In Search of the Elusive Pink-Headed Duck

After years of trying, one man thinks he will finally find a bird long thought to be extinct.

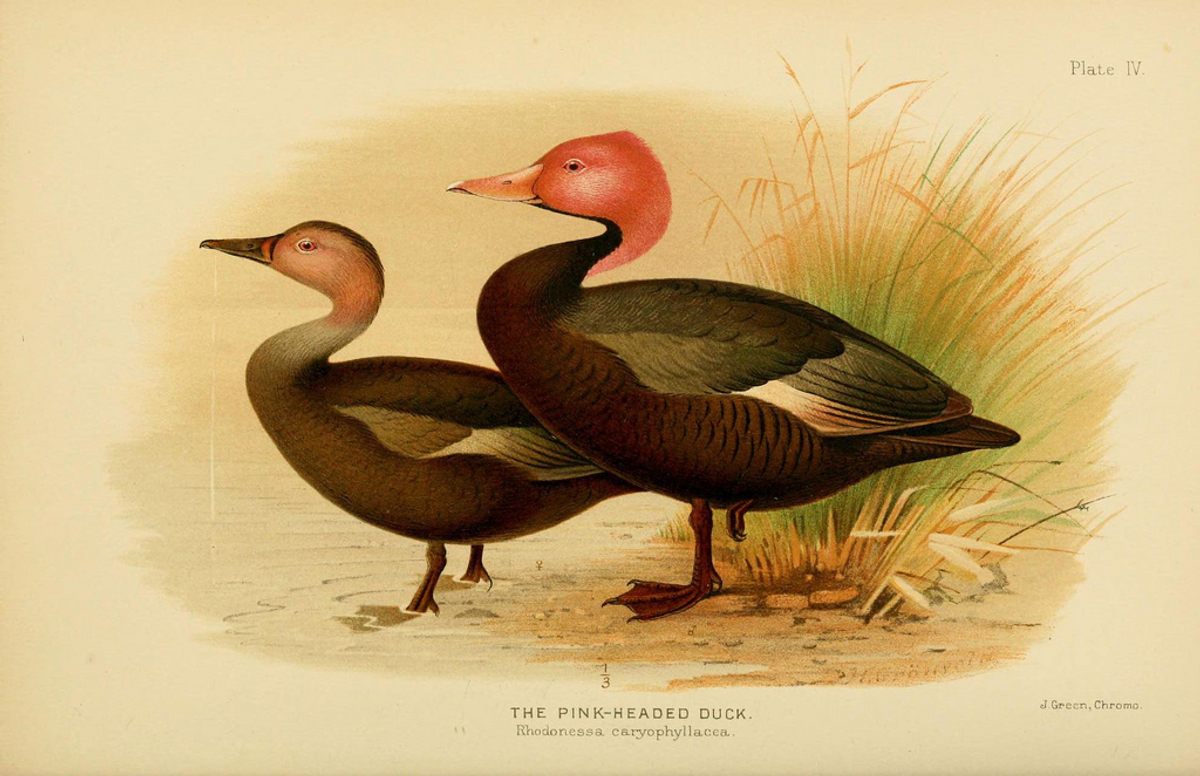

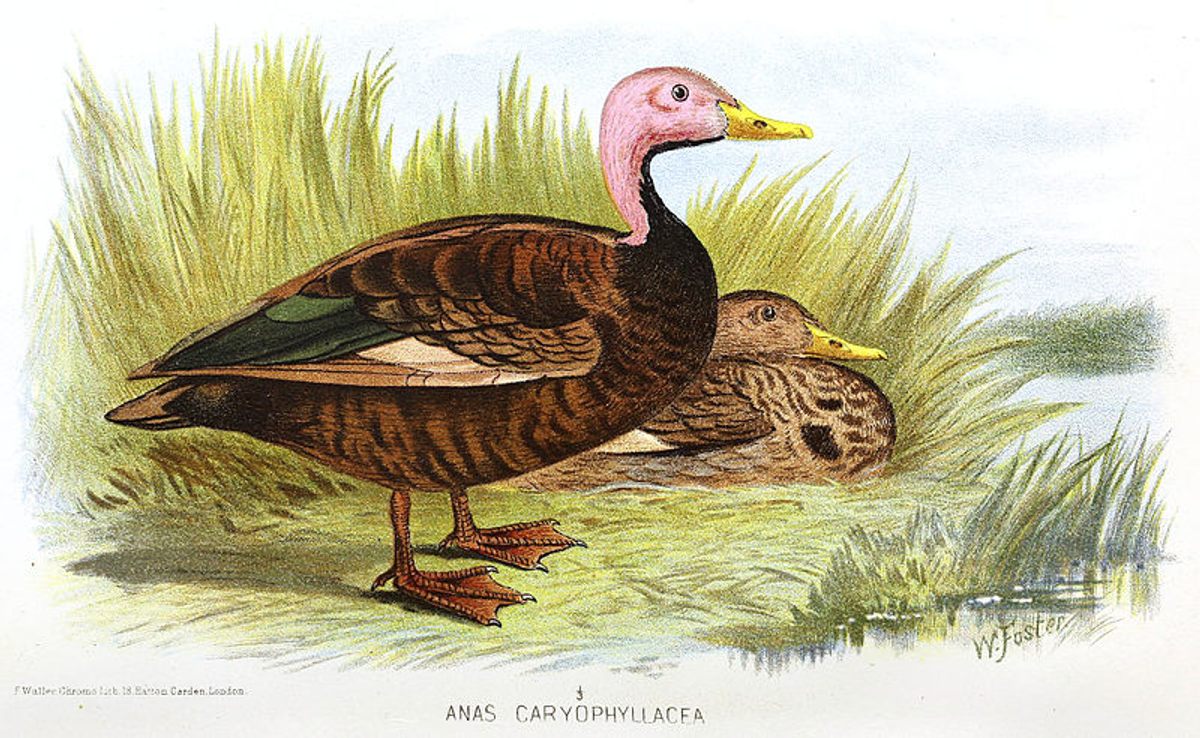

More than a century ago, in the wetlands around Kolkata, India, there lived a shy type of duck with a bright pink head. It was named, appropriately, the pink-headed duck. The males of the species had rosy pink bills and pink plumage covering their heads and necks. Some of them had light, blush-colored feathers; others were as bright as Pepto-Bismol. They were never particularly common, but hunters spotted them and on occasion bagged them while hunting bigger game. One of the last times anyone saw a pink-headed duck in the wild, it was in the mouth of a hunting dog, who delivered its carcass to Charles M. Inglis, curator of the Darjeeling museum, outside the Indian city of Darbhanga in June 1935.

Officially, the pink-headed duck is listed as critically endangered. The last confirmed sighting in the wild was in 1949. Though there have been reports of pink-headed ducks here and there in the decades since, many people now believe the birds are not just rare and shy, but extinct.

Richard Thorns is not among them. For years now, he has been searching for the pink-headed duck, and, since 2009, he has traveled six times to Myanmar, where he believes a flock of about 50 birds might live. Thorns, an enthusiastic, 53-year-old Englishman whose look can range from scholarly nerd to rugged adventurer, first learned about the pink-headed duck around 1997, from a library book on vanishing birds. At the time, he was working as a shop assistant. As he read about these stunning, rare birds, and the elephant grasses and lotus flowers that they lived among, he had a realization. “I didn’t want to be a shop assistant anymore,” he says. “I decided to look for the pink-headed duck. So I did, and I’ve been after it ever since.”

From his journeys in Myanmar, Thorns has developed a theory about exactly where the pink-headed duck could be hiding, and this fall he plans to return for a seventh search, as part of the Search for Lost Species. The campaign, created by Austin-based nonprofit Global Wildlife Conservation, will attempt to relocate a handful of more than 1,200 species considered “lost to science”—long unseen, unrecorded, and feared extinct. A century ago, pink-headed ducks could be found in Myanmar, and Thorns believes that it’s very possible the ducks are living there still, in parts of the country long closed to outsiders, out of sight of birdwatchers and conservation organizations.

To some, there’s little point in a quixotic search for a lost duck. These birds supposed to be extinct, after all. “The people who hope for the pink-headed duck are people prepared to think in a different way,” Thorns says. “It’s like a detective story. Have we just missed it? Or is it hidden where no one can go?”

Thorns is not the first to go looking for the elusive waterfowl. In the 1980s, Rory Nugent, an American adventurer and writer, heard about the duck from a friend. By two months later, he had sold his apartment, had put his belongings in storage, and was on his way to India. Like Thorns, Nugent believed he could find the duck in a part of the world troubled by violent conflict and usually off-limits. He waited for months for permission to travel the Brahmaputra River in Assam, which he spent searching for the duck in the bird markets of Kolkata (then still called Calcutta), in the towns of Sikkim, and on the border of India and Tibet. Finally, he and Shankar Barua, an artist and photographer whom he met in New Delhi, set out down the Brahmaputra and scoured the river for weeks. He never got a clear glimpse of his quarry, but by the end of the journey Nugent insisted, “We’ve seen it. We just didn’t notice it. … They’re not extinct, just hard to find.” His book about the adventure ends with a reported sighting and the author heading back upriver.

Part of the mystery surrounding the pink-headed duck is why it disappeared to begin with. Most species are driven to extinction by habitat loss, hunting, or predation by an invasive species, but there’s no obvious cause for the pink-headed duck’s disappearance. Though its habitat has diminished and it was hunted, other birds have survived the same circumstances. Since the pink-headed duck was always relatively rare, it is possible to imagine the bird is still hiding somewhere out there. Nugent’s report, another from Myanmar in 1968, and other more recent sightings are not considered robust enough to count as evidence for the duck’s continued survival. But stories of pink-headed duck sightings keep popping up, and some of the most recent come from the exact area of Myanmar where Thorns has been searching.

In 1910, a pink-headed duck, now stuffed and held at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, turned up at a bazaar in Mandalay, one of the country’s largest cities. Since then, unconfirmed reports of the ducks have come from the country’s northern districts. In the early 2000s, two conservation groups—BirdLife International and Myanmar’s Biodiversity and Nature Conservation Association (BANCA)—began surveying rivers, lakes, and wetlands in the region for pink-headed ducks.

In December 2004, the team was in the Nawng Kwin wetlands, north of vast Indawgyi Lake, when they met a young man named Saw Aung, who said he was familiar with the duck. One morning, the group went out into the grasslands, and Saw Aung flushed a flock of ducks from a wetland pool. A few dozen mallards rose into the air, and as three foreign birdwatchers peered through telescopes, one duck “broke off from the flock, climbed quite high, circled for 2 to 3 minutes, and then descended into the grassland,” the team later wrote in a published report. The three men agreed: The bird, medium-sized, had a pale head and neck, a dark body, and dark upper wings. It looked a lot like a pink-headed duck.

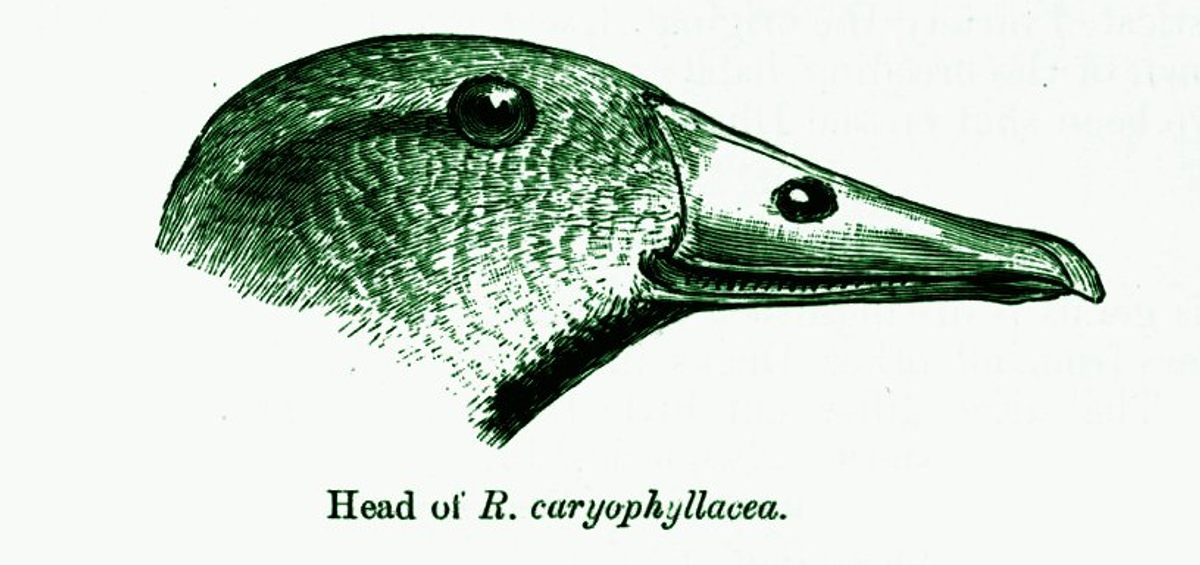

In that part of the world, though, there is another bird with similar features, the spot-billed duck. The men discussed the features that would distinguish one bird from another—in particular, white feathers on the underside of the wing, a characteristic of the spot-billed duck. Had they seen those feathers? One of the three observers thought he had. Though another thought it was “very likely” they had seen a pink-headed duck, the other two weren’t so sure. They couldn’t rule out the possibility that they’d seen a variety of spot-billed duck. “On balance, therefore, this record should be treated as a possible but unconfirmed sighting of Pink-headed Duck,” they wrote. The thrilling moment had passed too quickly for any semblance of certainty.

Before beginning his search, Thorns was not a serious birder. “My brother is the person to talk to there,” he says. “He is a real hotshot birder.” But once he heard of the pink-headed duck, he never forgot about the bird, its beauty, and the beauty of its habitat. “I inherited my grandfather’s instincts as an explorer,” he says. “I think a lot of it was … I wasn’t doing very much. I didn’t really feel fulfilled. The pink-headed duck is like some sort of mythical thing. It is so iconic and beautiful.” The idea of finding something missing for so many years gave him a mission.

In his first visits to Myanmar, Thorns tried to keep himself and his purpose as well concealed as the fowl he was searching for. Before 2011, the country was still ruled by the military junta that had been in power since 1962, and even today the government restricts the movements of foreign travelers in certain parts of the country. Myanmar is rich in jade, gold, and other treasures. Some of the most resource-rich areas are off-limits, and in the north ethnic independence armies are still in conflict with government forces. But for pink-headed duck seekers, those same areas are some of the most promising targets, full of marshy, undeveloped, restricted habitat. To find the duck, Thorns figured he would need to sneak into places he technically was not supposed to be.

Thorns made his way north to visit towns on the Ayeyarwady River, following historic reports, and to Indawgyi Lake, where the 2004 expedition made its possible sighting. In Bhamo, he sought out a man named Sein Win. Thorns had read in a Lonely Planet guide that this man was locally famous for having built his own helicopter. “I figured that if he was eccentric enough to have built a helicopter, he might not be too averse to being my guide,” Thorns says. They snuck farther upriver than the government allowed, but they did not go unnoticed. One time they had to wait on the boat until night fell to sneak downriver, hide in a temple, and pretend they were coming back into town from the south. Another time, Thorns traveled to a promising lake only to find it was on the wrong, off-limits side of the river. He had to offer a boatman “a million kyat”—hundreds of dollars—to take him across.

All that risk-taking had an impact. On his third trip, in 2012, the conflict in the country’s north had heated up, and sneaking upriver on a boat was no longer an option. So Thorns rented a bicycle and tried to pedal out of town. “Looking back at it now, it was a mad thing to do,” he says. On the small road, two kids roared by on a motorbike, and as Thorns fell, his hand collided with their vehicle. A well-meaning woman brought him ointment, but he knew the hand was broken. Even today he can’t open it properly.

That year Thorns spent part of his trip relaxing on the beach and in Mandalay’s public baths, but it was a breakthrough of sorts. He had first learned about the pink-headed duck in his early 30s, and he was then in his late 40s. He had worked for more than a decade as a driver, mostly for a local hospital, and never had much money. Financing the trips required single-minded purpose—between each he worked as much as possible to pay off debts from the previous one and save for the next. It’s been a very long time, he says, since he’s had girlfriend. Though he had some financial help from an anonymous backer, over the years, he estimates he has spent £12,000—the equivalent of $15,000 at today’s exchange rate—of his own money on his fruitless search. It wasn’t wise, but it was worth it, he believed. If he could find the pink-headed duck, he could change history. But he needed to change his strategy. He resolved to stop sneaking around and embrace the authorities.

Through BANCA, Thorns built relationships with guides and travel agencies to help him get permits to travel to the more remote places on his list of potential pink-headed duck hotspots. On his most recent trip, in 2016, he had an experience that convinced him he might be getting closer. On his last day in the field, he was in a village where he’d been in 2010. Thorns and his guide were showing their bird book to locals, and one man came into the café. He pointed to the pink-headed duck and said that the bird was very rare.

“Has he ever seen it?” Thorns asked, through the guide and interpreter, Lay Win.

No, he hadn’t, the man replied. Thorns probed further. Had he never seen it at all?

Oh, he had seen it elsewhere, the man said. It was five or six years ago … up in the wetlands.

“I was there in 2010; I was just asking the wrong person in the village,” says Thorns. “He said that it was very rare and extremely shy. You can only find it in a certain part of the wetlands.”

That night, Thorns and his guide were sitting by the water, having a beer. Thorns asked the guide, whom he describes as “very cautious guy,” if he thought the man had really seen the duck.

“Yes,” he said. “I think he did see it.”

After consulting with BANCA, Thorns now believes that the pink-headed duck may visit that area in the wet season before migrating elsewhere, to a valley where outsiders are not allowed, for the rest of the year. “The people who were reporting the pink-headed duck were not tourists or birders,” he says. “They were hunters, travelers, farmers. They’re all people who have no choice but to go into a swamp in the rainy season.” He now plans to return to Myanmar this fall, starting in the last week of October, when traveling the country is “like being in a washing machine,” to continue the search. He is working with Global Wildlife Conservation to fund the trip, but his team is also raising funds on its own. This time, Thorns also plans to hire an elephant to help flush the birds out and increase the chance that the pink-headed duck will briefly reveal itself.

If Thorns and his companions on this next journey, naturalist and writer Errol Fuller, photographer John Hodges, and Hodges’s partner, Pilar Bueno, do make a sighting, they may need to keep the exact location secret. “I can’t emphasize enough how sought after a pink-headed duck head would be,” Thorns says. “You have to be very, very careful.”

In fact, it’s possible that a European birdwatcher has already seen the duck in the same area Thorns will search. When Thorns visited the area the first time, he was told about a Dutch man who came each year, for five years, and hired an elephant, in search of the pink-headed duck. On his fifth visit, he came back from the wetland triumphant—he was sure he had seen the bird, he told locals, but had not managed to take a picture.

“You don’t know how you will behave” upon finding the duck, says Thorns. “I remember once finding an opal in this old abandoned heap of junk. There was a dividing line—I went from not having an opal to having an opal in my pocket. But these things happen. It’s hard to know how you’re going to react.” If all goes well, it will be the same scenario. One minute, no one will have definitively seen the duck for decades. The next, Thorns will have conclusively identified, photographed, and rediscovered the pink-headed duck. Known again to science. No longer lost.

“If anyone is going to find the pink-headed duck,” he says, “I want it to be me.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook