Mapping the Lost Countercultural Hotspots of Cambridge, Massachusetts

Local librarian Tim Devin has found hundreds of buildings that once housed utopian groups.

The building at 16 Lexington Ave looks like a lot of other Cambridge, Massachusetts houses. It’s a two-unit home, with a peaked roof and a wide front porch. In the early 1970s, though, the building served a different purpose: It was the headquarters for a militant feminist group called Cell 16. Issues of their journal, No More Fun and Games, poured out of the front door and into mailboxes nationwide. The house even hosted the group’s martial arts studio.

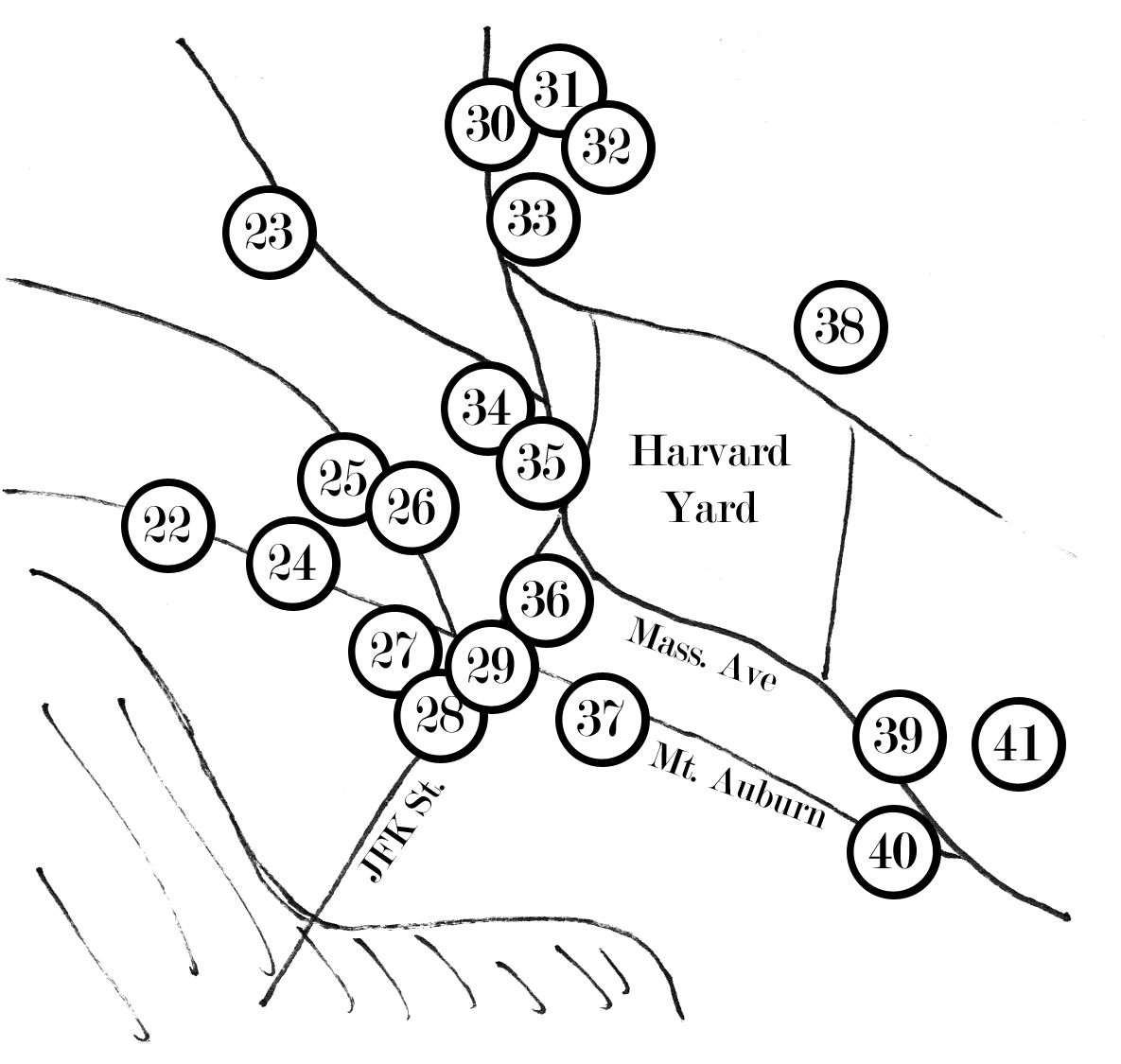

It wasn’t just them. In the 1970s, Cambridge, Boston, and their environs were filled with countercultural hotspots. Wander a few blocks from Cell 16’s former home base, and you’ll find a whole cluster of former utopian hubs: a youth counseling center, a draft information office, the home base of a commune that wanted to buy out the whole neighborhood, and the headquarters of the Citizens League Against the Sonic Boom.

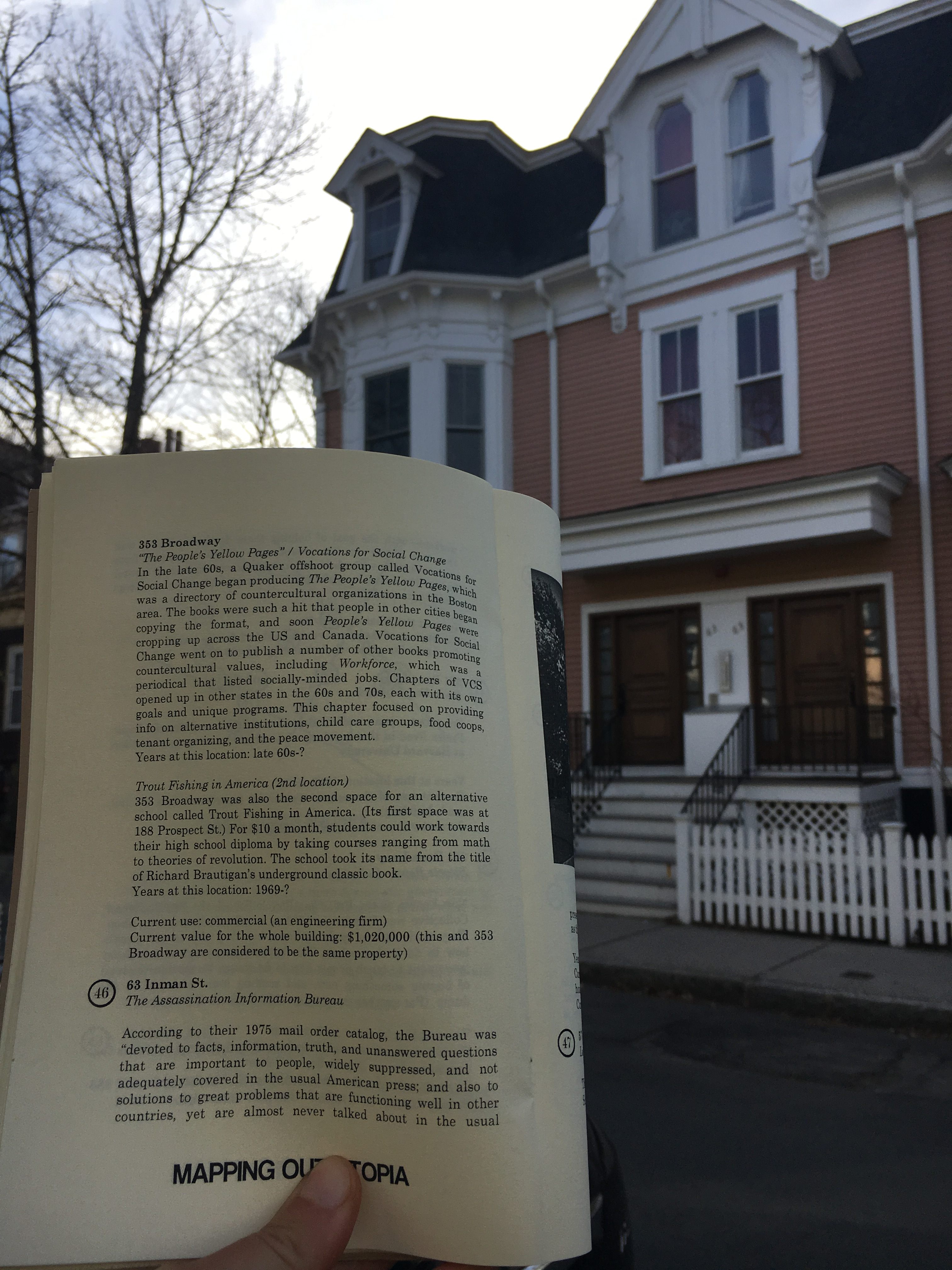

All these radical places—and many more—live again in a series of zines called Mapping Out Utopia. Created by Somerville librarian Tim Devin, the series catalogs and situates hundreds of alternative schools, clinics, businesses, and organizations in the Boston area. Some, like all of the ones mentioned above, are long defunct. Others are still thriving. All fall under the umbrella of what Devin sums up as “counterculture:” groups that were trying to change the world by changing their own daily lives.

Devin came to this project because he was trying to make a small change in his own life. “I wanted to share things with some of my neighbors—tools and things like that,” he says. “I started wondering how you actually do that. So I started reading about the ’60s and ’70s.” Research led him to a national magazine, Communities, that started in 1972. “It’s all about hippies, sharing, communes—stuff like that,” Devin says. “They wanted people involved, so they listed all these different organizations. A lot of them were in the Boston area, which I thought was kind of interesting.”

Further digging revealed similar compendiums: Alternative America; the New Woman’s Survival Catalog. Some had blurbs and information; others, just names and addresses. “Being a dork,” Devin says, “I started mapping them out.”

Ask for the golden age of American counterculture, and most people will name the 1960s. But if that decade was all about experimentation, the ’70s were the equivalent of clinical trials—“a time for the grassroots to build on what had gone before by forming more organizations, nonprofits, and businesses,” as Devin writes in the zine’s introduction, even if the decade formed “a bleak backdrop for all of these utopian impulses.” The U.S. was in the midst of a recession and still embroiled in the Vietnam War, two events with local repercussions in Massachusetts. Unemployment in the state reached 7.3 percent in 1973, much higher than the national average. In 1970, anti-war protesters were tear-gassed by police in Harvard Square.

The area also had its own unique problems to deal with. Massachusetts was suffering from an opioid epidemic, and Boston was roiling with racist violence in response to the desegregation of the city’s public schools. As Devin writes, these events inspired people to think outside the box. They also created conditions where it was possible for them to come together to do so: “All of this is why apartments and storefronts were cheap and readily available to idealistic, countercultural people and groups that didn’t have much in the way of bank accounts,” he writes.

Collectivity begat collectivity. “Some organizations bunked together,” says Devin. “Or they had extra space, so they sublet.” He points to 188 Prospect Street, an apartment building on a main thoroughfare that once hosted three different groups: a cooperative photography studio, an organic bulk food store, and an alternative school called Trout Fishing in America, after a book by Richard Brautigan. “It became this countercultural headquarters—a command center kind of place,” he says.

The organizations in Mapping Out Utopia run the gamut. Some—such the Women’s Research Center of Boston, which published research on equality in the workplace— took on broad issues. Others, like the Boycott Gulf Coalition, which was run out of a small room at Harvard University, were more niche. Many served particular marginalized communities, like the Fag Rag Collective, which was headquartered in Central Square and had to fight with the postal service to send out their newsletter, the Fag Rag. Some now seem ahead of their time; a few, like Clivus-Multrum USA, still seem ahead of ours. “They investigated recycling toilet water and human waste,” says Devin. “That’s just so forward-thinking.” (Though they’re no longer headquartered in Cambridge, Clivus-Multrum still sells composting toilets.)

And then there were organizations that existed mostly to help other organizations—“what I think of as ‘countercultural support,’” Devin says. Some managed fundraising for their fellow groups. Others provided communal childcare, or legal advice for people trying to do things like co-own cars. “It makes sense—if you’re trying to explore a different way of doing basic everyday things, then the basic everyday support mechanisms might not work for you,” Devin says. “You need somebody else to back you up.” (One countercultural support group, Hacker’s Heaven—a do-it-yourself auto garage, where patrons rented space and tools by the hour—is perhaps the book’s most famous spot. It was founded by brothers Ray and Tom Magliozzi, aka Click and Clack of Car Talk.)

There are 91 entries in the Cambridge issue, and dozens more in the Boston one. (“And that’s not even all of them,” Devin says. “I’ve since found a whole bunch more.”) He’s in the midst of a follow-up work focused on Somerville, Brookline, and the surrounding suburbs. Each entry contains the address, the organization’s name, how long it spent at the location, and a short blurb.

It also names the space’s current fate: what’s there now, and the property’s market value. “The punchline is, not much of that stuff would be able to be there now,” Devin says. There are some holdouts—Broadway Bicycle School, a collectively owned bike shop, is still around, as is the Fayerweather School, an alternative school that was once linked to the Fayerweather Community. The Cambridge Cooperative Club, a co-op house for “people in transition,” has even expanded.

But many more have moved or folded. The large building at 56 JFK Street in Harvard Square once housed a church-sponsored social justice initiative, a sustainable agriculture group called Massachusetts Tomorrow, and the group of transportation activists that defeated a massive highway project. Now, as Devin writes, it’s home to “Shay’s Bar; a liquor store; a restaurant named Orinoco; a lingerie store; [and] offices.”

Cell 16 moved twice before closing up shop—their original space is now a two-unit house, worth nearly $3 million. It’s hard to imagine paying that rent by running a feminist group and martial arts school. Greenhouse, a holistic counseling and therapy center, was paved over in favor of a parking lot, a conclusion straight out of a Joni Mitchell song. “And what does that mean, right?” Devin continues. “If you need gathering space, if you need meeting space, if you need a professional office, what happens when you can’t afford to be in a city? Does the city suffer?”

Devin himself feels motivated by these erstwhile radical spaces, some of which he walks by every day. His neighborhood-level sharing system didn’t quite happen. “But just looking at this stuff, it sort of normalizes the idea that you can experiment with your life,” he says. “I’ve taken that to heart.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook