The Story of the ‘Portofess,’ the Prank Confessional Booth at the 1992 Democratic Convention

Artist Joey Skaggs fooled everyone and pedaled off.

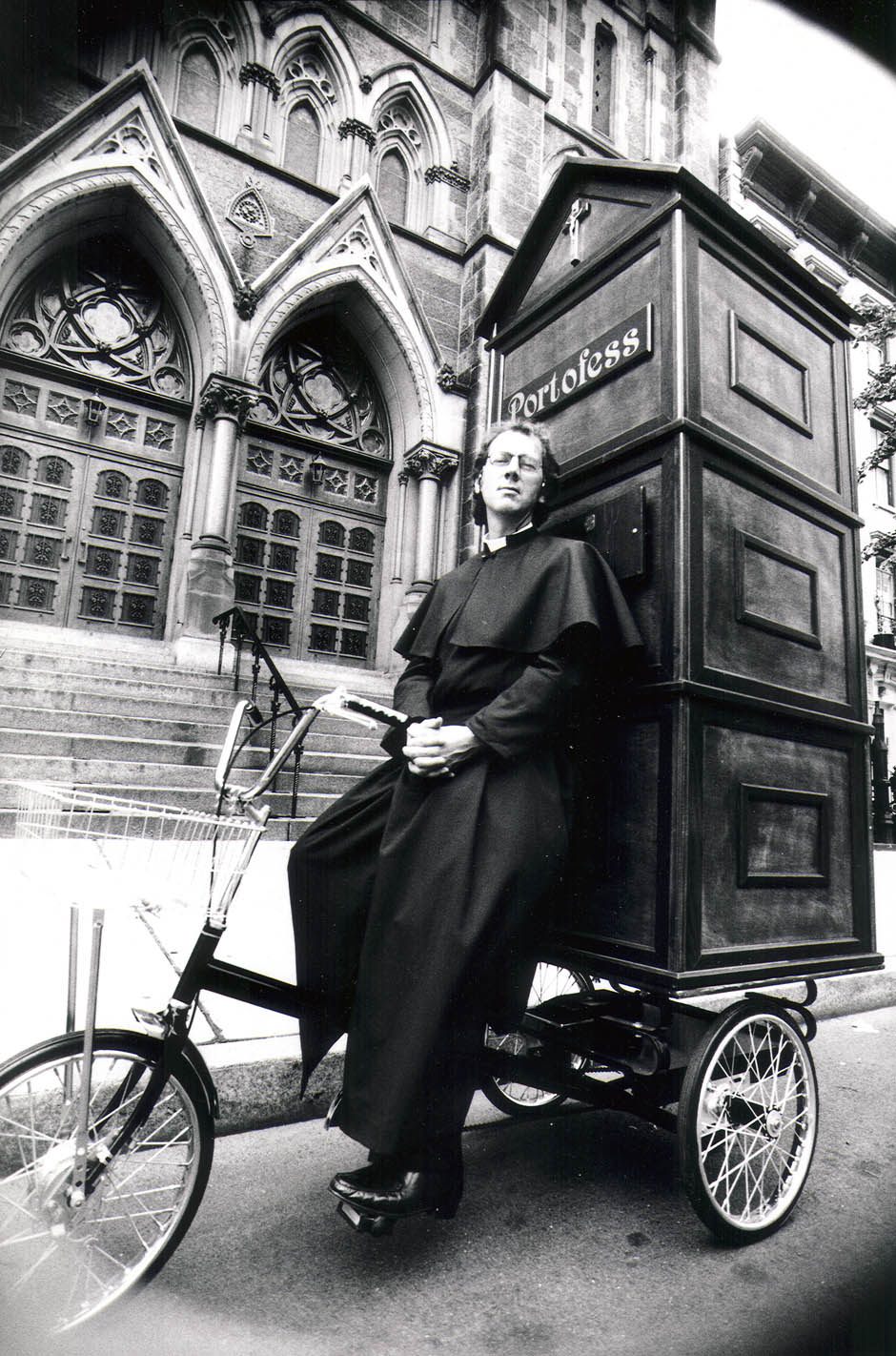

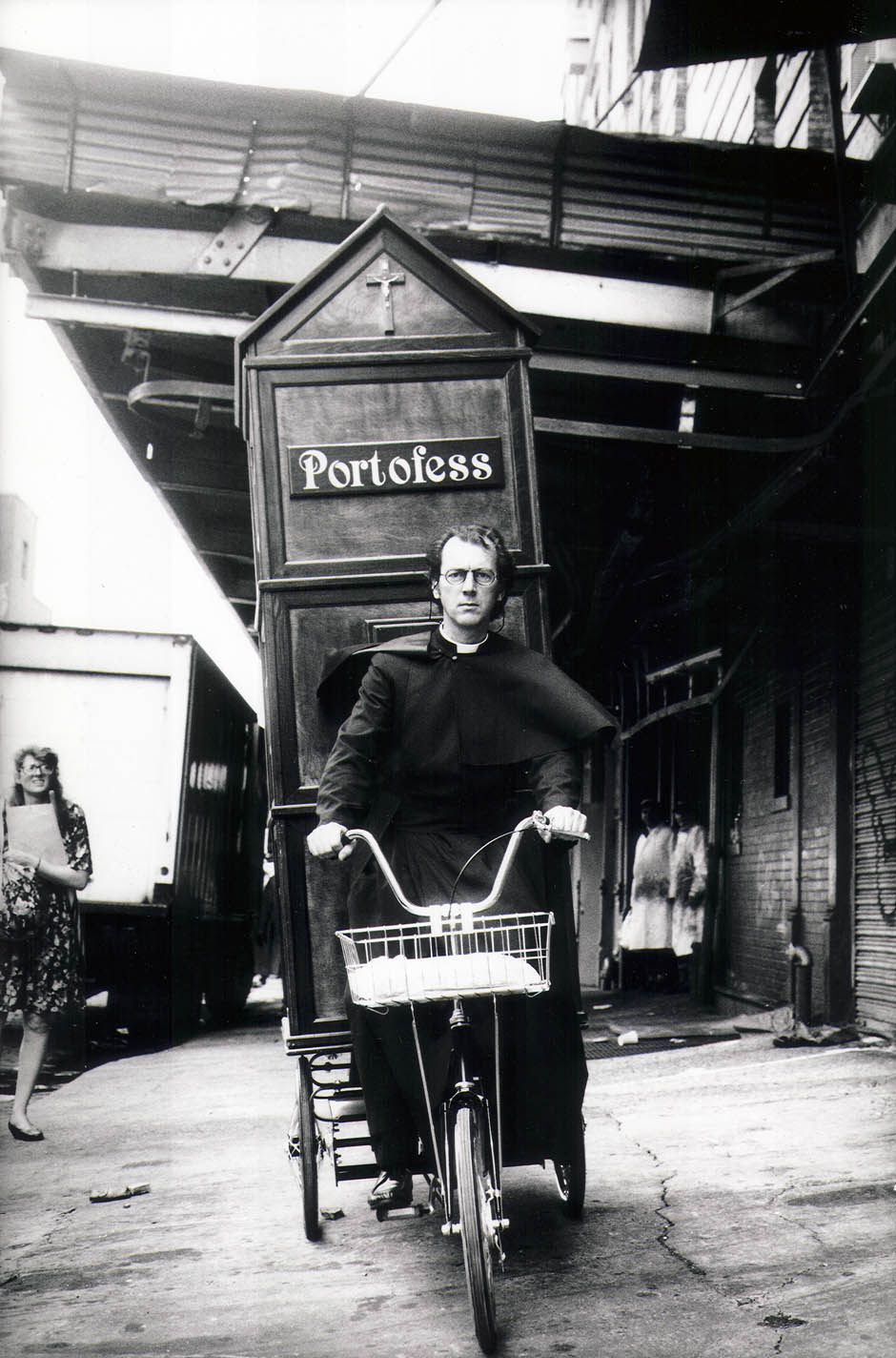

At 1992’s Democratic National Convention, a Dominican priest showed up on a tricycle. Attached to the back was a confessional booth, with a sign that read “Portofess.” The priest said he biked to New York, where the convention was held, all the way from California. The church, according to the priest, needed to take a “more aggressive stance and go where the sinners are.” He was ready to take confession from any politician who wanted or needed it.

The Portofess made papers all over the country. But soon enough Reuters revealed that the Archdiocese in California had never heard of this priest, who called himself Father Anthony Joseph or, sometimes, Father William. All other efforts to find him after the convention failed, as well, because he wasn’t a priest at all, but a character conceived by artist and activist Joey Skaggs, who has perfected the art of pranking the media.

Skaggs’s works include “Fish Condos” for upwardly mobile guppies, “Santa’s Missile Tow,” which featured Santa and his elves bringing a missile to the United Nations, and many other sculptures and performances. He talked to Atlas Obscura about what it took to create the Portofess and what reactions he got from the police, protestors, and the public.

Back in the early 1990s, where did the idea for the Portofess originate?

Well, I’ll go back before the 1990s. If you look at my career, beginning in the early ’60s, I was adamantly opposed to the war in Vietnam and the hypocrisy of the church. I was raised both from an Italian Roman-Catholic mother and a Southern Baptist father who met in New York. I was raised as a schizophrenic, from the Catholic side to the Baptist side and rejecting all of it. My work reflects not accepting doctrines I was brought up with.

If you’re going to make spectacles, you’re going to have to be mobile. The police will try to get you. But if you’re pedaling around, it’s easier to get to the site or many sites and to move on. The confessional booth fit into my criteria for a mobile spectacle. It was making commentary—I hoped it made commentary on everyone’s willingness to confess to Oprah or Geraldo or Sally Jesse Raphael. I had actors come up to confess and the public—once well- primed—the public lined up to confess. I couldn’t keep them out.

Did the actors actually confess?

The actors were just shills! I of course had to bone up on confession and how to forgive. I bought a bunch of Catholic textbooks, so I could sound authentic. Someone actually confessed to murder, and I didn’t know what to do and what my responsibility was. I told a detective, and he said, “What can we do? Maybe he’s pulling your chain.” That person was a total stranger. I told him, “Don’t do it again?”

What do you even do in that situation?

Just hope he doesn’t have a gun and doesn’t come back when he finds out you’re a prankster!

How else did you prepare?

I was traveling in Italy and sketching confessionals there and in New York. The booth had to fit in and out of my studio on Waverly Place, near Washington Square Park. I had to get a tricycle that would hold it. I went to a tricycle company in Long Island and told them I need a bike that has a platform that can hold 500 pounds and has solid rubber tires—I didn’t want to get a flat. They custom-made it. Then the problem was, where do I park it? None of the parking lots in New York wanted to take it.

I built the booth in Hawaii, where I had a house, and shipped it to my studio in New York! I had to bolt it all together in the streets in my priest outfit and then pedal it to the convention. Then I had to have people watch the booth or bring me drinks or be ready to pedal the tricycle away if I were arrested.

How did you come up with the name Portofess?

It’s like a Porta-Potty. But a confessional. The name was obvious to me. The names I come up with—it’s like I could write headlines for the New York Post.

So then you biked up to the DNC.

There are thousands of journalists there, waiting for action. They’re hungry for something. I had a professional furniture maker spray the booth so it looked well finished. I had a fine craftsman working with me. It wasn’t a refrigerator box on the back of the tricycle. I had a beautiful full priest outfit—I was walking down Broadway, and saw a priest outside a church. I asked him, “Excuse me, Father, where do you get your threads?” He invited me in and showed me the catalog they used to order all their clothes. He said, do you want one? I’ve got extras here. I ordered the whole outfit from there.

Everything is in the detail. I’m very detail-oriented because that’s what’s convincing. The sculpture looks beautifully well made. I had glasses on, and I just looked the part of a priest. Of course, I had friends who would come and step into the confessional booth and tell me dirty jokes. I had a tape-player playing Gregorian chants. I had a little flyer to hand out, saying “Religion on the move, for people on the go.” I had a little basket on my tricycle in the front and people—especially journalists—reached in to take that. I said I had pedaled all the way from California. The story and the visuals were too good. With Clinton running it was a juicy situation, to hear confessions of the politicians.

Some of the hoaxes take a lot of time, two years. Some have to be nurtured. Every one is a different challenge, and I like that. I’m an artist; that’s what I do. This is my artwork. It’s not like I’m a joker. It’s written, produced, directed staged, acted, and documented. It’s a very complicated, complex process. It’s like doing a film or a theater piece without the stage.

What were some of your favorite reactions to the booth?

I was attacked by militant feminists who were pro-abortion, and they had bright yellow stickers that said, “I fuck to cum, not to conceive.” They slapped one on me, and on the confessional booth. For the first time in my life, the police came to my rescue. I’ve been taken away by the police so many times. But now these good Catholic Italian and Irish cops were going to come to save the priest. I didn’t know where my enemies were coming from—would it be irate police, irate Catholics, irate pro-abortionists? It was a day of conflict, which is what I love. I know it’s working when you have all these controversies and conversations and debates happening all around, which is what happened.

Why was 1992 the right moment for this piece?

I could have done it anywhere. I could have pedaled down to Wall Street and heard the confessions of the brokers, or gone to Washington and parked in front of the White House. That would have been a great commentary, as well. What the confession booth represents is powerful, and I had many other sites I could have taken it to.

Taking it to the convention meant that all I had to do was show up. I didn’t have to do any promo. The visual was so striking that all I had to do was appear. I always think about these things—do I need to put out a press release, do I need a brochure, do I need to put out an ad? What do I need to do to get attention for this? With the confessional booth I didn’t have to do anything, and I could pedal away.

Steve Powers from Fox News loved me, he considered me his good buddy. He had interviewed me many times. At the convention, Steve Powers comes running up to do a story. I thought—“Oh no, and I start to pedal away.” I’m waiting for him to say, “Joey Skaggs, you son of the bitch, I got you.” But the clothes made the man. He saw the priest, and that was the story. I was so shocked that he didn’t recognize me. You are not an individual person, you are a subject, and they suspend critical analysis for wishful thinking: “This story is too good.”

To watch it firsthand, to be the instrument of it, it’s bizarre to see how it works like that.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook