Changes in Climate Have Always Made Things Worse for (Accused) Witches

Stop messing with the weather, grandma! (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

This week, 2015 was officially declared the warmest year on record. Droughts are worsening, resources are dwindling, and sea levels are rising—alongside witch killings, if the past has anything to say about the present.

Witches probably make you think of the infamous witch trials of medieval Europe, which led to the execution of as many as one million individuals between the 13th and 19th centuries. These trials, as well as those that occurred in Salem, Massachusetts during the late 17th century, have long been fascinating for their oddity and inexplicability.

There have been all sorts of hypotheses about why the accusations might have come about—tensions between Roman Catholics and Protestants; a need by men of medicine to dispose of midwives and female folk healers; scapegoating; socio-political turmoil; a way to eliminate the diseased, mentally ill, or social outcasts; class conflict, superstition, or simple misogyny.

But what about the effects of weather and climate? Could they have influenced all the unfounded accusations and mass lapses in logic? More than one researcher believes so.

Talk about controlling the weather. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

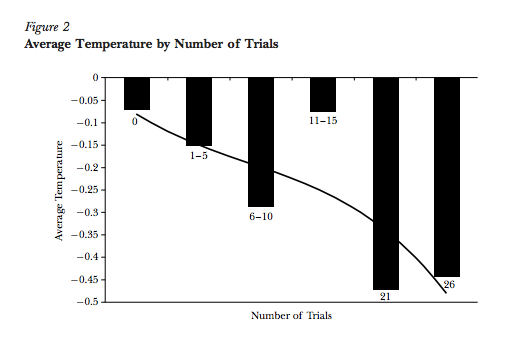

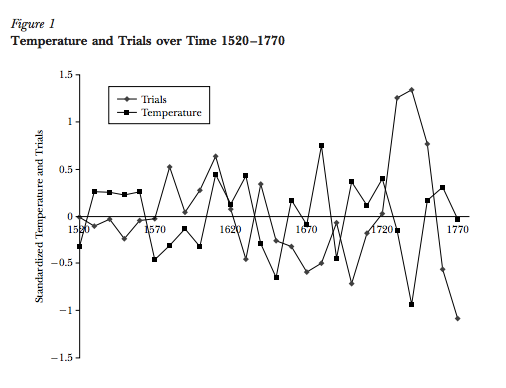

While climate, and its changes, is something a lot of humans prefer to ignore, it wiggles its hot-and-cold fingers into everything, and witch hunts are no exception. In a paper published in 2004, Brown University economist Emily Oster argues that the witch persecutions that took place in Europe between the mid-16th and end of the 18th century were influenced by noticeable weather changes during the period. A 400-year “medieval warm period” was followed by a “little ice age” before things started warming up again—factors that would have severely affected food production. The cultural framework at the time suggested that witches had control over the weather and thus could be justifiably persecuted.

Oster collected data on witchcraft trials and looked at correlations between weather and witchcraft across several regions. While Oster admits that drawing strong conclusions on such potential links is difficult, the fact that her results show even marginal statistical significance, she writes, is suggestive, especially when you look at the close overlap between weather, food production, and economic growth during these times.

Though Britain passed the Witchcraft Act of 1735, criminalizing witch accusations, witch killings still take place today in a number of countries across the globe. And, just like hundreds of years ago, extreme weather can play a role.

In his 2005 paper, “Poverty and Witch Killing,” Edward Miguel of the University of California, Berkeley finds that in present-day rural Tanzania, twice as many witch murders take place in years of extreme rainfall than in other years. In his evidence from 67 villages across 11 years, the victims are almost entirely elderly women and typically killed by their own relatives.

A negative correlation here between temperature and witch trials. (Image: Emily Oster)

A negative correlation here between temperature and witch trials. (Image: Emily Oster)

This is not unique to Tanzania. In northern Ghana, thousands of women over the past decade have been attacked or driven from their villages, often after struggles over household resources. Such violence has been getting worse since 2002, with similar cases in Nepal, Papua New Guinea, India, and parts of Latin America and Africa.

In a 2010 poll of 18 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, over half of respondents believed in black magic. As in 17th-century Europe, witches in these communities are still seen as bringers of evil, misfortune, disease, and death. In some places, witch killing is considered a public service, pinning blame for things outside of human control. In others, the legal system even defends the practice of witch killing. In parts of Nigeria, Evangelical preachers are even labeling children as witches, leading to money-making, fear mongering, and the abuse and murder of hundreds or thousands of children.

In India, witch killings, which can be truly brutal, show up weekly in newspapers; upwards of 2,500 people accused of witchcraft were killed between 2000 and 2012. Like elsewhere, witches in India are almost always women. Ramesh Singh of the Indian Social Institute wrote:

“Often a woman is branded a witch so that you can throw her out of the village and grab her land, or to settle scores, family rivalry, or because powerful men want to punish her for spurning their sexual advances. Sometimes, it is used to punish women who question social norms.”

A woman gets old and suddenly she’s a witch. (Photo: Vasantdave/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Robert Thurston, author of The Witch Hunts: A History of the Witch Persecutions in Europe and North America, doesn’t think that the climate arguments hold much water. He says there are too many counterexamples—periods of bad weather and faltering economies where little happened by way of witch killings, or a town with vicious killings neighboring a town with none.

Thurston points out that women were the ones around the house, cooking the food and taking care of the children, so it was easier to blame them for mishaps. Women, and in particular menstruation, were mysterious to men, spurring different kinds of legends and ideas. On top of that, older women tended to look funny, he says, with warts, lumps and wrinkles.

Older women, simply put, have everything going against them.

For a Tanzanian village like this, droughts are not a good sign for old ladies. (Photo: Rod Waddington/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 2.0)

There’s also the unavoidable factor of geronticide, the killing of elders, which has existed across all sorts of cultures, with and without the label of witchcraft. There are a number of examples where the availability of food resources directly affects the treatment of the elderly. Icelanders, Amazonian Bororos, Fijians, and Australian Tiwi are just a few examples of groups known to have practiced death-hastening activities against the elderly.

Mitch Horowitz, author of Occult America: The Secret History of How Mysticism Shaped Our Nation, has heard the climate thesis before and thinks it has some validity. “Clearly the witch craze, generations ago and today, involves regional superstitions, very old propaganda against the targeted group, family or local conflicts, and often age-old scapegoating of a certain group,” he says, specifying “women today in the South Pacific, Jews in Tsarist Russia, orphans in Africa, Gypsies in Western Europe.” In periods of instability and strife, humans naturally reach for someone to blame or explain what is going on.

Where’s an old lady meant to go when society spurns her? (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

But there may be some possible solutions. One thing that might help is the introduction of measures that predict and prevent famine, such as the Famine Early Warning System (FEWS). Another is support for society’s elder members. After an old-age pension was introduced in South Africa’s Northern Province in the early 1990s, witch killings there dropped dramatically. Granted, other political and social changes were taking place during the same period, but one imagines that such a pension could only help the grandmas at risk of being accused witches. Unfortunately, many countries, like Tanzania, couldn’t afford the measure even if they wanted to.

There is clearly a multitude of social and cultural factors at play when it comes to witch hunts, both in the past and in the present. Killing suspected witches is a way of addressing the seemingly unexplainable (sudden illnesses, crop failures, foreign threats), but the factors influencing these killings are not so easy to explain. Regardless of whether climate has anything to do with it, little old ladies are still being lit on fire, stoned, and beheaded for being little old ladies, chosen to bear the brunt of society’s ills. Who, here, is practicing the real black magic?

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook