Fannie Quigley, the Alaska Gold Rush’s All-in-One Miner, Hunter, Brewer, and Cook

She used mine shafts as a beer fridge and shot bears to get lard for pie crusts.

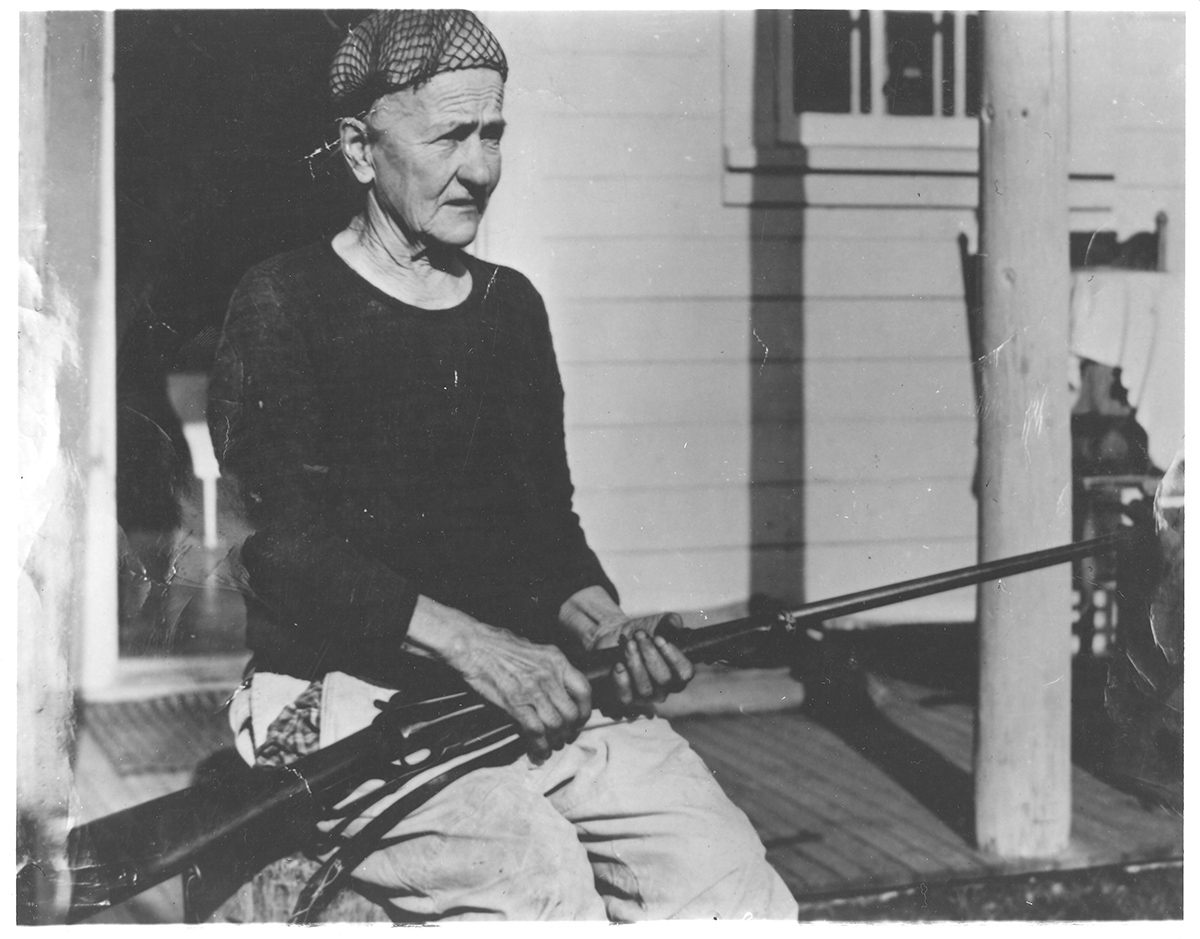

Tales of Alaska’s gold rushes, which began in the 1890s, are full of larger-than-life men—bold, cantankerous fellows who drank and swore and shot as they chased promises of gold across the stark, untrammeled tundra. But nestled among all the stories of men is the story of Fannie Quigley, a five-foot-tall frontierswoman who spent almost 40 years homesteading and prospecting in Kantishna, a remote Alaskan mining region that would later become part of Denali National Park.

Like the men around her, Quigley drank, swore, and shot bears—but unlike those men, she used her bear lard to create the legendarily flaky crusts of the rhubarb pies she served to her backcountry guests.

Over her decades in the backcountry, Quigley acquired a reputation as not only a renowned hostess and cook, but one of the finest hunters the region had ever seen. Her guests—who were many, despite the fact that her cabin was only accessible by foot or dogsled—were universally impressed by the woman who “tracks her own game, prefers to hunt alone, skins and dresses, packs and caches even such massive beasts as moose and bear, skins out the cape and horns of mountain sheep and can both butcher and cook any game meat to the queen’s taste.”

As Jane G. Haigh details in her book Searching for Fannie Quigley: A Wilderness Life in the Shadow of Mount McKinley, Quigley was born in Wahoo, Nebraska, in 1870 to a community of Czech-speaking immigrants from the Bohemian region of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Her upbringing inured her to unforgiving environments and ruthless austerity, and her family subsisted as farmers during a time of record-breaking blizzards, plagues of locusts, systemic financial collapse, and a drought that lasted seven years. Still, something in the harsh landscapes and scarce resources of her childhood captured her fascination, and Fannie spent the rest of her life deliberately seeking out the demanding freedoms of the frontier.

At the age of 16, Fannie left home and headed west following the rapidly expanding Union Pacific railroad, where she took jobs cooking in work camps. It was in these camps that she honed her rudimentary English—and, likely, acquired the rich vocabulary of cuss words (once described by a visitor as “figurative language that was fairly Shakespearian [sic] in its rugged raciness”) that would grow to be a cornerstone of her reputation.

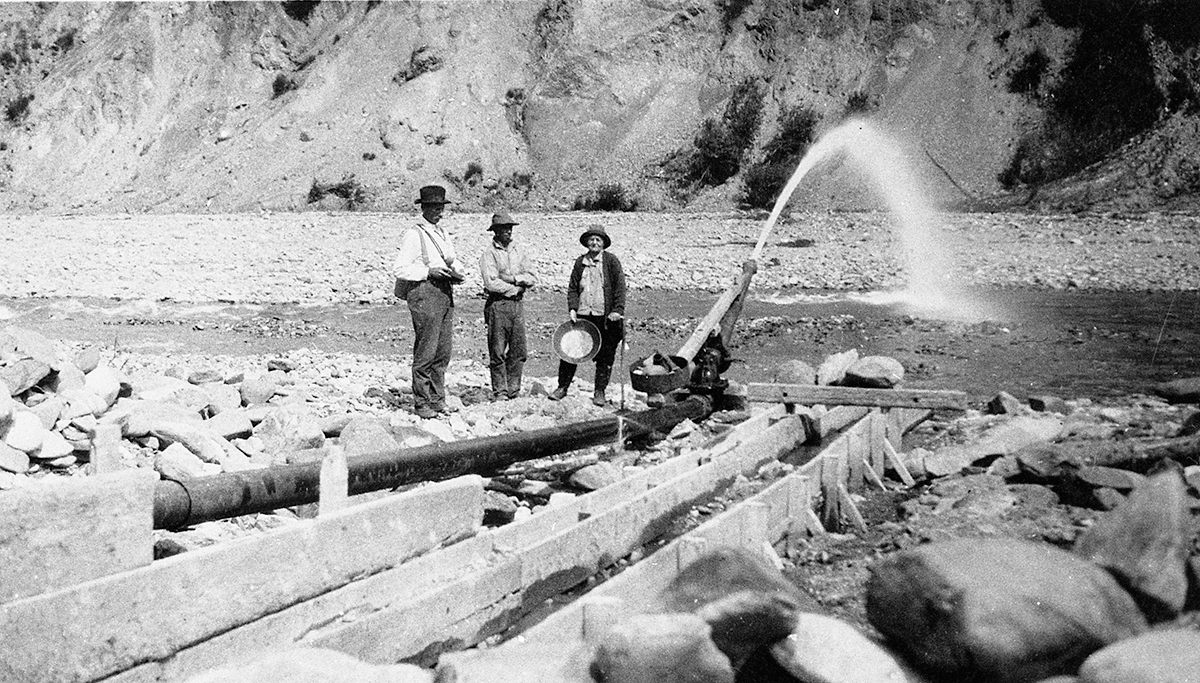

After arriving on the West Coast, Quigley heard whispers of gold in the North and latched onto reports that it was impossible to find decent food. Counting on her experience as a camp cook, she joined the rush surging north to the Klondike and landed in Dawson City, Canada, in 1897. She quickly learned that miners, in their haste to be the first on site to stake new claims, would stampede into the backcountry without even the most basic essentials needed to feed themselves. Capitalizing on this lack of foresight, Fannie earned herself the nickname “Fannie the Hike” by walking dozens—sometimes hundreds—of miles into the wilderness with her sheet-metal Yukon stove and kitchen gear to set up shop fixing meals for ill-prepared miners.

Though Fannie entered the gold rush through cooking, she quickly got into the mining game herself, and in 1900, staked her first claim in Clear Creek, which lay over 100 miles east of Dawson. Here, she met her first husband, Agnes McKenzie. The pair married on October 1, 1900, and together they operated a roadhouse near the small settlement of Gold Bottom. The two were well-known drinkers, and their relationship was punctuated with screaming matches, broken furniture, and mutual black eyes. In 1903, Fannie walked out of both her front door and her marriage—and kept walking for 800 miles down the Yukon River before crossing out of Canada and landing in the town of Rampart, Alaska.

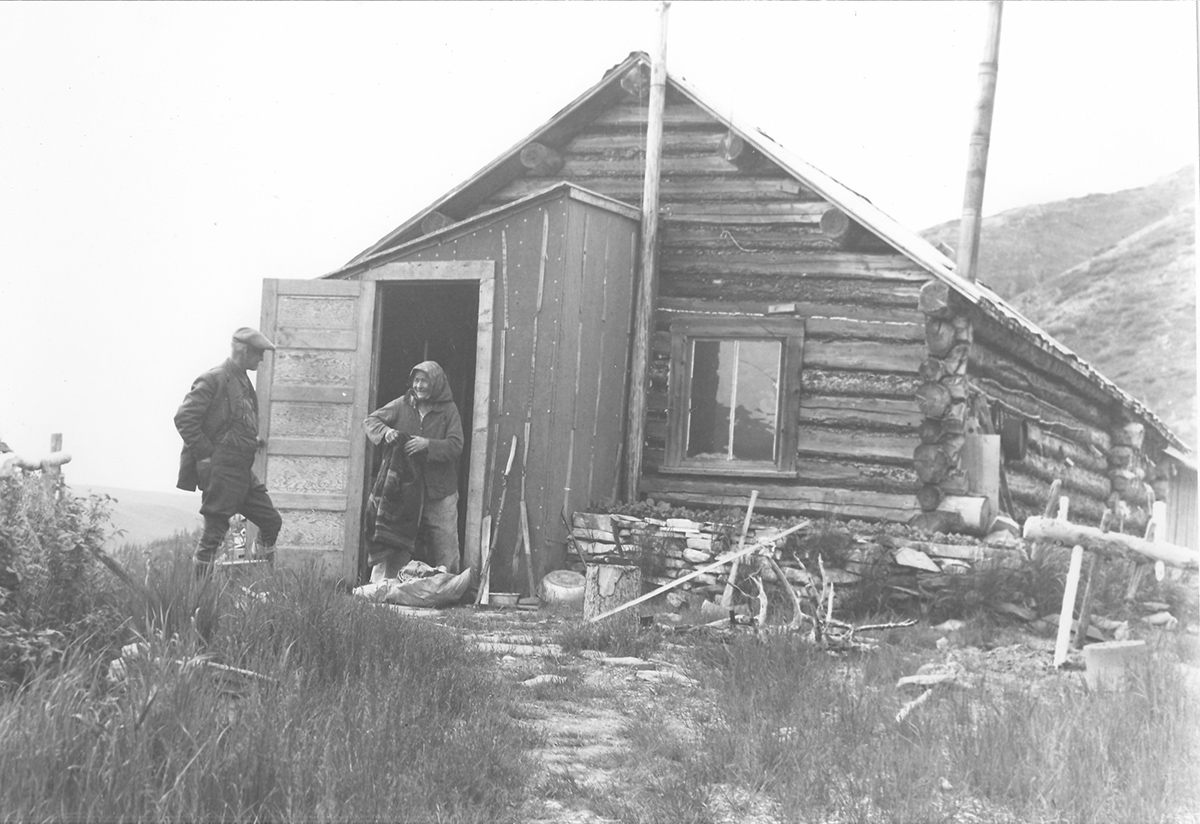

After a handful of years chasing rumors of rich claims in the frontier towns of Tanana and Chena, Quigley set out in 1906 towards whispers of gold in Kantishna, a remote patch of tundra that lay hundreds of miles and multiple mountain passes from the nearest town. No roads led into the region, and supplies were arduously pulled in by dogsled. It was here, amidst rolling hills that looked out on the jutting peaks of Mt. McKinley and the Alaskan Range, that Fannie crossed paths with her second husband, “long legged” Joe Quigley. Although the pair lived together for over a decade before becoming officially married in 1918, friends and community referred to them as man and wife out of a discomfort with the societal shame of unmarried cohabitation.

Despite its initial promise, Kantishna never truly panned out as a mining region, and within a decade, its population had shrunk to fewer than 50 residents. Although she staked 26 claims between 1907 and 1919, Quigley’s dreams of striking it rich never materialized. Instead, she honed the skills that would eventually cement her reputation as an unparalleled backcountry cook. She learned to hunt bear, moose, and caribou, and to set trap lines for lynx, wolverine, and fox. She built a series of raised garden beds that allowed her to grow a rich array of vegetables out of the reach of the frigid tundra permafrost, and she planted grass to spread as bedding for visiting dogsled teams. She perfected her recipe for potato beer, and used the temperature differentials in Joe’s mine shafts as her own calibrated refrigeration system.

News of the Quigleys spread to the outside world only by virtue of the fact that their cabin lay along the route for mountaineering expeditions setting out to conquer Mount McKinley (which is what Denali was officially called between 1917 and 2015, when President Obama restored the original Koyukon name). The Quigleys’ fortuitous location ensured that the couple saw a steady stream of visitors over the years, including such notables as the writer Jack London. In later years, people became so curious about “the little witch of Denali,” that visitors would make the trek to Kantishna solely to meet the infamous Fannie Quigley.

In a 1913 article in Outing Magazine, painter and mountaineer Belmore Browne wrote of meeting Quigley while returning from an attempt to summit Denali:

“Our hostess was one of the most remarkable women I have ever met … She lived the wild life as the men did, and was as much at home in the open with a rifle as a city woman is on a city avenue … From a physical standpoint she was a living example of what nature had intended a woman to be and, furthermore, while having the ability to do a man’s work, she also enjoyed life as a man does … In this wilderness she had built a home that would do credit to civilized communities … A fresh-killed moose skin was nailed to the floor, hair side down, and a magnificent sheep head hung on the wall. There was a liberal supply of reading material, and a large range in the corner gave promise of pleasant things in prospect for the inner man. From the window you could see a flower garden, while below a truck garden flourished inside a pole fence.”

In the same article, Browne described one of Quigley’s feasts:

“First came spiced, corned moose meat, followed by moose muffle jelly. Several varieties of jelly made from native berries covered the large slices of yeast bread, but what interested me more was rhubarb sauce made from the wild rhubarb of that region … These delicacies were washed down with great bowls of potato beer, ice-cold from the underground cellar.”

Quigley succeeded in building an impressive home for herself, but she felt the weight of its isolation: for the majority of her time in the Kantishna region, she was the sole member of her gender. And while she was often disdainful of other women, Quigley missed them. In a letter to her friend Charles Sheldon, who was seminal in the founding of Denali National Park, she wrote, “I went to Fairbanks last fall. that [sic] was my first trip to town in seven years. I didn’t see woman for three years. I tell you, I got lonsome. [sic] I have not seen automobile yet.”

All told, Fannie Quigley spent over 30 years living in Kantishna. She and Joe divorced in 1937 after Joe fell in love with a nurse while convalescing from a mining injury in a hospital in Fairbanks; Joe moved south to Seattle, and Quigley remained. In 1944, at 74 years of age, Quigley died alone at in her cabin: by all accounts, it seems that she built a cooking fire and lay down to rest before lighting it, and simply passed away in her sleep.

Quigley’s final cabin, complete with cupboards and counters built to suit her diminutive stature, still stands out at the end of the 90-mile dirt road that runs into Denali National Park. Now operated by the National Park Service, visitors can enter her cabin and see the home where, in the words of her Fairbanks Daily News Miner obituary, “One of Alaska’s most colorful pioneers came to the end of her tread.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook