A Curious Menagerie of Mutant Taxidermy

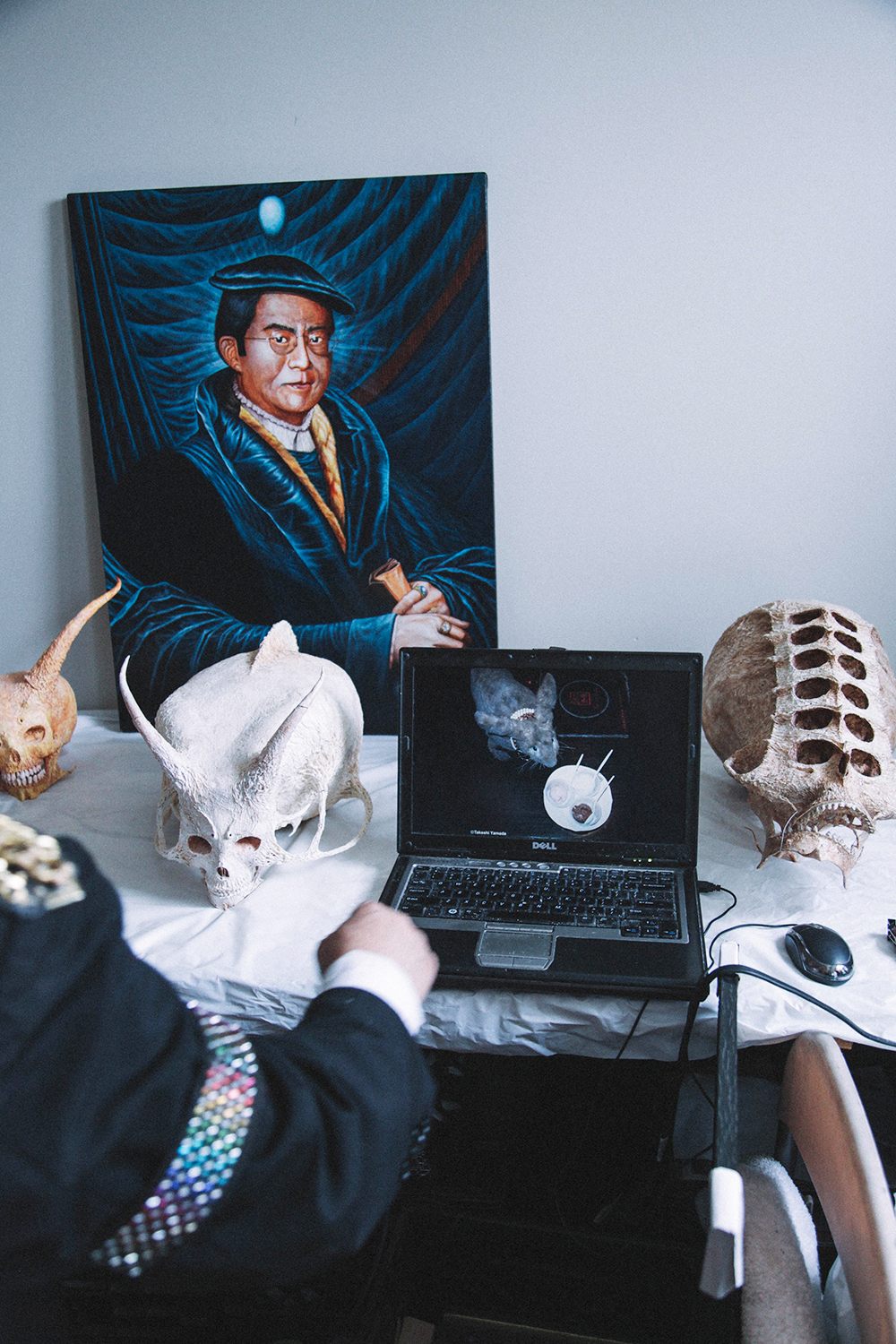

In a cramped apartment in East New York, the artist Takeshi Yamada lives among his strange creations.

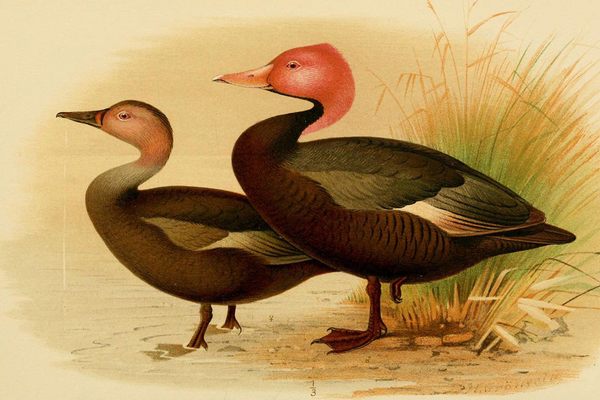

If you’ve spent much time in Coney Island, New York, you may have heard of the sea rabbit—a mythical beast of fabled origins that is one part rabbit, one part duck, and one part seal. The creature has become something of a local legend along the New York boardwalk, where she can often be found roaming alongside her creator, the self-described “rogue taxidermist” Takeshi Yamada.

“Seara,” as the creature is called, has joined Yamada on his day-to-day outings for nearly 12 years, and the age is beginning to show in her matted fur coat and dull black eyes. Yamada says the idea of creating Seara came to him in a vision, when he found an old fur coat beside a dumpster. From the discarded coat and an admixture of faux animal parts Seara was born, and ever since, she’s regularly frequented the Coney Island waterfront, where Yamada chats and poses for photographs with curious beachgoers.

The pairs’ adventures are immortalized online. A quick Google search of the two yields hundreds of photos branded with Takeshi Yamada’s copyright: Yamada and Seara riding the subway. Yamada and Seara eating sushi. Yamada holding a bejeweled Seara on the beach, looking out sternly from beneath his black Fedora beside group after group of smiling, bikini-clad women. “The paparazzi,” Yamada explains.

“I don’t take Seara out, she takes me out,” says Yamada. Their excursions are often met with delight and curiosity. “When I work with Seara, I am invisible,” he says. “People always ask me, ‘Is that real?’”

Seara may receive the most attention of Yamada’s creations, but she is hardly his only work.

Yamada lives in his cramped two-bedroom East New York apartment among a prodigious collection of curious creatures of his own making. There, you’ll discover a bizarre menagerie of multi-headed mutants, enormous mythical beasts, pint-sized merchildren, and the remains of several space aliens, as well as stacks upon stacks of canvasses filled with surrealist self-portraits and scenes of mythic warfare.

Yamada and his artwork once lived in Coney Island, in the artist’s former Museum of World Wonders, until Hurricane Sandy hit in 2012. After the hurricane caused irreparable damage to Yamada’s gallery and home,he moved further inland along with his artwork, which, without a gallery, has become an assemblage of quiet but peculiar housemates.

Yamada is no stranger to sharing his home with creatures of a singular nature. He’s filled his bedrooms with taxidermic pets since he was a child living in Osaka, Japan. By the time he was six years old, he had compiled a massive collection of stag-horned beetles and two-headed lizards and snakes.

It was this penchant for art and taxidermy that led him to the United States in 1983, where he began studying at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland. From there, he worked on stage sets and large scale murals in amusement parks and theaters, along with his own peculiar artwork, until he moved to New York in 2000.

Yamada’s artwork is as fun as it is frightening, and the artist presides over his collection like a cheerful, Frankensteinian ringmaster. His showmanship is reflected in his regular outings with Seara, which he considers a fundamental expression of his work as an artist.

“The job of the artist is not creating artwork,” says Yamada, “It’s creating an artistic experience in people’s minds and hearts.”

Much of Yamada’s work is a macabre reappropriation of overlooked objects. His art frequently borrows from the commonplace detritus of everyday life. A pill bottle in his bedroom is filled with a year’s worth of fingernail clippings: “My nails,” he says, “a good art supply.” He’s used nail clippings in his artwork in the past—they’re evidenced in the spiky, textured skin of the tiny shriveled merchild carcass.

Other recycled elements in Yamada’s work are the carefully salvaged remains from meals at his favorite restaurants. A closer examination of one of Yamada’s enormous monsters reveals that its horns are electric green and black painted crab claws: leftovers from a dinner of long ago. In the windowsill of Yamada’s apartment a collection of bones congeals silently in a clear plastic cup—pork bones, Yamada explains, later to be used in a necklace he plans on wearing.

Yamada wears much of his artwork. He has created a collection of ornate, gold-painted crab and lobster claws that he often wears as an accessory to his lavish outdoor attire. Typically, the artist leaves his house dressed in a three-piece 1940s-styled suit, a lacey cravat, a colorful sash, and one of his many hats: top hats for the weekends, and during the week, a Fedora.

Yamada says that the way he dresses is a part of his personal philosophy, and he wishes that others would follow his example. “I’d like to see more men dressed in suits and more women wearing evening gowns,” he says.

“Why do people dress so badly when they go outside?” he asks, “You are the protagonist, the star of your own life, so why dress down? When you go out, you should display yourself to the best of your ability. Even if you go to McDonald’s, you should dress up.”

This penchant for pageantry is fundamental to Yamada’s self-image—ask Yamada if he considers himself to be an artist and he scoffs.

“I am not an artist,” he says, “I am art.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook