Do You Like Dialect Quizzes? You Have a French Bicyclist To Thank

How a 19th century “human transcribing machine” inspired generations of linguists.

A 1900s-era bicycle—Edmond Edmont’s tool of the trade. (Image: Public Domain)

Back in 2013, millions of Americans spent a few minutes clicking through this dialect survey. They threw their lots in with “crayfish” or “crawdad.” They marveled at the number of words for rubbernecking. At the end, they likely received their geographic diagnoses with pride. Despite coming out on December 20, this quiz was the New York Times’s top-trafficked story of that year.

A decade earlier, when linguist Bert Vaux wrote the questions that inspired the quiz, he was thinking about his dad, from New York, for whom “orange” is one syllable, and his mom, from Indiana, who pronounces the “law” in “lawyer.” He was thinking about cola, pop, and soda. He may have even been thinking about jawn, Philadelphia’s all-purpose noun. But he was also channeling a particular professional hero—a bicycling French surveyor named Edmond Edmont.

Long before we had viral quizzes to gather our peculiarities, there was only Edmont—a linguistic assistant who spent the end of the 19th century bicycling around France, speaking to locals, and cataloguing their unique words and phrases. Over four years, Edmont journeyed to over 600 towns, gathering material for what would become the Atlas Linguistique de la France: the world’s first great linguistic atlas.

A century later—after technological revolutions and scholarly schisms wholly reshaped the field—Edmont remains, in the words of one linguist, “a mythical figure in the history of dialect surveys.” Whether you’re the kind of surveyor who spends hours speaking to farmers in Georgia, or the kind who dreams up the Buzzfeed Accent Challenge, his work remains both vital and informative.

The University of Malburg, from which Wenker surveyed Gemany. (Image: Hydro/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Today, locals like to show off their sonic quirks. But for most of history, people weren’t nearly as concerned with how or why their speech patterns differed from their neighbors’. Everyone knew other people spoke differently—and some even noticed that these changes were specific to certain spots—but no attempt was made to study this phenomenon with any sort of rigor. It just was how it was.

As the 1800s wore on, though, the grid of science was applied to other disciplines: economics, meteorology, natural history. Eventually, a group of German linguists, called the Neogrammarians, decided to try laying it over language. In 1876, a PhD student named Georg Wenker drew up 42 sentences that, in his estimation, covered the most changeable aspects of the German language.

Over the next decade, Wenker mailed nearly 50,000 sentence sets out to schoolmasters around the country, with instructions to “translate” them into the local vernacular and send them back. By mapping how people from different places rendered statements like “In the wintertime dried leaves fly about in the air,” or “I will slap your ears with the cooking spoon, you monkey!,” he could trace each word and sound’s place-specific evolution.

The reality was much messier—Wenker’s results were so varied and illogical, they ended up disproving the Neogrammarian’s theories about how words worked—but he had done something vital: he had pulled off the first mail-order dialect survey.

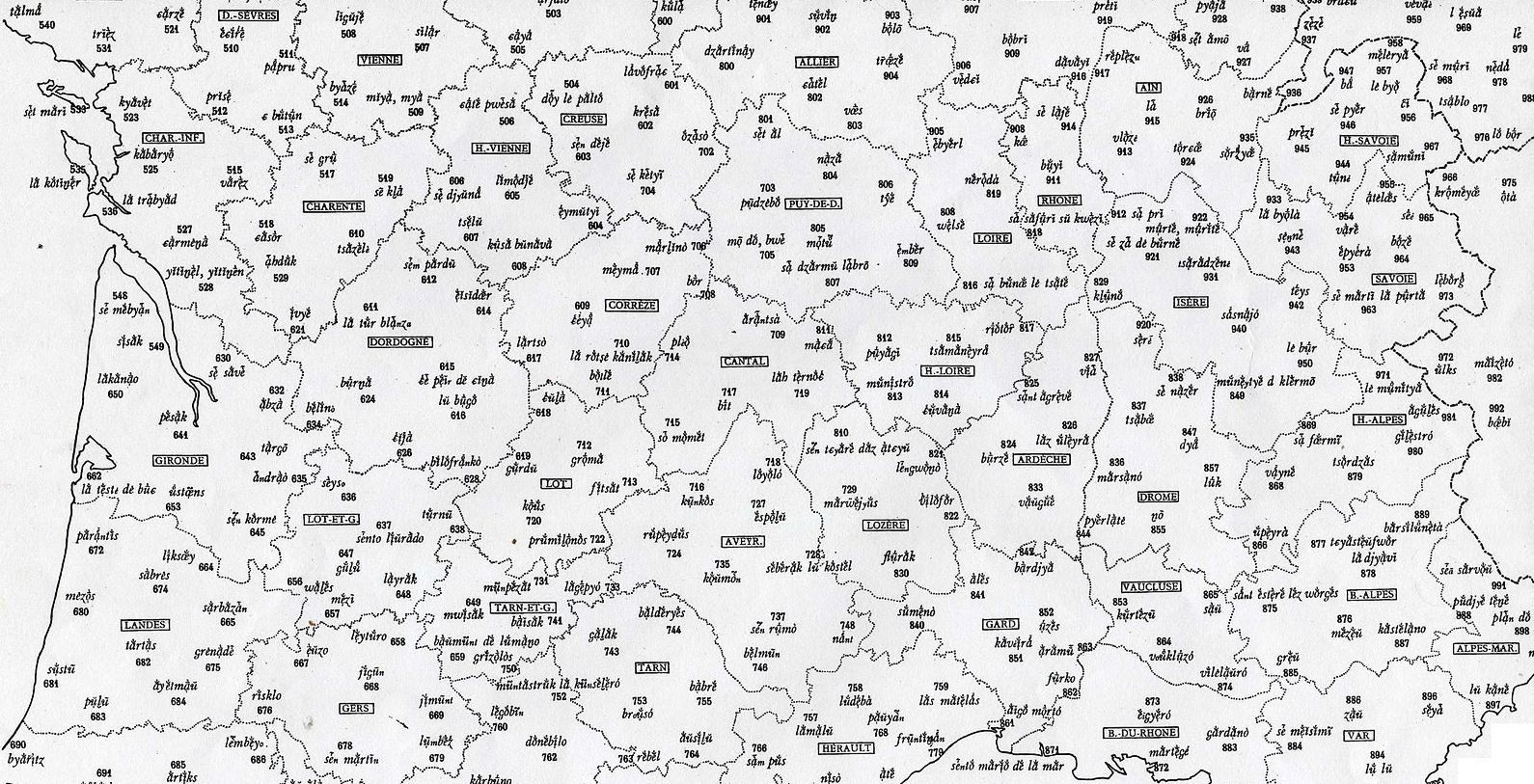

A page from the Atlas Linguistique de la France, mapping pronunciations onto localities. (Image: Jules Gilliéron/Public Domain)

One linguist, a French professor named Jules Gilliéron, decided he could improve on Wenker’s work. In 1896, he drew up his own set of 2,000 common words and phrases, similarly designed to cover a broad swath of French. Taking notes from Wenker’s failures, he eschewed the translation method in favor of elicitation: rather than stuffing chosen words and phrases into sentences, he designed questions that would inspire his research subjects to say them naturally. This way, he figured, he could avoid biasing his results before he even started.

But Gilliéron’s secret weapon wasn’t his strategic word-wrangling: it was Edmond Edmont, a man renowned for his keen hearing, his powers of observation, and, presumably, his strong legs. For the next four years, Edmont spent every day bicycling around France. He’d roll into town, find a volunteer, and spend hours going through Gilliéron’s questions. As the pair spoke, Edmont would scribble down answers in a phonetic shorthand. In all, Edmont visited 639 different points across the country. He was, in the words of one linguist, a “human transcribing machine.”

Edmont mailed his thousands of pages of notes back to Gilliéron, who gathered them into what would become the Atlas Linguistique de la France, published in installments between 1902 and 1910. While sifting through the hand-written pages, Gilliéron hit on the founding insight of dialectology. Rather than conforming to a set of general rules, he concluded, “every word has its own history.” The only way to trace a particular word’s past was to keep asking around.

People call this guy all kinds of different things. (Photo: Tony Hisgett/CC BY 2.0)

This mantra, and the Atlas Linguistique, birthed scores of imitators. Over the next century, dialectologists from Switzerland to Japan sent their own Edmonts from town to town, seeking volunteers, making them talk, and noting down their every hard vowel and phrasal habit. For Americans, always trying to figure out where they really came from, the method held particular appeal.

In the late 1920s, linguist Hans Kurath ordered teams of helpers around the United States, where they asked every farmer they met to name the parts of a plow and demonstrate how they called in their cows. Kurath’s teams came out convinced that there were three types of American English—North, Midland, and South—each traceable to the different areas of Britain that had colonized them. Midway through the 1960s, professor Fred Cassidy sent 800 graduate students around the country in vans he called “Word Wagons,” each wielding a 1,600-part questionnaire. Cassidy and company came out with the Dictionary of American Regional English.

Around this time, though, dialectology underwent a massive shift. Linguists like William Labov began arguing that geographically large samples were less important than demographically representative ones, and a schism appeared between the old style and the new. “The whole world of what was valuable and what wasn’t changed in the 60s,” Vaux says. “Since then, large-scale surveys have been profoundly out of fashion.”

In 2002, when Vaux put together the Harvard Dialect Survey—a subset of which eventually inspired the New York Times quiz, along with countless other linguistic lists and heat maps—he had these pre-schism days in mind. “I loved the idea of trying to comprehensively cover a physical space the way they did with the French survey, and I also liked the idea of exhaustively covering a language.”

He didn’t have a tireless biker, but he did have the Internet. With the help of a student at CalTech, he rigged his survey so that it showed respondents a real-time geographic heat map, based on data from just one question. People loved seeing their linguistic allegiances charted out. His initial survey received 60,000 responses.

Vaux does not ascribe to regionalism, exactly, instead believing that ”every individual human is different linguistically.” No matter where they are from, they’ve been privy to diverse influences. “I want to know what every one of them says, ideally.” The way to do this, he thinks, is combining new-school tech with old-school scope.

Is it crawfish, crayfish or crawdad?!?! Seems like this map helps solve the debate based on geography. pic.twitter.com/N7KRfnT5nj

— Apollo Mapping (@ApolloMapping) February 23, 2015

Those who prefer the opposite technique—in-person surveys of representative samples—are feeling the march of progress in a different way. The leisurely, six-hour guided conversation, for instance, has gone the way of the long-distance bicycle commute. “In the 1930s and 40s, you could get someone to sit down for that long and answer questions for you,” says Bill Kretzschmar, editor in chief of the Linguistic Atlas Project. “But who’s going to do that now?” In recent decades, project organizers have cut the questionnaire in half, and then in half again, “to deal with the pace of life.”

Vaux, meanwhile, is currently working on a survey to tease out the differences in international English dialects. ”My way of thinking is very much in the minority among professional linguists at the moment,” he says. “But I think it’s highly likely that the online type [of survey] will predominate for the foreseeable future.”

If you want to reach a lot of people in a short span of time, the Internet beats even a bicycle.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook