The Many Lives of Maria Rasputin, Daughter of the ‘Mad Monk’

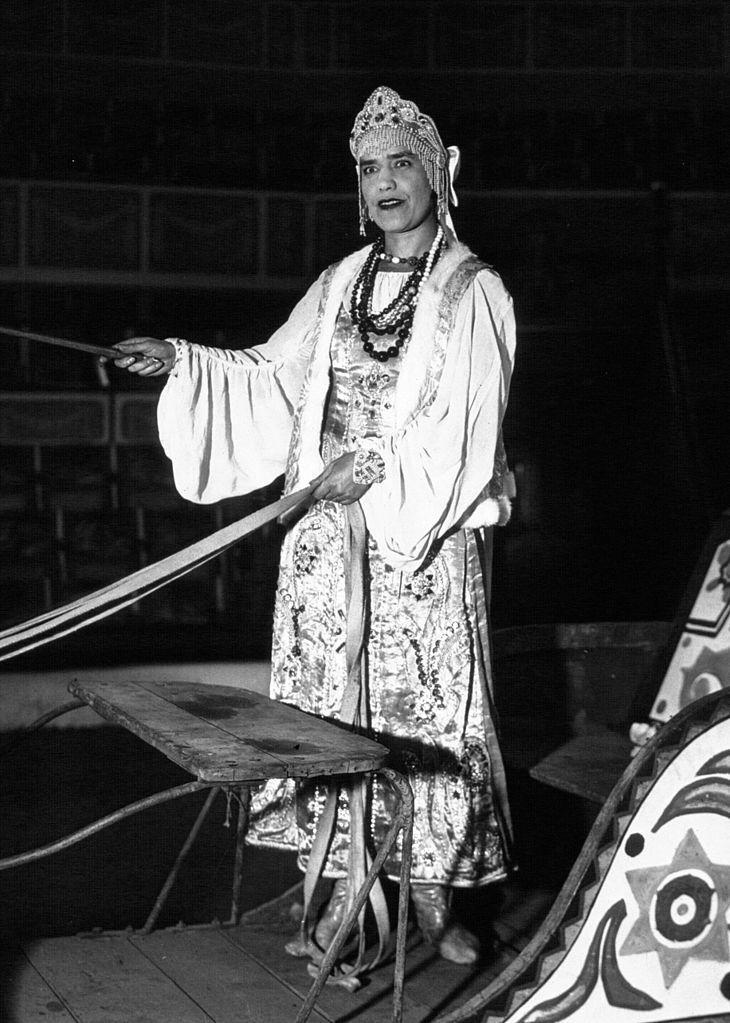

Maria Rasputin as an animal trainer at a London circus in 1934. (Photo: Planet News Archive/Getty Images)

I was born in 1899 in the village of Pokrovskoe in the county of Tobolsk. My parents are peasants, simple people. Our family consists of: father, mother, grandfather (my father’s father), my brother, sister and myself. We all live happily together but sometimes I get cross with my brother and sister, but with my sister I get cross all the time. My father plays an important role because the Sovereign knows him and loves him.”

Maria Grigorievna Rasputin wrote the simple words above as a young teenager in unpublished diaries. But from the beginning of her life in rural Siberia to its end in sunny Los Angeles, nothing about Maria’s life would ever be simple or easy.

Maria spent her early childhood in a relatively well-off family of peasants. Her mother was a practical, hardworking woman. Her father Grigori, was a Starets, an un-ordained holy man who traveled the country preaching and comforting those in need. From the start, Maria seems to have had a healthy sense of skepticism. She and her brother and sister dreaded the long hours of enforced prayer and fasting “for which everything, anniversaries or penitence’s, served as an excuse.”

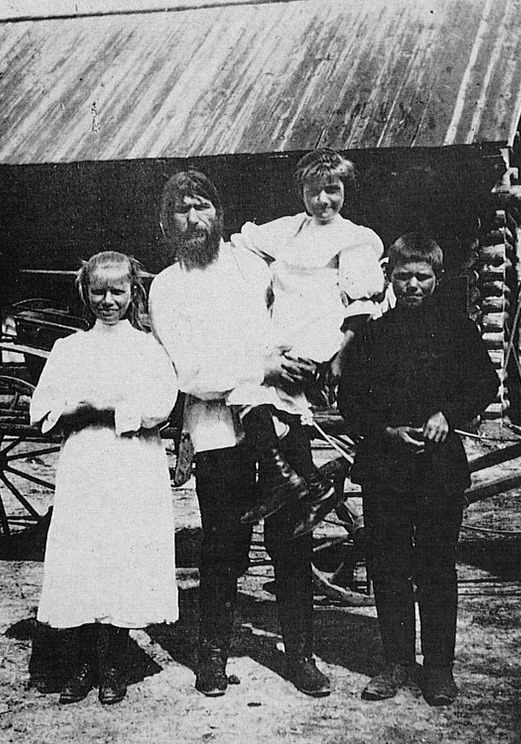

In 1906, the family’s life was transformed when Grigori, who would become known to history simply as “Rasputin,” was introduced to the royal family in St. Petersburg. He was soon credited by the Empress Alexandra for saving the life of Alexi, the hemophiliac heir to the Russian throne. In 1910, Maria and her sister, Varvara, were sent to live with their father in St. Petersburg so that they could be transformed into “little ladies.” Her mother had no interest in big city living and stayed in Pokrovskoe with her son. Since their father was busy with royal and other duties, their longtime family servant (and Rasputin’s reputed mistress) was tasked with the children’s care.

“She found a governess to look after us and take us out, and helped us to make up for lost time by making good the considerable gaps in our early education,” Maria remembered. “Alas! It was a hard task, hard for her without any doubt, but hard also for the two little savages whom she tried to make into young ladies!”

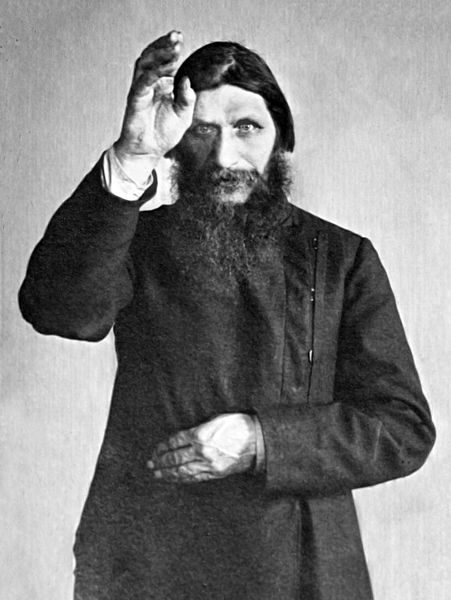

Rasputin, c. 1914. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Maria eventually settled into life in Saint Petersburg and became her father’s unofficial hostess. As Rasputin’s influence grew, visitors (mostly women) came to their small apartment all through the day and night waiting for their chance to meet with the mystical and powerful “little father.”

To Maria, Rasputin was just an unsophisticated, simple man with magnetic clear blue eyes, beautiful long hands, and a peasant’s belief in the power of prayer. In her memories he was a strict father, blessing them every night before they went to bed, and making sure the girls were educated and pious:

We were never allowed to go out alone, rarely were we permitted to go to a matinee, and later on, when young men began to gravitate about us, he proved to be the strictest of mentors. None of them had a right to more than half an hour’s tete-a-tete; after that had elapsed, my father burst into the room and showed the poor lad the door. But what was not limited to half an hour was the length of time devoted to prayers! Every morning and night we prayed together. On Sundays we passed the morning at church, and the greater part of the afternoon in worship. My sister and I found these hours spent on our knees on the stone floor exceedingly long, though I must admit that the fashion of the time, with its long skirts, allowed us to cheat a little by clandestinely sitting on our heels when our father’s eyes were not fixed upon us!

However, there were dark undercurrents swirling around the little family. To most, Rasputin was more than just a humble holy man. He was a drunk, demonic, womanizing charlatan who had bewitched the deeply religious Empress Alexandra in her desperation to save her only son. Rasputin’s influence over the royal couple grew as the geopolitical situation surrounding the Romanovs grew more and more dire.

Rasputin and his three children, Matryona (Maria), Varvara et Dimitri. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Although Maria would admit in her old age that there were many things going on that she did not know about, at the time her life seemed charmed. She became friends with Nicholas and Alexandra’s four daughters, and would remember their grace–how they would enter a room at Tsarskoye Selo so quietly that one could not even hear their feet touch the ground.

But this fairytale life did not last long. Rasputin, who had become more of a drunk than ever, still insisted to his daughters that he would not have “people uttering the filth about you that they do about me.” Russia slid into domestic chaos, and brutal World War I fighting raged. Rasputin, “the mad monk,” became an easy scapegoat for angry aristocratic and revolutionary forces. One freezing December night in 1916, Rasputin, lured with the promise of a late night party, was murdered by Prince Felix Yusupov and his associates. A few days later Rasputin’s frozen body was found in the Malaya Nevka River. It is rumored that Maria had to identify the body of her father, which had been bludgeoned, shot and finally drowned.

Maria and her sister’s lives were transformed overnight. Maria noted bitterly that at his funeral, “Many places in the little chapel were empty, for the crowds that had knocked at my father’s door while he still lived to ask some service of him neglected to come and offer up a prayer for him once he was dead.” The Imperial Family stuck by the sisters, and they spent many hours at Tsarskoye Selo with the royal children. But, soon this safety net was ripped away as well, when the long brewing Russian civil war began. On her last visit to the palace, Maria remembered the cold but kindly Empress telling them, “Go my children, leave us, leave us quickly, we are being imprisoned.”

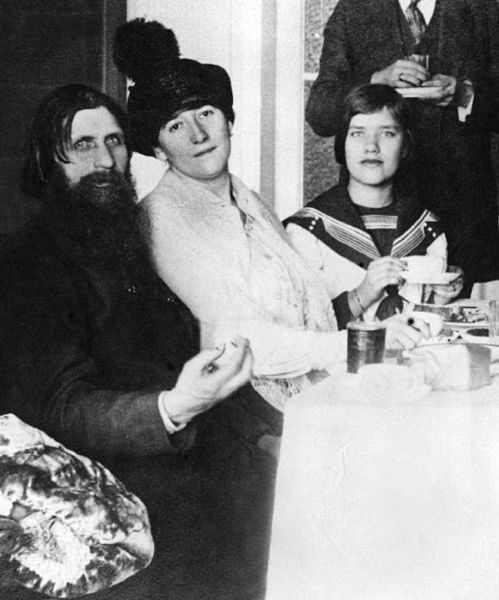

Maria and Varvara escaped to their mother’s home in Pokrovskoe. In 1917, Maria married her “dear friend,” Boris Soloviev, a man of questionable character who many considered her father’s successor. The couple lived a chaotic, fugitive existence, attempting to save the royal family from their imprisonment in Siberia, and constantly on the run from the Red Army. When Boris was imprisoned, Maria got him out of jail by bribing a guard with 1,000 rubles.

Rasputin with his wife and his daughter Matryona (Maria), far right, in 1911. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

They eventually escaped to continental Europe, wandering from “capital to capital,” living the nomadic existence common to many formerly genteel expatriates after the wars. Maria gave birth to two daughters, Tatiana and Maria. They settled in Paris, where Boris eked out a living as a soap factory worker, night porter and car washer. Boris died in 1926, according to Maria, “worn out with privations and the work beyond his strength that he accepted in order to preserve us from dying of hunger.”

Maria was alone, but at least she was alive. The entire family of Nicholas and Alexandra had been murdered at Yekaterinburg’s Ipatiev House, the “house of special purpose,” in 1918. Her mother and brother disappeared into the Soviet gulags of Siberia. Her sister, Varvara, died in Moscow in 1924–some said of starvation, others said of poison. But Maria soldiered on, supporting her daughters as a lady’s maid and companion to a rich Russian exile.

Then, Maria told the Los Angeles Times, “absolutely unexpected, I got offer to be cabaret dancer in Bucharest. This was because of my name, not because of my dancing.” For several years Maria danced across Europe, allowing herself to be billed as “the daughter of the mad monk.” In 1929, she published her first book, The Real Rasputin, a strongly worded defense of her father.

Soon Maria took on another career- that of an animal trainer in a traveling circus. With her characteristic sense of humor, Maria said: “They ask me if I mind to be in a cage with animals, and I answer, ‘Why not? I have been in a cage with Bolsheviks.’” She also published another book about Rasputin, 1932’s My Father. In it she said her reason for writing the book was not literary:

If I thought myself capable of undertaking a literary career I should not today be struggling to earn my daily bread as a trainer of wild animals…it is my desire to consecrate myself to a task, direct the whole of my life towards one goal, that of giving back to my father his true character.

Maria Rasputin as a circus performer in 1932. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

In 1935, Maria accompanied the Ringling Brothers Circus to America. “To come to America was my dream for many years,” Maria told a reporter for the Los Angeles Times. Americans were unsurprisingly fascinated by Maria, and papers across the country carried pictures of her with captions like, “European wild animal trainer and self-declared daughter of Russia’s ‘mad monk’ tries to hypnotize a circus elephant in Philadelphia.” She was also featured along with other Ringling Brothers stars on the back of a Wheaties box, extolling the cereal as “the breakfast of champions.”

Maria officially immigrated to America in 1937 (her daughters stayed in Europe) and gave up her circus career after being badly mauled by a bear. She married Gregory Bern, an electrical engineer she had known in Russia. They settled in Los Angeles, but were divorced in 1946. According to Maria, Bern had called her bad names, struck her, and finally left. “He just deserted me, that’s all,” she told the judge.

After her divorce, Maria moved to a comfortable duplex in Silverlake, a neighborhood in Los Angeles with a large Russian population. After decades on the run, she had finally found the home where she would live out the rest of her long life. Ever the adaptive survivor, she went to work as a machinist at the shipyards in San Pedro. “Lathe, drill press–I operate them all,” she explained. “You name it, I do it.”

Maria Rasputin being interviewed by a journalist from the Spanish magazine Estampa in 1930. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

During the Red Scare, Maria was ironically rumored to be a communist, leading her to write a strongly worded letter to the Los Angeles Times in 1948:

I am constantly being persecuted and branded a communist due to my name being Maria Rasputin, daughter of Gregory Rasputin, known as the “Mad Monk of Russia.” I left Russia 28 years ago and am now a naturalized American citizen, for which privilege I thank God every night, as I love the United States of America from the bottom of my heat. I wish to announce publically that I am not a communist even though my name is Maria Rasputin, daughter of Gregory Rasputin.

After retiring from the shipyards, Maria continued to support herself with social security payments and gigs as a babysitter and caregiver. Known to many as a friendly, amiable lady, she lived a quiet, secluded life, faithfully attending the neighborhood Russian Orthodox Church almost every week. She would give interviews when she needed money, her story often changing depending on who was interviewing her. She briefly believed that Anna Anderson, an impostor who claimed to be the murdered Grand Duchess Anastasia, was telling the truth, but later retracted her support. Throughout her interviews one thing remained constant. She never wavered from the belief that her father was a good, kindly man, who had been vilified by a manipulative society that he was too simple to understand.

In 1977, she published her final book, Rasputin: The Man Behind the Myth. Co-authored by journalist Patte Barham, it thrust Maria once again into the spotlight. She died shortly thereafter, on September 27, 1977, in her quiet duplex in Silverlake, and was buried in the nearby Angelus Rosedale Cemetery. On the cusp of her 70th birthday, she told a reporter for the Los Angeles Times: “I have a very exciting life.” In Maria Rasputin’s case, at least, this was quite an understatement.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook