Why Voltaire Drank Bull’s Blood

Bull’s blood isn’t poisonous; so why did people think it was for centuries?

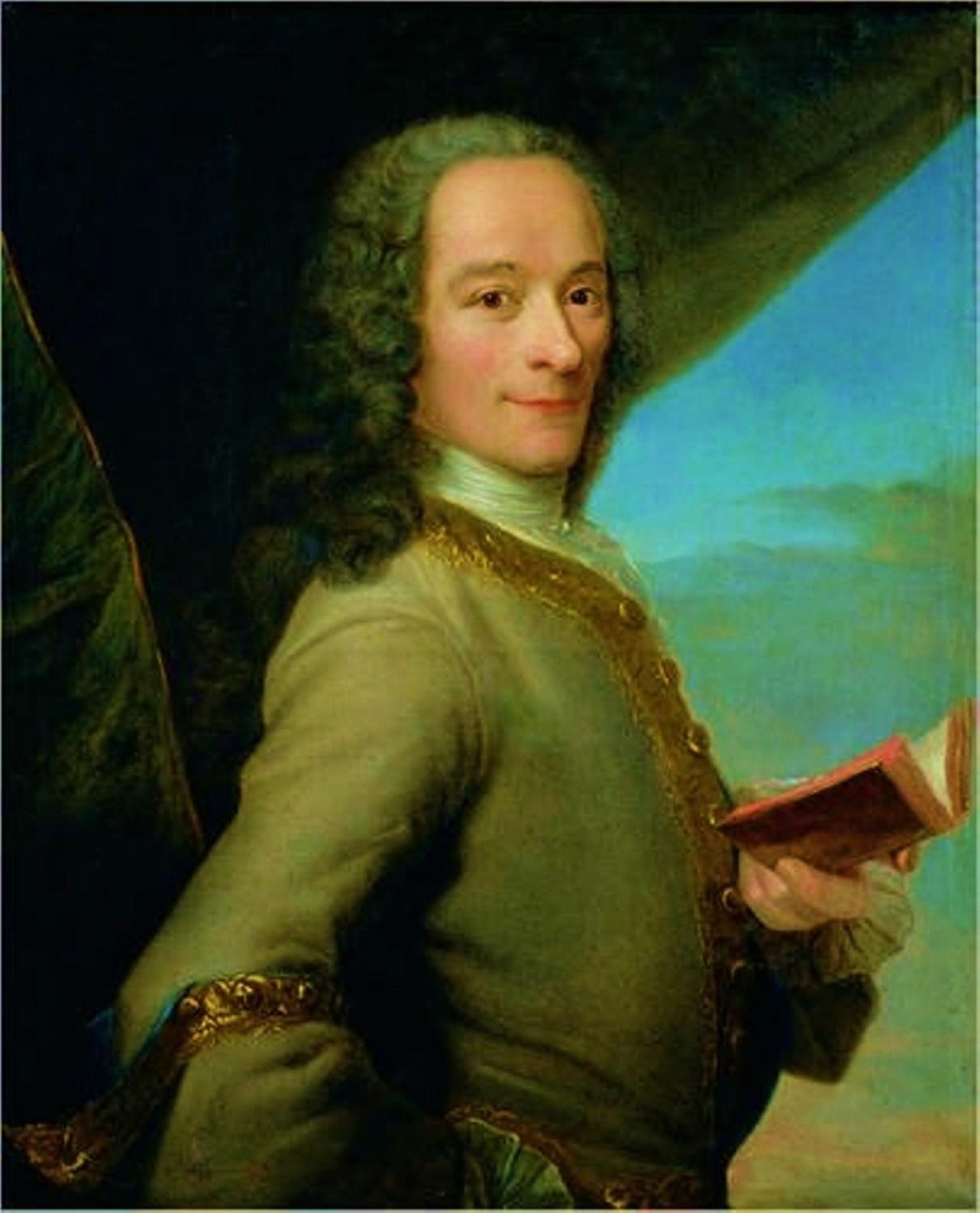

The 18th-century French writer Voltaire is remembered for his witty satire and social critique. Less well-known is the time he drank fresh bull’s blood for science. As described in his Philosophical Dictionary in 1764, Voltaire conducted this peculiar experiment to dispel an equally strange, yet persistent, myth dating back to ancient times: that bull’s blood was a deadly poison.

“If a man in his folly tastes the fresh blood of a bull, he falls heavily to the ground in distress, over-mastered by pain,” the Greek physician Nicander wrote in the second century BC. Nicander was echoing earlier Greek writers like Aristotle, who described bull’s blood as the “quickest to coagulate” of all animal bloods (a claim unsupported by modern research, which has found that the blood of cattle clots more slowly on average than that of some other animals such as pigs and sheep). However, Ancient Greek scholars believed that bull’s blood solidified rapidly in the throat when swallowed, causing fatal asphyxiation. “The blood congeals easily,” Nicander explained, “and, in the hollow of [the victim’s] stomach, clots; the passages are stopped, the breath is straitened within his clogged throat, while, often struggling in convulsions on the ground, he gasps bespattered with foam.” To treat this gruesome condition, Nicander recommended several remedies, of which some (fresh figs in vinegar) sound easier to obtain than others (the milk of a hare or deer).

Greek and Roman scholars repeated these claims about bull’s blood as fact for centuries. Some attempted a scientific explanation, like Pliny the Elder in the first century, who suggested that the braver and fiercer the animal, the faster its blood coagulates. Bull’s blood was the alleged suicide weapon of mythical characters like King Midas, as well as real historical figures like the Greek commander Themistocles, who was said to have drunk bull’s blood rather than follow orders from the King of Persia to lead an army against his fellow Greeks.

“I was so lulled by those tales during my childhood that, in the end, I made one of my bulls bleed,” Voltaire wrote in his Dictionary, in a chapter on the natural history of poisons. He expressed skepticism of the ancient claims, pointing out that people in the French countryside “swallow beef’s blood every day” in blood sausage and other dishes. Although Voltaire didn’t say whether the fresh blood was difficult to stomach, or how much he actually consumed, he confirmed that he did not fall writhing and choking to the ground. Referencing a historical account of the Central Asian Tatars drinking horse blood, Voltaire wrote that bull’s blood “did no more harm to me than horse blood did to the Tatars, or blood sausage does to us every day—especially when it’s not too fatty.”

Voltaire satisfied his own conviction that bull’s blood wasn’t deadly. But why did anyone believe it was in the first place? In 1993, Classics scholar Kenneth Kitchell put forth an intriguing theory in a paper called “Death by Bull’s Blood: A Natural Explanation.” Kitchell pointed out that fresh bull’s blood was drunk in some ancient religious rituals, and modern peoples like the Maasai of East Africa consume it as a nourishing staple. The Maasai believe that cow’s blood confers a variety of health benefits; in the early modern United States, fresh cow’s blood was also formerly believed to be a cure for consumption (tuberculosis). Modern hand-wringing over the health risks of consuming animal blood generally focuses on blood-borne illness, not any inherent toxicity of the blood itself. As a result, Kitchell wrote, “we must find a reason—a natural and probable reason—why the ancients would believe a story so easily disproved.”

Kitchell noted that almost all the famous deaths attributed to bull’s blood, including those of Midas and Themistocles, “are located in the East in general and show a special affinity for Persia.” The Ancient Greeks associated Persia with advanced knowledge of poisons, which mostly came from plants. And metaphorical names for plants were just as common in ancient times as they are today. Could “bull’s blood” originally have been the name of a poisonous plant that was later taken literally?

Using Nicander’s account of the symptoms of bull’s blood poisoning, Kitchell reviewed the possible suspects. The description of bull’s blood clotting in the throat might be a mistaken account of the victim coughing up clots of their own blood, which can be induced by some poisonous plants. Because bull’s blood is used for suicide in ancient literature, but not murder, Kitchell inferred that it was a difficult poison to conceal in food or drink, perhaps because it had a strong flavor. The name might indicate a dark red color and possibly a specific danger to cattle, as some poisonous plants are infamous for harming livestock that graze on them. Kitchell identified three plants that fit his criteria: tansy, black hellebore, and cowbane (the latter named for its tendency to kill cattle). “But even if the exact plant or plants remain unknown,” Kitchell wrote, “the strong likelihood remains that ‘bull’s blood’ is to be identified as the Eastern, probably Persian, name of a plant-based poison, perhaps red in color, of bitter taste, used almost exclusively for suicides in the East.”

Another theory suggests that the “bull’s blood” that killed Themistocles didn’t come from an animal or a plant. Realgar, or arsenic sulfide, is a red crystalline mineral that was used for a variety of purposes in ancient times, including red paint and cosmetics. It’s also highly toxic, and some authors have noted similarities between Nicander’s description of the effects of bull’s blood and those of arsenic poisoning. Realgar even has a connection to Persia: Sandaráke, the Ancient Greek name for realgar, was also the name of a city in the former Persian Empire (modern Turkey).

It’s possible that “bull’s blood” was originally a nickname for realgar or a plant-based poison that later authors misinterpreted. Similar confusion has occurred with other names across the centuries. The medieval Arabic term mumiya, which originally referred to a medicinal mineral, is believed to have led to the craze for remedies made with literal powdered human mummies in early modern Europe. Ancient medical writers often repeated the words of earlier sources uncritically, leading them to mix fact with fiction. E. A. Barber, a 20th-century Classicist, described Nicander’s work as containing “absurd errors due to popular superstition alongside exact descriptions of plants and medical prescriptions so detailed and precise that the remedy could be made up today.”

That the myth of bull’s blood being poisonous persisted for so long serves as a reminder to always check the trustworthiness of one’s sources. Unless you happen to be as bold as Voltaire, who decided to test the outrageous claim on himself. We may never know exactly what the original “bull’s blood” was, but one thing at least is clear. As Voltaire wrote after downing his grisly beverage: “Be certain, dear reader, that Themistoceles did not die from it.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook