Can an Outsider Ever Truly Become Amish?

One of the rarest religious experiences you can have in America is to join the Plain.

Two sisters in their traditional, everyday, Lancaster County Amish attire. (Photo: Tessa Smucker)

The road that runs through the main village of Berlin, Ohio, only about 90 minutes south of Cleveland, is called “Amish Country Byway” for its unusual number of non-automotive travelers and it’s true that driving down it, you’ll have to slow down for the horse-drawn buggies that clog up the right lane. But those seeking the “real” Amish experience in downtown Berlin might be disappointed. It’s more Disney than devout: a playground for tourists full of ersatz Amish “schnuck” (Pennsylvania Dutch for “cute”) stores selling woven baskets and postcards of bucolic farm scenes.

You only see the true Holmes County, which is home to the largest population of Amish-Mennonites in the world, when you turn off Route 62 and venture into the rolling green hills interrupted periodically by tiny towns with names like Charm and Big Prairie. You’ll likely lose service on your cell phone just as the manure smell starts to permeate the air. On my visit this past summer, I saw Amish people–groups of children sporting round straw hats, the young women in their distinctive long dresses–spilling out of family barns, where church services are held, in the distance.

The Amish don’t have any spiritual attachment to a geographical location, the way Jews have to Jerusalem or Mormons to Salt Lake City; this spot, along with Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, is probably the closest they come to an idea of God’s Country.

Earlier that morning, I was introduced to Alex Samuelson*, a baby-faced 31-year-old member of the Beachy Amish-Mennonite faith who, along with his wife Rebecca*, would be my guide for the day. Alex suggested that he might be better equipped to drive and he was right: he glided along the twisting back roads and gave me an orientation to the area not even the all-knowing Siri could have provided, especially considering the spotty service.

As a Beachy Amish-Mennonite, Alex is permitted to drive–the church is what Alex calls “car-type”–but adheres to prohibitions against television, popular music, and limitations on the Internet. (These prohibitions vary somewhat from congregation to congregation, although certain stringencies–like not owning televisions–are uniform throughout Beachy society.) Like all Mennonite and Amish groups, Beachy doctrine is firmly Anabaptist, which means that they don’t accept infant or childhood baptisms. They also believe in keeping themselves separate from the world, which is one motivation behind their Plain garb (although it’s worth noting that the style of dress also differs between congregations.)

Faith Mission church in Virginia. (Photo: Supplied)

I have arranged to meet the couple because they offer insight into one of the rarest religious experiences in America: they are established converts to an Amish-Mennonite group. It is not immediately apparent that they were not born into the culture. Alex and Rebecca look, to be simple about it, like your average Amish couple: Alex has the stereotypical facial hair of an Amish man (beard, but no mustache, a prohibition which harkens back to the days when mustaches were associated with the military) and Rebecca wears an ankle length cotton-polyester dress, her hair in a neat bun underneath her white gauze cap. Alex is an expert in Plain life because he spent years adapting to it, but also because he has a doctorate in rural sociology, and so spends much of his time studying his adopted culture, or “thinking about Plain People,” as he puts it. (He relaxes, I’ll learn later, by tending to his many aquariums.) Because of his work, he’s accustomed to interviewing others about their religious identification, which meant that frequently during the drive, the conversation swerved toward my conversion to Orthodox Judaism. When the ball came back to my court, I asked Alex what it felt like when he first attended a Mennonite church when he was 18, after a year of nurturing a fascination with the culture.

“It’s like walking into a room full of celebrities,” he says. “You’ve thought about these people for so long, and they just feel so inaccessible and remote and just, here you are! They’re all around you!”

Reverent, giddy, almost lustful: it’s the way you’d expect a teenage girl to talk about her favorite pop star, and yet it’s a tone I’ve come to expect among a certain group of people when you invoke the name of the Amish. Before the internet, these “wishful Amish” wrote emotional missives to newspaper editors in areas with large Plain populations; one man I spoke to, who publishes a series of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania guidebooks, composed a form letter so as to minimize the time he spent replying to such requests. Now, the wishful Amish have dedicated internet forums (ironically) on which they write with the feverishness of the unrequited lover about their long-held desire to get close to the aloof objects of their spiritual desire.

Many say they’ve wanted to become Amish for “as long as [they] could remember,” though most of them say they have only seen Amish people on a few occasions, and don’t know much, if anything at all, about Amish theology. Some talk about wanting to find an Amish partner, others, about the fear they won’t be accepted into the community because they are single parents, or divorced, or have tattoos or once dabbled in drugs. Many are hesitant that they won’t be able to fully adjust, and so wonder if it might be possible to stay with an Amish family for a week or two, just to try out the lifestyle. Although a few commenters say they’ve taken the initiative to make their own lives more Plain–given up television, say, or started to dress more modestly–most of them appear to be banking on integration into the community to transform them, like alcoholics who decide to wait until detox before examining the deeper motivations behind their drinking.

An Amish girl mending one of her dresses on her family’s sewing machine. (Photo: Tessa Smucker)

The thread that runs through all the testimonies is one of dissatisfaction, at times, near disgust, with modern society. “As I see it, the world at large is doomed,” writes a single mother of five on the informational site Amish America. One word is consistently invoked to describe Amish life: “perfect.”

The wishful Amish will do what most obsessed people do these days: they’ll Google around a lot, devouring whatever articles or listicles they can get their hands on. During this self-directed study, many will come across the website Alex founded back in 2005, when he was attending college in his home state of Virginia. (He’s currently employed as an adjunct professor of rural sociology at a local university.) Alex built his site in order to provide access to rare documents related to Anabaptist history and culture he had discovered in his campus library (titles include “Amish-Mennonite Barns in Madison County, Ohio: The Persistence of Traditional Form Elements” and “Caesar and the Meidung [shunning].”)

“Then I began getting out-of-the-blue requests from people who were interested in visiting a church, so after a while it was more directed toward an informative website,” he says.

Amish conversion is extremely uncommon, which makes sense: who actually wants to give up modern convenience for more than a week or so? For those who have made the leap, the lived experience of conversion deviates greatly from the fantasies moving across web pages every day; it’s harder, crueler, slower than the hopeful could imagine. It’s also not a static state–for most converts, the emergence of a perfect Amish self never truly occurs.

But we couldn’t get too deep into a discussion of conversion yet, because he began turning the car into the parking lot of the converted elementary school building where his congregation holds services every week. We were late for church.

‘God’s Early Promptings’

Born in 1984 in Loudon County, Virginia, a verdant area long favored by vintners at the base of the Blue Mountain, Alex was raised in a nominally Christian family. His dad owned his own exterior housing repair business; the family lived on 10 acres in an old Victorian home, and attended church on Christmas and Easter some years, but otherwise didn’t talk much about religion. His family, which included his younger sister, was a mostly happy one, although beset by what Alex calls the “typical American plagues”: sibling rivalry, discord between his mother and father, his father drinking too much. To the latter, Alex was especially sensitive.

In second grade, Alex began to experience what he now refers to as “God’s early promptings,” although he didn’t see them that way at the time. He developed an instinctual aversion to designer clothing, particularly shirts with garish logos on the chests. “I felt like it sold me out to something else I didn’t want to sell myself out to,” he said, as I mentally compare this to my unholy childhood yearning for Adidas Sambas. His friends were starting to swear and share “bad ideas” on the playground, and Alex briefly dabbled, but then decided foul language was unequivocally wrong, so he vowed to clean his up.

No voice from the heavens, beseeching him to recognize Jesus. No 49 days spent under a fig tree, contemplating the nature of meaning. No vision of God’s Kingdom as a rural compound full of happy celibates. No, Alex’s awakening was gradual, and in those early days, inconsistent. He didn’t, in other words, connect his distaste for cursing and Polo Ralph Lauren shirts to a burgeoning religiosity, nor did he feel any paralyzing guilt at abandoning his children’s Bible in favor of his DOS video games. But his curiosity about religious life was strong enough that when his younger sister’s bus driver, whom the girl had befriended, offered to take the two children to his Southern Baptist Church one Sunday, Alex agreed. Alex’s sister lost interest after a few Sunday school classes, but Alex, then 13, was hooked. Every Sunday, he’d grab one of the free donuts and then head to Sunday school. A year later, he was baptized.

As a teenager, he was involved in school theater, history club, and Civil War reenactment. Eventually, he took a job that took his love of costuming––a core difference between Amish and other Christians—to a new level. The summer before his senior year in high school, he worked at Harpers Ferry National Park, a historical village located where the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers meet. At Harpers Ferry, Alex dressed in period garb (he had two costumes, one an 1860s shopkeeper and the other a Union private soldier) and gave tours to groups of visitors, including families of Conservative Mennonites. “I started to become obsessed with their appearance,” he remembers. “My friends learned this and they would tell me when Mennonites appeared and I would go on break, grab a root beer and find them and just kind of be near them.” When he tells me this, I remember how I used to similarly side up to Hasidim on the New York City subway in my pre-conversion days, hoping that sheer proximity would allow me to glean some spiritual energy from them.

An Amish teenage boy takes a moment break from his daily chores. (Photo: Tessa Smucker)

Around that time, he was simultaneously examining the practices of Baptist Church to which he belonged, mostly because he felt that no one there could answer the questions he had about certain Biblical mandates, or perhaps they didn’t care enough to ask those questions themselves, which was worse. For example, he found himself particularly struck by a passage in Corinthians that states a woman should have her head covered when praying.

Every man who prays or prophesies with his head covered dishonors his head. But every woman who prays or prophesies with her head uncovered dishonors her head—it is the same as having her head shaved. For if a woman does not cover her head, she might as well have her hair cut off; but if it is a disgrace for a woman to have her hair cut off or her head shaved, then she should cover her head.

Alex thought the teaching was pretty clear, and was unmoved when his pastor told him that it was antiquated convention. What was the point of believing something if there was nothing you could do to actually show it? What had become of modesty, or manners between genders, of embodying the values you espoused, otherwise known as bearing “witness,” in Plain terminology? Such precepts were valued in Victorian times, and in the pre-Civil War South of Harper’s Ferry.

But in this era, in his world, who cared about these things? Only the Plain.

Up until that summer at Harpers Ferry, Alex’s knowledge of the Amish was derived solely, like any ‘90s child, from the Weird Al Yankovic song “Amish Paradise,” and from the few times his family drove by them while on their way to drop him off at summer camp in Northern Pennsylvania when he was a kid. But he entered his senior year of high school after the Harpers Ferry summer with the Plain people in his mind. He bought Twenty Most Asked Questions About the Amish and Mennonites and “hauled it around with [him] everywhere;” he’d occasionally wear button-down shirts and slacks to school and when other students would ask him if he had some sort of presentation that day, he’d cheerfully respond, “Nope, I’m just dressing Mennonite!” (His wife, too, began to sneak out of her house in Plain dress late in high school, much to her parents’ chagrin. In college, she made her own dresses based on pictures of Amish women in a book she checked out of the campus library.) There were no communities near where Alex lived, but a friend of a friend lived in the hills outside Charlottesville and told him there was a Mennonite Church down the road from her parents’ house. One Sunday, he woke up early to drive two hours down to a church not far from Free Union, Virginia (population: 193) and attended his first Mennonite service.

The Rare Amish Convert

An Amish family praying together before dinner. (Photo: Tessa Smucker)

Does love inevitably draw us further into our loved one’s orbit, or can affection thrive from a distance? Can you admire something without eventually wanting to imitate or even become it? And if you do try to become it, can you ever really belong? Or do converts always feel a little like anthropologists, knowing that if things ever got too tribal for their tastes, they could dust off their old clothes and take up residence in their old lives?

These are the kinds of questions that arise when one hears the stories of religious conversion, especially when the conversion requires a complete overhaul of one’s life. Many idolize the Amish world, but few actually infiltrate it. According to the 2013 book The Amish by scholars Donald Kraybill, Karen M. Johnson-Weiner, and Steven Nolt, only 75 people have joined an Amish church and stayed since 1950. One researcher estimates there may be as many as between 150 to 200 converts living Plain lives today, though not all will stay Amish in the long run.

It’s unlikely, in other words, that the wishful Amish writing blog posts about desperately wanting to become Plain will ever do much more than that, let alone seriously pursue conversion.

Still, an intrepid bunch of spiritual seekers manages to go the distance. There are a few “celebrities” among them, like David Luthy, a Notre Dame graduate who was on his way to join the priesthood when he decided to move to a settlement in Ontario and devote his life to documenting Amish history, or Marlene Miller, Holmes County resident and author of the memoir Called to Be Amish: My Journey from Head Majorette to the Old Order, who married her husband while he was living outside the community. Miller, who has now been Amish for almost 50 years, raised 10 children in the church, but will still twirl a baton to amuse visitors. A convert’s success can be aided by the openness of the community that he or she chooses to join, as some settlements, like those in Unity, Maine, or Oakland, Maryland, which is the oldest settlement in that state, are traditionally more welcoming to seekers who may show up there. Others, like the more established ones in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, and Holmes, Wayne, and Guernsey Counties, in Ohio, are less likely accept outsiders.

A map of Holmes County, Ohio, showing the town of Berlin. (Photo: © 2016 Google)

For 14 years, Jan Edwards, now in her late 60s and living near Columbus, did what many considered the impossible: she, an outsider, lived and worked amongst the Swartzentruber Amish. Whereas the Beachy Amish-Mennonites believe in proselytizing, using certain technologies to their advantage, and being generally congenial to strangers, the Swartzentruber Amish are more stereotypically xenophobic and hostile to change. They’re wary of others to the point of chilliness, disdainful of “loud” colors, loathe to speak in English, and proud of their cultural and genetic impenetrability. What is different between Jan and Alex–what her “mistake” was, if one is inclined to view her Amish life as indeed a game that she could have “won”–is the element of faith, or, in Jan’s case, lack thereof.

Jan Edwards was living with her husband and three young children in her hometown of Akron when the race riots occurred in 1968. Martin Luther King Junior had been assassinated, as had John and Bobby Kennedy; the nation was on edge, and Akron wasn’t spared. One night, someone threw a Molotov cocktail threw the front window of Jan’s grandparents’ home, where they had lived for thirty years. They survived, but her grandfather’s leg was badly burned. Her grandparents never returned to collect their belongings. After this, Jan and her husband decided it was time to get out.

“We moved to a country place. [It was] kind of exciting, like maybe we were going to go on a vacation or something.”

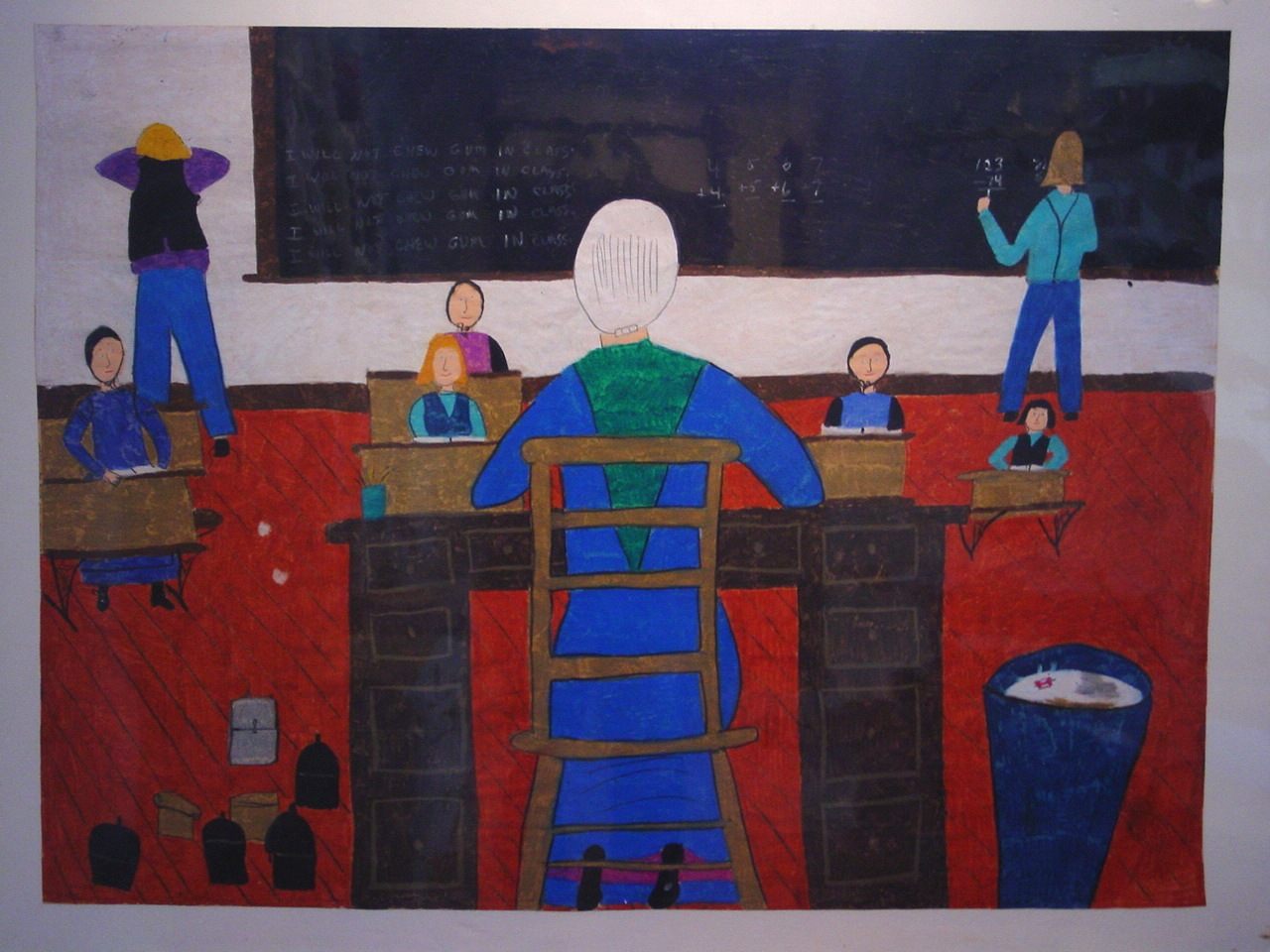

I Will Not Chew Gum in Class, Jan Edwards. (Photo: Private collection/Courtesy of Olde Hope Antiques)

But life in Guernsey County, nearly 20 miles from the nearest shop, wasn’t easy. Jan was learning to farm on the job, while her husband was still commuting to work a long distance from the homestead. Even with his income, they struggled to make ends meet. The Amish lived in close proximity–the nearest house was four or five miles down the road–and Jan started to stop in to buy eggs or honey. Contrary to popular conception, she found her Swartzentruber neighbors to be very warm. “The Amish were downright friendly. Probably because they were so starved for–you know, like the old pioneers, they’d finally see somebody coming up the landing, and they’d throw open up the door. ‘Come on in!’ Even if it was a stranger, they just missed people. They just wanted to talk to somebody and exchange an idea or a thought. A howdy-do or something.”

She and her husband were fascinated–envious, even–of the way in which the Amish seemed to have the living-off-the-land thing down pat. Whenever Jan would go to an Amish family’s house, she would watch them closely: the way they cooked their food, the way they raised chickens, the way they chopped timber.

“You’d observe all that was going on, and take all that back with you when you go home and try to see if you’d learned anything,” she said. “I guess we were copycats to an extent.”

I went to meet Jan on a cold October Monday some months after my trip to Holmes County. Leading up to my visit, she hadn’t seemed terribly enthusiastic about me stopping in–“this is a very busy household,” she wrote in a letter–perhaps because she’d already told her story a few times, to a couple of local newspapers, and on the PBS television series American Experience. But once I am there, drinking her freshly brewed coffee and enjoying some out-of-this-world strawberry crumble, she seems to enjoy being faced with some tough questions, and can, like Alex, talk about the appeal of Amish life without reducing it to a starry-eyed romanticism, or, in her case, leaning solely on bitterness or soppy nostalgia.

In person, Jan gives off a host of contradictory vibes: spry and world-weary, wise and undiscerning, forthcoming and guarded. Her house is dimly lit and decorated with the odd tchotchke; some of her paintings of Amish life–equal parts charming and eerie, like a lot of art brut–lean against the walls. She has a gaggle of grandkids and great-grandkids who spend a lot of time with her and wreak happy havoc on place. But for now, she talks of her life with the Amish, and she sounds like she’s been to war.

“I couldn’t do it again, because I was there too long, maybe. I saw too much and heard too much. I became aware.”

“It” was a slow progression into life with the Swartzentrubers, one that unfolded over the course of a decade, during which period the whole brood–Jan had six more children over the years there–began to dress Plainly, attend church services, and learn Pennsylvania Dutch, the lingua franca of the Old Order. Her children attended Amish schools, and the family participated in barn raisings, funerals, and quilting circles. Eventually, she and her husband formally joined the church (most of her children at this point were still too young to be baptized, as Amish don’t usually accept a baptism before the age of 16.)

Mostly, she joined because she feared that she would never be fully accepted as one of them unless she did. She did her best to tow the line and “reject everything that could be possibly rejected,” like toasters and windows on her buggy and the news. She could chat in Pennsylvania Dutch to the ladies after church. “I had figured out how to grow everything and wash everything and do all the household and farm kind of things.” She never used bright greens or deep purples in her quilt. She was in the very ordered zone. Besides, Jan had never seen the theological difference between herself and the Amish as a huge barrier–she and her husband were Methodist and Baptist, respectively, and “conservative, I guess”–so she didn’t really consider joining an act of religious renunciation and/or rebirth. The Amish were Christian, and they didn’t do “bad stuff,” and that was common enough ground for her. Most of the Amish people she knew, particularly the women, couldn’t point to the scriptural passages that were the basis for their customs–they just did as they had always done. But this resigned attitude didn’t disturb Jan too much at the time.

“It’s in the background, somewhere else. Because the day-to-day life is so engulfing. You’re just trying to keep warm and get enough to eat and all the social interaction in a settlement,” she says. “You’re just totally busy from bedtime to bedtime… it’s not until way down the line that you think, ‘Oh, hm.’”

After she joined the church, she remained in the zone for only a year or so. Like a frog in a pot of boiling water, she realized that the heat had been turning up while she’d been distracted. Her older children were teenagers now and spending more times with their friends. They brought home tales of rebellion that are de rigueur for the secular world, but surprising in such a cloistered one: drinking, drugs, a little sexual experimentation. Jan and her husband hadn’t ever considered that this happened in the Amish world; they thought maybe the other parents didn’t know, and they should all get together and talk about how to solve the problem.

A teenage Amish girl’s closet. (Photo: Tessa Smucker)

As even-keeled as she is in person, Jan had never really forsaken the independent part of herself that spoke out when she deemed it necessary. “Am I a feminist? I don’t know that. I don’t even know what a feminist is,” she says. “But I have strong opinions. And would act on them.” Whether that meant insisting she get the things she needed for the house–new plates from an auction sale, thread for darning, flour for baking–or informing on her sons’ friends, she was prepared to do it.

But there was the rub: the other parents didn’t want to know what their teenage kids were up to. To confront the problem would be to acknowledge it, which was anathema to Amish sensibility. Better to just chalk it up to kids being kids, and hope that it passes.

“But the consequences of that is disastrous,” she notes, “It’s just disastrous what happens to a lot of people. And that disillusioned us.”

Meanwhile, Jan’s eldest son, Paul, married a bishop’s daughter from down near Holmes County. From the moment she arrived, it was clear Paul’s wife was emotionally distressed, though Jan could never determine the genesis of her unhappiness. She told the family she had had a miscarriage–Jan isn’t convinced she actually did–and couldn’t help around the farm as a result. Instead, she stayed in bed for two months, occasionally waking Jan, whose youngest was two at the time, in the middle of the night to “pull pain from her arms and legs” in a Reiki-esque fashion. During this time, she asked her sister to come live with her, and the two would often faint simultaneously, basically on command; once, Jan and her husband found them both lying on the floor, so they took them to the emergency room, but the doctors said they were fine. In later years, she’d hide under the chicken coop for hours when upset, or give her children vodka to drink to keep them subdued.

But despite her eccentricities, there was a sense among the Edwards family that they had to behave in front of her, because if they did something untoward–say, converse in English as opposed to Pennsylvania Dutch at the dinner table–she might tell someone. Eventually, the strain of catering to her whims and keeping up appearances became too much, and Paul and his wife moved to a rented farm on a different plot of land. After that, Jan and her husband missed two church services (Old Order Amish hold church every other Sunday); when they didn’t attend for the third one, they were excommunicated.

Overnight, what had been their communal and personal identity was swept out from under them.

That was around 26 years ago, and Jan is still struggling to adjust to life outside the Amish (her husband passed away in 2011.) “I think, while I was gone, while I was out, the world changed. It’s not the same world anymore. I haven’t actually adapted very well. People don’t cook their own food. Mothers don’t raise their own babies. = People don’t teach their own children anything,” she says, her head tilted slightly downward toward the wooden kitchen table. There are many things she misses about Amish life: the camaraderie, the stillness at night, with no passing traffic or vibrating phones or even lamps to slice through the darkness. But it’s not like she spends all her time pining for the past, either; there’s a lot of stuff she doesn’t miss, like having to stifle the smallest expressions of her individuality, or sitting through incomprehensible church services in High German. It’s not that one place or another would be better–it’s that no one world is truly a home, not anymore.

“I absolutely don’t fit!” she says with a laugh, and in my head, I fill in the obvious clarifier: anywhere. I start to feel sad for her, until I notice she’s still smiling. “But you get over it. And maybe fitting in isn’t a good goal anyway.”

Not a Historical Reenactment, A Real Person

The Sunday in May that I spent with Alex and Rebecca isn’t the culmination of years of pining for Amish-Mennonites, but still, I had, upon entering the church, a moment not unlike the one Alex described having 14 years prior: I became tense, excited, and in a state of near-disbelief. Like many Americans, I carry with me preconceived notions of Amish-Mennonite people, and one of these is that Amish-Mennonites exist only when they are being gazed upon by outsiders. Of course I know intellectually that this isn’t true, but some part of me has absorbed this conception of the Amish as relics, and their homelands as being, like Plymouth Village in Massachusetts or Colonial Williamsburg–or Harpers Ferry, for that matter–essentially historical reenactments, meant not for the people doing the reenacting, but for the visitors.

A room full of Amish-Mennonites in their trademark garb is enough to disabuse one of that notion. The first moment, you might think that the mannequins in a display at the American Museum of Natural History (if they had a dedicated Anabaptist Wing) has suddenly come to life; then, a child wiggles in her seat, and a person quietly clears his throat, and you realize these are flesh and blood people. Here you are! They’re all around you!

Here’s what I see: services are held in a large, unadorned room that must have been in its previous incarnation a cafegymnatorium. On the left side sit the men, and on the right, the women. There is a long mirror on one of the walls, which I deem noteworthy. Down the middle of the room–bisecting the genders–an aisle leads to a small stage where a man stands at a lectern addressing the group. I am too busy soaking in the visuals to really listen to what he’s saying, and his voice is so quiet and measured that it doesn’t disrupt my reverie. The women are all wearing long, monochromatic dresses, and the odd one dons a sweater–the palette covers the primary colors, but no garment includes more than one pigment, or has any flourishes of any kind, like a little lace on the sleeves or a Peter Pan collar. No one wears jewelry. The adults briefly glance back at me, the resident outsider, whereas the kids turn and stare at me with deep, wide eyes like tiny lakes. Every last one of them is stunningly beautiful.

“There was a church picnic yesterday,” Rebecca writes (in immaculate handwriting) on her notepad, which she then passes to me. “That’s why everyone is sunburnt.”

When the devotional is over, the group rises and sings a hymn entitled “Our God, He Is Alive.” The singing is soft and a capella, as Amish-Mennonites frown on musical instruments and solo performances, but the hymn itself has a quick tempo and a not-uncomplicated call-and-answer chorus, which the parishioners–who don’t learn how to read music–handle with aplomb.

There is a God (There is a God), He is alive (He is alive)

In Him we live (In Him we live) and we survive (and we survive)

From dust our God (From dust our God) created man (created man)

He is our God (He is our God), the great I Am (the great I Am)!

Church service runs maybe two hours, which isn’t trying for me, because I spend at least that long in synagogue every Saturday. There are devotionals, hymns, moments of silent prayer; it’s Mother’s Day, so there’s a lot of discussion about loving our mothers, who are the foundations of the household though they might act more behind the scenes than their hirsute counterparts. I can hear the tut-tutting of my ardently secular peers in my head–the patriarchy silences the Mennonite women!––and attune my ears to anything that might offend liberal sensibilities, but not much comes up. One speaker comments that the society is crumbling, but you hear that from all camps these days; another talks about our duty to love our fellow human beings regardless of their politics, race, or religious belief, which I think we can all get behind. At one point, a group of church ministers reads a letter of recommendation they had drafted on behalf of a former member (when a member moves, they need such a letter to join a new church.) They ask the congregation if everyone deems the letter acceptable. Everyone silently agrees that it is.

Once during the service, the congregation kneels down for prayer; this we do with our backs to the lectern and our elbows on the seat of our chairs, like we are children saying “Now I lay me down to sleep” before getting into bed. I sneak a few furtive glances around the room, and then look up to Alex, who is kneeling in a back nook, where there is built-in bleacher-style seating. His eyes are closed and his hands are clasped. I wondered how natural prayer feels to him, how fervent or lyrical or intimate in tone his outpouring is, but his face betrays no fiery mental activity. He looks serene. For a person raised religious, prayer can become routine, even robotic, but for the convert it can also be understood as a skill to be honed, and your facility in it can come to measure, for yourself and those around you, your worth as a Jew or an Amish-Mennonite or a Muslim or whatever the case may be.

Watching him there in church, I think of one time, when a friend and I–both studying to convert to Judaism–were discussing an acquaintance of ours, a woman who had converted as a teenager and had at that point been living an Orthodox life in Boro Park, Brooklyn for around ten years. “I mean, you should see her daven,” Elizabeth said, using the Yiddish word for pray. “It’s incredible.”

Always a Misfit?

After church services, Alex and Rebecca take me to pick up my rental car, and then I follow them to their abode, which is a small house sandwiched between two other small houses, just on the other side of Berlin’s main drag. Rebecca goes into the kitchen to finish preparing lunch (chicken, applesauce, coffee) while Alex and I settle in the living room to talk about adjusting to Amish-Mennonite life. Their home is so close to the road that I can hear through the open window the clip-clop of horses’ hooves as buggies approach and then pass outside, which they do often. The space contains seven enormous aquariums filled with tropical fish; there are lights throughout, but none of them are turned on, and an old laptop sits closed on a table. A small bookshelf houses a handful of Christian books, as well as a few authored by Alex himself, including a coffee table photography book of Amish-Mennonite churches, as well as his taxonomy of the different styles of head coverings worn by various Plain communities. As I flip through a copy, lingering momentarily on a photo spread, he explains that he believes the cap (think bonnet) is superior to the cloth style (think scarf). “There’s quite an undercurrent now for the church to be moving toward the cloth style,” he says. “And given that the churches hold such a revered place in the Plain peoples’ lifestyle, is the switch in covering style indicative of a shift away from the church’s importance in people’s lives?”

These might seem like petty details to an outsider, but for Alex, no aspect of life is too casual to be deemed irrelevant to Plainness. This is actually not unique to him–whereas the Amish are legitimately above all the consumerist silliness that characterizes so much of American culture, they are also in other ways more mindful of aesthetic choices than the non-Plain masses. As academic Sue Trollinger puts it in her book Selling the Amish: The Tourism of Nostalgia, “[The Amish] know better than most Americans that it matters how you style your hair, the sort of pants you put on each morning, what kind of vehicle you drive to work.”

A teacher from an Amish one-room school house corrects papers after a day with her students. (Photo: Tessa Smucker)

At 18, Alex enrolled at Eastern Mennonite University in Harrisonburg, so as to be within driving distance of the church. He generally preferred the church to EMU, where he was getting a degree in geography; the school was too mainstream–“no distinctiveness whatsoever”–for Alex’s taste. He became active in the community, attending Wednesday evening and Sunday morning services faithfully, and eventually joining the youth group and the choir. He adopted a more conservative uniform, though other than that, a lot of his behavior already conformed to church standards, because he had been working since high school to give up movies, the radio, involvement in sports, and television. (The last show he watched was The Simpsons, which was tough to let go of. He looks momentarily enticed when I tell him it’s still airing.)

Two years after he began attending, he formally joined. But even over the three years of membership that followed, he worried that he was doomed to always be a misfit. For one, he often felt like the social bull in the china shop of Amish-Mennonite life. He projected his voice in choir, spoke up in meetings, and deviated from the norm in ways the community didn’t understand, like maintaining his interest in classical music. “Plain People have prescribed forms of deviance,” he explains. “If you’re going to get an instrument and be naughty, you’re going to get a guitar, but the flute? It created too much question for them.” Because he hadn’t grown up in the culture, Alex couldn’t pick up on the way the group subtly expressed their disapproval–a pregnant pause, say, or a swift glance, but never a verbal rebuke–and often felt like he was the last to know when he was doing something unacceptable. “When I did violate some sort of norm, everyone else already knew it, and I was just set back from really being accepted by these people as one of them.”

Conflict also arose because, Schoenberg flute solos aside, Alex was in many ways a little more conservative than the group. While church officials were discussing abolishing certain sartorial codes–say, ditching a full button-up shirt for men in favor of shirts with one or two buttons at the collar–Alex was dressing consistently more conservatively. Sometimes, he would wear suspenders, and the other men would brusquely inform him that they dropped that requirement years ago, as if piqued they were being outdone by a new kid. He was always trying to organize evening activities for the male youth–Bible study, seminars on mission work abroad–only to find out the kids were planning to go sledding instead. After one evening when turnout was particularly disappointing, Alex was so depressed he stopped attending that church for the next three months, service-hopping from one Plain congregation to the next, hoping in vain to find somewhere that checked all his boxes. He started underperforming at his job as a transportation planner. Doubt consumed him: Do I really want to be with this people? Do these people even really want to be who they are? If the keepers of these things don’t even value them, then what value do these things have?

An Amish farmer mends a harness with his son, c. 1941. (Photo: National Archives 83-G-37538/Public Domain)

The move to Ohio in 2009, precipitated by a scholarship to study for a PhD in sociology at Ohio State University, proved re-invigorating. “It was really a chance to begin taking control again of what I want to do amongst these people. How I want to be amongst these people. Put some of what made me me back in middle school and high school to work in this setting.” In Ohio, he did join a new church, but with a greater understanding of how he would have to compartmentalize in order to be both his autonomous, individual self and his devout Amish-Mennonite self. That old-self found its outlet in academia, whereas the devout self prays, works to yield to the authority of the group, and regularly gives speeches to the church youth about cherishing their heritage. It’s harder for them to value Plain faith and culture, he knows, because they, like most people, find it easy to take for granted what’s always been.

In a way, Alex has come to realize what the wishful Amish of the internet haven’t fully grasped yet: that the Amish universe and its denizens are not perfect. They don’t have a vested interest in your quality of life–spiritual, technological, or otherwise–anymore than you do in theirs. When the wishful Amish express disappointment at this–“Why don’t they seek to try to save this terrible world?” as one Internet commenter opines–they are ignoring the fact that the Plain-from-birth are not operating as full-time beacons of goodness, but as people whose “private convulsive selves,” as William James wrote, more often than not trump ideology. They’re also not spending every moment musing on the purpose of community and separatism. They’re just humans: they get tired of their lives, they skirt convention, they just want to go sledding when they should be reading. It takes someone like Alex, acutely aware of the socializing forces at work on them, enamored of and devoted to the faith they all share, a part of and yet a stranger in the community, to remind them of what they have.

Suddenly, I’m thinking about something I saw in church earlier that morning: in front of me sat a girl, maybe 10 or 12, a white cap pleated neatly around her light brown bun like a cupcake wrapper. A few times, she reached her skinny arm back, drew a silver pin from deep within her tightly coiled hair, moved the pin a fraction of a millimeter, and pushed it back into place. A tiny motion, a meaningless one maybe, but I felt like I was watching a dance savant, moving without thinking about the next step, or about any of the technicality behind her piece, unaware, in many ways, that she was dancing at all. This is the kind of cultural fluency Alex always wanted, but can never have. This is the warmth of effortless identity people like Alex and me will never know. But that’s okay: though we’ll stumble over the wordings of our invocations sometimes, we’ll make up for it in the love we feel for our little worlds, and in the ways in which, as perennial outsiders, we can proclaim their worth with a special sort of authority.

“In the early days, I would have wanted to hide the fact that I didn’t grow up this way. Now I embrace it. Now it’s part of me.” At this, he grins and opens his arms, palms out, as if to say, here I am.

Author’s Note: “Alex” and “Rebecca” are not the real names of two people interviewed. They felt strongly that they should not be identified by name out of respect for their faith’s general belief in the body above the individual.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook