How Lady Bible Hunters Made the Victorian Era’s Most Stunning Scriptural Find

Paintings of Scottish twins Agnes Smith Lewis (left) and her sister Margaret Dunlop Gibson. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Scottish twins Agnes and Margaret Smith were the last people you’d expect to discover one of the earliest known copies of the gospels, but in a dusty closet in an Egyptian monastery in 1892–without a university education or formal language training between them–the God-fearing twins uncovered the Syriac Sinaiticus.

The latter half of the 19th century was a time of huge anxiety of the Bible’s veracity, and the importance of such a find cannot be overestimated. Overnight, the newspapers turned the middle-aged sisters into public figures, much to the chagrin of the leading Biblical scholars who had dreamed of making such a find for decades.

Born in 1843 and raised by their father, the twins were inseparable from a young age. And they were privileged: Educated as if they were boys, for every language they learned, the girls would be taken to that country by their father. And so it was that the twins had mastered French, German, Spanish, and Italian by their teens.

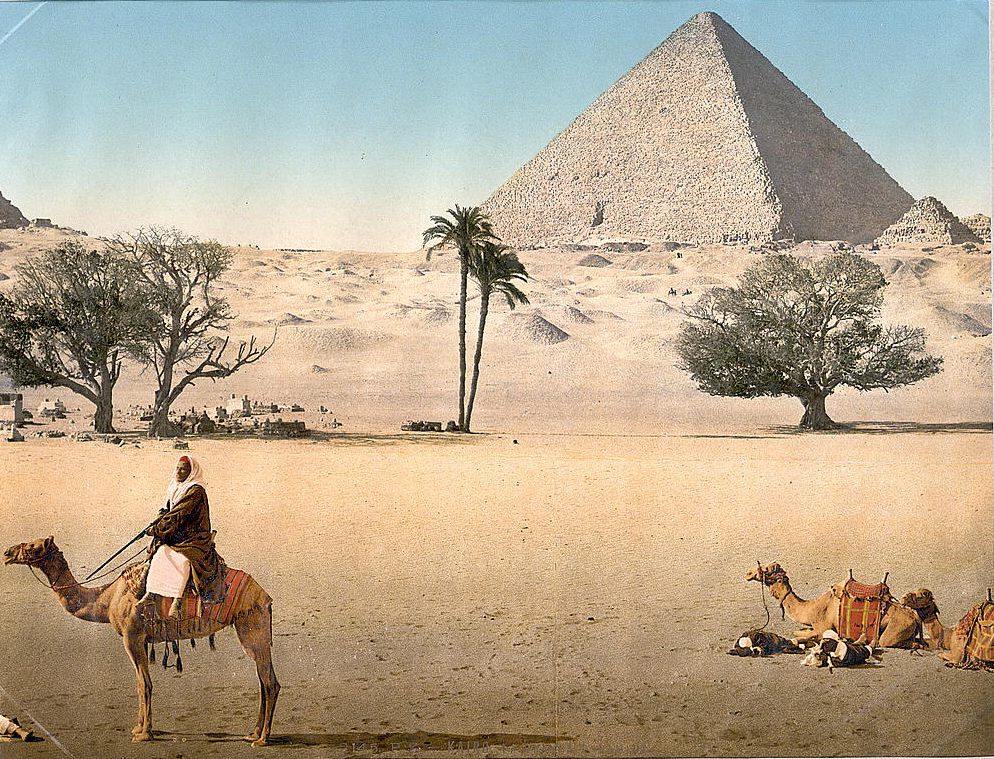

A photochrom of Egypt in the 1890s. The sisters traveled to the Sinai Desert in 1892, by camel. (Photo: Library of Congress)

The twins’ father died when the sisters were 23, and they received a huge inheritance of about a quarter of a million pounds. Alone in the world and now exceptionally wealthy, the young women took a trip–not to fashionable Paris or the Italian Riviera–but to Egypt. As would become characteristic of the women, they refused to follow the mores of the time: Instead of having a male chaperone, they let themselves be accompanied only by a young female teacher.

This was hardly a pleasure trip–dysentery, cholera, and other infectious diseases were rife, and at points the twins did not know if they would return from their journey down the Nile. The voyage was a small disaster; they were supposed to visit various religious sites along the route, but their dragoman, Certezza, kept the sisters as virtual prisoners on the rat-infested sailboat he’d convinced them to rent. Following the river trip with a visit to Jerusalem, the sisters were in the Middle East for nearly a year.

Back in Britain after their adventure, the twins dedicated themselves to mastering more languages, including ancient and modern Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, and Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic.

The twins settled in Cambridge in 1890. Even though the university was barred to women students, the scholarly city should have been a perfect spot for these self-taught linguists. However, Janet Soskice, who wrote the seminal biography of the twins, The Sisters of Sinai: How Two Lady Adventurers Discovered the Hidden Gospels, notes that the insular Cambridge set cast the twins as outsiders with their gaudy home, their lack of husbands, their expensive dresses, bonnets and private coach. The twins’ eccentricities, like exercising in the back garden in their bloomers, didn’t help.

But they eventually shed their ‘spinster’ label: Margaret married a renowned Scottish minister named James Gibson when she was 40; Agnes married the Cambridge scholar Samuel Savage Lewis four years later, in 1887, a match that helped the women’s entry into Cambridge society. Tragically, both men died after just three years of marriage.

St Catherine’s Monaster in Egypt. (Photo: Joonas Plaan/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

Once again, the twins only had each other, and so in 1892 they decided to venture to Egypt’s Sinai Desert, armed with a tip from the Cambridge-based orientalist James Rendel Harris to search out a dark closet off a chamber beneath the archbishop’s rooms at St. Catherine’s–perhaps the world’s oldest Christian monastery –where there were chests of Syriac manuscripts that Harris had noticed but hadn’t been able to inspect on his last trip to the monastery.

They were all hoping these manuscripts might contain early versions of the gospels, as the western Christian world was clamoring for finds that could disprove some of the questions Darwin had raised about the veracity of the Bible.

And so Agnes and Margaret Smith braved an area where, ten years before, Cambridge’s leading Arabic professor was murdered by bandits. Together with their guide, a Syrian Christian called Hanna, and 11 Bedouin helpers, the sisters rode temperamental camels and camped in tents for weeks on end–no small test for two wealthy women used to living in luxury.

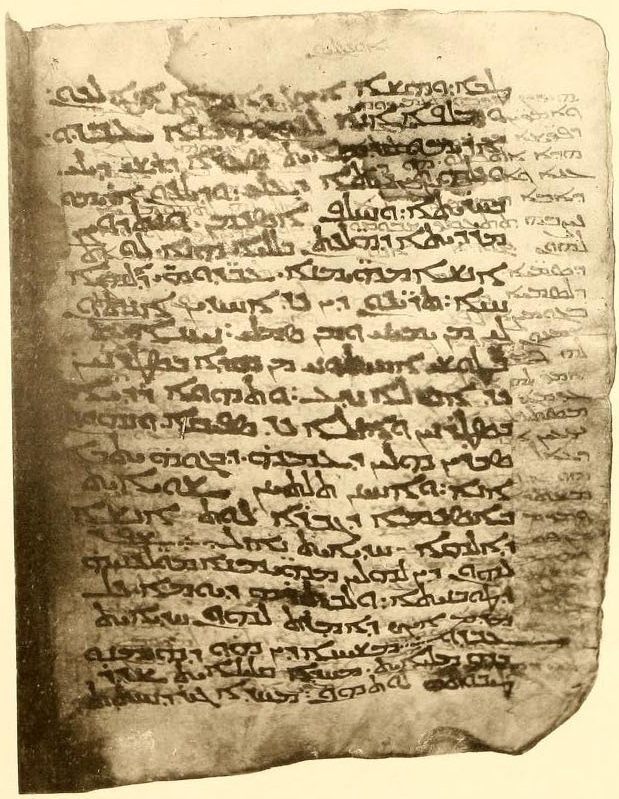

A page from the Syriac Sinaiticus, discovered in St Catherine’s Monastery, Egypt, in 1892 by the sisters. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Agnes had been learning Syriac–a branch of Aramaic, the language Jesus would have spoken–in the six months before the trip. Just as well, because she managed to do what so many male professors and scholars had failed to do in their searches of the monastery–she found what appeared to be an ancient manuscript of the four gospels.

The twins couldn’t be sure of their find, but nevertheless they were convinced enough to use almost all of their film on photographing the palimpsest.

Back in Cambridge, when they tried to show the photographs to the university’s eminent professors, they were ignored as dilettantes…until the professors got a proper look. It looked like Agnes Smith really had discovered something of worth. Yes, the Syriac Sinaiticus dated back to the mid-4th century, and the translation it preserved went back to the 2nd century, very close to the fountainhead of early Christianity.

A group of scholars, including three world-class transcribers–Professors Robert Bensly, Francis Crawford Burkitt, and Rendell Harris– was hastily put together to go back to the monastery and transcribe the manuscript.

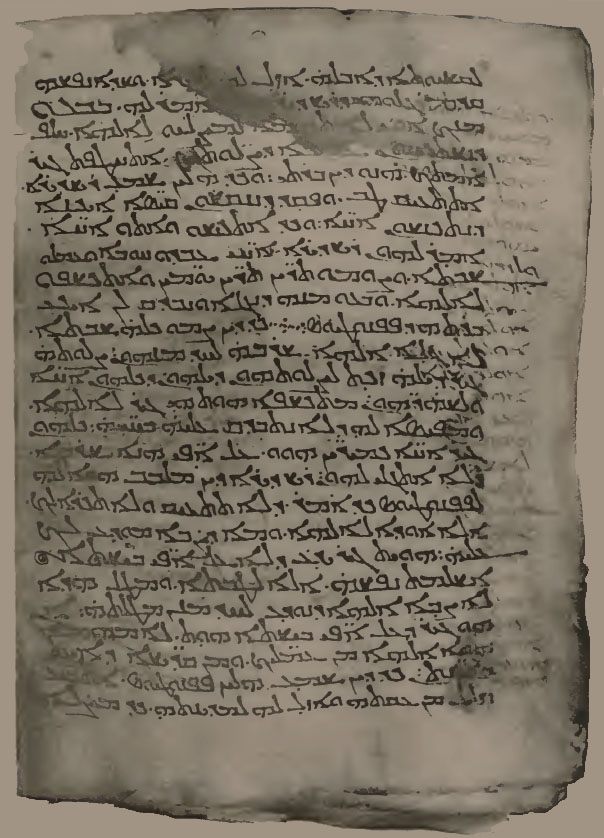

Another page from the Syriac Sinaiticus. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Everyone on that trip expected to leave the Sinai to a burst of fame and glory, but the newspapers only had eyes (and column inches) for these eccentric twins who’d come out of nowhere. Bensly and Burkitt were livid–they saw the women as uneducated upstarts who had stolen their claims to fame. Sure, the male professors did not dispute that Agnes had physically come upon the manuscript, but they refused to credit her with much more.

While the men stewed, the twins became public figures who were finally accepted into scholarly society: There were invitations from eminent professors across the country, and honorary degrees from St Andrews and Heidelberg, Trinity College and Halle.

Margaret died in 1920, and Agnes in 1926. During their lifetime, the University of Cambridge never recognized the sisters for their monumental scriptural find of the Syriac Sinaiticus. But that isn’t wholly surprising from a university that denied women full degrees until 1948.

Update: In an earlier version of this story, we stated that Aramaic was a branch of Syriac. It is the other way around; Syriac is a branch of Aramaic. In one instance, we misstated the year that the Syriac Sinaiticus was found. It was discovered in 1892, not 1859. We regret the errors.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook