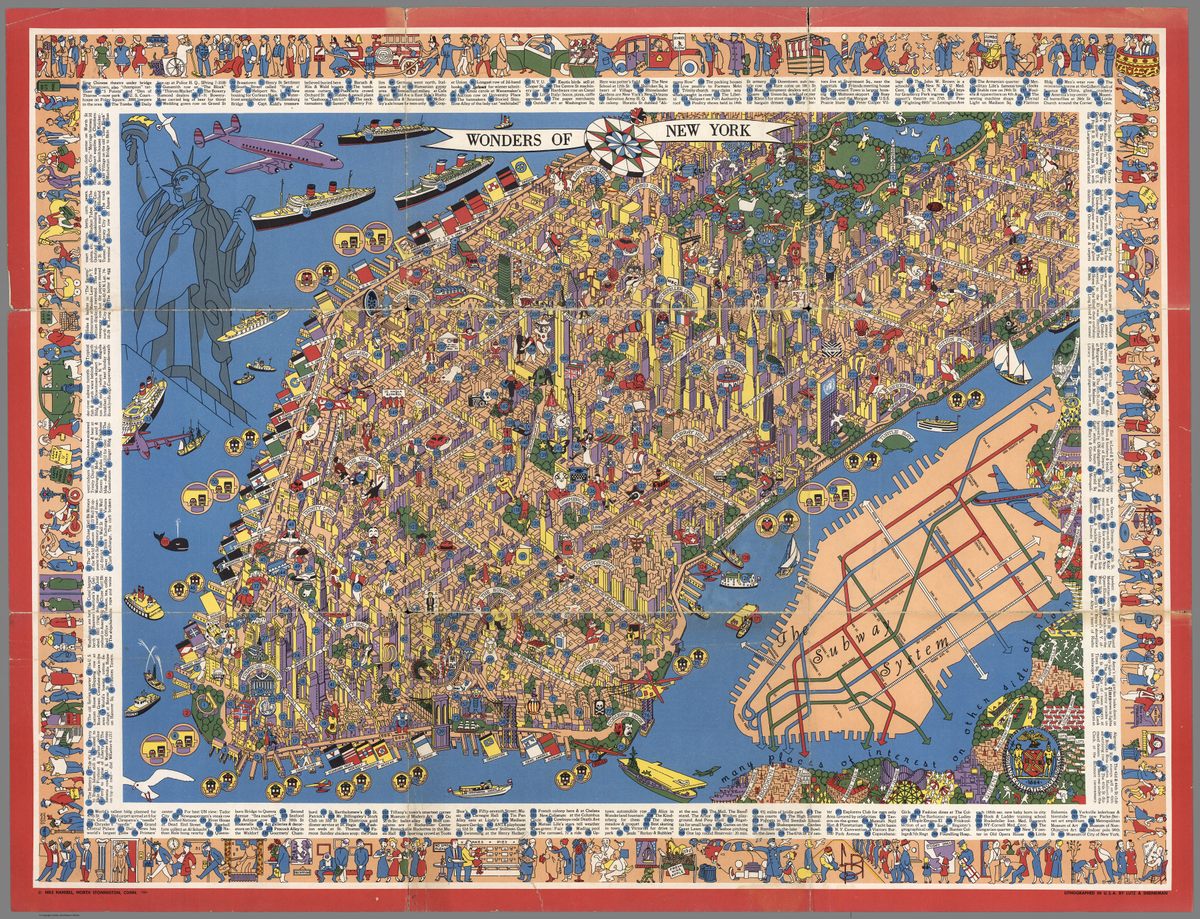

Step Into a Midcentury Map of New York, Packed With Weird Local Lore

Dragons, flea circuses, mermaids, and more wonders of the city.

There’s an old game in which someone throws a dart at a map, and then dreams of traveling wherever it lands. If you happened to find yourself in Manhattan in the early 1950s with a wide-open afternoon, you could have tried the same thing with this dense, boisterously illustrated map, and then ventured out to see the everyday wonders that awaited you there.

On the chart he titled “The Wonders of New York,” New Jersey–born cartographer Nils Hansell sketched out more than 300 diversions, from Manhattan’s southern tip up to 96th Street. The illustration now also graces the cover of the book Picturing America: The Golden Age of Pictorial Maps, by University of Maine geographer Stephen Hornsby. Inside, Hornsby makes the case that maps like this one—colorful, flamboyant, and not especially useful for navigation—were the offspring of the advertising culture that boomed in the mid-20th century.

In that vein, Hansell’s map is essentially selling the idea of Manhattan as the place to be. It captured the borough’s buzz, Hornsby writes, in the form of the “gleaming modernist skyscrapers and the new United Nations building, trans-Atlantic liners, and newly introduced jet passenger planes.” On a block-by-block level, though, those emblems take a back seat to the smaller sights that have always made the city deliciously, deliriously strange.

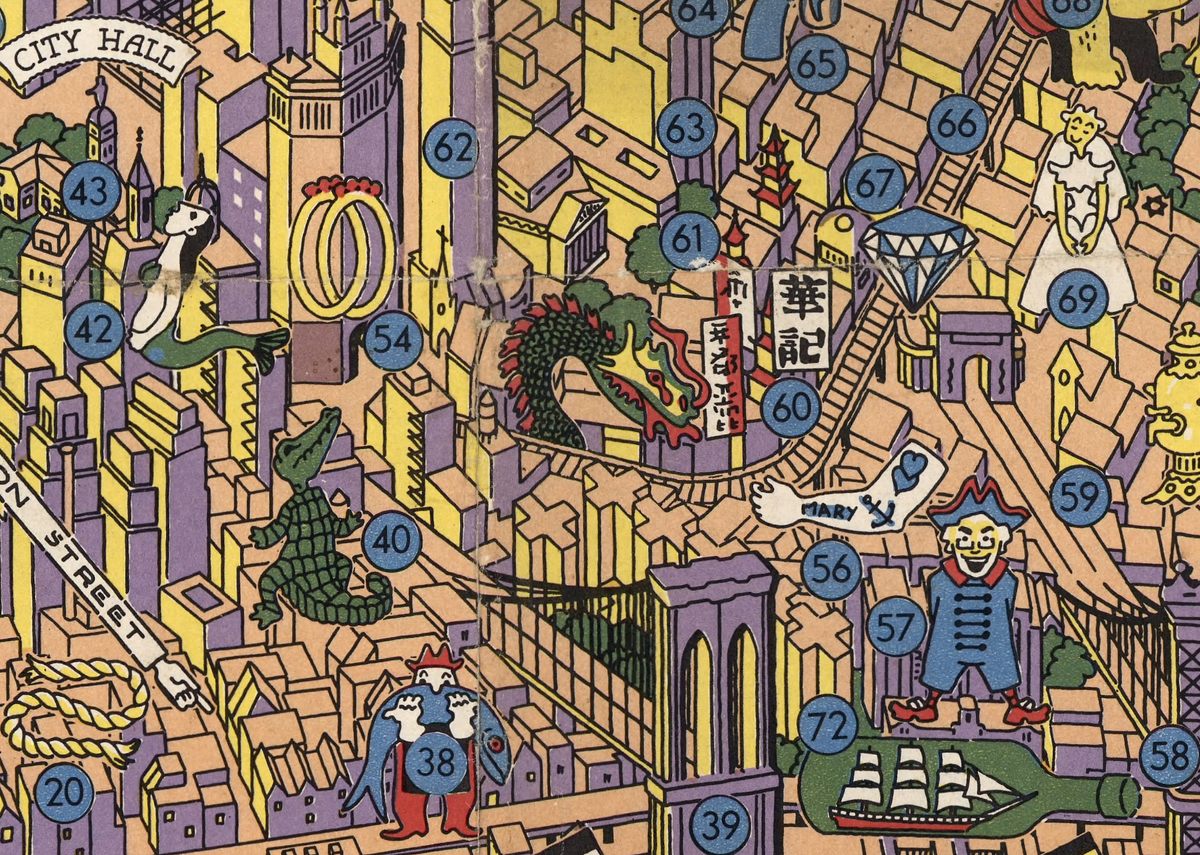

The map’s annotations read like an insider’s guide to Manhattan’s most rakish characters, showiest attractions, and least-plausible lore. Here be dragons (in Chinatown), and also prancing fleas, ships inside green glass bottles, and a nearly-nude opera singer hoisting a severed head on a platter. The flea marks the old site of Hubert’s Museum, a former Catholic school on West 42nd Street where, for nearly 40 years, visitors could watch Roy Heckler’s trained fleas pull off strange and strangely enchanting feats. (When prodded by Heckler’s tweezers, the fleas Petey and Peaches shimmied and waltzed, and a trio named Napoleon, Marcus, and Caesar hauled miniature cannons and chariots. “Not as exciting as a horse race,” Heckler once conceded, “but they get there just the same.”) Hansell also marked a building where all of the elevators were operated by redheads—or so he claimed—and near City Hall, a mermaid signals the place where P. T. Barnum once drew crowds with one of the mythical creatures’ “skeletons.”

Some of the spots were only accessible to men with fat pockets; others also extended an invitation to their glittering wives. Not everyone had the income or inclination, for example, to slurp the “famous Sunday chicken soup” at the Plaza, let alone strut around the Waldorf-Astoria’s Peacock Alley promenade, which was, The New York Times put it, “open to anyone who looked rich and powerful and wanted to display appropriate plumage.”

Other attractions were more democratic, and the map’s outer edges are littered little tips to help people make the most of their time. Anyone ambling around Central Park should note that a lap around the Reservoir takes 20 minutes, he wrote. He also declared that the park’s ice rink had “the best skating in town,” and that a stroll across the Brooklyn Bridge would make for the “best Sunday walk.”

At first read, a couple other notes on the dense margins seem to relate some pretty tall tales. Surprisingly, however, some of these head-scratchers have a grain of truth in them. For instance, a 1696 royal charter really did grant Lower Manhattan’s Trinity Church the right to dead whales that land along Manhattan’s shoreline. The document allowed church wardens and other officials to “seize upon and secure” the whales, and then “tow ashore and … cutt up the said Whales and try into Oyle and secure the Whalebone,” and funnel any profits back into the church. (“Trinity has never claimed a drift whale,” says the church’s archivist, Joseph Lapinski. “But I suppose the right to do so has never formally been rescinded.”) Other notes, like the one marking the spot where the pirate Captain Kidd was said to have squirreled away his loot, are a whole lot harder to fact-check without some shovels and a swashbuckler’s disregard for the law.

Several of the spots have disappeared over the years, so the map now feels like a relic. The 14th Street Armory, which also housed the annual Poultry Show, came down decades ago. The historic music row known as Tin Pan Alley has all but vanished. Gone are most of the typewriter repair shops, too, and while fishermen do still cast from piers around the city, bait-and-tackle shops are few and far between. You won’t find many pushcarts on Orchard Street anymore, but you will find a museum that chronicles the people who stocked them.

Still, even the busiest corners of New York City remain full of wonders, if you look closely enough—and, happily, some of them have gotten more accessible in the years since Hansell drew his grid. If you’re craving a quaff, McSorley’s Old Ale House now serves women. The artist placed the Explorers Club near Columbus Circle, but it has since trekked to the east side of Central Park and now also opens its rolls to adventurers with no regard to gender. The street grid may stay the same, but the world on top of it is constantly shifting. Whether New York has lost its fundamental weirdness, though, is still up for debate.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook