Eat Like an Ancient Greek Philosopher

Before attending third-century dinner parties, readers consulted this “marvelous feast of words.”

You’ve just been invited to a dinner party in third-century Rome. It’s going to be a swanky affair with high-profile guests, and you’re determined to make a good impression. You’ve figured out your outfit and you’ve packed your spoon and napkin (Roman hosts did not provide these). There’s just one part of the evening that concerns you: conversation.

The other guests will be well-traveled and well-read, especially in the Greek literature popular with Roman elites. What if you don’t get their references? What if you can’t think of anything clever to say, and you never get invited to another dinner? After a moment’s panic, you breathe a sigh of relief and head for your library. Your social success is assured; you’ve just remembered that you own a copy of Deipnosophistae.

Written in Greek around the year 200, the name of this text has been translated a number of ways. Professor S. Douglas Olson of the University of Minnesota, editor of an English edition of Deipnosophistae, prefers The Learned Banqueters. “It’s a weird phrase,” Olson says, “but I think it’s suggestive enough of what the work actually does.” Dr. Adam Cody, a professor of humanities at the Virginia Military Institute who wrote his dissertation on Deipnosophistae, offers Banquet Wits. Cody suggests this because it sounds like Banquet Twits, which hints at the work’s lighthearted tone. “These are people who are serious,” Cody says of the ancient banqueters, “but perhaps not to be taken seriously.”

Deipnosophistae is presented as a series of letters written by the author, Athenaeus, describing dinner parties Athenaeus attended at a wealthy man’s villa in Rome. These sumptuous affairs are highly fictionalized. The guests are a mix of historical figures, contemporaries, and invented characters, and their dialogue is written like informational articles, complete with citations. Each dish brought to the table inspires the diners to quote references from every genre of Greek literature. Deipnosophistae “will tell you how to cook oysters,” Cody says, “but it’ll also tell you all the lines of poetry that you should recite when the oyster course comes out.” For more obscure delicacies, there might be just one or two references. For figs, a common staple, Athenaeus pulls quotes from over 50 authors. In all, Deipnosophistae quotes from around 2,500 sources, drawn from hundreds of authors dating back centuries.

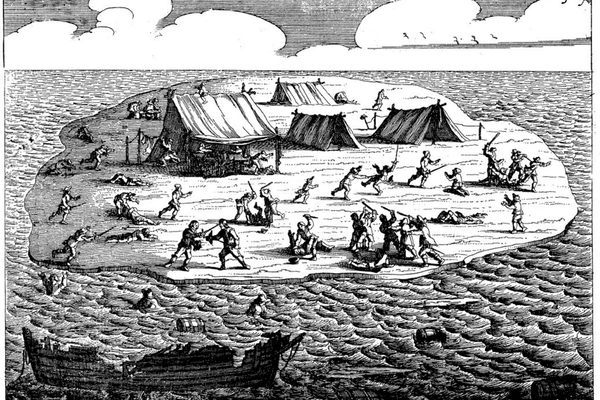

Sometimes, these quote-fests devolve humorously into debate as the learned banqueters shout over each other, slinging insults and quoting authors with opposing views. “It’s not one person talking, it’s this cacophony,” says Olson. Deipnosophistae contains the oldest-known Greek recipe, for a grilled fish sprinkled with grated cheese, but also quotes the opinionated food critic Archestratus, who said that cheese “makes a mess” of good-quality seafood. Olson compares Deipnosophistae to a food magazine that covers many stories and perspectives, allowing the reader to choose what to read according to their interest. “You don’t read a magazine about food for a single point of view, right?” he says. “And some of the articles you think are great. And some you think, ‘You know, I’m not actually even interested at all.’”

The 17th-century English scholar Thomas Browne wrote that Athenaeus added topics to Deipnosophistae like a chef adding seasoning, so that the work contains “some spice or sprinkling of all Learning.” Topics covered in Deipnosophistae range from early science experiments to children’s songs to a list of the third century’s hottest dance moves (sadly undescribed). But Athenaeus’s chief interest is the food of the Greek world, which he meticulously documents with catalogs of drinking vessels, desserts, vegetables, and fish species. Athenaeus also compares dining customs in different Greek cities and other parts of the Roman Empire, and records recipes from the Classical Age seven centuries earlier, when Greek culinary culture, in his opinion, reached its greatest heights. In Classical-era Sybaris, a Greek city in southern Italy known for haute cuisine, Athenaeus reports that “if any confectioner or cook invented any peculiar and excellent dish, no other artist was allowed to make this for a year.” This is considered the first recorded example of intellectual property law.

Even as the master chefs of Sybaris were patenting their recipes, Classical Greek philosophers debated whether cooking should be considered a tekhne, which means “skilled craft” or “art,” or a mere empereia, which might be translated as “knack.” Athenaeus mostly presents himself as a neutral recorder of the words of others, but he hints at his own opinion on cooking with some of the quotes he chooses to use. One of Deipnosophistae’s most-famous passages tells of a king who developed a craving for anchovies while far from the sea. His royal chef prepared a substitute by carving slivers of turnip into tiny fish and frying them with salt and poppyseeds. Delighted by the chef’s ingenuity, the king exclaimed, “the cook and the poet are alike: the art of each lies in his mind!”

Cody reads this as a direct refutation of “one of Plato’s signature arguments:” that cooking is not an art form. Instead, it’s “just a way of gratifying people’s pleasures. And it’s a way of disguising the reality of what you’re dealing with,” he says. Plato used cooking as a metaphor for deception, because chefs conceals raw ingredients by transforming them. By choosing to include the story of the turnip fish in Deipnosophistae, Cody explains, “Athenaeus is saying that actually, the cook is not in the job of deception, because isn’t the job opening people’s eyes to new possibilities?”

Deipnosophistae owes its framing device to Plato’s Symposium and other Classical philosophy written as dinner table dialogue, with essays presented as speech. However, Athenaeus does something new with this established format. Cody describes the structure of Deipnosophistae as “a fusion of two traditions.” One is the philosophical dinner debate, but the other is what Cody calls “knowledge writing:” informational text similar to modern encyclopedias. Athenaeus is “trying to offer a window into the wide world,” says Cody. What the chef and the poet have in common is that they can lead their audience, in Cody’s words, “to perceive things in a new way.” Perhaps Athenaeus admired cooking because he recognized in it a parallel to his own writing, in which quotes are selected and combined, as carefully as ingredients in a recipe, to transform into a harmonious final result.

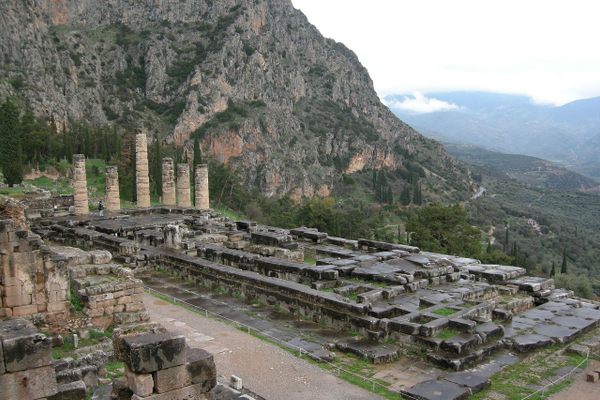

Athenaeus was born in Egypt, then a Roman province after centuries of Greek rule. In third-century Egypt, the days of the Greek pharaohs were long gone. But the Library of Alexandria still housed a treasure trove of Greek literature, which provided many of the quotes used in Deipnosophistae. Olson explains that although the library’s collections had become “old-fashioned and obscure” by Athenaeus’s time, they still held “huge intellectual interest” for Greek and Roman scholars. Olson places Athenaeus alongside other Greek authors of the third century who aimed to display “the Greek contribution to the world.” Even if they did not focus on food, they were “casting about for what it means to be Greek, in this world where being Greek is no longer important in some sense,” because of the political dominance of Rome.

In many cases, all we have left of an original Greek source is whatever scrap Athenaeus chose to quote from it. Both Olson and Cody first encountered Deipnosophistae the way that many scholars of Classical literature do: they were researching a specific topic in Greek writing, unrelated to food, and came across quotes from other sources on that topic cited by Athenaeus. Picture Deipnosophistae as an online article, filled with hyperlinks that lead to dead webpages.

In Cody’s view, Athenaeus also embedded an internal “mental hyperlinking system” into Deipnosophistae, providing the rambling work with a kind of index. Even if the conversation wanders, the dinners themselves unfold according to a pattern that third-century readers would recognize. The courses of each menu, Cody explains, “provide an organizing arrangement for the information … so if you want to look up the literary quotations about oysters, all you need to do is think, ‘Well, where do oysters come in the sequence of a banquet? Okay, so it’s an appetizer. So I look at the beginning.’” He compares this with the Ancient Greek memory palace technique, in which visualizing a physical space is used to help recall information.

Cody describes Deipnosophistae as a “cheat book” for appearing “witty and sophisticated.” He suggests that an ancient reader might have used the courses of the banquets described within to memorize some of the highlights of Greek literature, to “seem like an educated, charming dinner table companion.” For Olson, Athenaeus’s main goal was simply to document the Greek culture that most interested him by compiling sources in an engaging way. “I’m kind of resistant to the idea that it’s a text that needs or wants a single approach, or offers a single argument,” Olson says.

Deipnosophistae is a work that defies easy classification. It belongs to the canon of food writing, but goes well beyond food in its scope, and in its importance to our modern understanding of the Ancient Greeks. Olson calls Deipnosophistae “a banquet of texts,” echoing Athenaeus’s own description of his work as “a marvelous feast of words.” The real “meal” in Deipnosophistae, Olson says, is not the dinner eaten by the characters. Instead, it’s “this endless series of platters of works of literature that are being served up to you.”

As you might sample different dishes according to your fancy at a buffet, so you’re meant to graze on Classical Greek culture in the pages of Deipnosophistae. The Library of Alexandria and the cookbooks of Sybaris may be lost, but at least a few traces of them have survived, thanks to Athenaeus.

Ancient Greek Grilled Fish with Cheese

Adapted from Deipnosophistae by Athenaeus, written in the 3rd century

- Prep time: 10 minutes

- Cook time: 20 minutes

- Total time: 30 minutes

- 2 servings

Ingredients

- 1 whole mackerel (about 12 - 18 inches), or 2 unsalted mackerel fillets

- 2 tablespoons good-quality olive oil, plus more for topping

- About 1/3 of a cup grated hard, salty cheese, preferably sheep’s milk, such as Italian pecorino Romano or Greek kefalograviera

- 2 tablespoons wine vinegar (white or red)

- 1/2 teaspoon dried marjoram or oregano

- 1/4 teaspoon powdered asafetida (Available at South Asian grocery stores, this oniony spice substitutes for extinct silphium or laser, which Archestratus complained was overused in fish recipes)

- Fish sauce or salt to taste

Instructions

-

Lay fish flat in a baking dish lined with parchment paper.

-

Rub fish with olive oil on both sides.

-

Sprinkle grated cheese over fish.

-

Bake fish at 400°F for 20 minutes. When the fish is done, the eyes will turn white and the flesh will be easily separated with a fork.

-

Remove fish from the oven and allow it to rest for a few minutes.

-

Top fish with more olive oil.

- Sprinkle fish with wine vinegar, marjoram, salt or fish sauce, and asafetida.

Notes and Tips

In Deipnosophistae, Athenaeus records several recipes for fish baked or grilled with a grated cheese topping, a specialty of Classical-era Greek cities in southern Italy. One of these, from a lost fifth-century BC cookbook by a Sicilian chef named Mithaecus, is the oldest-known recipe in Greek, and the earliest recipe by a named author.

Mithaecus put cheese on the eel-like ribbonfish; other known recipes used cheese for parrotfish, wolf-fish, or mackerel, which is the only one of these fish to be widely available today. Caraway seed is another seasoning found in some of these recipes.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook