India Meets Myanmar at a Bustling Bazaar in Chennai

Indians who were pushed out of Burma have made this market a multicultural haven.

On a bright morning in August, 1965, a young man named Gurumurthy ushered his parents and sisters out of their home in the Burmese capital of Rangoon. They shut the wooden gate behind them, glanced at the stark-white façade of their house for a final time, and began to carry their modest belongings to the nearby port.

As ethnic Indians, Gurumurthy and his family were fleeing a military dictatorship that had stoked the flames of xenophobia in Burma. That morning, they joined thousands on the SS Mohammadia. Several families were fleeing after living in Burma for four or five generations. Together, they sailed past the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and into the Bay of Bengal.

Three days later, the ship dropped anchor in Madras, a major port city in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. The site of the first major English settlement in India, Madras was renamed Chennai in 1996.

Gurumurthy is one of many thousands of Burmese Indians who settled in Chennai. “When we arrived, we were met with a rousing reception and a feast,” he recalls. “And then we were promptly sent to transit camps on the outskirts of the city.”

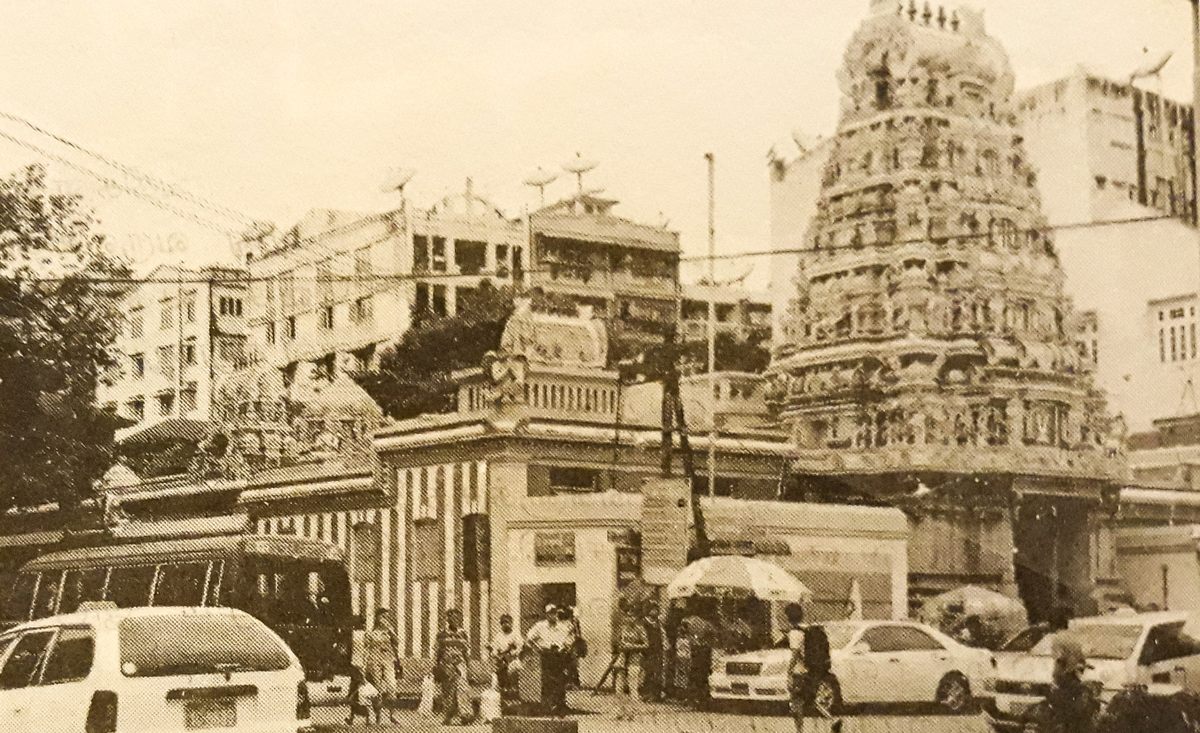

Today, about a half-hour drive from Gurumurthy’s office in MKB Nagar, tiny shops crowd a vast market known as Burma Bazaar, on the northern coast of Chennai. They stretch along the busy Beach Road in the historic George Town neighborhood, selling everything from electronics and imported perfumes to chocolates and toys, at bargain prices. There are stacks of pirated DVDs of films in various languages, hastily moved out of sight in the event of a police raid.

“We started right here, on the platform of Chennai Beach railway station,” Chandran, one of the vendors at Burma Bazaar, tells me. “When we arrived in the sixties, we began disposing of whatever goods—clothes, perfumes—we had brought with us from Burma to earn some money, and discovered that we sold out quickly.”

Once they had exhausted their goods, the hawkers at Chennai Beach station bought more from other, recently arrived Burmese Tamils. What began with a few people spreading towels on the ground to sell items eventually expanded into a full-scale market, comprising nearly 200 shops and gaining notoriety for trading in smuggled goods.

It was very difficult to make Burma Bazaar a permanent feature of the city, says Gurmurthy, who now runs a business distributing liquefied petroleum gas cylinders. He has become a familiar name at the market, largely due to an organization he established in 1979 to protect the interests of fellow Burmese Indians. “It took a lot of persuading,” Gurumurthy says of Burma Bazaar. “But the ruling DMK government at the time was sympathetic to the cause of Burmese Tamils.”

In 1969, the Tamil Nadu government officially recognized Burma Bazaar. Here, in a seemingly random corner of Chennai, the community has managed to build one of the few tangible, lasting links between past and present lives.

The modern Indian-Burmese community has its roots in the middle of the 18th century, after the British Empire waged a series of wars to seize control of Burma (now known as Myanmar). The British treated the Burmese with condescension. One British visitor, D. Clouston, accused them of laziness and claimed that locals were “not as willing as Indians to do hard work for small pay.” British Burma was governed as a province of British India despite large cultural dissimilarities, and scores of Indians migrated there.

Indians in Burma—primarily Tamils hailing from Tamil Nadu, but also Bengalis, Telugus, and other groups—worked as farmers, civil servants, traders, moneylenders, day laborers, dock workers, and security personnel. Many chose to settle down and raise families there. By 1931, the population of Indians in Burma had risen to over a million. In the capital of Rangoon, now known as Yangon, they outnumbered the Burmese.

“Burma has a long-term, love-hate relationship with India,” says Michael Charney, a professor of Asian and military history at SOAS University of London. “Its religion and mythology come from the subcontinent; the hate part comes from the colonial period.” He points out that some Indian immigrants lived in Burma before colonial rule. “But under colonialism, being Indian per se became associated with foreign rule and exploitation, because the British favored many more Indians and Chinese coming in.”

By the 1930s, during the economic devastation of the Great Depression, anti-Indian sentiment continued to grow, and violent riots left hundreds dead—most of them ethnic Indians. Rising Burmese nationalism, and the administrative separation of British Burma from British India in 1937, worsened the insecurities of the Indian population. During World War II, Japanese forces invaded and occupied Burma. “When the British fled in 1942, the Burmese took their anger out on Indians,” Charney says.

Between January and June 1942, nearly half a million Burmese Indians fled Burma. The British reserved ships and airplanes for the exclusive use of Europeans, Anglo-Indians, and occasionally wealthy Indians, leaving at least 400,000 Burmese Indian refugees to make the arduous, months-long journey on foot. Although official statistics are vague, 10,000 to 50,000 people—by some accounts, even 100,000—are said to have lost their lives while walking hundreds of miles to the northeastern Indian border. The trek has become known as the “forgotten long march.”

Burma gained independence from Britain in 1948, and in 1962, the military dictator Ne Win seized power. “Burmese nationalist discourse became increasingly racist,” Charney says, citing a series of discriminatory laws and measures that stripped ethnic minorities of their businesses, lands, and claims to citizenship. The 1962 coup led to yet another wave of large-scale reverse migration, with hundreds of thousands fleeing to India within just a few years. (To this day, the Myanmar government denies full citizenship rights to several longstanding communities in the country, including the Rohingya, Chinese, and Indians.)

Upon arriving in India, Burmese Indians—officially referred to as “repatriates”—were sent to transit camps in the places where their families had come from. Many still spoke the languages of their ancestors. According to state government records, in Tamil Nadu alone, 144,445 Burmese repatriates have been resettled since 1964.

Gurumurthy, who is 75, still remembers that time. “I was working as a traffic sub-inspector in Rangoon before I left,” he says, alternating between fluent English and Tamil. His family had once lived in a thatched-roof house across Burma’s Irrawaddy River, in a region populated by rice mills, but the house they left behind was on Rangoon’s bustling Mogul Street, present-day Shwe Bon Thar Road. He remembers many reasons why Burmese Indians left: “lack of employment, stringent dictatorship, ethnic discrimination, demonetization, and a desire to return to our motherland.”

In addition to finding jobs and housing, Burmese Indians had to learn to integrate into a society that their forefathers hailed from, where they understood the local language yet did not truly belong. Often, they found that they were not accepted by the locals.

The Tamil Nadu government took steps to rehabilitate Burmese repatriates by allocating housing, disbursing loans, and introducing job quotas, but it was a tedious process frequently stifled by bureaucracy and corruption. Some, like Gurumurthy, worked their way up through sheer resourcefulness, creating a comfortable life for their families.

“It was a disorganized life,” Gurumurthy recalls. “Many of our families had lived in Burma for four or five generations. It was like uprooting your life and replanting it in India.”

Gurumurthy got his first job thanks to a bond he had made in Burma, with an Anglo-Indian man named Edwards whom he had once helped. The man’s brother, who lived in Chennai, aided Gurumurthy in finding work at the warehouse of a kitchen wholesaler. For a time, he left the city for another job, but soon decided to return. “Chennai offered more opportunities and room for growth,” he says, smiling and taking a sip of tea. “And so I returned and got a clerical job at the Heavy Vehicles Factory.”

With the help of his connections at the warehouse, he applied to become a cooking gas dealer. “I told myself, if I worked for the government, I could only survive on bribes. I didn’t want to do that. I had to go into business instead,” he says, with a hint of pride.

At Burma Bazaar, a handful of shopkeepers gather around and answer questions about their work here. Chandran, the local vendor, offers to be my guide. It is the middle of the afternoon, and the infamous Chennai heat has caused a lull in activity. A few shoppers walk around, but mostly the vendors linger outside their shops or lean against parked motorbikes.

Chandran informs me that every day after sundown, nearby food stalls—also run by Burmese Indians—will begin selling a variety of Indo-Burmese dishes. Cars whizz past us on Beach Road.

As we make our way to one of the shops selling children’s toys, we pass an elderly man. He is seated at a lone table on one side of the narrow lane, opposite the myriad numbered shops, peddling watches and knickknacks. “He is the original Burmese Tamil,” the shopkeepers say, insisting that I speak with him. “He is the oldest among us, and has a lot of stories to tell.”

The man notices us, and dismisses their statements with a slight wave of his hand. “What is the use of digging up stories that are buried in the past?” he asks. Then he turns back to his table and begins gingerly rearranging the watches on display.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook