expect from prayer– gratitude, invocations of a higher power, requests for strength and guidance–they also illuminate the twists and turns of America’s history. Anyone who listened only to these prayers would get a piquant and evocative snapshot of what the country is worrying about at any given time.

ZeBarney T. Phillips opens Congress in 1939. (Photo: U.S. Senate/WikiCommons Public Domain)

As legal scholar Christopher C. Lund relates in “The Congressional Chaplaincies,” a 2009 overview of the tradition, the chaplaincies have “a remarkable–and a remarkably checkered–history.” American legislative prayer is older than most of the things we consider bedrocks of our democracy, including the Constitution.

Just two days into the first Continental Congress–the 1774 Philadelphia meeting that sought to reconcile rising tensions with Britain–one delegate, a Bostonian named Thomas Cushing, proposed that the next day’s session begin with a prayer. Sam Adams suggested a popular local Anglican minister, the Reverend Jacob Duché. After some back-and-forth over whether one minister could adequately serve a diversely religious group, the motion passed.

That night, news of a possible British attack on Boston reached Philadelphia. The next morning, after opening with a few old favorites and a Psalm, the Reverend Duché broke out into an extemporaneous prayer, riffing on the events of the night before. “Look down in mercy, we beseech Thee, on these our American States, who have fled to Thee from the rod of the oppressor,” Duché said. “…If they persist in their sanguinary purposes… constrain them to drop the weapons of war from their unnerved hands in the day of battle!”

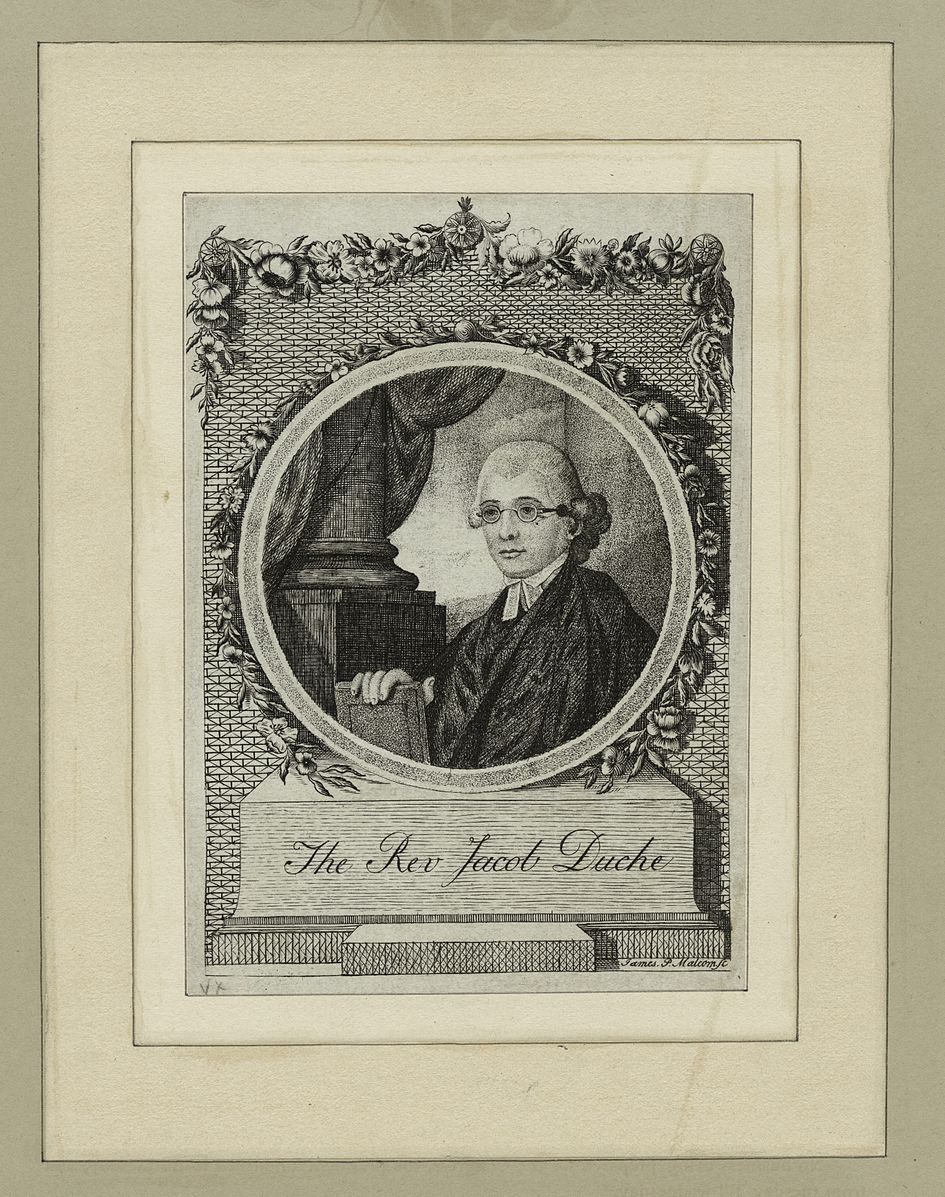

The prayer was a smash hit, and “filled the Bosom of every Man present,” John Adams wrote to Abigail soon after. “It has had an excellent Effect upon every Body here.” Over the next two years, as Americans got serious about revolution, Duché became, in Lund’s words, “steadily more notorious,” kicking King George III out of his list of people who deserved to be prayed for and, in July 1776 becoming the first official congressional chaplain–a position he held until the next year, when he wrote to George Washington entreating him to lay down his arms, was accused of treason, and lost his post.

Reverend Jacob Duché, religious rabble-rouser. (Image: New York Public Library/WikiCommons Public Domain)

At the First Congress–the set of meetings from 1789 to 1791 during which the House and the Senate first created themselves–each legislative sub-branch nominated a chaplain, and set a salary of $500 per year. This also didn’t happen without a fight. As Lund reports, several senators nominated Thomas Paine, a Founding Father loudly opposed to organized religion, for chaplain–the 18th-century equivalent of protesting Homecoming by voting in an all-nerd ticket. But since then, save for a brief period during which volunteer ministers took turns filling in, the position has been an official, paid post.

Throughout history, these chaplains have served not just as openers for each House and Senate session’s main event, but, as reflections of, spurs for, or foils to official business. Take William Henry Channing, the House of Representatives’ chaplain during the Civil War. The Republicans, who controlled the House at the time, told Channing they had chosen him because he “best represent[ed] the antislavery policy” they hoped to push forward. Channing lived up to the task, bringing in an African-American minister and choir to conduct Sunday services and, as Lund writes, “infuriating the Democrats.”

Years later, in the late 1940s, conservative Democratic Senator Clyde Hoey used Chaplain Frederick Brown Harris’s opening prayer to stall a civil rights bill. At the point in the proceedings where the senate votes to approve the previous session’s minutes–usually a formality–Hoey moved to amend the Chaplain’s prayer in order to get across his dissatisfaction with the recently proposed bill. “We debated his motion to amend the prayer for the next two weeks,” his contemporary, Senator Leverett Saltonstall, remembers in his recent autobiography. “His diversion ended the civil rights measure for that session,” and the bill was never voted on.

House of Representatives Chaplain Henry N. Couden opens the day by praying for the recovery of President Woodrow Wilson. (Photo: Library of Congress/WikiCommons Public Domain)

Senate prayers also offer a glimpse of the way tragedy is dealt with on the Hill. On December 8th, 1941, the day after Pearl Harbor and just hours before President Roosevelt declared war on Japan, the Senate Chaplain, Zebarney T. Phillips, led a prayer, asking “help us to find in Thee a sustaining sense of justice which shall become a passion for the amelioration of the wrongs of men.”

In 1963, when word of John F. Kennedy’s assassination reached the Senate, Reverend Frederick Harris spoke of how “the President of the Republic, like a giant cedar tree with boughs, goes down with a great shout upon the hills, and leaves a lonesome place against the sky.” After Princess Diana died, the Senate Chaplain opened with a prayer honoring her.

Prayers from more ordinary times, too, shed light on the day-to-day pressures facing members of the legislative branch. On June 12, 1948, Reverend Peter Marshall gave voice to common complaints: “We grow tired… we feel the strain of meeting deadlines, and we chafe under frustration,” he said. But, he reminded senators, Jesus was “never in a hurry and never lost [his] inner peace even under pressure.”

The juxtaposition of these two prayer types can be particularly telling, and moving. Senate Chaplain Daniel P. Coughlin began his September 10th, 2001, prayer “Lord, on an ordinary September Monday caught up in routine it may be difficult for us to be in touch with our depths.” On September 12th, 2001, he began “O God, come to our assistance,” referencing “gaping holes left in the fabric of our Nation.”

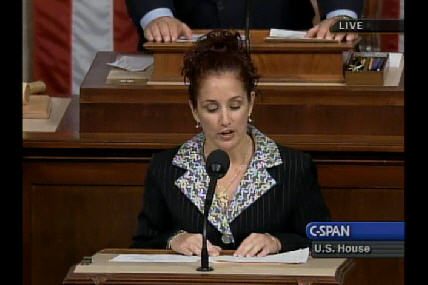

Guest chaplain Rabbi Amy Rouder, opening the House of Representatives on September 14th, 2006. The first female guest chaplain, Wilmina Rowland Smith, spoke in 1948. (Photo: C-SPAN/WikiCommons Public Domain)

The continued presence of official Chaplains has also led to reflection on the nation’s political and religious priorities. The Supreme Court has debated the constitutionality of the position several times, most recently in 2014’s Town of Greece vs. Galloway, during which, Lund writes, they “made it more difficult for plaintiffs to challenge legislative prayer.”

While guest chaplains from various faiths and demographics have been brought in to better represent the diverse makeup of the communities the House and Senate represent, there have historically been very few non-male, non-white, non-Protestant Chaplains. And some of these guest chaplains have received a cold welcome–in 2007, the first Hindu prayer, offered by cleric Rajan Zed, was interrupted multiple times by Christian protesters embedded in the Senate audience.

The current Senate chaplain is Rear Admiral Barry C. Black, a former naval chaplain who was brought to the Senate chambers in 2003. Black is notable for many reasons–he’s the first African-American chaplain, and the first Seventh-day Adventist–but he has also brought new attention to his position due to his sheer zest for the job. Like Channing and Duché before him, he uses his status as the Senate’s conscience to say things others may not, while remaining strictly nonpartisan.

“I see myself as articulating the longings and the concerns of the people whom I seek to minister to,” Black told PBS’s Kim Lawton in 2007. “I have a marvelous opportunity to frame the day for the senators.”

During the 2013 government shutdown, outlets from CNN to Saturday Night Live praised Black for, in the words of Slate’s Dahlia Lithwick, “unloading fistfuls of rhetorical whoop-ass” on the gridlocked lawmakers. On the first day of the shutdown, Black prayed that a higher power “strengthen our weakness, replacing cynicism with faith and cowardice with courage.” Two days later, he had gotten even less subtle, praying “Save us from the madness… deliver us from the hypocrisy of attempting to sound reasonable while being unreasonable.”

By day nine, he was opening the day with “enough is enough,” and asking that God “cover our shame with the robe of Your righteousness.” (It even worked–according to the New York Times, majority leader Senator Harry Reid seemed “genuinely contrite” after the drubbing, and the House of Representatives invited him as guest chaplain.)

More recently, in the wake of another shutdown–this one weather-related–Black asked God to”give our lawmakers the wisdom to seize the opportunities of the myriad seasons.” “May it never be said about their labors that the harvest has passed, but the work has been left undone,” he continued. Attendance at the Senate was sparse that day, with only female senators bothering to show up. But Black was there, making sure that his particular type of storied, contested work got done.

Updates, 2/9 and 3/6: The article has been updated to reflect that Senator Clyde Hoey was a conservative Democrat, not a conservative as the term is more commonly understood today. The date of the Pearl Harbor attack has also been corrected. Thanks to Bill Blood and Wayne Carter for bringing these to our attention, and we regret the errors.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook