How Man-Midwives Armed With Rusty Forceps Shook Up Obstetrics

Men in the delivery room were not well received.

A male midwife does a hands-on exam of a pregnant woman as her irritated husband looks on. (Cropped image: Wellcome Library/CC BY 4.0)

Today’s privileged pregnant woman has a lot of tough choices to make when considering her labor and delivery. Epidural? Doula? Playlist?

In 18th-century London, well-off women hoping to have a baby without incident faced a simpler, but starker question: was it indecent to give birth with the assistance of a man-midwife?

Dr. William Smellie, king of the “man-midwives,” as males in the profession were termed, was at the center of a huge shake-up in childbirth that saw women displaced from the delivery room as men armed with forceps greased with pig fat muscled in on the business of birth.

A cartoon of the man-midwife, a curious creature indeed. (Image: Wellcome Library, London/CC BY 4.0)

Nowhere was this shift more evident than in the classified pages of London’s Daily Advertiser on October 28, 1742. Right beside a notice of a lost silver watch and an announcement of the upcoming Annual Feast of the Gentlemen was a curious advertisement. Smellie, it read, was beginning “a course of lectures” on midwifery, for men.

During these lectures, the ad promised, “all the several Branches of that Art will be fully and clearly explain’d, and the whole illustrated with proper Machines, so contrived as to represent real Women and Children.” Though the initial informational lecture at his home would be free, William Smellie’s pupils would thereafter, “on reasonable Terms, have the Opportunity of attending Women in Time of Labour, and at their Delivery.”

Prior to the 17th century, the birthing process was an all-woman affair. Babies arrived to rooms full of female friends, family members, and a midwife. Men, even husbands and doctors, were not allowed to be part of the proceedings. Any breaches of this rule were dealt with severely—the Journal of Medicine and Science notes that “Dr. Wertt of Hamburg, in 1522, put on a woman’s dress to attend and study a case of labor, and was burned alive for his pains.”

The old way of giving birth: three women, two chairs, and no tools. (Image: Public Domain)

In a natural birth with no complications, the midwife’s duty, according to a 17th-century midwifery handbook, was “to attend, and wait on, nature, and to receive the child; and (if need require) to help to fetch the after-birth.” There were no tools involved, and mid-wives were encouraged to take their time. “When the child’s head doth offer itself, the midwife must gently receive it with both her hands,” the handbook said, before warning that the baby “must not bee pulled forth hastily, or rashly from the woman’s body.”

Men were only allowed in when things went wrong. In the unfortunate case of a stillbirth, a male physician would be called in to extract the infant’s body from the mother using fearsome-looking, hook-shaped instruments. This extraction method was also the frequent outcome of obstructed labor cases such as breech births, in which a living baby would present feet-first or bottom-first.

At the time, rickets was running rampant among English women, weakening bones and causing pelvic deformities that could make labor more difficult. In many instances, babies were essentially stuck in their mother’s uterus. To pull them out often meant sacrificing the life of the child, the woman, or both.

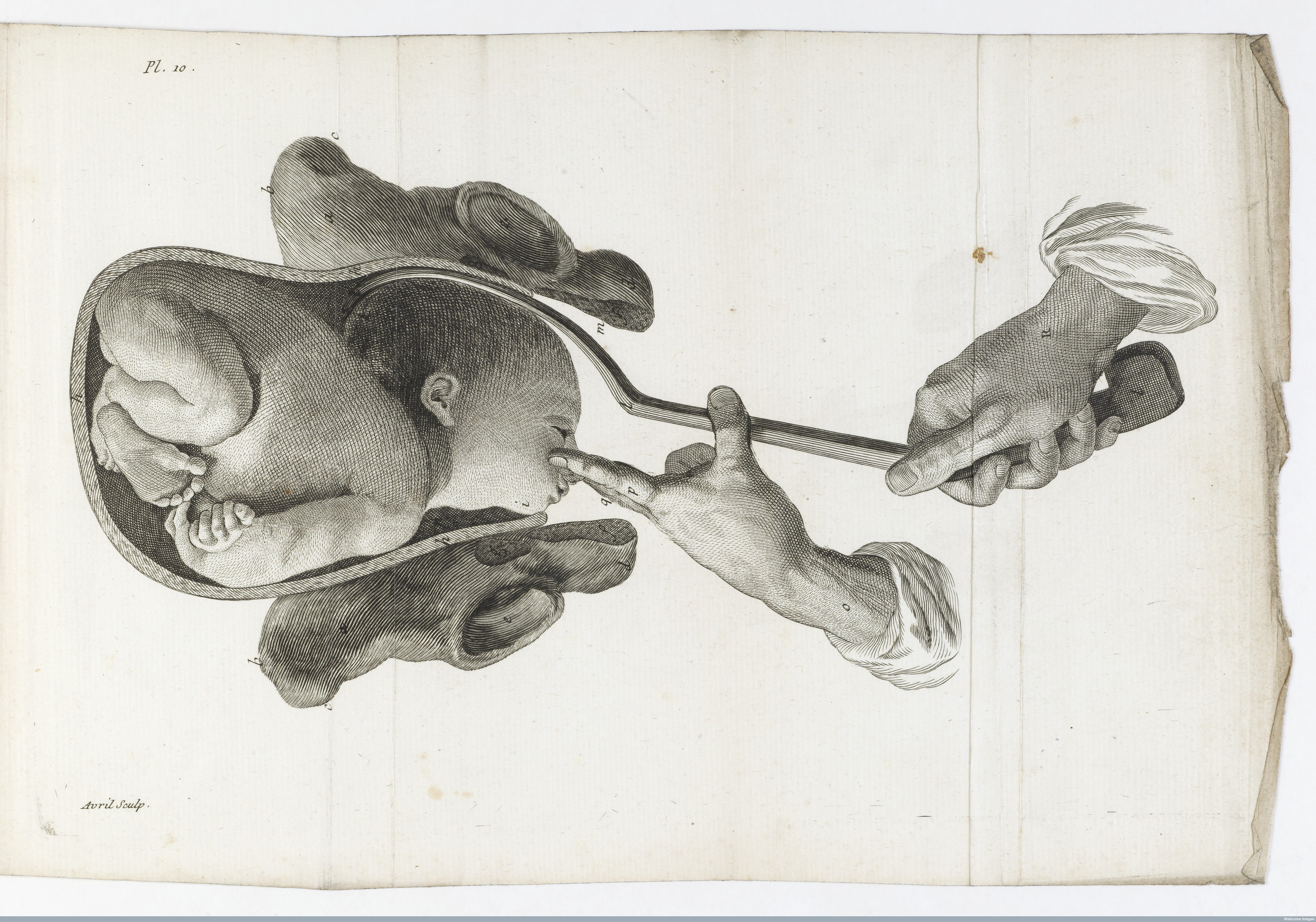

In the 17th century, babies were extracted with hook-shaped tools that could cause mortal damage. (Image: Wellcome Library, London/CC BY 4.0)

Then came the Chamberlens. At the dawn of the 17th century, the Chamberlen family, a French Huguenot clan whose male members were, unusually, involved in midwifery, fled to England to escape religious persecution in France. In their new home, they soon garnered a reputation for being the best midwives in the business. When faced with obstructed-labor births, they managed to keep both mother and child alive. Kings summoned them to attend their pregnant queens and deliver future monarchs, like Charles II.

Much of the Chamberlens’ success was due to an instrument of their own invention: the obstetric forceps. These tong-like tools, designed to grasp the head of a baby and bring it into the world with force and haste, were revolutionary. The Chamberlens went to great lengths to keep them a trade secret.

At births in the mid-17th century, Peter Chamberlen, the most prominent man-midwife of the family, would blindfold the laboring mother so she couldn’t see him taking his forceps out of their special gilded wooden box. The delivery room would also be locked so family members didn’t get the opportunity to learn about the intimidating tools that kept the Chamberlens in such high demand.

Though English physicians gradually wised up to the presence of forceps in their midst, it wasn’t until 1733 that the instruments officially became public knowledge. That year, surgeon Edmund Chapman published his “Essay for the Improvement of Midwifery,” which included a description of the tools the Chamberlens had been using, and the variants established since.

Obstetric instruments, including hooks, crotchets, and two pairs of forceps in the center. (Photo: Science Museum, London/CC BY 4.0)

The forceps were responsible for a radical shift in the nature of labor—one that involved women being displaced as the rulers of the birthing process. Midwives were not trusted to use forceps, as they were not considered strong or skilled enough to handle them. As a result, the standard operating procedure—which featured a midwife in charge, with a male surgeon or man-midwife only being summoned in the case of a stillbirth or breech—began to change.

Men would be booked ahead for a birth, initially in anticipation of a difficult labor, and later for general peace of mind. Instead of functioning as an adjunct to the midwife, the male surgeon—or man-midwife, for the two were becoming conflated—now ruled the room.

Midwives and many doctors were less than thrilled by this development. In her 1760 Treatise on the Art of Midwifery, veteran practitioner Elizabeth Nihell tore into man-midwives, accusing them of indecency, lack of respect for female modesty, and cursing the “natural impatience” that compelled men to use “those infernal iron and steel instruments” to unnaturally hasten a delivery.

A man-midwife delivers a child to a mother and two seemingly exasperated women. (Cropped image: Wellcome Library/CC BY 4.0)

Nihell was also aghast at a mechanical device Smellie had built to demonstrate birth to his students:

“a wooden statue, representing a woman with child, whose belly was of leather, in which a bladder full, perhaps, of small beer, represented the uterus. This bladder was stopped with a cork, to which was fasted a string of packthread to tap it, occasionally, and demonstrate in a palpable manner the flowing of the red-colored waters.”

Such a thing could not effectively prepare trainee man-midwives for the realities of birth, Nihell argued, but men practicing on live women was obscene.

A wooden obstetric teaching device similar to those used by Dr .Smellie in the 18th century. (Photo: Wellcome Images/CC BY 4.0)

Even Smellie’s seemingly beneficial modified forceps design, which featured a shorter handle and a layer of leather covering the metal tongs, caused problems. The leather, coated in hog’s lard for easier insertion, was intended to provide a softer surface for the baby’s head and guard against injury to the child and mother.

It being the pre-sterilization era, Smellie encouraged his practitioners to change the leather in between each patient in order to prevent the spread of venereal disease. But in practice, this didn’t happen, and many women developed septicemia as a result of the germ-infested forceps being used on them.

A pair of Smellie’s forceps. The right tong has retained its leather coating. (Photo: Science Museum, London/CC BY 4.0)

In the opinion of a few vocal professionals, these women brought such maladies on themselves by immodestly allowing man-midwives to treat them. In his 1793 collection of letters, Man-Midwifery Dissected, former midwifery student John Blunt said women who permitted men to deliver their babies were “female brutes” who “have stoically forgotten to blush, unless it be by the assistance of rouge.”

With the dawn of the morally rigorous Victorian era, the outrage against man-midwives focused less on forceps and more on on the impropriety of exposing pregnant women to young, lascivious men—in Man-Midwifery Exposed, Dr. John Stevens referred to man-midwives as “a deep, silent, secret source of adultery and cruelty … well-dressed vice, fawning to the heart’s best affections, like the reptile in the garden of Eden.”

Eventually, concern over man-midwives and their brutish forceps became less relevant as sterilization practices, caesarian deliveries, and vacuum extraction took hold. Male doctors came to be accepted as a standard presence in the birthing room, but male midwives still tend to encounter suspicion from expectant mothers and female colleagues. A 2014 report found that there were 103 men working in the field in the U.K., compared to 31,189 women.

Man-midwives may have been a major part of the obstetric revolution, but women are back in charge of birth.

Update (6/30): The story originally stated that the Chamberlen family fled the Huguenots—the Chamberlens themselves were Huguenots.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook