The Forgotten History of the Controversial Sister Serpents

A feminist art collective stirred up trouble in the 1990s before fading from view.

This story reproduces Sister Serpents art that some may find offensive. Proceed with caution.

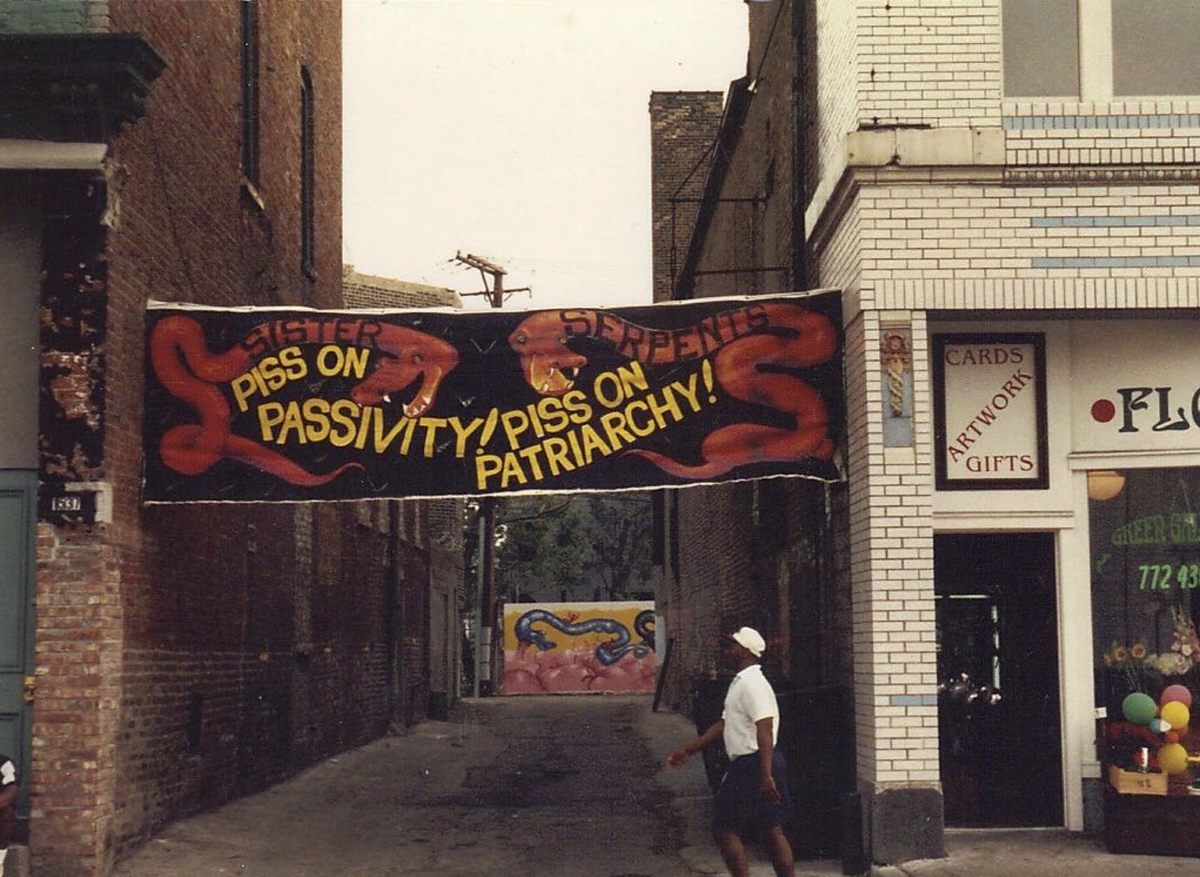

The Sister Serpents used to wear security guard uniforms when they went out postering. Once or twice a week, they hit the nighttime streets of Chicago with a stack of posters and plastered them all over. This sort of guerrilla street art isn’t exactly legal, so the uniforms provided a measure of safety.

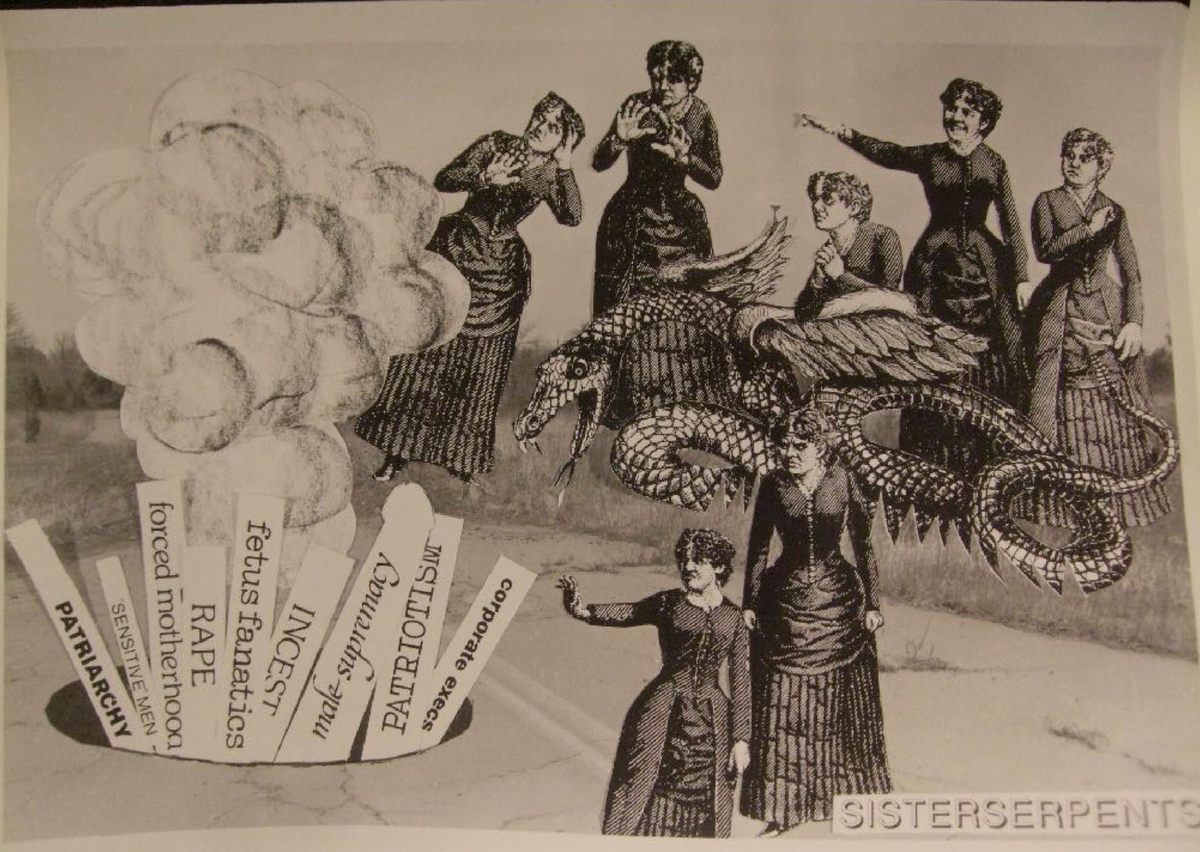

The feminist art collective started in 1989 with an ad placed in the paper, and every week a small group of radical women got together to make new, provocative posters. At first, they were simple enough—created on copy machines, the posters paired simple images with quotes. “The modern individual family is found on the open or concealed slavery of the wife,” one read, quoting Frederick Engels, coauthor of the Communist Manifesto.

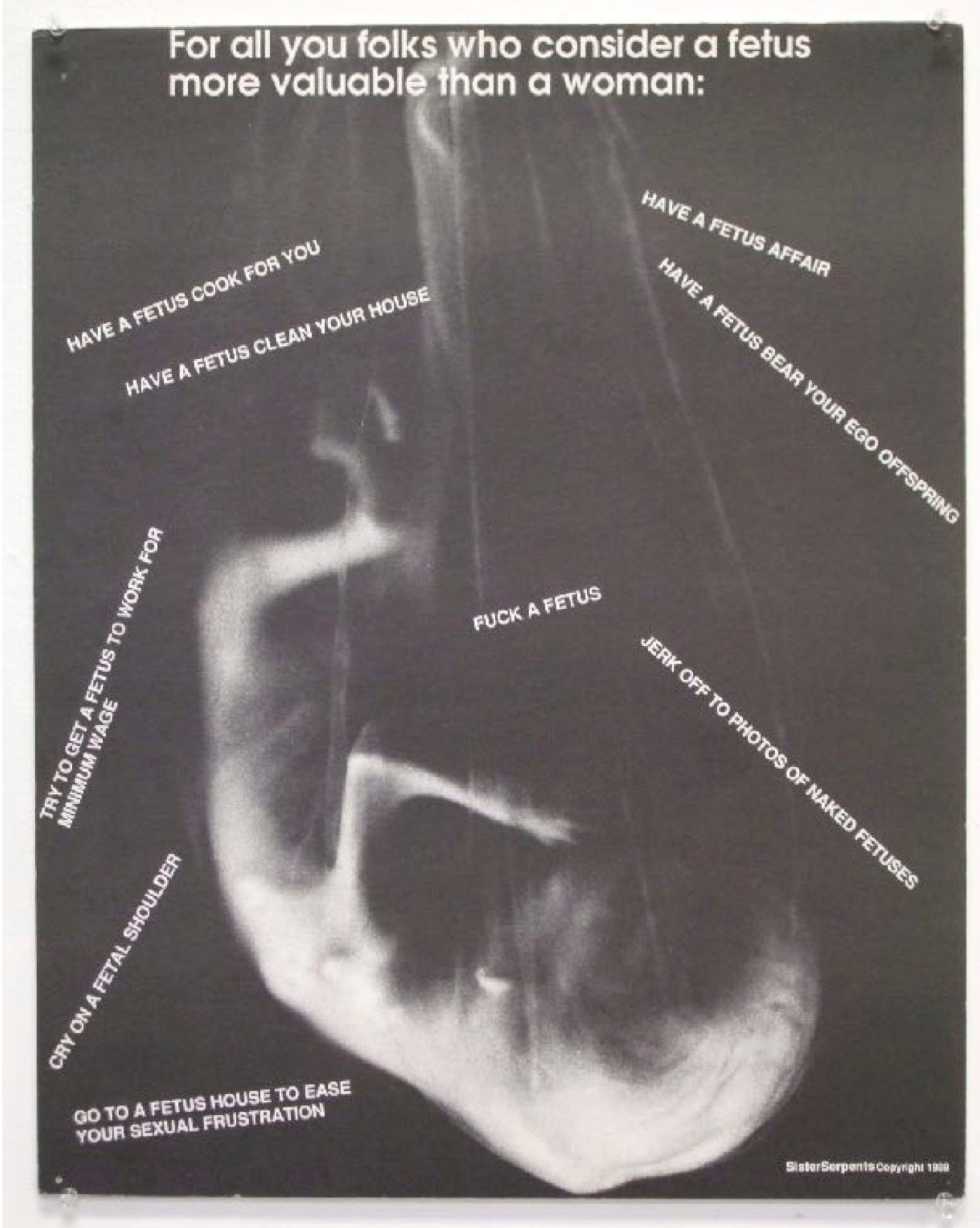

But it was the fetus posters that launched the group to notoriety. In 1989, the Supreme Court had held up a Missouri state law that restricted the use of state resources for abortions, and the group’s members were angry about it. They wanted to do something that would make people sit up and take notice. One of them had captured haunting black-and-white photographs of a fetus preserved in a specimen jar, and they started there.

They hung up the photographs and threw out suggestions of what they might tell someone who considered a fetus “more valuable than a woman.” Have a fetus clean your house… Try to get a fetus to work for minimum wage… Cry on a fetal shoulder. The idea that made it to the center of the poster, though, was more direct and potentially offensive.

“’Fuck a fetus,’” said Jeramy Turner, a painter and one of the group’s founders, at a recent talk at the Interference Archive in Brooklyn. “That was what caused all the trouble.”

Suddenly, the mainstream American media began to pay attention to an anonymous group of artists. The right-leaning Heritage Foundation and right-wing radio hosts denounced them. Reporters wanted to interview them. At the same time, this group of a few women grew rapidly into an movement; their sense of outrage had found an eager audience of women.

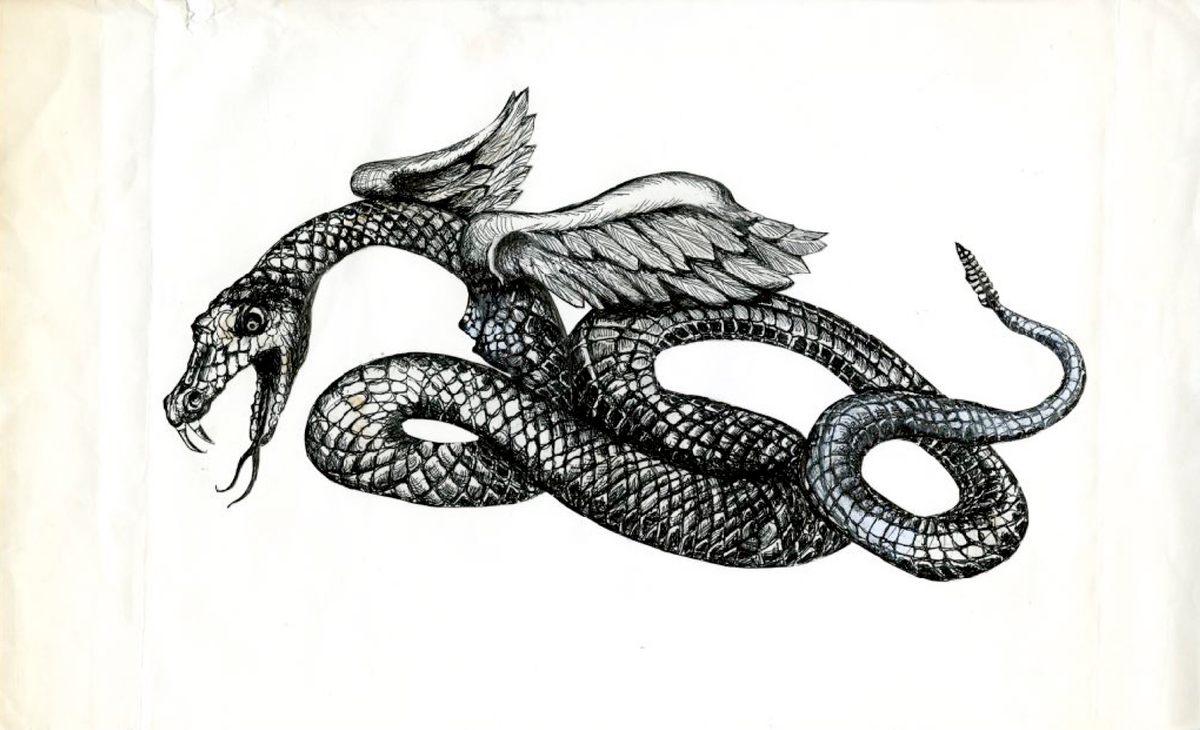

“We were effective, vibrant, and, we thought, revolutionary,” Turner said. While mainstream 1990s feminism was about advocating for equal pay and equal rights, the Sister Serpents sought “the demise of oppression and patriarchal power.” For about a decade, the Sister Serpents created posters, put on exhibitions, and made many people very, very angry.

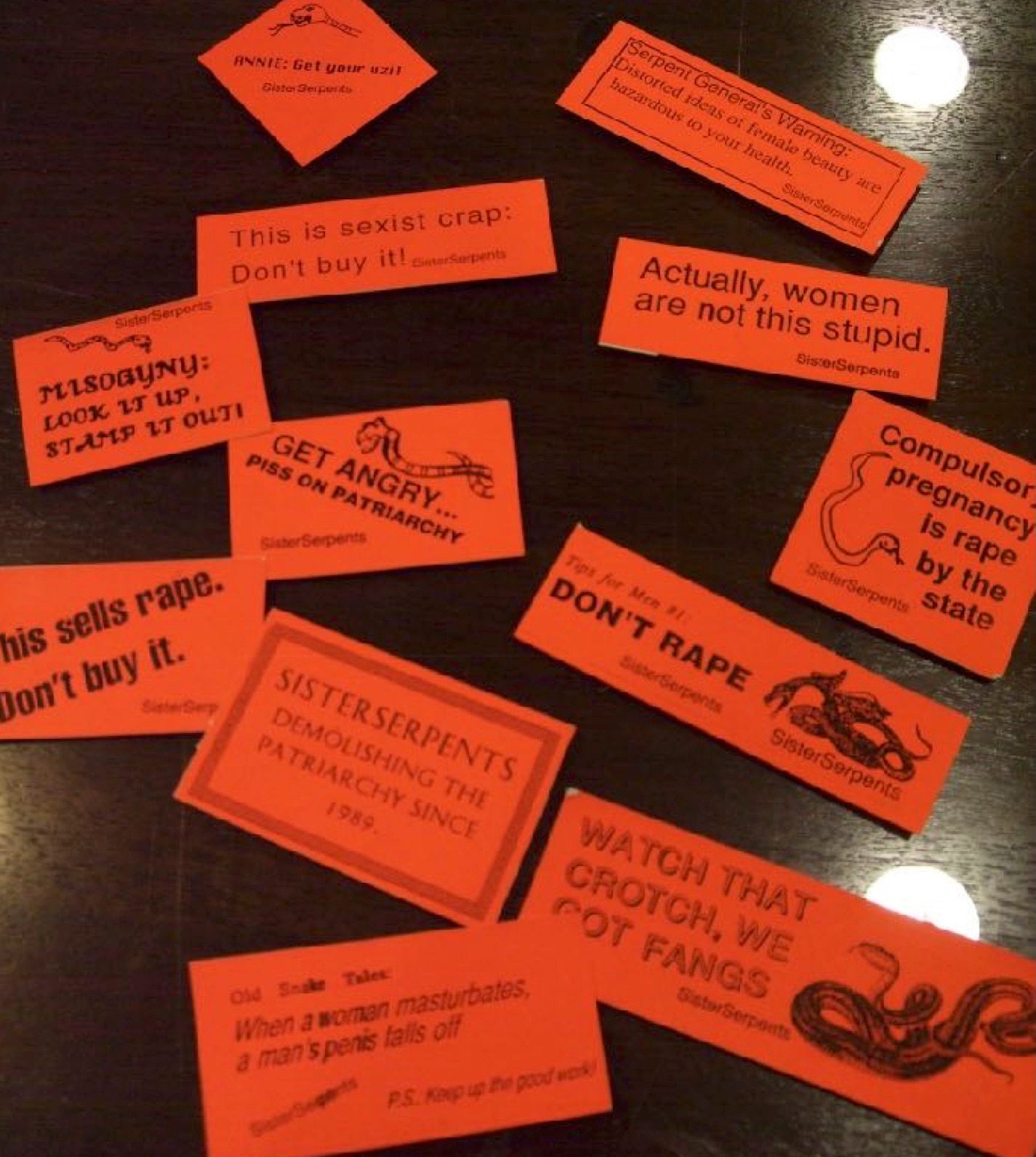

The Serpents had some sense that the fetus poster would unnerve people. Originally they had trouble finding anyone willing print it. When they finally found a printer to make 5,000 copies, they mailed copies of the poster to feminist writers and magazines, and put them up on the streets as they had their earlier works. Their other work was cheekier, not quite so dark. Around the same time, they were distributing bright orange stickers that could be plastered on women’s magazines or in public places, with slogans such as, “Tips for Men #1: Don’t Rape.” Soon they heard reports that their stickers were spotted as far away as India and, boosted by their newfound notoriety, they began planning their first major exhibition.

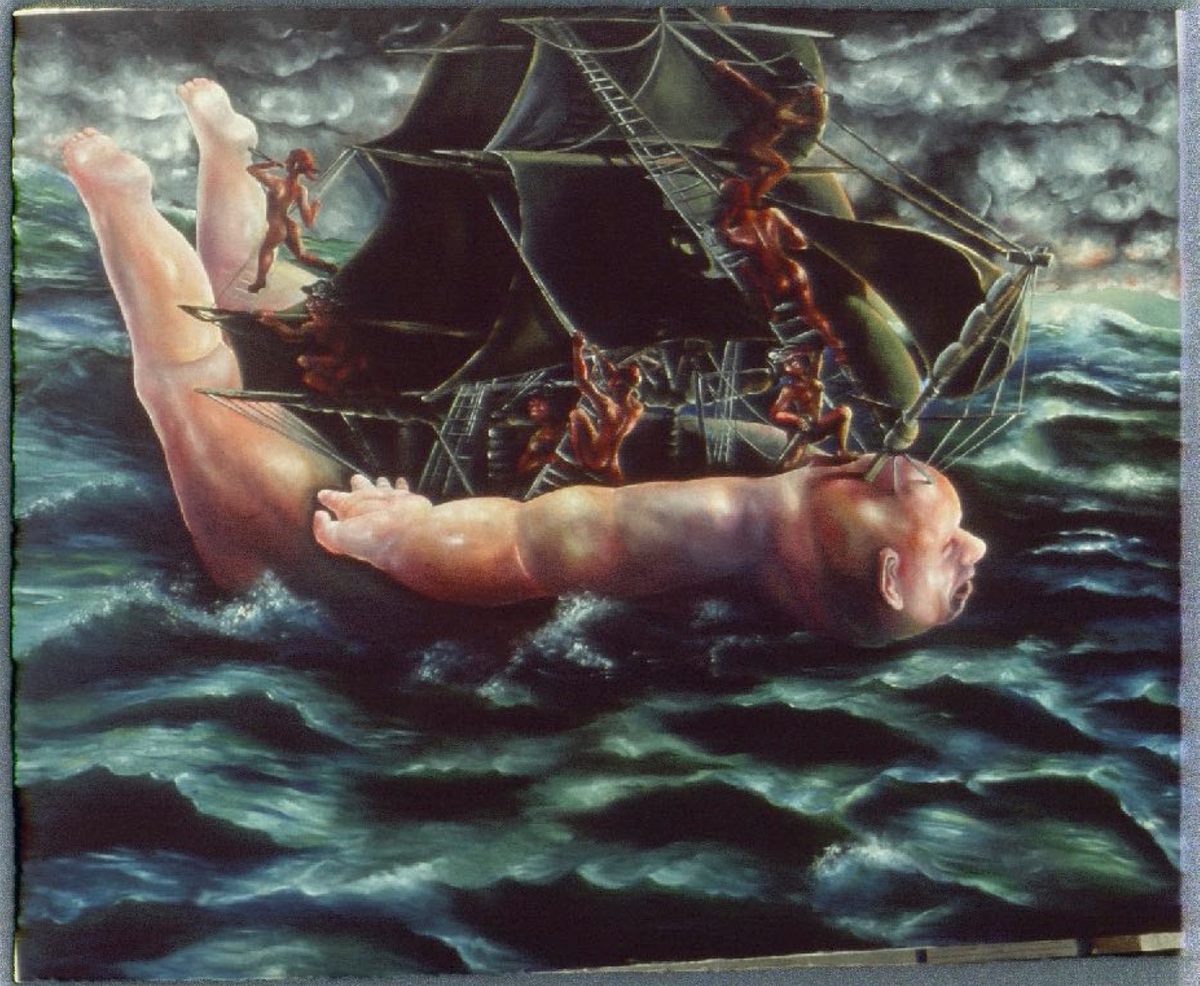

“We were kind of scared,” Turner said. “We didn’t know what to expect.” They had put out a call for “art against the oppressors” and collected pieces that dealt with “rage against sexism and the personal and societal oppression of women.” Rattle Your Rage opened at Filmmakers Gallery in Chicago in March 1990, on International Women’s Day, but before the show began someone smashed the venue window with an iron pipe (left behind at the scene) and the director of the space had a bomb set off at her house. One of the Sister Serpents wore a bulletproof vest to the event.

But the show went off without an incident and traveled to New York later that year. Within a year of its founding, Sister Serpents had women organizing demonstrations, creating reading groups, and doing all manner of other political work under the Sister Serpents banner. The idea was that everyone could work on whatever they wanted to. (The only requirement/gentle request: Help poster.) “This was a terrible plan,” Turner said. The group’s founding members feared their original message was being diluted. They didn’t just want to rage against men. “We wanted to be outrageous in order to be heard.”

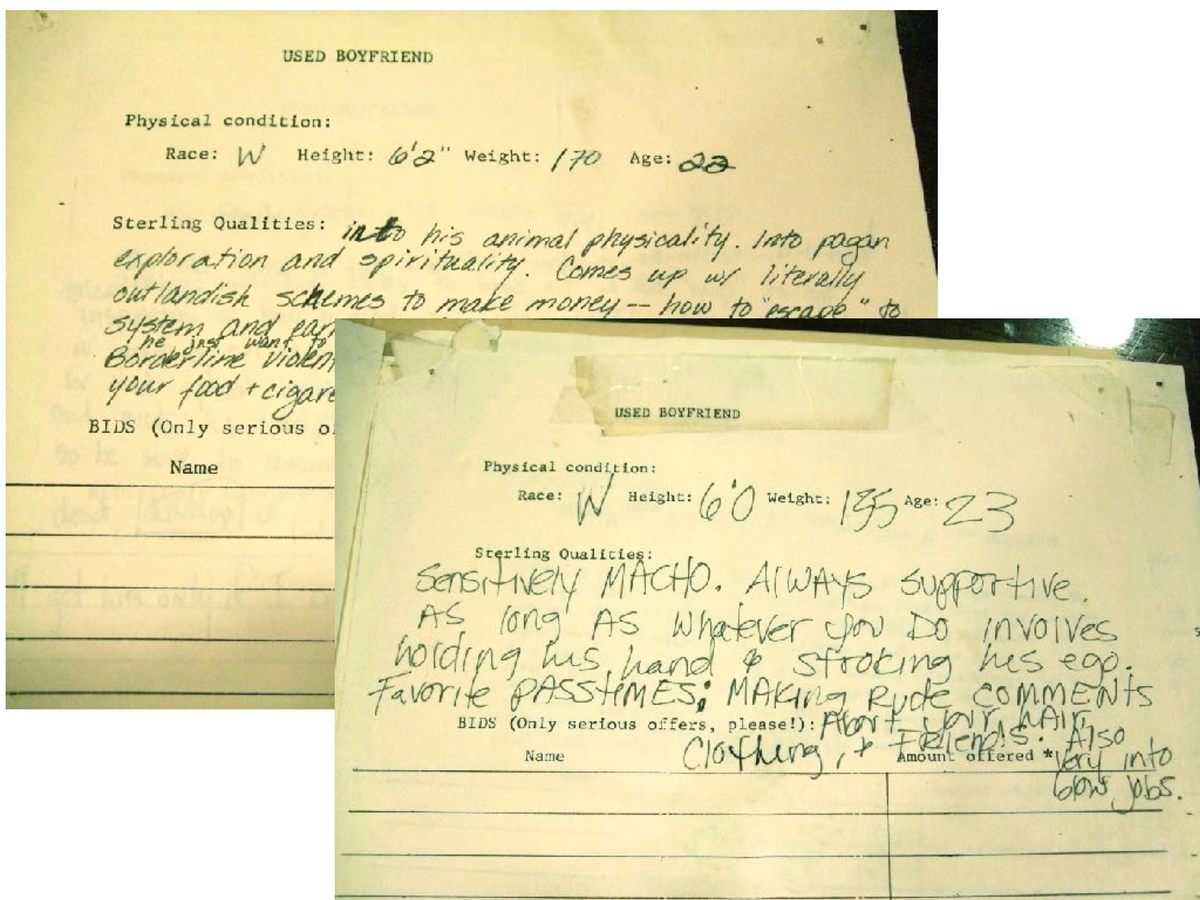

For another few years, Sister Serpents continued to stage art exhibitions that pushed the boundaries of societal norms—with a sense of humor. At one show, they created carnival-like cutout boards: a dinosaur for males and a snake for females. They held a “used boyfriend auction,” where they had plenty of offerings and very few takers. They continued to make posters and T-shirts, in addition to more ambitious art on the same themes of oppression and power. One recurrent motif was household scenes turned macabre, such as a nursery strewn with dirty diapers or a kitchen with a man’s head in the oven. Some of their work—American flag penis piñatas, for instance—Turner now finds “embarrassing,” she said at the Interference Archive. But one of the group’s other leaders, Chicago-based artist Mary Ellen Croteau, disagreed. “I don’t find them embarrassing,” she said. “I love the ideas that came out this group.”

Over time, the women sustaining the group turned to other projects and the profile of the once-notorious group faded. The Interference Archive has collected images of some of their work, along with press clippings, but little of it is preserved online, or at all. “So much was not photographed,” Turner said. “No one had cameras, no one had phones with video cameras.”

This art was controversial in the 1990s. Turner and Croteau expect that it would still be controversial today, perhaps even more so. The issues they were trying to address, of oppression and male power, are as raw and relevant as ever. Today, controversial images tend to fly through social media quickly, though. “You don’t see them on walls,” Turner said. “That’s different from when people walking the street would be confronted with our fetus poster.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook