Found: A Letter From Frederick Douglass, About the Need for Better Monuments

It was discovered “forensically,” thanks to Douglass’s distinctive usage of an unusual word.

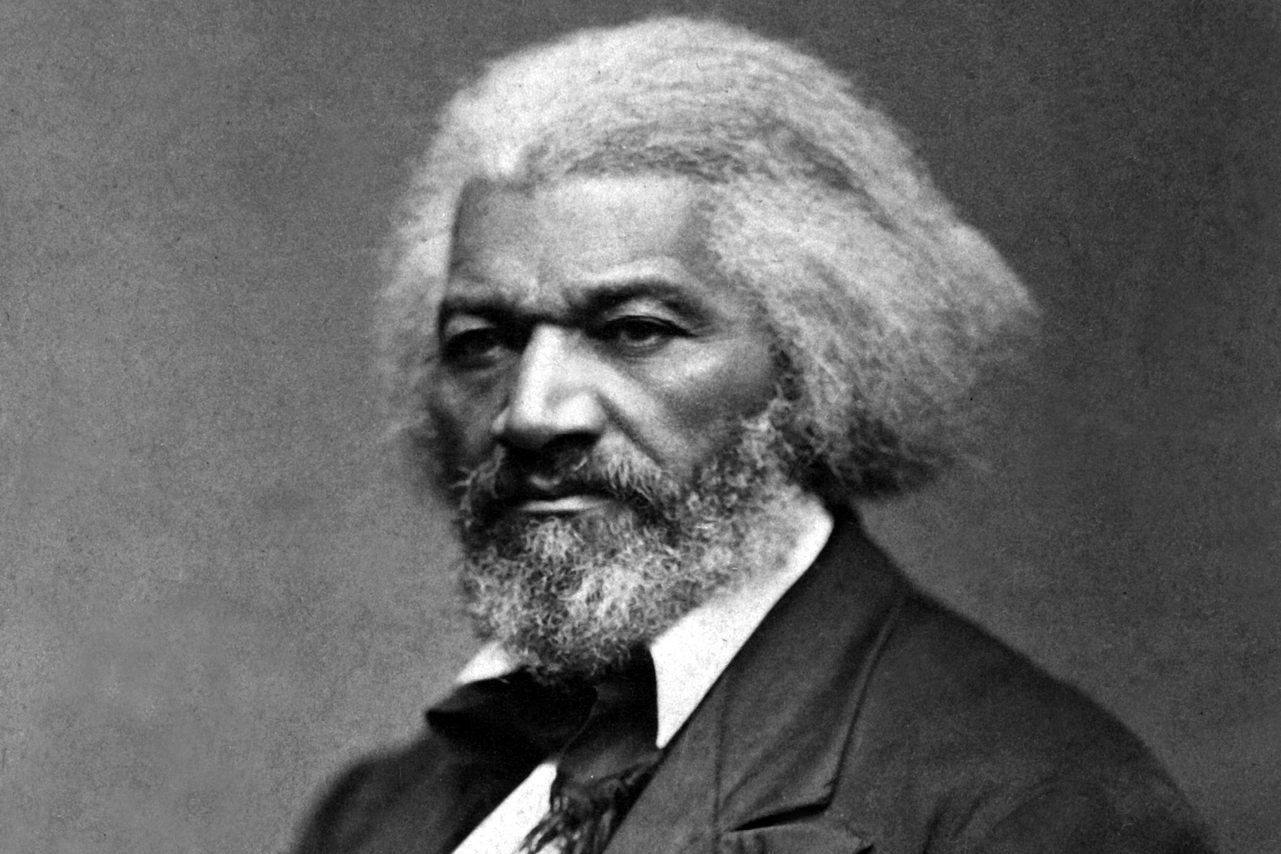

The debate over historical monuments currently roiling the United States is, in fact, nothing new. Back in 1876, none other than Frederick Douglass himself took issue with a Washington, D.C., statue of Abraham Lincoln, which activists are now lobbying to have taken down. Only now, however, do historians have proof of what Douglass thought of it when it went up.

The statue in Lincoln Park, known as the Emancipation Memorial, depicts the 16th president beside a Black man who, depending on how you see the piece, is either kneeling or rising. It’s supposed to commemorate the end of slavery—but in any interpretation, the Black man is physically lower than Lincoln himself, leading critics to see the statue as a paean to Lincoln’s generosity, and not a testament to Black Americans’ own roles in their liberation. “Statues teach history,” says Glenn Foster, an activist with the Freedom Neighborhood, who wants to see the statue removed. The Black man in this statue “is in a very submissive position,” he says, adding that that’s not “respectful to our community, or to anyone in general.”

As The Wall Street Journal reported, two historians, Scott Sandage of Carnegie Mellon University and Jonathan White of Christopher Newport University, were recently debating what ought to be done with the statue, and they wanted to know whether the social reformer and statesman Douglass had, in fact, criticized it directly. Douglass died in 1895, but posthumous reports of his comments on the subject have been circulating since 1916, when a book stated that he had been critical of the statue at its unveiling. In his prepared speech for the event, Douglass challenged the nascent Lincoln mythology, calling him “preeminently the white man’s president …,” but it wasn’t clear whether, in an alleged aside, he also criticized the new statue itself. The two scholars disagreed over the account’s reliability, so Sandage set out to more firmly establish the abolitionist’s position.

Sandage searched a digital newspaper archive for reports on Douglass from 1876, when the statue was dedicated. He turned up a wide variety of results, but even the most helpful ones seemed incomplete. They were essentially a series of headlines repeating, “Frederick Douglass Says,” followed by short blurbs that relayed Douglass’s words on the subject out of context, focused on this provocative sentence: “What I hope to see before I die,” wrote Douglass, “is a monument representing the negro, not couchant on his knees like a four-footed animal, but erect on his feet like a man.”

To Sandage, this choice of excerpt spoke volumes about the newspapers’ intentions. Out of context, the sentence could, at the time, have characterized Douglass as a whining agitator. Contemporary readers may have laughed, “Ha ha ha, isn’t that funny? He’s still not satisfied. He still wants another statue,” Sandage explains. Worse, he adds, by isolating Douglass’s description of the Black man on his knees, the papers printed the blurbs as “race-baiting comedy,” and as a kind of “little minstrel show.” So it seemed that Douglass had indeed criticized the statue, but Sandage sensed the full story was deeper.

Sandage’s “forensic strategy” was to zero in on the most striking, unusual word in Douglass’s quote: “couchant,” meaning “lying down especially with the head up,” according to Merriam-Webster. “If you were to give a guess,” says Sandage, “of how many times, in the last 500 years of typographical human history, the words ‘Lincoln’ and ‘couchant’ were used in proximity to one another, a good guess might be: ‘One.’ So that provides a really good hook for searching.” Isolating single words or word combinations like that has helped to unlock other historical literary mysteries, adds Sandage. For example, researchers discovered that Lincoln’s “Letter to Mrs. Bixby” was ghostwritten by John Hay because it contains the word “beguile,” a word that doesn’t appear in the 16th president’s other writings.

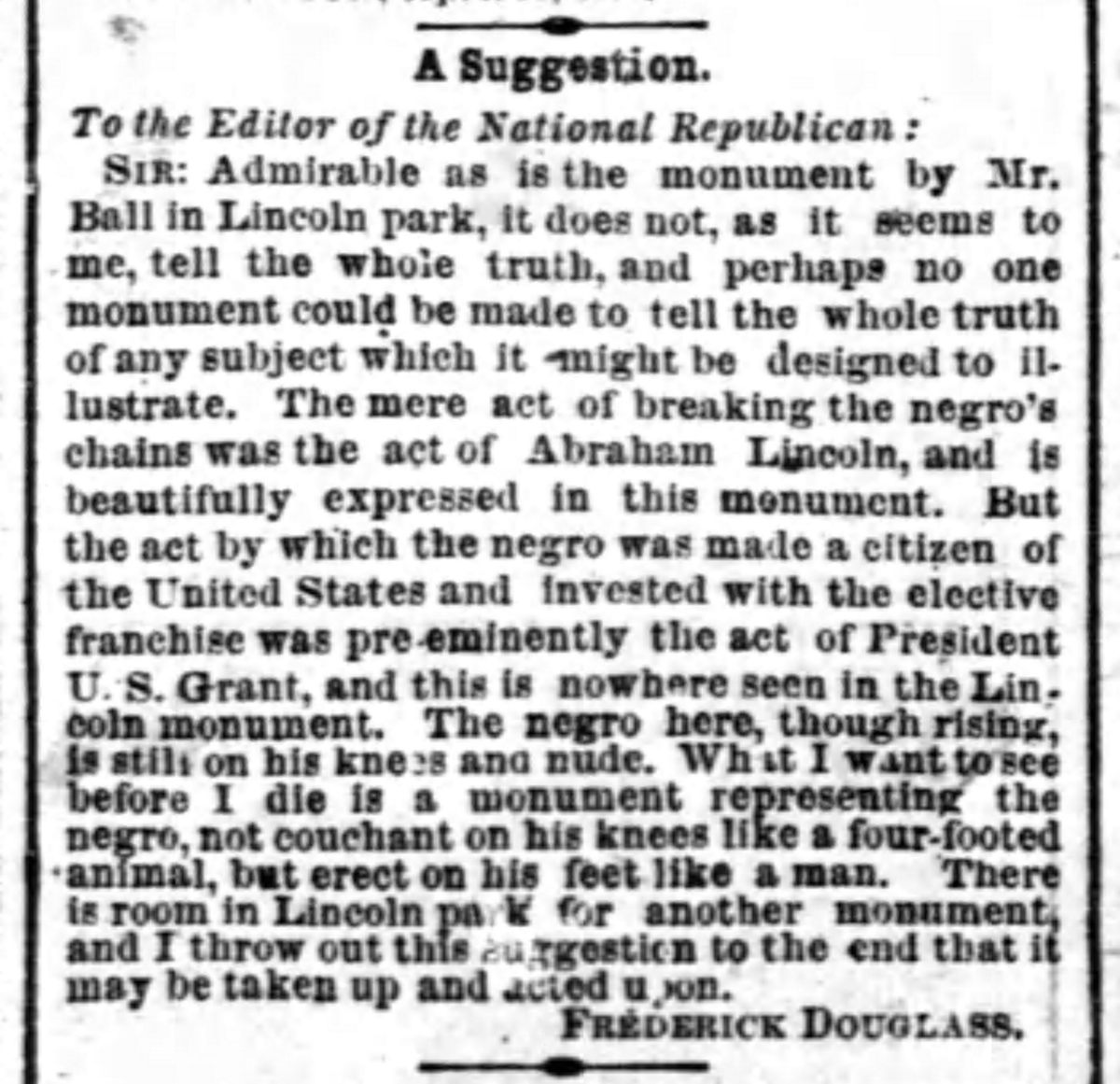

Using “couchant” as the keyword in his search—and experimenting with a few combinations of other words—Sandage identified three newspapers that ran the entirety of a letter Douglass wrote about the statue, a few days after speaking at its dedication. “Admirable as is the monument by Mr. Ball in Lincoln park [sic],” writes Douglass, “it does not, as it seems to me, tell the whole truth …” He credits Lincoln for following through on emancipation, but adds that “the negro was made a citizen” by “President U.S. Grant,” under whose administration the Fifteenth Amendment was ratified. (In theory, the Amendment enfranchised Black men with the right to vote. Of course, enforcement of that right has been a long-standing issue.) He concludes by suggesting that “[t]here is room in Lincoln park for another monument,” and that that space ought to be filled out with works that could help complete the historical picture.

In fact, Lincoln Park received a second monument in 1974, of Black American educator Mary McLeod Bethune. In a recent essay for Smithsonian magazine, Sandage and White proposed that the park could be filled out with an “Emancipation Group” of statues commemorating figures such as Douglass, Archer Alexander (the model for the emancipated person in the existing memorial), and Charlotte Scott, the formerly enslaved person who raised funds for the Emancipation Memorial and contributed its first five dollars. (A plaque by the statue explains that it was funded entirely by formerly enslaved people.) As Douglass wrote, the Lincoln statue does not have to come down for these to go up, but if it ultimately does, Sandage says, it “would be no loss whatsoever to the memory or reputation of Abraham Lincoln.” He’s got another, way bigger memorial after all.

Glenn Foster, meanwhile, says he’d like the monument to be replaced outright, ideally with a statue honoring a Black female historical leader from the Washington, D.C., area. He appreciates the legacy of Frederick Douglass, but adds that societal understanding of race “changes over time,” and that in the 19th century, it would have been hard for Douglass “to speak out against Lincoln.” In 2020, he adds, “we don’t have to accept having Lincoln as the savior of all Black people,” while Douglass “really didn’t have other options.” (Recently, Boston announced that its replica of the Emancipation Memorial will be removed.)

Ultimately, it may never be clear if Douglass actually criticized the statue at its dedication, or if his critique first emerged days later, in the follow-up letter. Either way, the search for more undiscovered Douglass writings goes on. Keep an eye out for unusual words in his (or anyone else’s) writings, because, as Sandage says, “these databases need to be used ‘forensically,’” not to solve crimes exactly, but to get at historical unknowns. To anyone wondering whether there are “other letters written by Frederick Douglass that we don’t know about,” he says, the answer “is almost certainly ‘Yes.’”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook