The Scientific Squabble Over the Dodo Tree

An extinct bird, an ailing tree, and a controversial hypothesis.

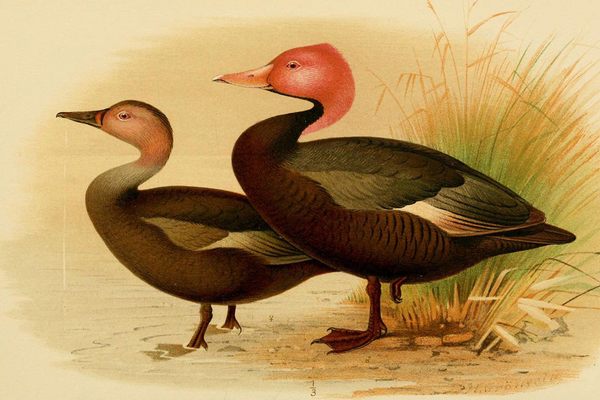

The dodo is Mauritius’s mascot. (Photo: Public Domain).

Correlation is not causation. For some reason, as many times as this phrase gets repeated, it doesn’t seem to get less true. And sometimes, this human fallacy gets written into scientific record. Take the intriguing tale of the dodo tree.

On the small volcanic island of Mauritius just east of Madagascar live large hardwood trees with vines draping from their wide canopies. The trees go by several names including the tambalacoque tree, Sideroxylon grandiflorum, and, formerly Calvaria major—most famously, the “dodo tree.”

In the late 1970s, botanist Stanley Temple hypothesized that the tree and the dodo bird—native to Mauritius and extinct since the 1680s—had been involved in a mutualistic relationship. The trees were prevalent in the forests 300 years ago, when dodos reigned over the island. In 1973, however, Temple found that there were very few juvenile trees on Mauritius. Ever since the death of the dodo, Temple believed, the tambalacoque trees were declining.

The Mauritius coat of arms features the dodo. (Photo: Escondites/CC BY-SA 3.0)

The theory sounded good. In the paper he published in the journal Science in 1977, Temple wrote that, “the dodo possessed a well-developed gizzard that contained large stone, which were used to crush tough food.” These stones were perfect for crushing seeds from fruit-bearing trees. Like peach pits, the seeds in the fruit of tambalacoque trees have a tough, thick endocarp (the outer covering of a seed) that must be broken down somehow to germinate and grow.

Temple connected these facts, suggesting that the tambalacoque tree evolved the thick shell so it could protect the seed inside while it passed through a dodo’s gizzard. Then after digestion, it would be easier for the seed to germinate. So no dodo, no tree.

To test his mutualism hypothesis, he conducted an experiment with turkeys, which also use gastroliths—small stones and sediment in their gizzards. He force-fed fresh tambalacoque seeds to 17 turkeys, and 10 successfully passed through the gizzard and were digested or regurgitated. He planted the 10 seeds and three germinated. In the conclusion of his paper, Temple wrote: “These may well have been the first Calvaria seeds to germinate in more than 300 years.”

Temple concluded that the dodo’s extinction led to the tambalacoque trees’ dismal numbers. But his mutualism study didn’t quite check all the boxes.

“It’s a lovely story,” naturalist Gerald Durrell wrote in his book Golden Bats and Pink Pigeons. “But I’m afraid it’s got more holes in it than a colander.”

It didn’t take long for Temple’s paper to become an academic punching bag, as both his methods and his conclusions were flawed. It was discovered, for instance, that Temple didn’t plant non-ingested seeds to compare germination rates. He also failed to acknowledge a previous study that indicated that the seeds didn’t need to be worn down by a bird’s digestive tract to germinate.

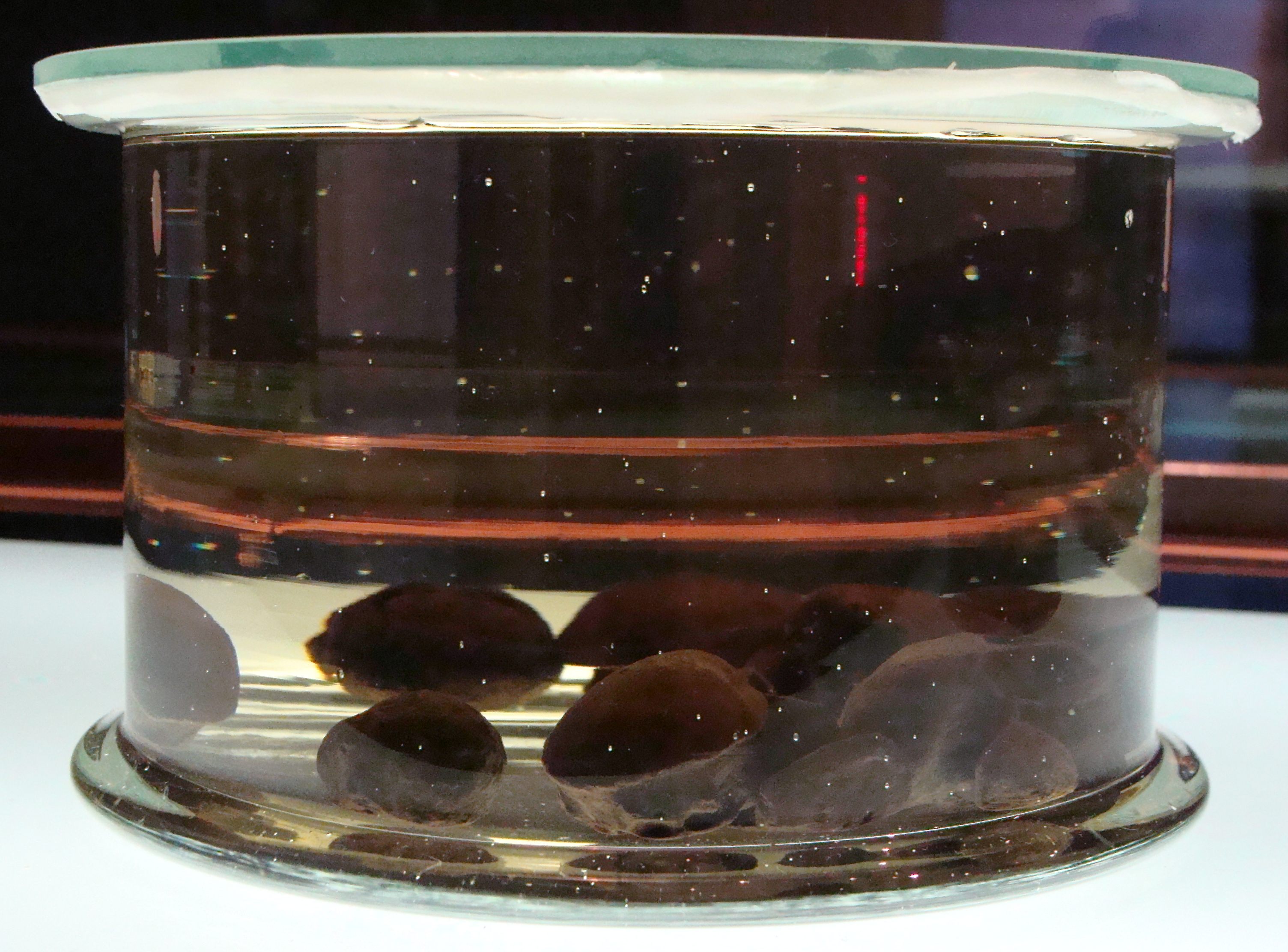

Tambalacoque tree seeds have a thick outershell, similar to peach pits. (Photo: Peter Maas/CC BY-SA 3.0)

More people jumped in the fray. In 1979 Science published an editorial by A.W. Owadally, an official of the governmental forestry service of Mauritius, in which he criticized the facts in Temple’s paper and wrote it was unlikely that the dodo and the tree were even in the same area of the island. He also brought forth data from a 1941 survey of the forests that showed a good population of young tambalacoque plants that were certainly less than 75 to 100 years old. This meant that trees were able to germinate after the dodo became extinct.

Temple entered the debate and defended the reasoning behind his hypothesis by publishing a defense to Owadally’s editorial. In the same issue of Science, Temple admitted that the tambalacoque tree-dodo mutualism was impossible to prove experimentally after the dodo’s extinction: “What I pointed out was the possibility that such a relation may have occurred thus providing an explanation for the extraordinarily poor germination rate in Calvaria. I acknowledge the potential of error in historical reconstructions.”

Other scientists have since proposed alternative reasons for the disappearance of the tambalacoque trees, suggesting that other animals that have since become extinct on the island, like the Mauritian giant tortoises, could have also helped distribute and germinate the seed.

It’s not impossible that the dodo was partially responsible for assisting tambalacoque tree seed germination 300 years ago. But Temple’s experiment lacked the evidence to prove the bird’s extinction was the cause of the dodo tree’s decline.

There is a silver lining to this story, though. Thanks to the controversy over Temple’s research, the tree’s plight got attention. Botanists now use different techniques to break down the seeds’ outershell to aid germination, such as gem tumblers and polishers. The dodo bird may be long dead, but there are reports that the dodo tree population is rising.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook