Before Edward Lear Was a Limerick Genius, He Was a Teenage Parrot-Painting Prodigy

The beloved children’s poet spent his own youth “at the West End / painting the best end / of some vast Parrots / as red as new carrots.”

Edward Lear was a man unafraid of his own imagination. In his best-known nonsense poems and limericks, he wrote of things the world has never seen: green-headed Jumblies; toeless Pobbles; oceanic romances between birds and cats.

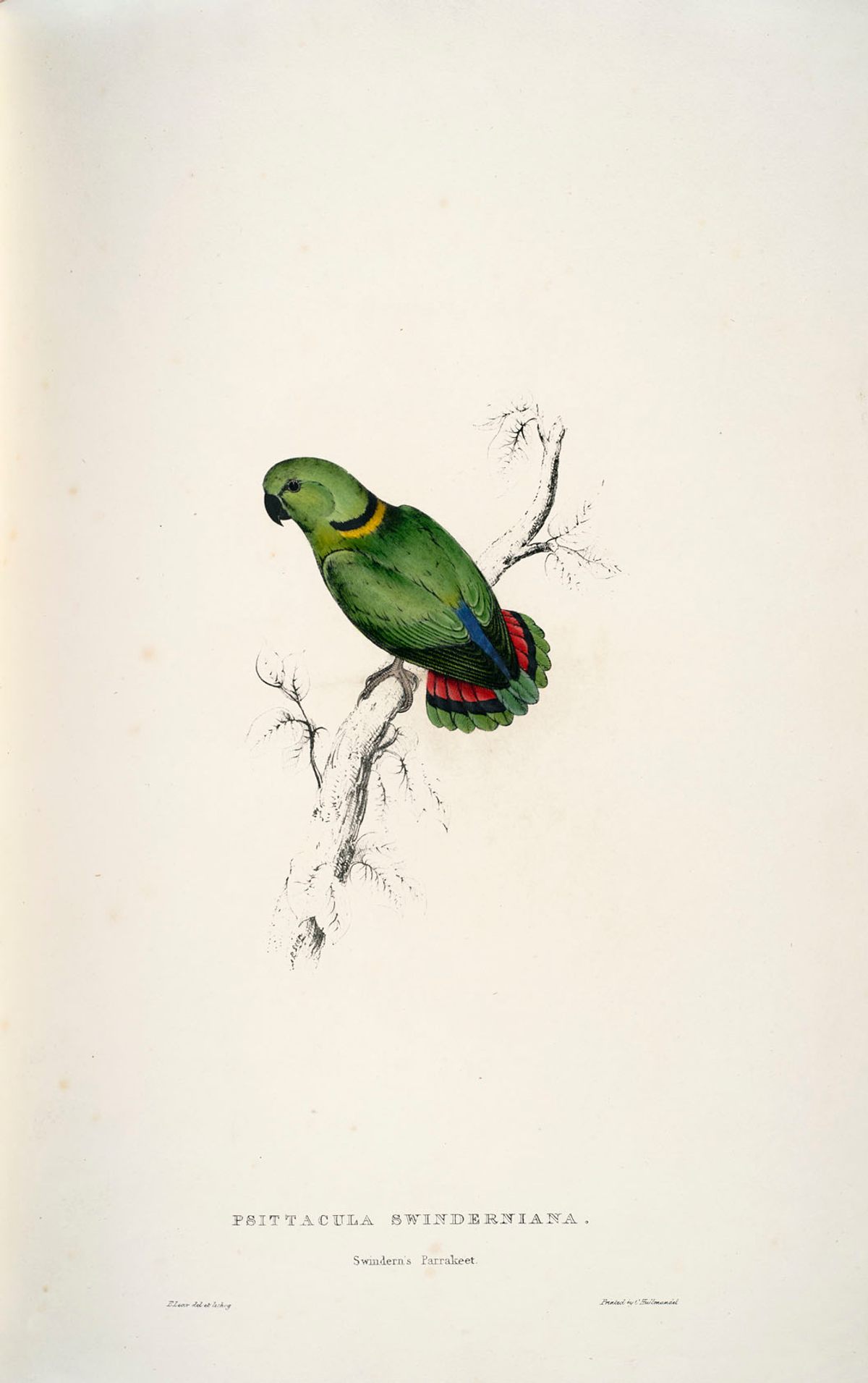

But before he began bringing these impossibilities to life, Lear had a different focus: he drew parrots. When he was young, Lear was employed as an ornithological illustrator, and he spent years learning to draw birds, favoring live models in an era when most worked from taxidermy. Before he turned 20, he’d published Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots, a critical success, and the first monograph produced in England to focus on a single family of birds.

Lear was born in London in 1812. One of the youngest of a gaggle of kids—he always said he was the 20th of 21, although some contest this exact number—he was raised mostly by his oldest sister, Ann. According to biographer Peter Levi, it was Ann who taught Lear to draw, and the two siblings spent many hours meticulously copying flowers, birds, and butterflies from textbooks and magazines.

Early on in Lear’s childhood, his father went into debt, and his family fell on hard times. When he turned 15, he decided to put his talents to work professionally, and began taking commissions for everything from decorative fans to “morbid disease drawings for hospitals,” as he later wrote a friend. In this way, he explained, he managed to make enough money “for bread and cheese.”

But when he found the time to choose his own subjects, he often made his way to London’s Zoological Gardens. A relatively new experiment by the city’s Zoological Society, the Gardens were dedicated to scientific study, and were filled with creatures imported from all corners of the British Empire. While many artists of the time relied on taxidermied specimens—which, after all, were better at staying still—Lear preferred drawing live animals, and was known to occasionally enter their cages, so as to get a better look.

Although the Gardens were closed to the public, Lear somehow wrangled an invitation to go inside and sketch. (Some sources say that the president of the Zoological Society, Edward Smith-Stanley, happened to come upon Lear drawing and was so impressed that he signed a permission slip. Others say the young artist simply managed to pull some strings.)

Lear liked all kinds of animals, and tried his hand at drawing many, from kangaroos to weasels to platypuses. But although mammals provided a welcome challenge, he found himself especially adept at birds. The zoo’s aviaries were still being built, and Lear quickly gained admission to the temporary parrot quarters on Bruton Street, home to everything from a green macaw to a black-masked Mascarene. “Parrots are my favourites,” he would write later, “and I can do them with greater facility than any other class of animal.”

Perhaps for this reason, in between commissions, Lear decided to undertake a larger project: he would, he decided, create a set of prints devoted entirely to parrots. This was a unique idea, as most natural history books at the time took a geographical focus rather than a taxonomic one, as with John James Audubon’s The Birds of America. Lear managed to gather 125 subscribers—including the then-Queen Consort, Adelaide, to whom he eventually dedicated the book—and set to work.

Lear’s models inspired at least one bit of verse. In December of 1830, he ended a letter to a friend with an account of a parrot-filled day that had left him rather peckish:

“Now I go to my dinner,

For all day I’ve been a-

way at the West End,

Painting the best end

Of some vast Parrots

As red as new carrots,—

(They are at the museum,—

When you come you shall see ‘em,—)

I do the head and neck first;

—And ever since breakfast,

I’ve had one bun merely!

So—yours quite sincerely.”

As this poem suggests, the job was rather demanding. Although Lear worked in many different media—his papers are full of ink, graphite, and watercolor sketches—the 42 works that make up Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae are lithographs, at the time a fairly new style of art, and one that required many detailed steps in order to produce a proper print. It apparently took Lear a little while to figure it all out: one early draft of a purple-naped lory is captioned “my first lithographic failure.”

Eventually, though, he boiled the process down to a science. First, Levi writes, “A young zookeeper would hold the bird while Lear measured it in various directions.” Then Lear would make a few pencil drawings of the parrot, in different poses, doing his best to ignore the curious public (although sometimes he drew them, too).

Next, he’d choose his favorite drawing, and create two different versions: one in black and white, which he then copied directly onto the limestone printing slab, and one in watercolor, which he sent to a team of professional colorists so that they could replicate his work exactly.

Lear put out his lithographs in small batches. They were a hit from the beginning: after the release of the first two plates, Lear was inducted into the Linnaean Society, an honor he eventually celebrated on the title page of the book.

He also drew several favorable comparisons to Audubon, the premiere ornithological illustrator of the time. Critics called Lear’s birds “equal [to Audubon’s]… for grace of design, perspective, or anatomical accuracy” as well as “infinitely superior in softness.” (Audubon, who may or may not have agreed, did deign to buy a copy of the young upstart’s book.)

His sudden renown also granted him access to yet more parrots. “He went bird-chasing,” writes Levi, listing trips to aviaries, collectors, and commercial bird-dealers. He worked with stuffed specimens when no live ones were available, and labored over a sick bird’s strangely angled feathers. During a visit to the Irish ornithologist N.A. Vigors, he covered a draft with carefully mixed blotches of green, blue, and gray before finally coloring in a grey-cheeked parakeet.

By 1831, he and Ann had moved houses to be closer to the Zoo; the next year, he put out what would be his final batch of parrot lithographs, drew up a table of contents, and encouraged his subscribers to bind them into a complete book. He was 19 years old.

Although he started out expecting to produce 14 sets of illustrations, depicting about 50 species, Lear ended up stopping just short, at 42 prints total. In a letter to one of his subscribers, he cited two things that made him quit: first, he was building his brand but not his billfold, and second, he didn’t want to make the same mistakes as his father. “To pay colourer and printer monthly I am obstinately prepossessed,” he explained, “[and] I had rather be at the bottom of the River Thames than be one week in debt.”

And so he returned to commissions. The naturalist John Gould, a fan and patron, bought all the unsold copies of the parrot prints, and hired Lear to help with several monographs. Stanley, the president of the Zoological Society, paid Lear to sketch his entire at-home menagerie.

He drew ducks for one book, and pigeons for another, but when he was given the choice, he remained loyal to the stranger birds. “Lear drew the monstrous, the sinister and the eccentric; the heron, the owls, the black stork and the sympathetic flamingo,” Levi writes of Lear’s participation in Gould’s Birds of Europe. “The queerer the animal the more it arrested him.”

By 1837, when he was 25, Lear had moved on from scientific illustration altogether, and had begun traveling around Europe painting landscapes. Nine years after that, he published his first collection of limericks, A Book of Nonsense, which would shape the rest of his career. (He eventually gave up fine art, blaming his worsening eyesight.) But he never forgot his first avian love, which would show up repeatedly in his poems, fighting over cherries, dispensing wise advice, and doing pretty much everything but sitting still.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook